@(topic)

This repo is an organized collection of resources to help you learn java.

- Concurrent Programming in Java: Design Principles and Pattern (2nd Edition)

- Java Concurrency in Practice by Brian Goetz, Tim Peierls, Joshua Bloch, Joseph Bowbeer, David Holmes, and Doug Lea

- Effective Java Programming Language Guide (2nd Edition) by Joshua Bloch

- Concurrency: State Models & Java Programs (2nd Edition), by Jeff Magee and Jeff Kramer

- Java Concurrent Animated

In concurrent programming, there are two basic units of execution: processes and threads. In the Java programming language, concurrent programming is mostly concerned with threads. However, processes are also important.

Processes. A process has a self-contained execution environment. A process generally has a complete, private set of basic run-time resources; in particular, each process has its own memory space. Most implementations of the Java virtual machine run as a single process. A Java application can create additional processes using a ProcessBuilder object.

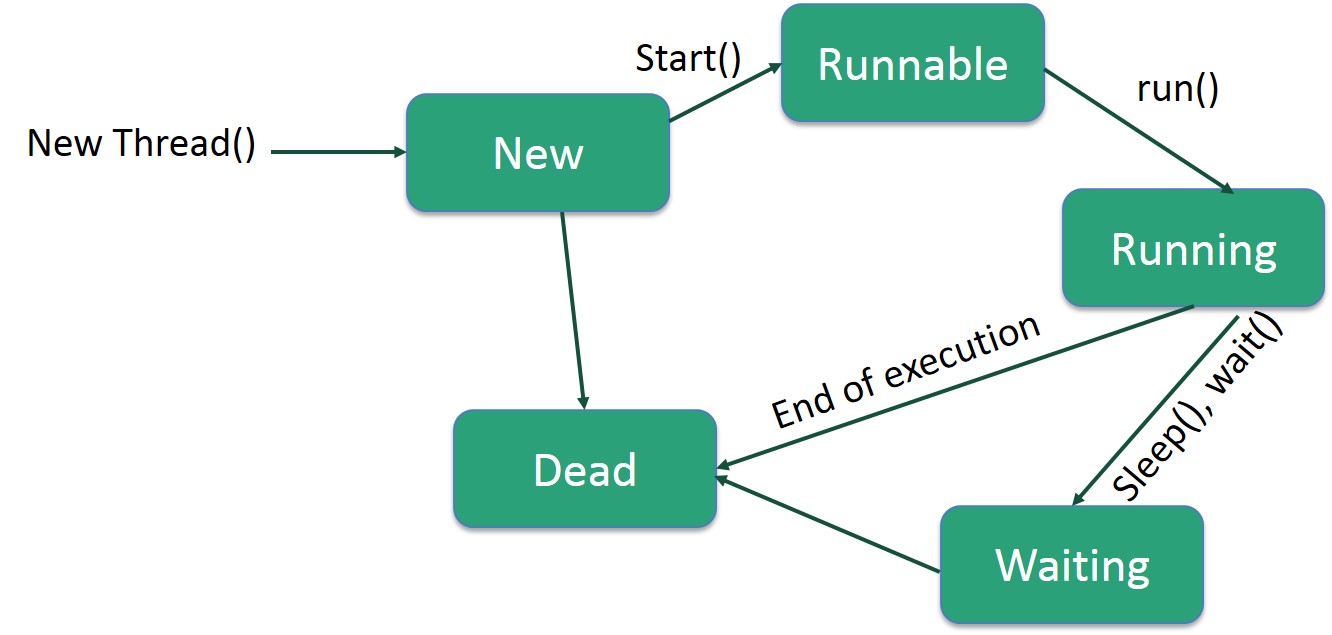

Threads. Threads are sometimes called lightweight processes. Both processes and threads provide an execution environment, but creating a new thread requires fewer resources than creating a new process. Threads exist within a process — every process has at least one. Threads share the process's resources, including memory and open files. This makes for efficient, but potentially problematic, communication. From the application programmer's point of view, you start with just one thread, called the main thread. This thread has the ability to create additional threads.

