You will need Python 3 Anaconda Distribution and Tweepy installed to run project code.

3. Data Acquisition and Description

5. Naive Bayes and Logistic Regression

Stylometry is the process of attributing authorship through unique writing styles. Specifically, it attempts to identify writer invariants - characteristics of author passages both unique to the same author and persistent throughout author passages. This project will apply such techniques to the analysis of raw Twitter data to explore their feasability given Twitter's 140-character limit per post.

My aim is to limit myself to techniques that anyone who has worked with the the iris classification problem can understand. This is because some of the prospective users of my final result want to know for themselves how stylometry works in practice, and these people found a well-known set of tools in this area (Jstylo and Anonymouth) to not be user-friendly for laypersons.

Adhering to their value of "don't trust what you can't understand," the executible result will show how two twitter feeds can be "fingerprinted" in a manner that allows attribution of unnamed tweets from either user to take place. Over time I plan to continue expanding the proof of concept to work with a wider variety of feeds as well as additional machine learning techniques.

As successful methods for "fingerprinting" feeds are found, adversarial techniques for obfuscating writing styles will be explored as well. My aim is to develop a relatively easy process for protecting the pseudonymity of individuals on social media, as well as demonstrate that character limits on posts do not prevent unique posting styles from surfacing.

This project can be thought of as a more sophisticated version of what many consider to be the "Hello world" of machine learning: The Iris classification problem. Rather than classifying four existing measurement features (length/width measurements of *sepals and petals) under three categorical outcomes, this project will entail the use of over a dozen features to attribute tweets between two categorical outcomes. From start to finish, it will boil down to the following:

- Utilizing Twitter's API to acquire user tweets in CSV form

- Write code blocks for each of the tweet features being measured

- Pre-process (fingerprint) users so classification can be applied

- Apply classification algorithms to build authorship attribution model

- If possible, develop methods for subverting those classification schemes

The outcome of this project will be a tradeoff between accuracy and simplicity. Pre-processing will be used to "fingerprint" feeds, then supervised learning in the form of linear discriminant analysis will be used to attribute authorship. As requested by a prospective user of the final code result, this project will account for the fact that many people would rather use something they can understand than something that "claims" to be most effective.

In the absence of usernames, what features can we best identify tweet authorship with that are statistically unique as well as consistent throughout an author's writing? It appears such features can largely be classified under the following categories:

- Numeric: Average sentence length, syllables per word or tweet, characters per tweet, etc.

- Synonyms: Word choice, contraction use, abbreviations, internet slang, etc.

- Punctuation: Choice between comma, semicolon, or hyphen use, among other things.

My hypothesis is that despite the fact that Twitter comments ('tweets') are limited to 140 characters, there are features that are unique to tweets which would enable them to be easily attributable in a non-adversarial setting (no conscious attempt to obfuscate 'tweet' style by authors). These features include, but are not limited to:

- The use of hashtags in twitter comments.

- How often a user replies to others.

- The frequency at which a user links to other sites.

- A user's choice and frequency of emoji usage.

Placing a very short character limit on any social media posts may force users to develop unique ways of making text more succinct (such as abbreviations or chat slang). With pure stylometry, an effective scheme for authorship attribution is able to achieve it's goal without relying on choice of subject matter. Posts with 140 characters or less should still develop writer invariants that can be detected through pre-processing methods discussed later in this paper. Though enhanced techniques for identifying authors might be possible using various forms of topic modeling, those are (for now) beyond the scope of this project. I will limit my focus to features that are independent of whatever topic is being discussed.

Summary: For now, I have chosen to use two Twitter feeds (DLin71 and NinjaEconomics) for demonstration purposes.

According to research done by Drexel University Researchers who applied stylometry techniques to more open-ended text passages (namely internet black market communications), the accuracy of a classifier does not improve much after five thousand words from a given author have been used to train the model.

I am limiting myself to two feeds that are focused on the same subject matter, thus reducing the possibility that the final model reliability stems from differences in what two users are discussing (that would not be true stylometry). Prospective users of the final code result have insisted I start with something they could understand rather than focus on high accuracy.

Previously I utilized Twitter's API using Twython in a code editor, but this lacked the functionality I was looking for:

def __main__():

from twython import Twython

print 'test'

twitter = Twython("") # I removed my access tokens from here for obvious reasons

from pprint import pprint

#pprint(twitter)

search_result = twitter.search(q = 'stylometry')

#pprint(search_result)

for status in search_result ['statuses']:

user = status['user']['screen_name'].encode('utf-8')

text = status['text'].encode('utf-8')

print user, ":", text

print

__main__()Instead, I found that the following Tweepy script served my needs quite well. I modified it so it only included timestamps for tweets as well as their raw text content.

import tweepy

import csv

import sys

#Twitter API credentials (I removed my access tokens here too)

consumer_key = ""

consumer_secret = ""

access_key = ""

access_secret = ""

def get_all_tweets(screen_name):

