Implementation of an interpreter for the given source program represented as three-address code (abbrv. 3-AC) instructions stored in XML format. The interpreter will be a console application implemented in Python 3. The program will:

- Parse the command-line option(s) to get the filename with the input program to interpret.

- Open and parse the input file using an XML parser to get an internal representation (in the form of 3-AC) of the given source program.

- Interpret the given program instruction by instruction according to the following specifications. If some reading and writing is required, use the standard input (stdin) and standard output (stdout).

The interpreter will be a console application (i.e. no graphical user interface) that takes one mandatory command-line argument with the filename of the source program with the 3-AC instructions in XML format. The filename can be given also with relative or absolute path.

python3 taci.py input.xml

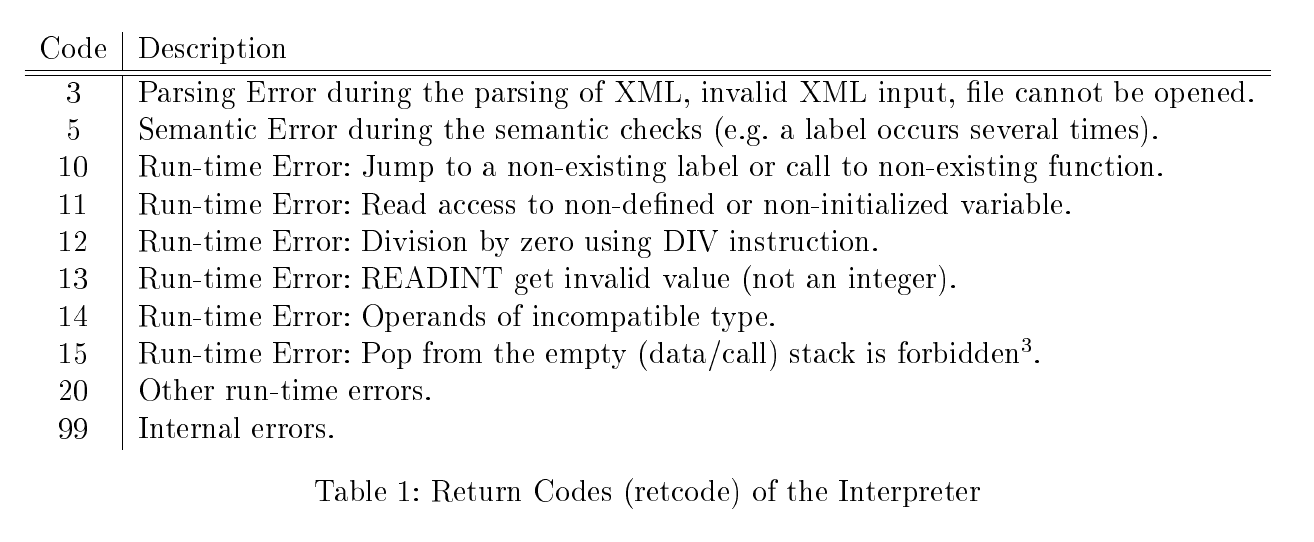

If the interpretation of the given program works without errors, the interpreter returns zero (0) as its returning code. If an error occurs, the returning code will be according to Table 1.

3-AC instructions are represented in XML. The input XML file will be always well-formed and valid according to its document type definition (DTD) (see Listing 1). Every valid input XML file will contain its DTD from Listing 1.

<!ELEMENT program (taci+)>

<!ELEMENT taci (dst?,src1?,src2?)>

<!ELEMENT dst (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT src1 (#PCDATA)>

<!ELEMENT src2 (#PCDATA)>

<!ATTLIST program name CDATA #IMPLIED>

<!ATTLIST taci opcode CDATA #REQUIRED>

<!ATTLIST dst kind (literal|variable) "variable">

<!ATTLIST dst type (integer|string) "integer">

<!ATTLIST src1 kind (literal|variable) "variable">

<!ATTLIST src1 type (integer|string) "integer">

<!ATTLIST src2 kind (literal|variable) "variable">

<!ATTLIST src2 type (integer|string) "integer">

<!ENTITY language "IPPe Three-Address Code">

<!ENTITY eol "