There are two ways to creates an instance of Thread: Provide a Runnable object and Subclass Thread

public class HelloRunnable implements Runnable {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Hello from a thread!");

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

(new Thread(new HelloRunnable())).start();

}

}

public class HelloThread extends Thread {

public void run() {

System.out.println("Hello from a thread!");

}

public static void main(String args[]) {

(new HelloThread()).start();

}

}A number of methods useful for thread management:

- Thread.sleep, causes the current thread to suspend execution for a specified period. This is an efficient means of making processor time available to the other threads of an application or other applications that might be running on a computer system.

- Thread.interrupt, An interrupt is an indication to a thread that it should stop what it is doing and do something else.

- Thread.join, allows one thread to wait for the completion of another.

The SimpleThreads Example

public class SimpleThreads {

// Display a message, preceded by

// the name of the current thread

static void threadMessage(String message) {

String threadName =

Thread.currentThread().getName();

System.out.format("%s: %s%n",

threadName,

message);

}

private static class MessageLoop

implements Runnable {

public void run() {

String importantInfo[] = {

"Mares eat oats",

"Does eat oats",

"Little lambs eat ivy",

"A kid will eat ivy too"

};

try {

for (int i = 0;

i < importantInfo.length;

i++) {

// Pause for 4 seconds

Thread.sleep(4000);

// Print a message

threadMessage(importantInfo[i]);

}

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

threadMessage("I wasn't done!");

}

}

}

public static void main(String args[])

throws InterruptedException {

// Delay, in milliseconds before

// we interrupt MessageLoop

// thread (default one hour).

long patience = 1000 * 60 * 60;

// If command line argument

// present, gives patience

// in seconds.

if (args.length > 0) {

try {

patience = Long.parseLong(args[0]) * 1000;

} catch (NumberFormatException e) {

System.err.println("Argument must be an integer.");

System.exit(1);

}

}

threadMessage("Starting MessageLoop thread");

long startTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

Thread t = new Thread(new MessageLoop());

t.start();

threadMessage("Waiting for MessageLoop thread to finish");

// loop until MessageLoop

// thread exits

while (t.isAlive()) {

threadMessage("Still waiting...");

// Wait maximum of 1 second

// for MessageLoop thread

// to finish.

t.join(1000);

if (((System.currentTimeMillis() - startTime) > patience)

&& t.isAlive()) {

threadMessage("Tired of waiting!");

t.interrupt();

// Shouldn't be long now

// -- wait indefinitely

t.join();

}

}

threadMessage("Finally!");

}

}synchronized, is all about different threads reading and writing to the same variables, objects and resources. This is not a trivial topic in Java, but here is a quote from Sun:

synchronizedmethods enable a simple strategy for preventing thread interference and memory consistency errors: if an object is visible to more than one thread, all reads or writes to that object's variables are done through synchronized methods.

In a very, very small nutshell: When you have two threads that are reading and writing to the same 'resource', say a variable named foo, you need to ensure that these threads access the variable in an atomic way. Without the synchronized keyword, your thread 1 may not see the change thread 2 made to foo, or worse, it may only be half changed. This would not be what you logically expect.

synchronized methods

public class SynchronizedCounter {

private int c = 0;

public synchronized void increment() {

c++;

}

public synchronized void decrement() {

c--;

}

public synchronized int value() {

return c;

}

}- First, it is not possible for two invocations of synchronized methods on the same object to interleave. When one thread is executing a synchronized method for an object, all other threads that invoke synchronized methods for the same object block (suspend execution) until the first thread is done with the object.

- Second, when a synchronized method exits, it automatically establishes a happens-before relationship with any subsequent invocation of a synchronized method for the same object. This guarantees that changes to the state of the object are visible to all threads.

synchronized statements

public void addName(String name) {

synchronized(this) {

lastName = name;

nameCount++;

}

nameList.add(name);

}In this example, the addName method needs to synchronize changes to lastName and nameCount, but also needs to avoid synchronizing invocations of other objects' methods. (Invoking other objects' methods from synchronized code can create problems that are described in the section on Liveness.) Without synchronized statements, there would have to be a separate, unsynchronized method for the sole purpose of invoking nameList.add.

