- Clean Architecture with MVI (Uni-directional data flow)

- Kotlin Coroutines with Flow

- Dagger Hilt

- Kotlin Gradle DSL

- GitHub actions for CI

Hi 👋🏼👋🏼👋🏼 Thanks for checking out my project. For the rest of this document, I will be explaining the reasons for the technical decisions I made for this case study, the problems I faced, and what I learnt from them.

To build this project, you require:

- Android Studio 4.2 canary 7 or higher

- Gradle 6.5

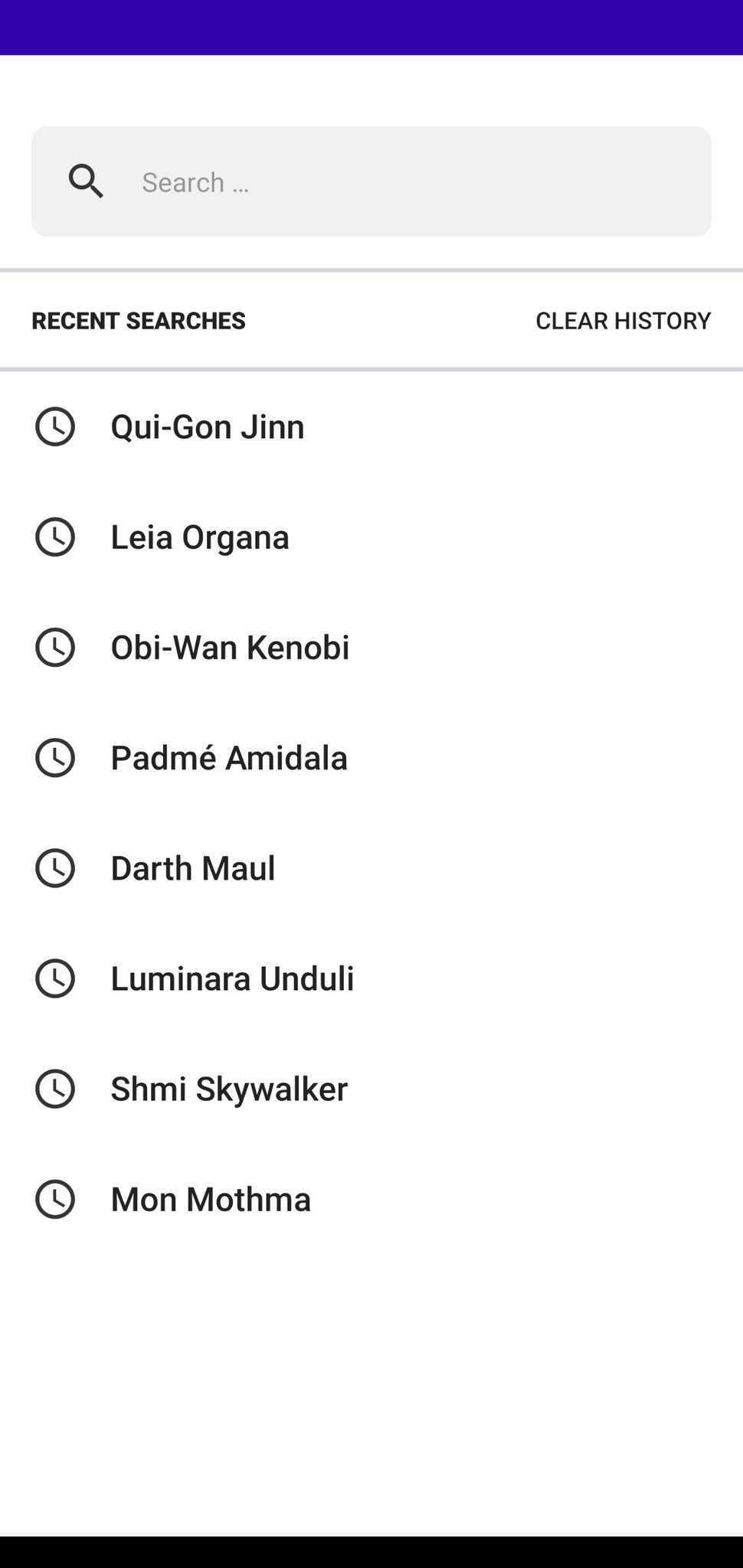

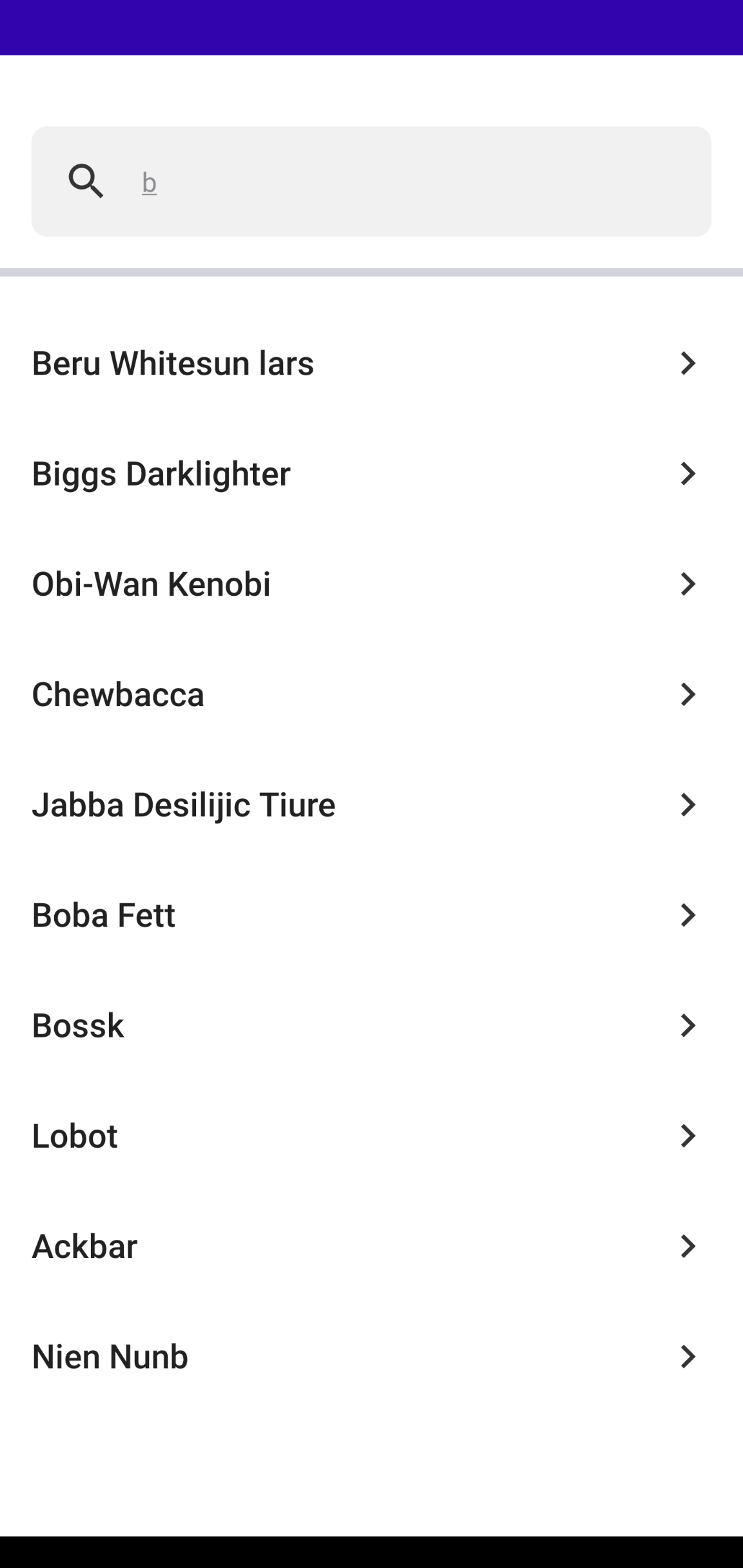

Before taking any coding and architecture decisions, I first had to come up with an idea of how I wanted the app to look, and the kind of experience I wanted users to have when using the app. This also guided my decisions on what architecture and tools were best suited to bring about a good user experience. In addition to having a search screen and a detail screen, I also added a search history screen where users can revisit any previously viewed character without having to search and wait for results. As seen in the images of the app above, the app launches into the search screen where the user can either see their search history or a prompt that tells them that their recent searches will be displayed there later. There's also a button that allows the user clear their search history.

Typing text into the search bar transitions the user into a searching state which leads to either a loaded search results state, empty or error state.