">

<!ENTITY lt "<">

<!ENTITY gt ">">

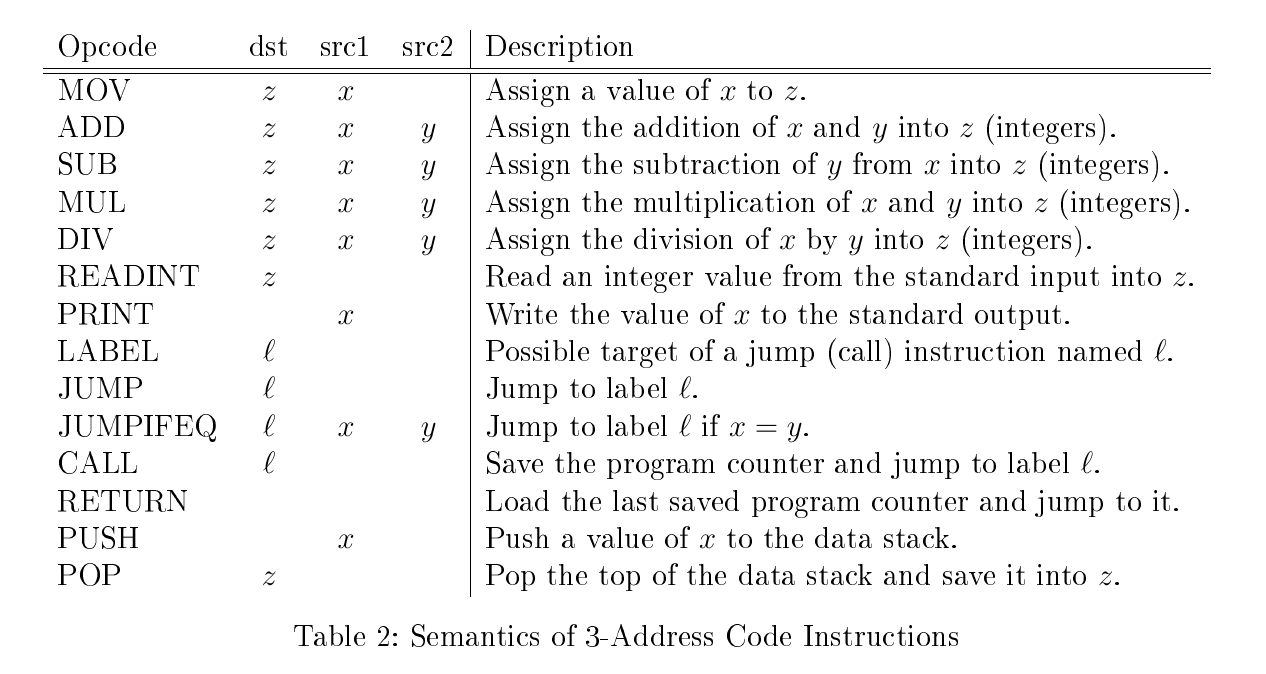

]>In principle, an instruction written in 3-AC consists of four parts: (1) operation code, (2) destination, (3) first source, and (4) second source. (2), (3), and (4) are called arguments. In fact, some instructions use only some of the arguments and they are either addresses (variables) or literals (constants and labels). The kind of the argument is given by variable or literal value in XML attribute kind. Commonly, the operation code is a keyword describing the action/operation that is taken when the instruction is interpreted; the destination address describes where the result of the action will be stored; the first and the second source are operands of the operation. The opcodes and arguments are all case-sensitive so upper-case/lowercase letters matter in identifiers and keywords. Arguments of an opcode are dynamically typed. 3-AC supports only integer numbers (by default) and strings.

A variable identifier is defined as a non-empty sequence of letters (lowercase/uppercase), digits, and underscore character ("_") starting with a letter or underscore. An integer literal is a constant (decimal base) and consists of a sequence of digits that can be prefixed by a sign (e.g. 42, -6 or +9). The type is identified by integer keyword in XML attribute type of the arguments. A string literal is just a content of the corresponding XML element (string keyword). It can contain the end of line symbol (use &eol; entity) and few other entities in the XML input file. For the complete list of 3-AC instructions supported by the interpreter, see Table 2. x, y are variable names or literals. z is a variable name or label.