A concurrent application's ability to execute in a timely manner is known as its liveness.

Deadlock describes a situation where two or more threads are blocked forever, waiting for each other. Here's an example.

public class Deadlock {

static class Friend {

private final String name;

public Friend(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return this.name;

}

public synchronized void bow(Friend bower) {

System.out.format("%s: %s"

+ " has bowed to me!%n",

this.name, bower.getName());

bower.bowBack(this);

}

public synchronized void bowBack(Friend bower) {

System.out.format("%s: %s"

+ " has bowed back to me!%n",

this.name, bower.getName());

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

final Friend alphonse =

new Friend("Alphonse");

final Friend gaston =

new Friend("Gaston");

new Thread(new Runnable() {

public void run() { alphonse.bow(gaston); }

}).start();

new Thread(new Runnable() {

public void run() { gaston.bow(alphonse); }

}).start();

}

}Starvation, describes a situation where a thread is unable to gain regular access to shared resources and is unable to make progress.

Livelock, A thread often acts in response to the action of another thread. If the other thread's action is also a response to the action of another thread, then livelock may result.

Threads often have to coordinate their actions. The most common coordination idiom is the guarded block. Such a block begins by polling a condition that must be true before the block can proceed. There are a number of steps to follow in order to do this correctly.

Suppose, for example guardedJoy is a method that must not proceed until a shared variable joy has been set by another thread. Such a method could, in theory, simply loop until the condition is satisfied, but that loop is wasteful, since it executes continuously while waiting.

public void guardedJoy() {

// Simple loop guard. Wastes

// processor time. Don't do this!

while(!joy) {}

System.out.println("Joy has been achieved!");

}A more efficient guard invokes Object.wait to suspend the current thread. The invocation of wait does not return until another thread has issued a notification that some special event may have occurred — though not necessarily the event this thread is waiting for:

public synchronized void guardedJoy() {

// This guard only loops once for each special event, which may not

// be the event we're waiting for.

while(!joy) {

try {

wait();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {}

}

System.out.println("Joy and efficiency have been achieved!");

}When wait is invoked, the thread releases the lock and suspends execution. At some future time, another thread will acquire the same lock and invoke Object.notifyAll, informing all threads waiting on that lock that something important has happened:

public synchronized notifyJoy() {

joy = true;

notifyAll();

}An object is considered immutable if its state cannot change after it is constructed.

SynchronizedRGB, defines objects that represent colors. Each object represents the color as three integers that stand for primary color values and a string that gives the name of the color.

public class SynchronizedRGB {

// Values must be between 0 and 255.

private int red;

private int green;

private int blue;

private String name;

private void check(int red,

int green,

int blue) {

if (red < 0 || red > 255

|| green < 0 || green > 255

|| blue < 0 || blue > 255) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

}

}

public SynchronizedRGB(int red,

int green,

int blue,

String name) {

check(red, green, blue);

this.red = red;

this.green = green;

this.blue = blue;

this.name = name;

}

public void set(int red,

int green,

int blue,

String name) {

check(red, green, blue);

synchronized (this) {

this.red = red;

this.green = green;

this.blue = blue;

this.name = name;

}

}

public synchronized int getRGB() {

return ((red << 16) | (green << 8) | blue);

}

public synchronized String getName() {

return name;

}

public synchronized void invert() {

red = 255 - red;

green = 255 - green;

blue = 255 - blue;

name = "Inverse of " + name;

}

}SynchronizedRGB must be used carefully to avoid being seen in an inconsistent state. If another thread invokes color.set after Statement 1 but before Statement 2, the value of myColorInt won't match the value of myColorName. So the two statements must be bound together

synchronized (color) {

int myColorInt = color.getRGB(); //Statement 1

String myColorName = color.getName(); //Statement 2

}A Strategy for Defining Immutable Objects

- Don't provide "setter" methods — methods that modify fields or objects referred to by fields.

- Make all fields final and private.

