- In software engineering, a design pattern is a general repeatable solution to a commonly occurring problem in software design. A design pattern isn't a finished design that can be transformed directly into code. It is a description or template for how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations.

- Singleton

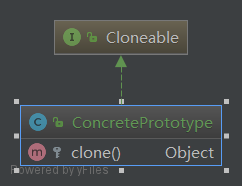

- Creationaldesignpattern.prototype

- Object Pool

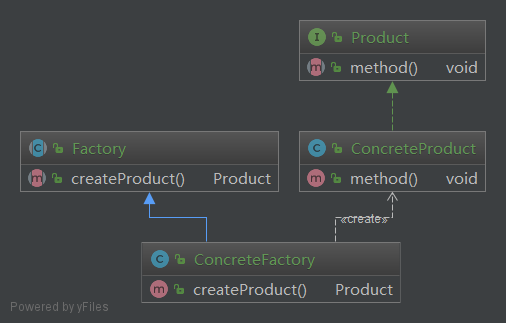

- Factory Method

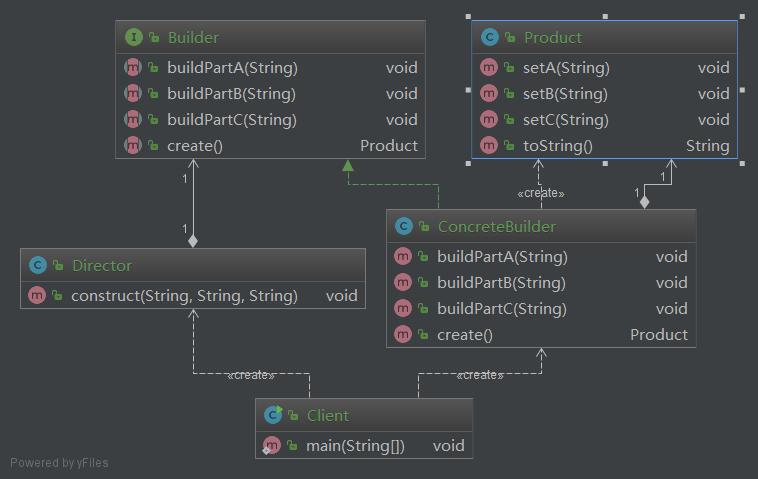

- Builder

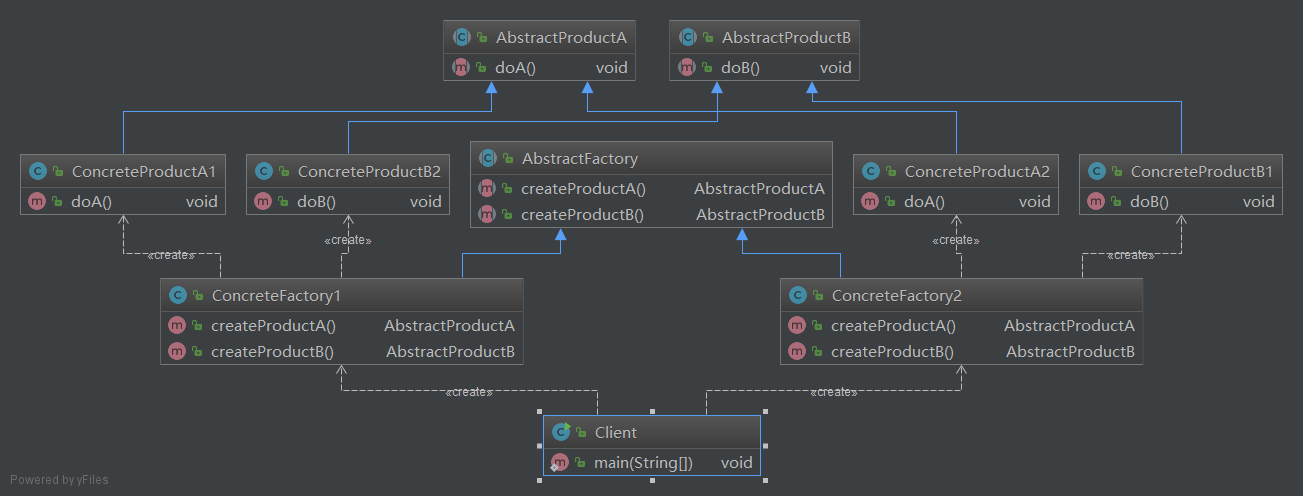

- Abstract Factory

- Adapter

- Bridge

- Composite

- Decorator

- Facade

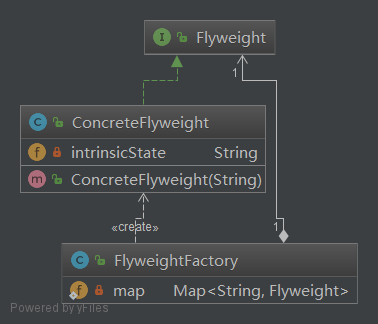

- Flyweight

- Private Class Data

- Proxy

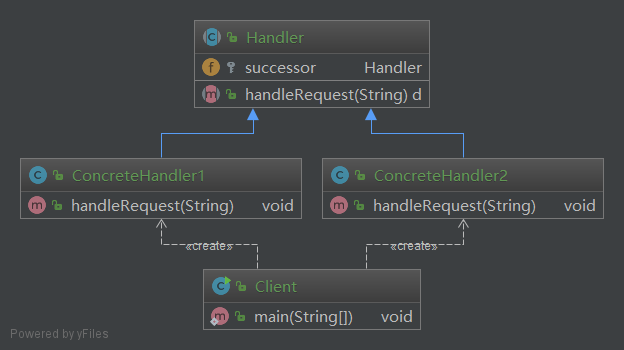

- Chain of responsibility

- Behavioraldesignpatterns.commandpatterns

