The diffusion paradigm was developed by Ryan and Gross (1943), two rural sociologists who studied the diffusion of hybrid corn seed in two Iowa communities. The new hybrid corn, introduced in 1928, increased production by 20% and was more drought-resistant. However, farmers needed to purchase new seeds each year, instead of self-selecting seeds from their own plants. The new technology, therefore, led to important changes for the farmers. By surveying more than 300 farmers in 2 communities during 1941, Ryan and Gross showed that diffusion is a social process that spreads adoption in the community through subjective evaluation, rather than individual rational choice.

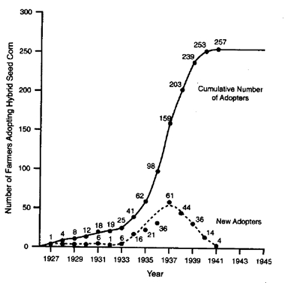

Diffusion processes often replicate the observed stylized fact of a S-shaped curve of cumulated adopters of the innovation (Figure 3). In fact, the increasing number of adopters is, in essence, the diffusion process. The adoption of new products is a complex process that typically consists of a large body of agents interacting with each other over a long period of time. Traditional analytical models described diffusion processes on the market level, since available data is often aggregated without attention to spatial distribution or individual characteristics. When individual data is available, these are snap shots of adopters’ surveys.

*

Figure 3. Diffusion of hybrid corn in two communities of Iowa (source: Ryan and Gross, 1943).*

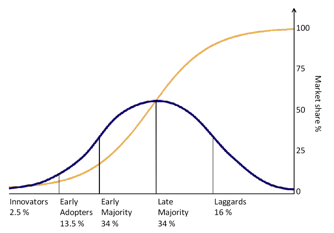

Diffusion processes have been studied in many disciplines such as anthropology, marketing, rural sociology and communications science. Everett Rogers (1962) synthesized the work of many studies and developed a framework of typical successful innovations. The initial adoption of an innovation is made by innovators, then early adopters, early majority, late majority and finally laggards may adopt the innovation too (Figure 4).

As we develop a model of the diffusion of innovation, we need to take into account that there is variability within the population when adopting something new (i.e., innovators versus laggards). Furthermore, there is likely to be interaction among agents that leads agents to imitate or copy the behavior of innovators. The position of the innovator within a social network may affect the diffusion pattern.

*

Figure 4. Diffusion of innovations. With successive groups of consumers adopting the new technology (shown in blue), its accumulative total (yellow).*

Although empirical investigation of dynamic micro level processes is limited and difficult to accomplish, computational models have been developed which can be used to investigate the consequences of different assumptions of agents on the diffusion of an innovation.

The traditional model on the aggregate penetration of new products is the Bass model (1969) which follows Rogers’ diffusion of innovation (Rogers, 1962). The Bass model emphasizes the role of communication, namely external influence via advertising and mass media, and internal influence via word of mouth. The decision of an individual is described as a probability of adopting a new product at time t, which is assumed to depend linearly on two forces. The first force is not related to previous adopters and represents the external influence, and the other force represents the internal influence and is related to the number of adopters.

dN(t)/dt=p[m-N(t)]+q/m N(t)[m-N(t)]

where N(t) is the cumulated number of adopters at time t, m is the potential number of adopters, p reflects the influence that is independent of previous adoption, and q reflects the influence due to word of mouth. Although the Bass models fits very well with much of the data, its relevance to real consumer behavior is questioned. One of the problems is that the model only explains an observed successful diffusion process, and cannot predict whether a new product will be a success or a failure.

One way to simulate the diffusion process from an agent-based perspective, is to equip the agents with thresholds when to adopt an innovation. For example, Mark Granovetter (1978) presented a framework which assumed that thresholds to join a collective behavior differ among individuals, and that the type of distribution affects the macro-dynamics of the system. Granovetter (1978) focused on processes in which adoption could be monitored by the whole group. More relevant for many diffusion processes, is to base the threshold model on personal networks. Valente (1995) analyzes in detail threshold models for a number of data sets. Thresholds in his models are based on the individual personal network. An interesting finding is that less risky innovations spreads faster if the central connected agents have a low threshold for adoption. For more risky innovations, individuals who are less connected adopt the product first, which may reduce uncertainties and lead to diffusion to the whole group afterwards.