- Don't allow subclasses to override methods. The simplest way to do this is to declare the class as final. A more sophisticated approach is to make the constructor private and construct instances in factory methods.

- If the instance fields include references to mutable objects, don't allow those objects to be changed:

- Don't provide methods that modify the mutable objects.

- Don't share references to the mutable objects. Never store references to external, mutable objects passed to the constructor; if necessary, create copies, and store references to the copies. Similarly, create copies of your internal mutable objects when necessary to avoid returning the originals in your methods.

final public class ImmutableRGB {

// Values must be between 0 and 255.

final private int red;

final private int green;

final private int blue;

final private String name;

private void check(int red,

int green,

int blue) {

if (red < 0 || red > 255

|| green < 0 || green > 255

|| blue < 0 || blue > 255) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

}

}

public ImmutableRGB(int red,

int green,

int blue,

String name) {

check(red, green, blue);

this.red = red;

this.green = green;

this.blue = blue;

this.name = name;

}

public int getRGB() {

return ((red << 16) | (green << 8) | blue);

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

public ImmutableRGB invert() {

return new ImmutableRGB(255 - red,

255 - green,

255 - blue,

"Inverse of " + name);

}

}Lock Objects, to solve the deadlock problem we saw in Liveness.

import java.util.concurrent.locks.Lock;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock;

import java.util.Random;

public class Safelock {

static class Friend {

private final String name;

private final Lock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public Friend(String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public String getName() {

return this.name;

}

public boolean impendingBow(Friend bower) {

Boolean myLock = false;

Boolean yourLock = false;

try {

myLock = lock.tryLock();

yourLock = bower.lock.tryLock();

} finally {

if (! (myLock && yourLock)) {

if (myLock) {

lock.unlock();

}

if (yourLock) {

bower.lock.unlock();

}

}

}

return myLock && yourLock;

}

public void bow(Friend bower) {

if (impendingBow(bower)) {

try {

System.out.format("%s: %s has"

+ " bowed to me!%n",

this.name, bower.getName());

bower.bowBack(this);

} finally {

lock.unlock();

bower.lock.unlock();

}

} else {

System.out.format("%s: %s started"

+ " to bow to me, but saw that"

+ " I was already bowing to"

+ " him.%n",

this.name, bower.getName());

}

}

public void bowBack(Friend bower) {

System.out.format("%s: %s has" +

" bowed back to me!%n",

this.name, bower.getName());

}

}

static class BowLoop implements Runnable {

private Friend bower;

private Friend bowee;

public BowLoop(Friend bower, Friend bowee) {

this.bower = bower;

this.bowee = bowee;

}

public void run() {

Random random = new Random();

for (;;) {

try {

Thread.sleep(random.nextInt(10));

} catch (InterruptedException e) {}

bowee.bow(bower);

}

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

final Friend alphonse =

new Friend("Alphonse");

final Friend gaston =

new Friend("Gaston");

new Thread(new BowLoop(alphonse, gaston)).start();

new Thread(new BowLoop(gaston, alphonse)).start();

}

}Multiple lock object implementations are available in the standard JDK

- ReentrantLock, A reentrant mutual exclusion Lock with the same basic behavior and semantics as the implicit monitor lock accessed using synchronized methods and statements, but with extended capabilities.

- ReadWriteLock, The interface ReadWriteLock specifies another type of lock maintaining a pair of locks for read and write access. The idea behind read-write locks is that it's usually safe to read mutable variables concurrently as long as nobody is writing to this variable.

- StampedLock, Java 8 ships with a new kind of lock called StampedLock which also support read and write locks just like in the example above. In contrast to ReadWriteLock the locking methods of a StampedLock return a stamp represented by a long value.

Executors Interfaces, The java.util.concurrent package defines three executor interfaces:

- Executor, a simple interface that supports launching new tasks.

- ExecutorService, a subinterface of Executor, which adds features that help manage the lifecycle, both of the individual tasks and of the executor itself.

- ScheduledExecutorService, a subinterface of ExecutorService, supports future and/or periodic execution of tasks.