- Interpreter

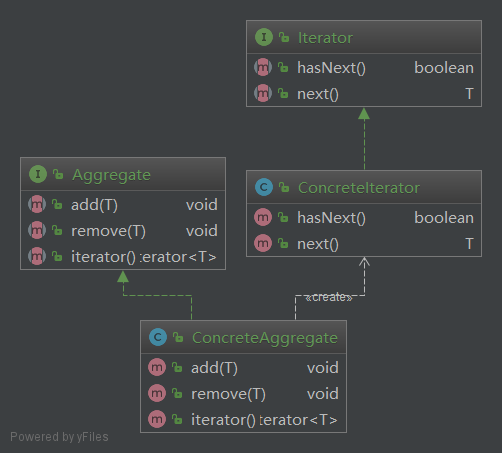

- Iterator

- Behavioraldesignpatterns.mediator

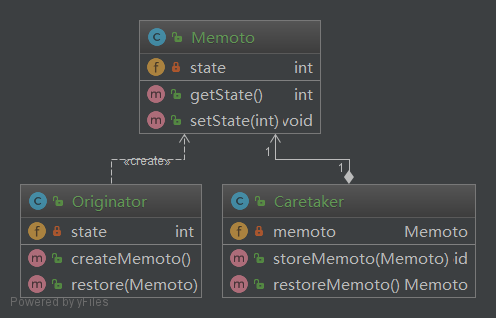

- Memento

- Null Object

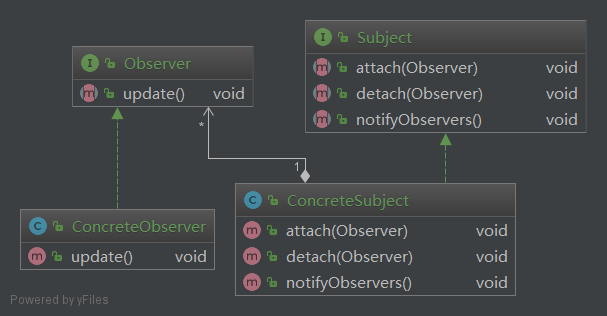

- Observer

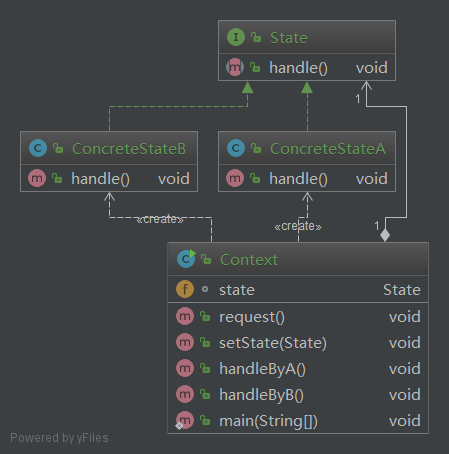

- State

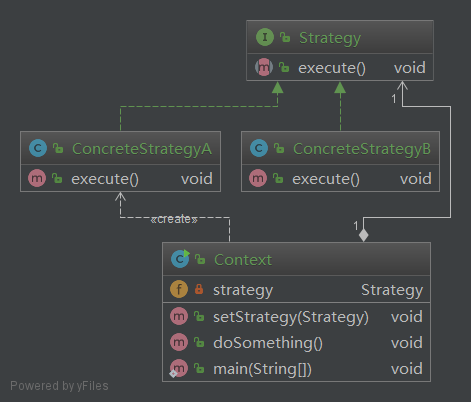

- Strategy

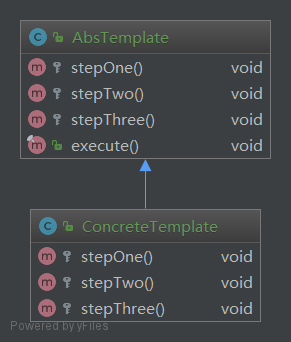

- Template method

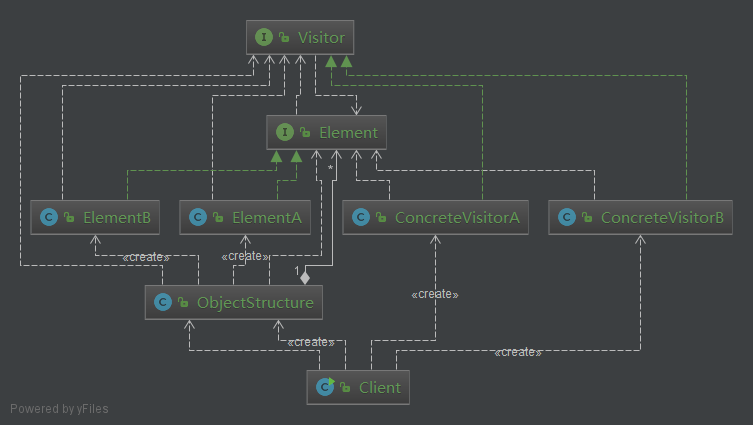

- Visitor

In software engineering, creational design patterns are design patterns that deal with object creation mechanisms, trying to create objects in a manner suitable to the situation. The basic form of object creation could result in design problems or added complexity to the design. Creational design patterns solve this problem by somehow controlling this object creation.

