Sorting Through the Layer Interactions

With the introduction of Linux and Containers to the App Service capabilities, the world of PaaS container hosting gets a little more palatable for those that are looking to modernize the application deployment footprints, but do not want to take on learning all of the intricacies of a running a full environment using something like Kubernetes. With containers on App Service we can reap the benefits of containerized deployments in addition to the benefits of the high-fidelity service integration that App Service has across the Azure services such as Azure Active Directory, Azure Container Registry, App Insights, and so on.

However, with a new system comes new things to understand in order to get the most out of the system. In this writing, I will focus on key considerations for scaling when hosting a containerized Python application using App Service. This is a key consideration as we move from the IIS + FastCGI world into the Linux + NGINX + uWSGI world in App Service.

I want to cover a little background on the tools used and the structure of the application. For those familiar with FastCGI, but not with uWSGI it is easiest to think of it as a superset replacement for the CGI capabilities provided by FastCGI. uWSGI can be used as a stand-alone server and to that end is a little more like IIS + FastCGI. In practice, uWSGI is commonly used with something like NGINX which serves as the front-line middleware server handling the web traffic and passing the requests back to uWSGI based on configuration.

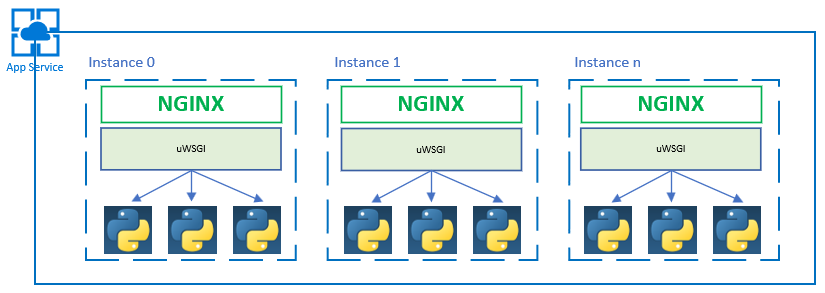

The container I'm using will be running NGINX + uWSGI + Python for each instance running in App Service. In Kubernetes, a single node may run one or more pods each running one or more containers. In App Service a node, or instance in App Service terms, will host only a single running container. Thus, the App Service container topology that I'm using will look more like that depicted in Figure 01 below.

Figure 01: App Service + Container Topology

As illustrated in Figure 01, each container hosts an NIGINX and an uWSGI process in addition to a configurable number of Python worker processes. My default setup will spawn no more than 2 Python worker processes. As one might imagine, this can leave me in a bit of a lurch when it comes to scaling my deployment. Depending on the rules I've setup for Autoscale and the execution profile of my application I may not be able to drive the metrics high enough to trigger the Autoscale action for App Service. Thus, I'm pinned at 1 instance + 2 workers in perpetuity. There's no magic here as I must put the effort into understanding the behavior of my app as it scales in order to determine which levers to adjust to get the infrastructure to behave as I desire. What is decidedly different are the levers. Instead of just VMs or even containers, we have a matrix of instance size, container, and worker processes. For example, some options are:

- run multiple uWSGI processes and have the NGINX workers balance across the uWSGI instances

- Ensure that my Python codebase is thread safe and use threads in uWSGI which in turn creates a new ThreadState for the existing interpreter

- Spawn multiple single threaded Python workers

This is the grey area in which experience and opinion have heavy sway on the direction one takes. In my setup, uWSGI's job is to primarily to broker requests to Python workers. Thus, my inclination is to rule out #1 as it adds a lot of overhead to scale out the processes doing the work. Using threads is a more common practice, but my inclination is that using ThreadState in Python apps serving web applications increases the difficulty of debugging. I'd rather avoid the being lead on a roundabout chase to pin down and resolve threading issues and GIL contention. Moreover, as a design I fear it will lead to leaky practices for sharing state information. My preference is more of shared-nothing model from the application code perspective. Of course, the application will have a shared infrastructure and compute footprint, but I'd rather not have the code dependent on an in-process shared memory state that I must protect and synchronize in my code. If I had a memory heavy caching application I might reconsider, but I'm targeting low to mid-level memory usage and mostly CPU constrained execution.

The test driver is pretty simple in that I convert an array of numbers to strings, hash the string value of each, and then sort the array. It is meant to take time and drive some amount of CPU usage. For each execution of the test it will generate an array of 10,000 numbers on which it will perform the previously described operations. I've created a route that will execute the test driver and do it for n times based on the value of loopCount which is passed as a query parameter. If no parameter is found then the default value of 10 is used. This is the URL that I will use to execute the test: https://py-simple-docker.azurewebsites.net/helloworld/?loopCount=20. As can be seen, I'm loop 20 times for each execution.