Additionally, some more operations are available in the interpreter:

- READSTR str - Read a string from the standard input into str variable.

- CONCAT z,x,y - Assign the concatenation of x and y into z (strings).

- GETAT dst,src,i - Assign the one-character string at index i of string src into dst (string).

- LEN dst,src - Assign the length of src (string) into dst (integer).

- STRINT dst,src - Convert a string src into an integer variable dst.

- INTSTR dst,src - Convert an integer src into a string variable dst.

- JUMPIFGR z,x,y - Jump to label z if x > y.

The 3-AC instruction of the following form:

OPCODE z, x, y;

which is represented in XML as shown in next listing.

<taci opcode="OPCODE">

<dst>z</dst>

<src1>x</src1>

<src2>y</src2>

</taci>The start point of the whole program is the first 3-AC instruction. A variable that was already declared can be re-declared (including the change of its type) if used as a destination variable.

Note that CALL and RETURN instructions use call stack to store/load program counter.

You can find some examples of this 3-Address code XML programs in tests directory.

This project contains two scripts in Python language: tacy.py and interpreter.py, which holds most of the functionality of the interpreter.

Tacy.py is the main script of the project. It just takes the XML file we want to process, creates a interpreter and runs it, there’s nothing else.

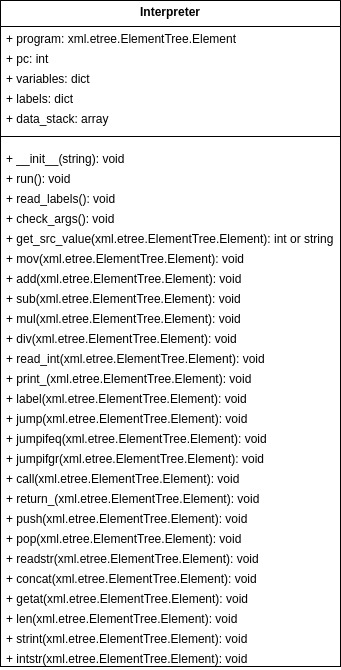

Let’s talk about the interpreter. Thinking about the different possible implementations, I decide to use the object oriented programming, specifically creating a class Interpreter, which needs a XML file as argument for creating the decoder and running it. With this implementation, we need an object for every XML file we want to process, as I think it’s the best approach according to the specification. In addition, we improve the reutilization of the code, facilitating the use of the interpreter in other projects.

The class Interpreter will use the tree of the XML file, a program counter and some data structures (variables, labels, data stack) as attributes. There’s no need for storing more information in the interpreter according to the description. The creation of an object of this class just loads the XML file, but it doesn’t run it. For that task, it is needed to call the method run.

This run method will interpret all instructions of the program held on the XML file, but firstly we should make some syntax check, as well as reading all labels. After that, we can execute all the instructions if any error isn’t found.

For executing the commands, it loads the operation code, checks the arguments and performs the operations. Subsequently, it increases the program counter by one and executes the next instruction, if exists. If not, it just finished the execution with code 0. There are also several methods for executing every operation and some auxiliary methods:

- read_labels (taci): reads all labels and stores them with its operation number.

- check_args (taci): checks arguments (src1, src2, dst) syntax.

- get_src_value (arg): returns the value of the source arg, according to its kind and type.

Let’s discuss some possible future implementations. I think the main one could be a debugger for the interpreter, allowing us to take more control of the execution and find errors. For this task, we would need to create a class Debugger , which would contain an object of the class Interpreter and some auxiliary information for debugging. With this design, we make sure one of the bases of the initial implementation is still alive: it’s needed an object for every XML file we want to interpret.

Other possible improvements could be adding support for more typical data structures, such as floats, booleans, arrays, dictionaries, etc, and their correspondent functionality, helping us to create a more complex system with several different uses.