- Singleton

The singleton pattern ensures that only one object of a particular class is ever created. All further references to objects of the singleton class refer to the same underlying instance. There are very few applications, do not overuse this pattern!

class Counter private constructor() {

var count = 0

fun addOne() {

count++

}

object MySingleton {

val instance = Counter()

}

}val obj1 = Counter.MySingleton.instance

val obj2 = Counter.MySingleton.instance

obj1.addOne()

obj2.addOne()

println("Counter 1 : ${obj1.count}")

println("Counter 2 : ${obj2.count}")

obj1.addOne()

obj2.addOne()

println("Counter 1 : ${obj1.count}")

println("Counter 2 : ${obj2.count}")

println(obj1)

println(obj2)Counter 1 : 2

Counter 2 : 2

Counter 1 : 4

Counter 2 : 4

The Prototype pattern delegates the cloning process to the actual objects that are being cloned. The pattern declares a common interface for all objects that support cloning. This interface lets you clone an object without coupling your code to the class of that object. Usually, such an interface contains just a single clone method.

The implementation of the clone method is very similar in all classes. The method creates an object of the current class and carries over all of the field values of the old object into the new one. You can even copy private fields because most programming languages let objects access private fields of other objects that belong to the same class.

An object that supports cloning is called a prototype. When your objects have dozens of fields and hundreds of possible configurations, cloning them might serve as an alternative to subclassing.

import java.util.ArrayList

class WordDocument

constructor(var text: String = "", private var images: ArrayList<String> = ArrayList<String>()) : Cloneable {

init {

println("-----Init-----")

}

fun addImage(image: String) = images.add(image)

fun showDocument() {

println("-----Start-----")

println("Text: $text")

println("Images List: ")

images.map {

println("Image name: $it")

}

println("-----End-----")

}

fun cloneTo(): WordDocument? {

try {

val copy: WordDocument = super.clone() as WordDocument

copy.text = this.text

copy.images = this.images.clone() as ArrayList<String>

return copy

} catch (e: CloneNotSupportedException) {

e.printStackTrace()

}

return null

}

}fun main() {

val originDoc: WordDocument = WordDocument().apply {

text = "This is a document"

addImage("Image 1")

addImage("Image 2")

addImage("Image 3")

showDocument()

}

val copyDoc: WordDocument? = originDoc.cloneTo()?.apply {

showDocument()

text = "This is a copy document"

addImage("A new image")

showDocument()

}

copyDoc!!.showDocument()

}-----Init-----

-----Start-----

Text: This is a document

Images List:

Image name: Image 1

Image name: Image 2

Image name: Image 3

-----End-----

-----Start-----

Text: This is a document

Images List:

Image name: Image 1

Image name: Image 2

Image name: Image 3

-----End-----

-----Start-----

Text: This is a copy document

Images List:

Image name: Image 1

Image name: Image 2

Image name: Image 3

Image name: A new image

-----End-----

-----Start-----

Text: This is a copy document

Images List:

Image name: Image 1

Image name: Image 2

Image name: Image 3

Image name: A new image

-----End-----

The builder pattern is used to create complex objects with constituent parts that must be created in the same order or using a specific algorithm. An external class controls the construction algorithm.

data class Car

constructor(var color: String, var licensePlate: String, var brand: String) {

private constructor(Creationaldesignpattern.builder: Builder) : this(

Creationaldesignpattern.builder.color,

Creationaldesignpattern.builder.licensePlate,

Creationaldesignpattern.builder.brand

)

class Builder {

lateinit var color: String

lateinit var licensePlate: String

lateinit var brand: String

fun color(init: Builder.() -> String) = apply { color = init() }

fun licensePlate(init: Builder.() -> String) = apply { licensePlate = init() }

fun brand(init: Builder.() -> String) = apply { brand = init() }

}

companion object {

fun build(init: Builder.() -> Unit) = Car(Builder().apply(init))

}

} val car1 = Car.build {

brand = "Audi"

color = "Blue"

licensePlate = "C88888"

}

println(car1)Car(color=Blue, licensePlate=C88888, brand=Audi)

The Creationaldesignpattern.factory pattern is used to replace class constructors, abstracting the process of object generation so that the type of the object instantiated can be determined at run-time.

interface Cake {

fun prepareMaterials();

fun banking();

}

class MangoCake : Cake {

override fun prepareMaterials() {

println("prepare Mango Cream")

}

override fun banking() {

println("Baking ten minutes")

}

}

abstract class Factory {

abstract fun <T : Cake> createProduct(clz:Class<T>): T?