To run the test and drive concurrency, I'm using Apache Bench (ab) (https://httpd.apache.org/docs/2.4/programs/ab.html). I performed the test from my Windows 10 laptop using the Windows Subsystem for Linux. It was easy to install and run straight from there. Using ab makes it simple to run the same tests from various machines whether Windows, Mac, or Linux machines so it is good choice for flexibility and personal use. For all of my runs I'm using the following command with the only variance being concurrency:

ab -c [2, 4, 6] -n 200 https://[app name].azurewebsites.net/helloworld/?loopCount=20In the final two runs I use 1000 for the number of requests so that I may demonstrate Autoscale taking effect in App Service.

For each run, I'm changing the uWSGI cheaper (https://uwsgi-docs.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Cheaper.html) settings in the uwsgi.ini file. The cheaper subsystem controls the number and manner in which Python workers are spawned and killed. My final configuration looks like the following:

[uwsgi]

module=main

callable=app

buffer-size=16384

workers = 16 # maximum number of workers

cheaper-algo = spare

cheaper = 2 # tries to keep 8 idle workers

cheaper-initial = 2 # starts with minimal workers

cheaper-step = 2 # spawn at most 2 workers at once

cheaper-idle = 300 # cheap one worker per 5 minutes while idle

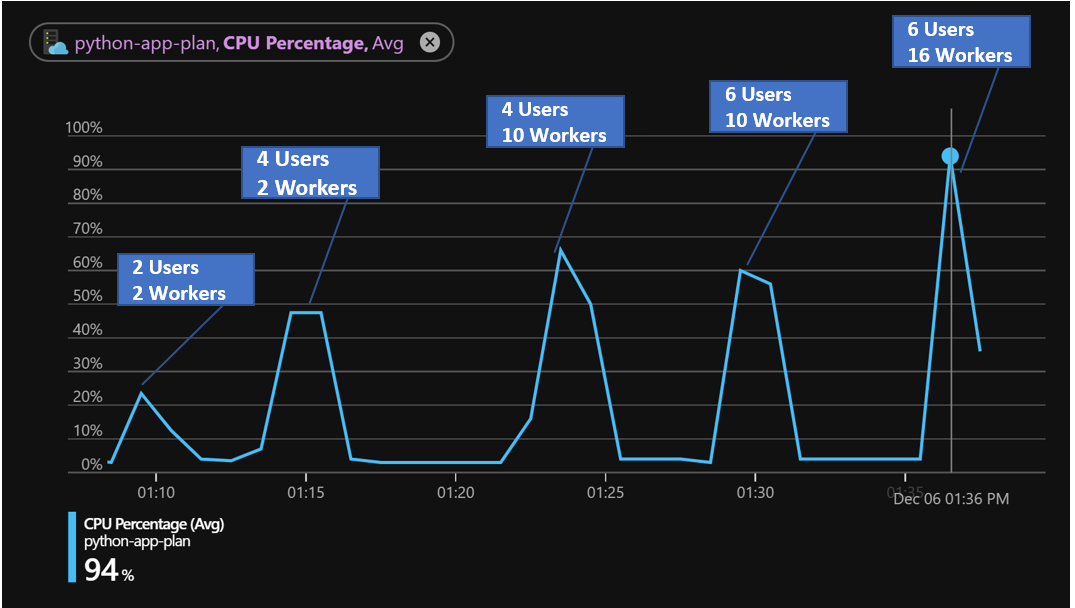

My initial test was with a static 2 workers, but the remainder of the tests I added cheaper settings to spawn workers based on my settings.

Figure 02: Single App Instance Tests with Increasing Worker Count

In combination with some of the figures captured in this matrix we can start to draw a little understanding of how the application behaves.

| Worker Max | Concurrent Users | Max Req Time(ms) | Max CPU % | Min Req Time(ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2 | 1983 | 49% | 1428 |

| 2 | 4 | 16469 | 47% | 1887 |

| 10 | 4 | 1818 | 66% | 1330 |

| 10 | 6 | 2834 | 60% | 2010 |

| 16 | 6 | 3147 | 94% | 2257 |

Figure 03: Single App Instance Test Data

Drawing from Figures 02 and 03, I can arrive at a couple of key assertions.

-

CPU utilization plateaus based on the number of workers. This means that for many of these test runs the infrastructure would not meet the Autoscale criteria for greater than 70% CPU utilization.

-

Increasing concurrency while holding the worker count steady means increasing request time as concurrent calls are serialized one behind the other and those beyond the worker process count must wait for a free process in order to be serviced.

The good news is that once I drive my workers to 16 the App Service instance is well over my 70% threshold for CPU utilization. All that's left now is to run it for a longer duration to see what that looks like for performance and then turn on autoscaling and rerun the same test.