#Twitter only allows access to a users most recent 3240 tweets with this method

#authorize twitter, initialize tweepy

auth = tweepy.OAuthHandler(consumer_key, consumer_secret)

auth.set_access_token(access_key, access_secret)

api = tweepy.API(auth)

#initialize a list to hold all the tweepy Tweets

alltweets = []

#make initial request for most recent tweets (200 is the maximum allowed count)

new_tweets = api.user_timeline(screen_name = screen_name,count=200)

#save most recent tweets

alltweets.extend(new_tweets)

#save the id of the oldest tweet less one

oldest = alltweets[-1].id - 1

#keep grabbing tweets until there are no tweets left to grab

while len(new_tweets) > 0:

print "getting tweets before tweet ID %s" % (oldest)

#all subsiquent requests use the max_id param to prevent duplicates

new_tweets = api.user_timeline(screen_name = screen_name,count=200,max_id=oldest)

#save most recent tweets

alltweets.extend(new_tweets)

#update the id of the oldest tweet less one

oldest = alltweets[-1].id - 1

print "...%s tweets downloaded so far" % (len(alltweets))

#transform the tweepy tweets into a 2D array that will populate the csv

outtweets = [[tweet.created_at, tweet.text.encode("utf-8")] for tweet in alltweets]

#write the csv

with open('%s_tweets.csv' % screen_name, 'wb') as f:

writer = csv.writer(f)

writer.writerow(["Time and Date Tweeted","Raw Tweet Content"])

writer.writerows(outtweets)

pass

if __name__ == '__main__':

#pass in the username of the account you want to download

get_all_tweets("balajis") #Balajis is the first feed I ever tested the script on my own computer withThe pre-processing phase involves taking a CSV file for any given Twitter feed and extracting information about the raw content that will be useful for logistic regression. This can be thought of as the digital equivalent of Ronald Fisher making his Iris sample measurements for later classification. The next question at hand is deciding which features to include in the modeling process.

This is a sample of features which were considered due to the possible likelihood that they are both persistent and unique to any given Twitter feed:

- Average sentence length in words and characters

- Syllable count per word, sentence, and tweet

- Word choice frequency and contraction use

- Distribution of "stop" words (that have no special meaning)

- Average hashtags per tweet/which hashtags

- Use and frequency of emojis or "smiley" character sequences

- Frequency of replies to other users/which users

- Frequency of linking to other sites/which domains

- Absence or presence of text placed before or after links

- Whether or not the original title of an article is included

Other features worth considering that do not stem from text style may include:

- Distribution of original versus retweets in a given feed

- Time series analysis of when tweet activity occurs from a user

- Possibile topic modeling, though that wouldn't be "true" stylometry

Overall, all of the possible features can be measured in at least one of three ways: whether something exists in a feed, what variety, and how much. For instance, hashtags and emojis can be measured in all three manners (does a feed contain them, which ones, how often).

This means the question of whether or not statistically unique patterns in a feed exist will almost always be yes, but this still leaves the issue of whether particular traits persist throughout new tweets. Both traits are necessary in order for a measured feature to qualify as a writer invariant.

Possibly the biggest challenge is narrowing down the list of chosen features so as not to get bogged down with the testing process. In my final demo, I decided to rely on the average number per tweet of the following:

- Syllables

- Periods

- Hyphens

- Commas

- Semicolons

- Exclamation marks

- Question marks

- Quotation marks

- Dollar signs

- Percentage symbols

- "&" symbols

- Asterisks

- Plus signs

- Equal signs

- Slash marks

These were selected because the frequency of use for any of these in a tweet by a user is more likely to persist regardless of the topic being discussed. They work well for demonstration purposes, especially if the aim is to use code someone new to python may want to modify for their own uses.

z = 0

total = 0

periods = []

for index, row in df.iterrows():

tweet = str(row['raw_text'])

z = z + 1

total = total + tweet.count('.')

print

print z, tweet.count('.'), total

period_count = tweet.count('.')

period_count = int(period_count)

periods.append(period_count)

df['periods'] = periods

# this gives us our final metrics

z = int(z)

average_period = total / z

total_period = total

print

print

print "Average period count: ", average_period

print

print "Total period count: ", total_periodIn a nutshell, the script above will go over every piece of 'raw text' in a row (that is, every tweet in a CSV file) and count how often a period is present. It also counts each time it goes over a new row so by the time it completes, it has a count of both the total number of periods as well as the total number of tweets in the CSV file. Both those figures are then used to find the average for any given tweet.

There are several potential features that are especially unique to tweets that could serve predictive power:

- The hash symbol (#), which is used to make a tweet present under certain "hashtags"

- The "at" symbol (@), which is placed before the name of another Twitter user if someone is trying to message ("tweet") them

- For CSV files generated by the Tweepy script above, "RT" indicates that the content of that tweet came from someone else. How often someone decides to "retweet" other people count turn out to be predictive of who they are.

- "http" in the raw text of a tweet is almost certainly an indication that they have linked to something. How often a user choses to do this may allow some level of attribution.