}

class CakeFactory : Factory() {

override fun <T : Cake> createProduct(clz: Class<T>): T? {

var cake: Cake? = null

try {

cake = Class.forName(clz.name).getDeclaredConstructor().newInstance() as Cake

}catch (e : Exception) {

e.printStackTrace()

}

return cake as T?

}

}

val Creationaldesignpattern.factory : Factory = CakeFactory()

val mangoCake = Creationaldesignpattern.factory.createProduct(MangoCake::class.java)?.apply {

prepareMaterials()

banking()

}prepare Mango Cream

Baking ten minutes

The abstract Creationaldesignpattern.factory pattern is used to provide a client with a set of related or dependant objects. The "family" of objects created by the Creationaldesignpattern.factory are determined at run-time.

abstract class CakeFactory {

abstract fun cream():CakeCream

abstract fun style():CakeStyle

}

abstract class CakeCream {

abstract fun cream()

}

abstract class CakeStyle {

abstract fun style()

}class HeartStyle:CakeStyle() {

override fun style() {

println("Heart Style")

}

}

class MangoCream:CakeCream() {

override fun cream() {

println("Mango Cream")

}

}class MangoHeartCake : CakeFactory(){

override fun cream(): CakeCream {

return MangoCream()

}

override fun style(): CakeStyle {

return HeartStyle()

}

}

val mangoHeartCake: CakeFactory = MangoHeartCake()

mangoHeartCake.cream().cream()

mangoHeartCake.style().style()

println("=================")

val mangoSquareCake: CakeFactory = MangoSquareCake()

mangoSquareCake.cream().cream()

mangoSquareCake.style().style()Mango Cream

Heart Style

=================

Mango Cream

Square Style

In software engineering, structural design patterns are design patterns that ease the design by identifying a simple way to realize relationships between entities.

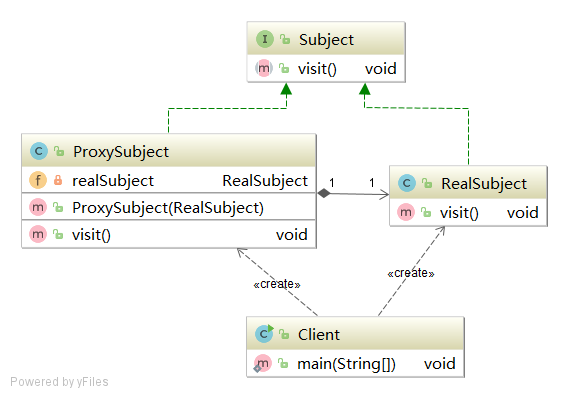

The proxy pattern is used to provide a surrogate or placeholder object, which references an underlying object. Protection proxy is restricting access.

interface IPicker {

fun receiveMessage()

fun takeCourier()

fun signatureAcceptance()

}

class RealPicker:IPicker {

override fun receiveMessage() {

println("Receive text Message")

}

override fun takeCourier() {

println("Take the Courier")

}

override fun signatureAcceptance() {

println("Signature Acceptance")

}

}

class ProxyPicker(private val picker: IPicker) : IPicker by picker

val picker:IPicker = RealPicker()

val proxyPicker = ProxyPicker(picker)

proxyPicker.receiveMessage()

proxyPicker.takeCourier()

proxyPicker.signatureAcceptance()Receive text Message

Take the Courier

Signature Acceptance

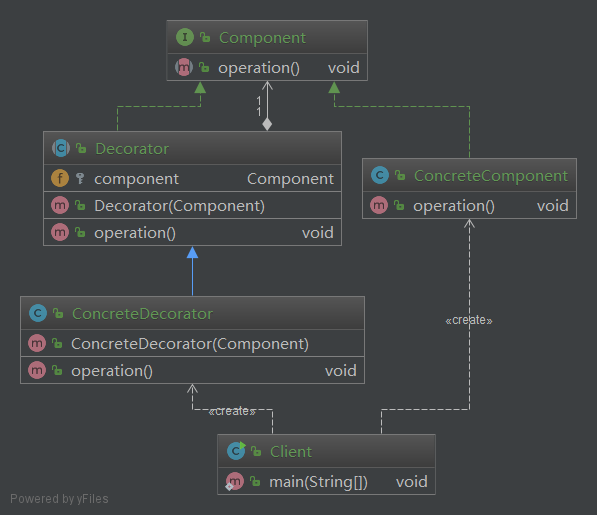

The decorator pattern is used to extend or alter the functionality of objects at run-time by wrapping them in an object of a decorator class. This provides a flexible alternative to using inheritance to modify behaviour.

interface Cake {

fun make()

}

class CakeEmbryo : Cake {

override fun make() {

println("Baking Cake")

}

}

open class DecoratorCake constructor(val cake : Cake): Cake by cake

class FruitCake constructor(cake:Cake) :DecoratorCake(cake) {

override fun make() {

addSomeFruit()

super.make()

}

private fun addSomeFruit() {

println("Add Some Fruit")

