-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

IPEP 23: Backbone.js Widgets

| Status | Active |

| Author | Jonathan Frederic <jon.freder@gmail.com> |

| Created | October 9, 2013 |

| Updated | October 17, 2013 |

| Implementation | #4374 |

! This document is incomplete !

Missing:

- Usage examples

- Message description

- Throttling description

- Message diff details

Typical scientific computing suites live within a hard-coded GUI (graphical user interface). This stereotype can be broken by exposing an API that allows the user to generate and manipulate their GUI. By adding this functionality to the IPython Notebook, users will be able to define the environment in which their code is executed. Prior to the addition of comms (IPEP 21: Widget Messages) this was not possible.

The Notebook Widget is introduced in this IPEP. Notebook Widgets are GUI elements in the Notebook front-end which are automatically synchronized with equivalent representations in the Notebook back-end. With the addition of Widgets, basic GUIs can be implemented completely in the back-end.

It’s important to understand that user written code in is generally executed in the back-end (traditionally Python, but also Julia, R, etc). Using the special magics %%javascript and %%html, users can write code that is executed on the front-end (in the web browser). The addition of comms allows for custom communication between front-end and back-end code.

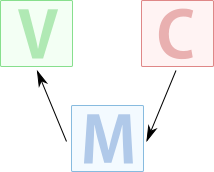

When designing the Widget architecture, we wanted to make sure that the widgets could be maximally reusable, configurable, and distributable. It is also important that the widgets themselves are independent of the data they represent. For this reason we decided to try to model our architecture after the MVC (model, view, and controller) design pattern. In the MVC pattern, the model contains all of the data, the view is used to render that data, and the controller is used to adjust the model (as seen in Figure 1). There are many Javascript libraries that aid in the creation of MVC architectures. We chose the backbone.js library to implement our architecture because it is lightweight and has a minimalistic impact on coding style.

|

| *Figure 1: Interaction of MVC components* |

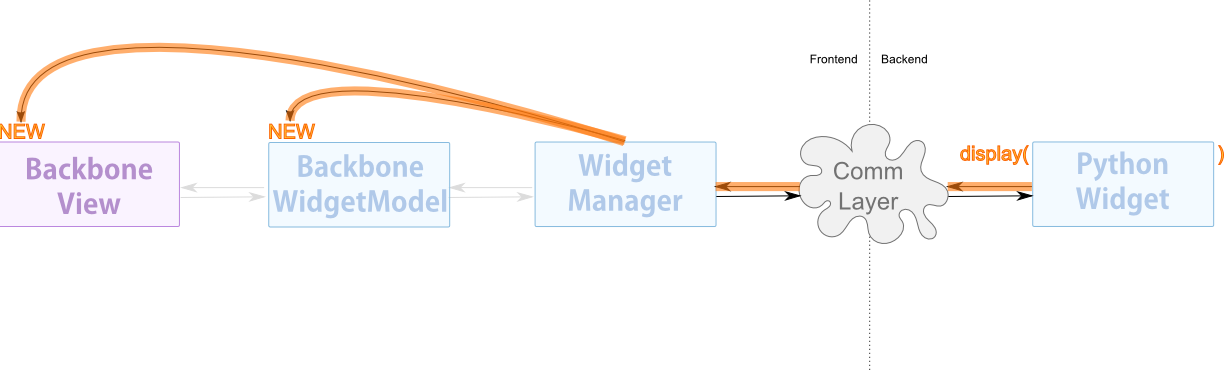

The MVC design pattern has to be altered to work within IPython. In the front-end, the view/controller is the backbone view and the model is the backbone model. In the back-end, a model is called a widget. The user can create a widget that is unattached to the front end (as seen in Figure 2).

|

| *Figure 2: Synchronization of each model in the front-end with the corresponding model in the back-end is done using a comm.* |

Usually backbone models are automatically synchronized (by the backbone machinery) with a RESTful server. All synchronization occurs through the Backbone.Sync(...) method. By overwriting the Backbone.Sync(...) function, all of the synchronization calls can be sent to the widget in the back-end using a comm.

In the Python back-end (other back-ends discussed later in this IPEP), traitlets are used to define each property of the model. The traitlets machinery listens for the properties to change. When a property is changed, the modified state of the model is sent to the front-end via a comm.

The backbone views have no counterpart in the back-end. This raises the first design question; How can users specify when and how a view should be displayed on the front-end via the back-end? The solution is to use IPython.display.display(...). When the IPython.display.display(...) method is called, a message is sent to the front-end instructing it to instanciate a backbone model and view (as seen in Figure 3).