Because of the nearly limitless ways of deciding what characters to look for, and how to measure them (Median per tweet? Average in a week of activity? The possibilities are potentially infinite.), I chose to keep it simple and stick with the average occurance per tweet for the features I mentioned above. How I might approach this differently in the future is anyone's guess.

Two models were put to the test in attributing tweets from one user versus the other. Both have relative pros and cons which are described here.

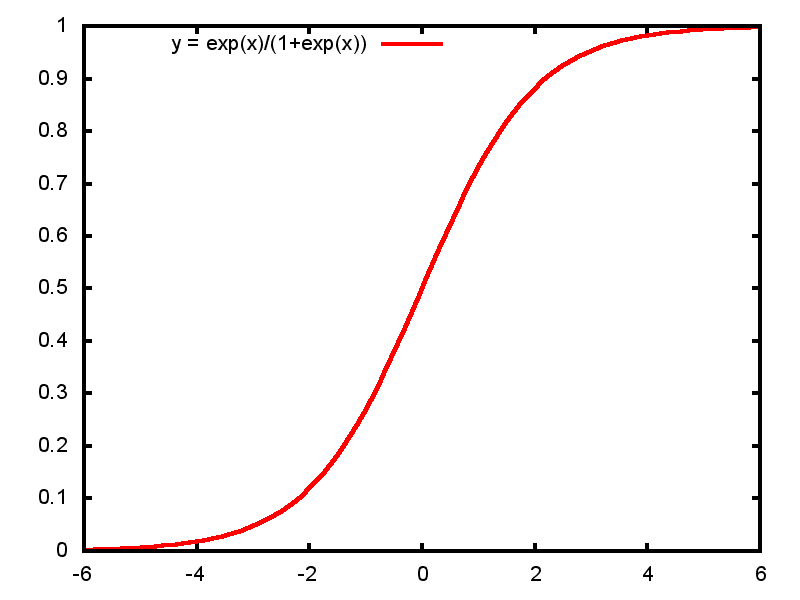

Logistic regression is a model used when the dependent feature y is categorical rather than continuous. In the case of this project, we are trying to see if any given tweet belongs to one user versus another. Below is a visual example of how it works in practice.

First, the logistic regression model is trained with a sample of tweets from both users in question. The more distinct they are from each other, the more horizontal and relatively flat the graph would be. However, if the two users have very similar styles of tweets, the opposite will be the case, and narrower range that results will be poorer at distinguishing the two.

The more similar a given tweet is to one user versus the other, the further to the left or right it will be categorized on the chart. Ideally we want the users to be different enough so the sigmoid is less narrow. That kind of distribution is less likely to lead to logistic regression wrongfully attributing a given tweet to one user versus another.

Naive Bayes on the other hand is a model that works more similarly to how spam filters work. It operates on conditional probability; that is, the probability that B will happen given that A occured. In the case of this project, the goal is to determine who made a tweet given that the word frequency of that tweet.

For this to be implemented in the Jupyter notebook used, there wasn't a need for as much preprocessing of the tweets. All that was needed was to convert the tweets into document-term matrices within the notebook. These are frequency distributions of terms that appear which are analogous to "statistical fingerprints" of the users being compared.

Finding an easy means of using Twitter's API to export tweets in CSV form took up the most time early on, but the modified Tweepy script above proved sufficient. From there the next challenge was writing code blocks for each prospective feature listed above, and finding a way of successfully looping them over each tweet in any analyzed feed. Here the goal was to pre-process the CSV files of each Twitter feed to obtain numeric figures.

In the end, all it took was a list comprehension function that iterated over every row to count how often a character appeared, and append that row with a new column containing the figure for that count. The code for this is in section four above.

The resulting CSV file from the pre-processing was unnecessary when using multinomial naive bayes. For pre-processing, all that was needed was to convert the tweets into document-term matrices, which were then used to distinguish the two feeds just from word frequencies alone.

This may be the main difference between how logistic regression and naive bayes was used in this project; the former was used to zero in on specific characters while the latter looked at word frequencies.

This will now conclude with a summary of the results, as well as further information for those who wish to either use this project or adapt/improve upon it in some way. Readers who skip to this section can still get useful takeaways about the project - I refer to the rest of the paper when relevant.

Before this began, it had been asserted to me by a handful of privacy-minded friends (on Freenet of all places, where people should know better) that public "microblogs" are safe from being "fingerprinted" for writer invariants. That is, because Twitter has a 140-character limit per post there is a lesser chance of detectable writing styles forming.

This turned out to be dead wrong. What actually takes place on Twitter is the use of slang, abbreviations, emojis, and other post habits that try to make the most of those character limits. In theory, any social media platform that imposes character limits on posts could lead to more detectable writer invariants forming for the same reasons.

The same rules about adversarial stylometry apply to Twitter. Obfuscation of write-prints must be done to reduce authorship attribution, but a special edge applies to anyone wishing to conceal their writing style. Generating a write-print and concealing it is easier to do for one person than generating a write-print for multiple individuals and attributing authorship to one of them.