}

}

val cake: Cake = CakeEmbryo()

cake.make()

println("--------Decorate Fruit Cake--------")

val fruitCake: DecoratorCake = FruitCake(cake)

fruitCake.make()Baking Cake

--------Decorate Fruit Cake--------

Add Some fruit

Baking Cake

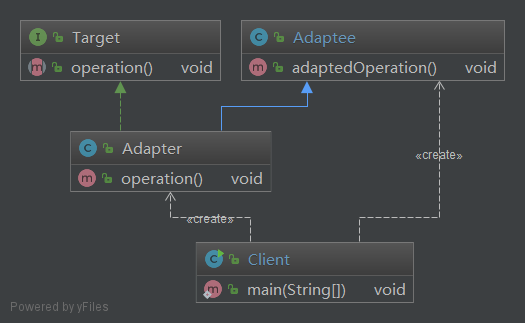

The adapter pattern is used to provide a link between two otherwise incompatible types by wrapping the "adaptee" with a class that supports the interface required by the client.

interface VoltFive {

fun provideVoltFive():Int

}

class Volt220 {

fun provideVolt220(): Int {

return 220

}

}

class VoltAdapter(private val volt220: Volt220) : VoltFive {

override fun provideVoltFive(): Int {

val volt = volt220.provideVolt220()

return 5

}

fun provideVolt220(): Int {

return volt220.provideVolt220()

}

}

val volt220 = Volt220()

val Structuraldesignpatterns.adapter = VoltAdapter(volt220)

val volt = Structuraldesignpatterns.adapter.provideVoltFive()

println("After Structuraldesignpatterns.adapter, the volt is : $volt")After Structuraldesignpatterns.adapter, the volt is :5

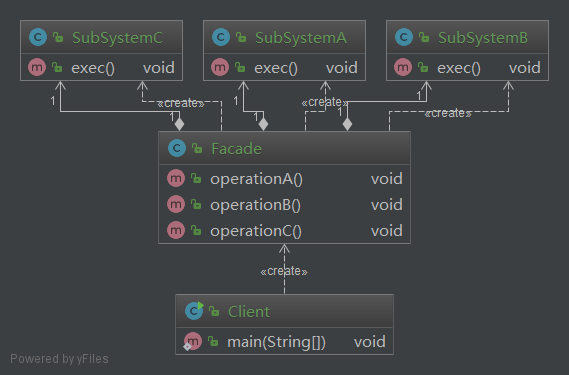

The facade pattern is used to define a simplified interface to a more complex subsystem.

interface Italykitchen {

fun lasagneWithTomatoAndCheese()

fun prawnRisotto()

fun creamCaramel()

}

class ItalykitchenImpl : Italykitchen {

override fun lasagneWithTomatoAndCheese() {

println("Lasagne With Tomato And Cheese")

}

override fun prawnRisotto() {

println("Prawn Risotto")

}

override fun creamCaramel() {

println("Cream Caramel")

}

}

interface Frenchkitchen {

fun bouillabaisse()

fun cassoulet()

fun pouleAuPot()

}

class FrenchkitchenImpl : Frenchkitchen {

override fun bouillabaisse() {

println("Bouillabaisse")

}

override fun cassoulet() {

println("Cassoulet")

}

override fun pouleAuPot() {

println("PouleAuPot")

}

}

class Menu {

private val italykitchen: Italykitchen

private val frenchkitchen: Frenchkitchen

init {

italykitchen = ItalykitchenImpl()

frenchkitchen = FrenchkitchenImpl()

}

fun bouillabaisse() {

frenchkitchen.bouillabaisse()

}

fun cassoulet() {

frenchkitchen.cassoulet()

}

fun pouleAuPot() {

frenchkitchen.pouleAuPot()

}

fun lasagneWithTomatoAndCheese() {

italykitchen.lasagneWithTomatoAndCheese()

}

fun prawnRisotto() {

italykitchen.prawnRisotto()

}

fun creamCaramel() {

italykitchen.creamCaramel()

}

}

val menu = Menu()

println("Customer order")

menu.lasagneWithTomatoAndCheese()

menu.creamCaramel()

println("===========New Order==========")

println("Customer two orders")

menu.bouillabaisse()

menu.prawnRisotto()Customer order

Lasagne With Tomato And Cheese

Cream Caramel

===========New Order==========

Customer two orders

Bouillabaisse

Prawn Risotto

Flyweight is a structural design pattern that lets you fit more objects into the available amount of RAM by sharing common parts of state between multiple objects instead of keeping all of the data in each object.

interface Ticket {

fun printTicket(time: String?, seat: String?)

}

object TicketFactory {

private val map: MutableMap<String, Ticket> = ConcurrentHashMap()

fun getTicket(movieName: String): Ticket? {

return if (map.containsKey(movieName)) {

map[movieName]

} else {

val ticket: Ticket = MovieTicket(movieName)

map[movieName] = ticket

ticket

}

}

}

class MovieTicket(private val movieName: String) : Ticket {

private val price: String

init {

price = "Price " + Random().nextInt(100)

}

override fun printTicket(time: String?, seat: String?) {

println("+-------------------+")

System.out.printf("| %-12s |\n", movieName)

println("| |")

System.out.printf("| %-12s|\n", time)

System.out.printf("| %-12s|\n", seat)

System.out.printf("| %-12s|\n", price)

println("| |")

println("+-------------------+")