|

| *Figure 3: Result of calling `IPython.display.display(...)`* |

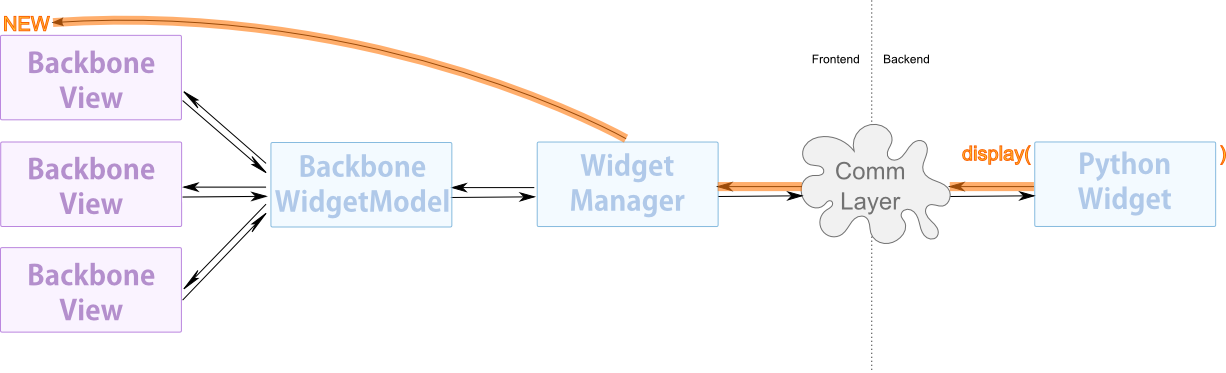

The IPython Notebook is designed so code is executed on a cell by cell basis. It would not be unusual to desire the same Widget to be available in more than one cell’s output. By calling IPython.display.display(...) again, the user can create another view linked to the same model (as seen in Figure 4).

|

| *Figure 4: Multiple views associated with one model* |

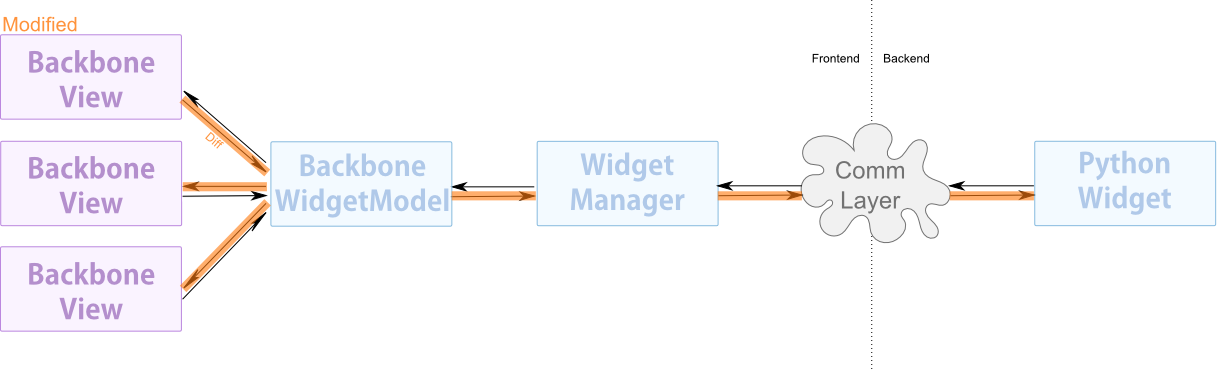

The beauty of this design is that model state is only sent once between the back-end and the front-end via the comm. The views are synchronized within the front-end (as seen in Figure 5).

|

| *Figure 5: Synchronization of the views to the model occurs completely within the front-end.* |

Models and views are separate entities. The user can choose what view is used for a model. The user can even create a custom view for an existing model. Since multiple views can be displayed for one model, the user can represent a model more than one way in a single cell’s output. For example, one could show a slider view and a numeric text box view for the same numeric model. This would allow the user to slide the slider or enter a value explicitly in the numeric text box. To choose what view is shown, one must pass the view’s name when calling the IPython.display.display(viewname="myview") method (replace "myview" with the view's name).

The second major design question arises because of the need to be able to nest views within each other; How can you display one view within another? Since nesting is only a function of the views, it’s hard to appropriately expose it in the back-end. The solution is to allow models in the back-end to be child of each other (as seen in Figure 6).

| /File/IPEP-23/Parent.png |

| *Figure 6: Model parent child relationships can exist on the Python side.* |

When the user calls IPython.display.display(...) and the model has a parent, the id of the parent is sent along with the show message to the front-end. When a user calls IPython.display.display(...) and the model has children, the children of that model are also shown (as seen in Figures 7-8).

| /File/IPEP-23/ParentShowStep1.png |

| *Figure 7: First step - parent view is rendered* |

| /File/IPEP-23/ParentShowStep2.png |

| *Figure 8: Second step - children views are rendered* |

When the front-end receives the command to show a view for a model that is child to another model, it looks to see if a view exists for the parent. If the parent view does exist, the child view is created within that parent view. If a parent doesn't already exist, the view is shown alone (without the parent).

Even though the child views are children of a parent view, they are still associated with their own models individually and state synchronization occurs between each view and its respective model. The information from a child view is never relayed to a parent view (as seen in Figure 9).

| /File/IPEP-23/ParentShowStep3.png |

| *Figure 9: A view always has a single unique model it is linked to, even if it is child to another view.* |

TODO

TODO