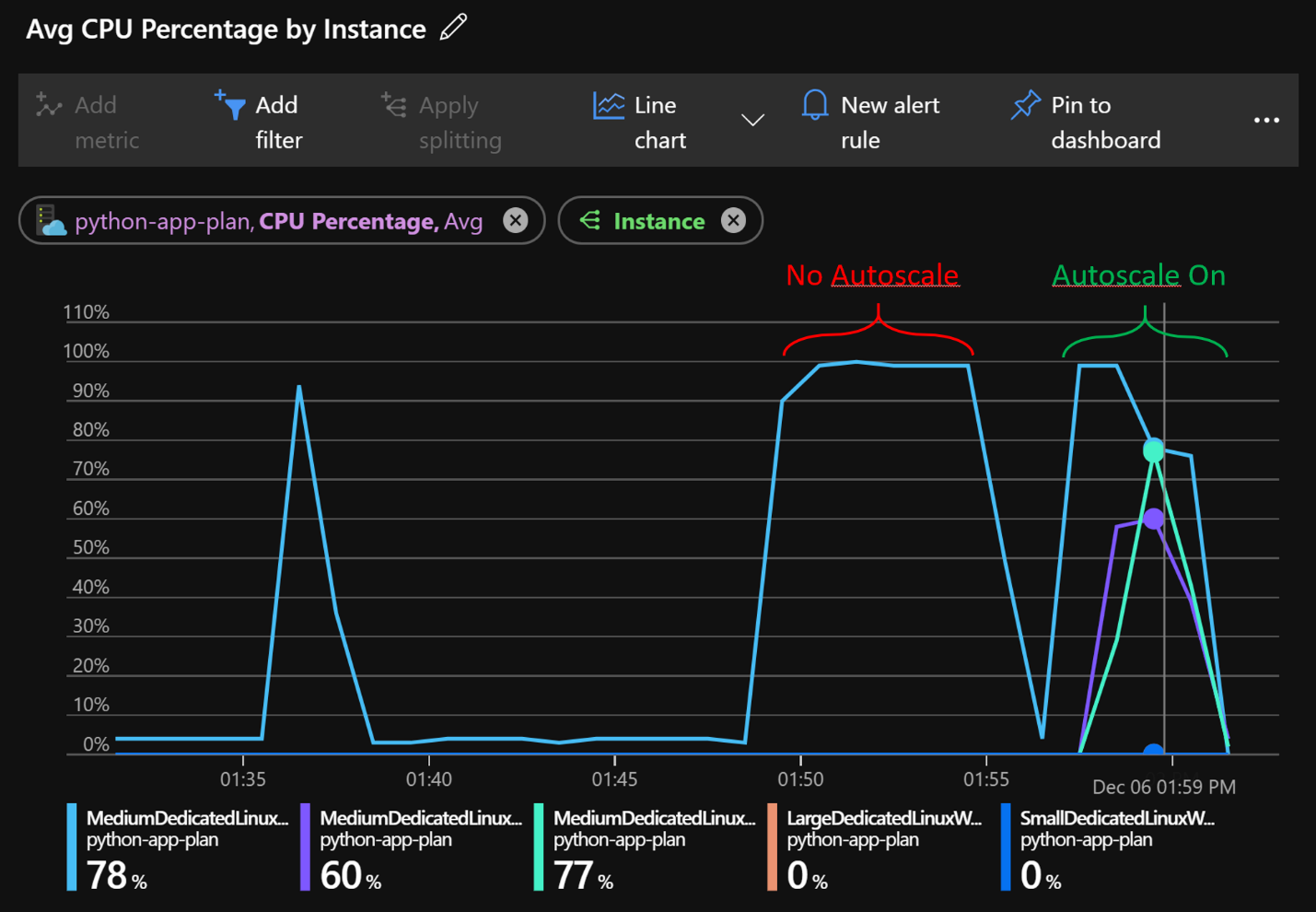

Figure 04: Longer Test Runs With and Without Autoscale

In Figure 04 the longer test runs can be seen. The No Autoscale run shows the CPU hitting 100% and maintaining that for the duration of the test. In the subsequent run what we see is the initial CPU hitting 100% and then App Service adding a couple of instances and the CPU lowering as the request load is spread across the instances. Additionally, the duration is visually shorter. In fact, the first run took 380 seconds while the second run for the same number of requests took 245 seconds. It follows that we should see shorter requests response times and more throughput.