}

}

val movieTicket1 = TicketFactory.getTicket("Transformers 5") as MovieTicket

movieTicket1.printTicket("14:00-16:30", "Seat D-5")

val movieTicket2 = TicketFactory.getTicket("Transformers 5") as MovieTicket

movieTicket2.printTicket("14:00-16:30", "Seat F-6")

val movieTicket3 = TicketFactory.getTicket("Transformers 5") as MovieTicket

movieTicket3.printTicket("18:00-22:30", "Seat A-2")+-------------------+

| Transformers 5 |

| |

| 14:00-16:30 |

| Seat D-5 |

| Price 33 |

| |

+-------------------+

+-------------------+

| Transformers 5 |

| |

| 14:00-16:30 |

| Seat F-6 |

| Price 33 |

| |

+-------------------+

+-------------------+

| Transformers 5 |

| |

| 18:00-22:30 |

| Seat A-2 |

| Price 33 |

| |

+-------------------+

In software engineering, behavioral design patterns are design patterns that identify common communication patterns between objects and realize these patterns. By doing so, these patterns increase flexibility in carrying out this communication.

Template Method is a behavioral design pattern that defines the skeleton of an algorithm in the superclass but lets subclasses override specific steps of the algorithm without changing its structure.

abstract class AssemblyLine {

protected open fun onProduceShell() {

println("Produce Shell")

}

protected open fun onProduceComponents() {

println("Produce some components")

}

protected open fun onAssemblyComponents() {

println("Assembly Components")

}

protected open fun onTestProducts() {

println("Test Products")

}

protected open fun onProductPacking() {

println("Product Packing")

}

fun product() {

println("+------Start Product------+")

onProduceShell()

onProduceComponents()

onAssemblyComponents()

onTestProducts()

onProduceComponents()

onProductPacking()

println("+------Finish Product------+")

}

}

class ComputerAssemblyLine : AssemblyLine() {

override fun onProduceShell() {

println("Product Aluminum housing and Liquid Crystal Display")

}

override fun onProduceComponents() {

println("Product Components and keyboard")

}

override fun onProductPacking() {

println("Pack and Mark the Apple trademark")

}

}class RadioAssemblyLine : AssemblyLine() {

override fun onProduceComponents() {

println("Product Radio Components and Antennas")

}

}

var assemblyLine: AssemblyLine = RadioAssemblyLine()

assemblyLine.product()

println()

assemblyLine = ComputerAssemblyLine()

assemblyLine.product()+------Start Product------+

Product Aluminum housing and Liquid Crystal Display

Product Components and keyboard

Assembly Components

Test Products

Product Components and keyboard

Pack and Mark the Apple trademark

+------Finish Product------+

+------Start Product------+

Produce Shell

Product Radio Components and Antennas

Assembly Components

Test Products

Product Radio Components and Antennas

Product Packing

+------Finish Product------+

The chain of responsibility pattern is used to process varied requests, each of which may be dealt with by a different handler.

abstract class Handler {

var successor: Handler? = null

abstract fun capital(): Int

abstract fun handle(money: Int)

fun handleRequest(money: Int) {

if (money <= capital()) {

handle(money)

} else {

if (null != successor) {

successor!!.handleRequest(money)

} else {

println("Your requested funds could not be approved")

}

}

}

}

class Tutor:Handler() {

override fun capital(): Int {

return 100

}

override fun handle(money: Int) {

println("Approved by the instructor: approved $money Dollar")

}

}class Secretary:Handler() {

override fun capital(): Int {

return 1000

}

override fun handle(money: Int) {

println("Secretary approved: approved $money Dollar")

}

}class Principal: Handler() {

override fun capital(): Int {

return 1000

}

override fun handle(money: Int) {

println("Approved by the principal: approved $money Dollar")

}

}

class Dean:Handler() {

override fun capital(): Int {

return 5000

}

override fun handle(money: Int) {

println("Dean approved: approved $money Dollar")

}

}

val tutor = Tutor()

val secretary = Secretary()

val dean = Dean()

val principal = Principal()

tutor.successor = secretary

secretary.successor = dean

dean.successor = principal

principal.successor = null

tutor.handleRequest(12000)

secretary.handleRequest(100)Your requested funds could not be approved

Secretary approved: approved 100 Dollar

The command pattern is used to express a request, including the call to be made and all of its required parameters, in a command object. The command may then be executed immediately or held for later use.

interface OrderCommand {

fun execute()

}

class OrderPayCommand(private val id: Long) : OrderCommand {

override fun execute() = println("Paying for order with id: $id")

}class OrderAddCommand(private val id:Long) : OrderCommand {

override fun execute() = println("Adding Order With id : $id")

}class CommandProcessor {

private val queue = ArrayList<OrderCommand>()

fun addToQueue(orderCommand: OrderCommand) :CommandProcessor =

apply {

queue.add(orderCommand)

}

fun processCommands():CommandProcessor =

apply {

queue.forEach{it.execute()}

queue.clear()

}

}

fun main() = command()

fun command() {

CommandProcessor()

.addToQueue(OrderAddCommand(1L))

.addToQueue(OrderAddCommand(2L))

.addToQueue(OrderPayCommand(2L))

.addToQueue(OrderPayCommand(1L))

.processCommands()

}Adding Order With id : 1

Adding Order With id : 2

Paying for order with id : 2

Paying for order with id : 1

Iterator is a behavioral design pattern that lets you traverse elements of a collection without exposing its underlying representation (list, stack, tree, etc.).

interface Iterator<T> {

operator fun hasNext(): Boolean

operator fun next(): T

}

interface BookIterable<T> {

operator fun iterator(): Iterator<T>?