Thread Pools, Most of the executor implementations in java.util.concurrent use thread pools, which consist of worker threads.

- newFixedThreadPool, Creates a thread pool that reuses a fixed number of threads operating off a shared unbounded queue. At any point, at most nThreads threads will be active processing tasks. If additional tasks are submitted when all threads are active, they will wait in the queue until a thread is available. If any thread terminates due to a failure during execution prior to shutdown, a new one will take its place if needed to execute subsequent tasks. The threads in the pool will exist until it is explicitly shutdown.

- newCachedThreadPool, Creates a thread pool that creates new threads as needed, but will reuse previously constructed threads when they are available. These pools will typically improve the performance of programs that execute many short-lived asynchronous tasks. Calls to execute will reuse previously constructed threads if available. If no existing thread is available, a new thread will be created and added to the pool. Threads that have not been used for sixty seconds are terminated and removed from the cache. Thus, a pool that remains idle for long enough will not consume any resources. Note that pools with similar properties but different details (for example, timeout parameters) may be created using ThreadPoolExecutor constructors.

Fork/Join, an implementation of the ExecutorService interface that helps you take advantage of multiple processors. It is designed for work that can be broken into smaller pieces recursively.

Concurrent Collections, The java.util.concurrent package includes a number of additions to the Java Collections Framework. These are most easily categorized by the collection interfaces provided:

- BlockingQueue defines a first-in-first-out data structure that blocks or times out when you attempt to add to a full queue, or retrieve from an empty queue.

- ConcurrentMap is a subinterface of java.util.Map that defines useful atomic operations. These operations remove or replace a key-value pair only if the key is present, or add a key-value pair only if the key is absent. Making these operations atomic helps avoid synchronization. The standard general-purpose implementation of ConcurrentMap is ConcurrentHashMap, which is a concurrent analog of HashMap.

- ConcurrentNavigableMap is a subinterface of ConcurrentMap that supports approximate matches. The standard general-purpose implementation of ConcurrentNavigableMap is ConcurrentSkipListMap, which is a concurrent analog of TreeMap.

Atomic Variables

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

class AtomicCounter {

private AtomicInteger c = new AtomicInteger(0);

public void increment() {

c.incrementAndGet();

}

public void decrement() {

c.decrementAndGet();

}

public int value() {

return c.get();

}

}Concurrent Random Numbers, For concurrent access, using ThreadLocalRandom instead of Math.random() results in less contention and, ultimately, better performance.

int r = ThreadLocalRandom.current() .nextInt(4, 77);In software engineering, the singleton pattern is a software design pattern that restricts the instantiation of a class to one object. This is useful when exactly one object is needed to coordinate actions across the system.

The Right Way to Implement a Serializable Singleton in Java.

public enum Elvis {

INSTANCE;

private final String[] favoriteSongs =

{ "Hound Dog", "Heartbreak Hotel" };

public void printFavorites() {

System.out.println(Arrays.toString(favoriteSongs));

}

}This approach is functionally equivalent to the public field approach, except that it is more concise, provides the serialization machinery for free, and provides an ironclad guarantee against multiple instantiation, even in the face of sophisticated serialization or reflection attacks. While this approach has yet to be widely adopted, a single-element enum type is the best way to implement a singleton.

Before release 1.5, there were two ways to implement singletons. Both are based on keeping the constructor private and exporting a public static member to provide access to the sole instance. In one approach, the member is a final field:

// Singleton with public final field

public class Elvis {

public static final Elvis INSTANCE = new Elvis();

private Elvis() { ... }

public void leaveTheBuilding() { ... }

}In the second approach to implementing singletons, the public member is a static factory method.

public final class Singleton {

private static final Singleton INSTANCE = new Singleton();

private Singleton() {}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

return INSTANCE;

}

}and the second approach with lazy initialization, where the instance is created when the static method is first invoked

public final class Singleton {

private static volatile Singleton instance = null;

private Singleton() {}

public static Singleton getInstance() {

if (instance == null) {

synchronized(Singleton.class) {

if (instance == null) {

instance = new Singleton();

}

}

}

return instance;

}

}