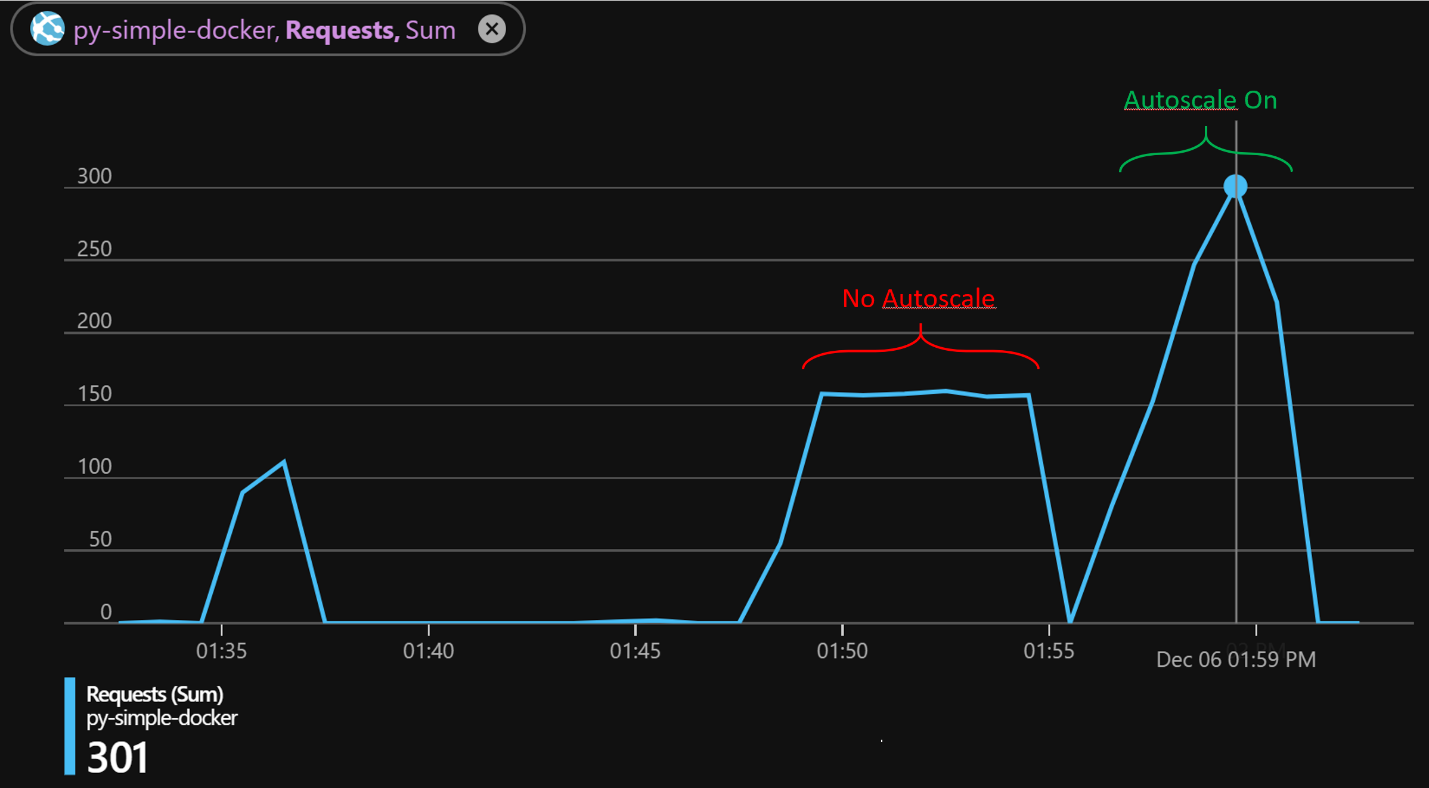

Figure 05: Throughput With and Without Autoscale

| Worker Max | Concurrent Users | Max Req Time(ms) | Max CPU % | Min Req Time(ms) | Autoscale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 6 | 21001 | 100% | 2270 | None |

| 16 | 6 | 3484 | 100% | 1160 | 3 |

Figure 06: Metrics With and Without Autoscale

In the run that is pushing the server without Autoscale enabled we see the response times drive up to 21s and the throughput top out around 150 requests. Once I turn on the Autoscale and re-run the test we see the max throughput nearly double during the duration of the test and the max request time drop back down to about 3.5 seconds. The delta between the max time and the min time for the requests is likely a combination of the response time as the initial instance plateaus while the other instances are brought online and just the amount of load that is being pushed. I imagine if I ran this for much longer the average would start to approach the minimum.

There is nothing new here. More processes and more CPUs handle more load and drive higher resource utilization. However, there is a bit of an inception obfuscation to sort through in order to answer questions such as:

- How do we scale?

- How can we ensure App Service autoscales as expected?

- Should we add it NGINX and uWSGI workers?

- How many Python workers are needed to drive the instance?

Most likely it is a combination of some or all of the elements indicated in the questions. To be prescriptive in the deployment configuration we have to tease apart the various components that drive load and must scale and come to an understanding of how they impact each other. For this example of a containerized Python application using uWSGI and running on App Service I've tried to illustrate how to configure the scale settings for the worker processes that in turn affect the scalability settings in App Service.

Lastly, the Dockerfile, uWSGI config, and the Python driver I used for this may all be found in this repo.