}

class Book(private val name: String, private val ISBN: String, private val press: String) {

override fun toString(): String {

return "Book{" +

"name='" + name + '\'' +

", ISBN='" + ISBN + '\'' +

", press='" + press + '\'' +

'}'

}

}class Literature : BookIterable {

val literature: Array<Book?>

operator fun iterator(): Iterator {

return LiteratureIterator(literature)

}

init {

literature = arrayOfNulls(4)

literature[0] = Book("Three Kingdoms", "9787532237357", "Shanghai People's Fine Arts Publishing House")

literature[1] = Book("Journey to the West", "9787805200552", "Yuelu Publishing House")

literature[2] = Book("Water Margin", "9787020015016", "People's Literature Publishing House")

literature[3] = Book("Dream of Red Mansions", "9787020002207", "People's Literature Publishing House")

}

}class LiteratureIterator(private val literatures: Array<Book?>) : Iterator {

private var index = 0

operator fun hasNext(): Boolean {

return index < literatures.size - 1 && literatures[index] != null

}

operator fun next(): Book? {

return literatures[index++]

}

}fun main() {

val literature = Literature()

itr(literature.Behavioraldesignpatterns.iterator())

}

fun itr(Behavioraldesignpatterns.iterator: Iterator<T>) {

while (Behavioraldesignpatterns.iterator.hasNext()) {

println(Behavioraldesignpatterns.iterator.next())

}

}Book{name='Three Kingdoms', ISBN='9787532237357', press='Shanghai People's Fine Arts Publishing House'}

Book{name='Journey to the West', ISBN='9787805200552', press='Yuelu Publishing House'}

Book{name='Water Margin', ISBN='9787020015016', press='People's Literature Publishing House'}

Mediator design pattern is used to provide a centralized communication medium between different objects in a system. This pattern is very helpful in an enterprise application where multiple objects are interacting with each other.

class ChatMediator {

private val users: MutableList<ChatUser> = ArrayList()

fun sendMessage(msg: String, user: ChatUser) {

users

.filter { it != user }

.forEach {

it.receive(msg)

}

}

fun addUser(user: ChatUser): ChatMediator =

apply { users.add(user) }

}class ChatUser(private val mediator: ChatMediator, val name: String) {

fun send(msg: String) {

println("$name: Sending Message= $msg")

mediator.sendMessage(msg, this)

}

fun receive(msg: String) {

println("$name: Message received: $msg")

}

}

val mediator = ChatMediator()

val john = ChatUser(mediator, "Tamer")

mediator

.addUser(ChatUser(mediator, "Mohab"))

.addUser(ChatUser(mediator, "Mohand"))

.addUser(ChatUser(mediator, "Habiba"))

.addUser(john)

john.send("Hi everyone!")Mohab: Message received: Hi everyone!

Mohand: Message received: Hi everyone!

Habiba: Message received: Hi everyone!

The memento pattern is a software design pattern that provides the ability to restore an object to its previous state (undo via rollback).

data class Memento(val state: String)class CareTaker {

private val mementoList = ArrayList<Memento>()

fun saveState(state: Memento) {

mementoList.add(state)

}

fun restore(index: Int): Memento {

return mementoList[index]

}

}

class Originator(var state: String) {

fun createMemento(): Memento {

return Memento(state)

}

fun restore(memento: Memento) {

state = memento.state

}

}

val originator = Originator("initial Behavioraldesignpatterns.state")

val careTaker = CareTaker()

careTaker.saveState(originator.createMemento())

originator.state = "State #1"

originator.state = "State #2"

careTaker.saveState(originator.createMemento())

originator.state = "State #3"

println("Current State: " + originator.state)

originator.restore(careTaker.restore(1))

println("Second saved Behavioraldesignpatterns.state: " + originator.state)

originator.restore(careTaker.restore(0))

println("First saved Behavioraldesignpatterns.state: " + originator.state)Current State: State #3

Second saved Behavioraldesignpatterns.state: State #2

First saved Behavioraldesignpatterns.state: initial Behavioraldesignpatterns.state

The observer pattern is used to allow an object to publish changes to its state. Other objects subscribe to be immediately notified of any changes.

interface Observer {

fun update(magazine: String)

}

interface Subject {

fun registerObserver(observer: Observer)

fun removeObserver(observer: Observer)

fun notifyObservers()

}

class Magazine : Subject {

private val observerList: MutableList<Observer>

init {

observerList = ArrayList()

}

private var magazine: String? = null

override fun registerObserver(observer: Observer) {

observerList.add(observer)

}

override fun removeObserver(observer: Observer) {

observerList.remove(observer)

}

override fun notifyObservers() {

for (i in observerList.indices) {

val observer = observerList[i]

observer.update(magazine!!)

}

}

fun setMagazine(magazine: String?) {

this.magazine = magazine

notifyObservers()

}

}class Subscriber(magazine: Subject, subscriber: String) : Observer {

private val subscriber: String

override fun update(magazine: String) {

println("Dear$subscriber: Your magazine has arrived, and today’s magazine is called《$magazine》")

}

init {

magazine.registerObserver(this)

this.subscriber = subscriber

}

}class Bookstore(magazine: Subject) : Observer {

override fun update(magazine: String) {

println("Our shop updates the magazine today:《$magazine》")

}

init {

magazine.registerObserver(this)

}

} val magazine = Magazine()

val mohamed = Subscriber(magazine, "Mohamed")

val tamer = Subscriber(magazine, "Tamer")

val habiba = Subscriber(magazine, "Habiba")

val bookstore = Bookstore(magazine)

magazine.setMagazine("Shock! Today's magazine since...")DearMohamed: Your magazine has arrived, and today’s magazine is called《Shock! Today's magazine since...》

DearTamer: Your magazine has arrived, and today’s magazine is called《Shock! Today's magazine since...》

DearHabiba: Your magazine has arrived, and today’s magazine is called《Shock! Today's magazine since...》

Our shop updates the magazine today:《Shock! Today's magazine since...》

The state pattern is used to alter the behaviour of an object as its internal state changes. The pattern allows the class for an object to apparently change at run-time.

interface GameState {

fun killMonster()

fun gainExperience()

fun next()

fun pick()

}

class Player {

private lateinit var state: GameState

private fun setState(state: GameState?) {

this.state = state!!

}

fun gameStart() {

setState(GameStartState())

println("\n-----Game Start, ready to fight-----\n")

}

fun gameOver() {

setState(GameOverState())

println("\n----- Game Over -----\n")

}

fun killMonster() {

state.killMonster()

}

fun gainExperience() {

state.gainExperience()

}

operator fun next() {

state.next()

}

fun pick() {

state.pick()

}

}

class GameStartState : GameState {

override fun killMonster() {

println("Kill a Monster")

}

override fun gainExperience() {

println("Gain 5 EXP")

}

override operator fun next() {

println("Good! please enter next level")

}

override fun pick() {

println("Wow! You pick a good thing")

}

}

class GameOverState : GameState {

override fun killMonster() {

println("Please start game first")

}

override fun gainExperience() {}

override operator fun next() {

println("You want to challenge again?")

}

override fun pick() {

println("Please start game first")

}

} val player = Player()

player.gameStart()

player.killMonster()

player.gainExperience()

player.next()

player.pick()

player.gameOver()

player.next()

player.killMonster()

player.pick()-----Game Start, ready to fight-----

Kill a Monster

Gain 5 EXP

Good! please enter next level

Wow! You pick a good thing

----- Game Over -----

You want to challenge again?

Please start game first

Please start game first

The strategy pattern is used to create an interchangeable family of algorithms from which the required process is chosen at run-time.

interface Strategy {

fun transportation()

}class Context {

var goToStrategy:Strategy? = null

fun take() {

goToStrategy?.transportation()

}

}class GoToCairo : Strategy {

override fun transportation() {

println("take my car")

}

}class GoToGona:Strategy {

override fun transportation() {

println("take plane")

}

} val context = Context()

context.goToStrategy = GoToCairo()

context.take()

context.goToStrategy = GoToGona()

context.take()take my car

take plane

The visitor pattern is used to separate a relatively complex set of structured data classes from the functionality that may be performed upon the data that they hold.

interface Interviewer {

fun visit(student: Student)

fun visit(engineer: Engineer)

}

interface Applicant {

fun accept(visitor: Interviewer)

}

class Engineer(var name: String, var workExperience: Int, var projectNumber: Int) : Applicant {

override fun accept(visitor: Interviewer) {

visitor.visit(this)

}

}class Student(var name: String, var gpa: Double, var major: String) : Applicant {

override fun accept(visitor: Interviewer) {

visitor.visit(this)

}

}class Leader : Interviewer {

override fun visit(student: Student) {

println("Student " + student.name + "'s gpa is " + student.gpa)

}

override fun visit(engineer: Engineer) {

println(

"Engineer " + engineer.name + "'s number of projects is " + engineer.projectNumber

)

}

}class LaborMarket {

var applicants: MutableList<Applicant> = ArrayList()

fun showApplicants(visitor: Interviewer?) {

for (applicant in applicants) {

applicant.accept(visitor!!)

}

}

init {

applicants.add(Student("Tamer", 3.2, "Computer Science"))

applicants.add(Student("Mohamed", 3.4, "Network Engineer"))

applicants.add(Student("Habiba", 3.4, "Computer Science"))

applicants.add(Engineer("Ahmed", 4, 15))

applicants.add(Engineer("Mohand", 3, 10))

applicants.add(Engineer("Mohab", 6, 20))

}

}

val laborMarket = LaborMarket()

println("===== Round 1: Leader =====")

laborMarket.showApplicants(Leader())

/*

You can add more rounds and implements .............

*/===== Round 1: Leader =====

Student Tamer's gpa is 3.2

Student Mohamed's gpa is 3.4

Student Habiba's gpa is 3.4

Engineer Ahmed's number of projects is 15

Engineer Mohand's number of projects is 10

Engineer Mohab's number of projects is 20