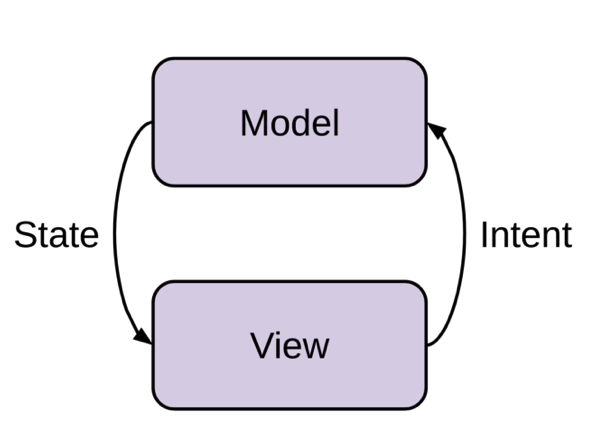

Seeing that the app requires a lot of state handling, I opted to use the Model-View-Intent architecture for the presentation layer of the app. This will be discussed in-depth in the section below.

The application follows clean architecture because of the benefits it brings to software which includes scalability, maintainability and testability. It enforces separation of concerns and dependency inversion, where higher and lower level layers all depend on abstractions. In the project, the layers are separated into different gradle modules namely:

- Domain

- Data

- Remote

- Cache

These modules are Kotlin modules except the cache module. The reason being that the low level layers need to be independent of the Android framework. One of the key points of clean architecture is that low level layers should be platform agnostic. As a result, the domain, data and presentation layers can be plugged into a kotlin multiplatform project for example, and it will run just fine because we don't depend on the android framework.

The cache and remote layers are implementation details that can be provided in any form (Firebase, GraphQl server, REST, ROOM, SQLDelight, etc) as long as it conforms to the business rules / contracts defined in the data layer which in turn also conforms to contracts defined in domain.

The project has one feature module character_search that holds the UI code and presents data to the users. The main app module does nothing more than just tying all the layers of our app together.

For dependency injection and asynchronous programming, the project uses Dagger Hilt and Coroutines with Flow. Dagger Hilt is a fine abstraction over the vanilla dagger boilerplate, and is easy to setup. Coroutines and Flow brings kotlin's expressibility and conciseness to asynchronous programming, along with a fine suite of operators that make it a robust solution.

As stated earlier, the presentation layer is implemented with MVI architecture. The project has a kotlin module called presentation which defines the contract that presenters should implement. The layer is also platform agnostic, making it easy to change implementation details (ViewModel, etc).

MVI architecture has two main components - The model and the view, everything else is the data that flows between these two components. The view state comes from the Model and goes into the View for rendering. Intents come from the View and are consumed by the Model for processing. As a result, the data flow is unidirectional.

The project contains a class called State machine which encapsulates logic of how to process intents and make new view state. It relies on an intent processor that takes intents from the view, liases with a third-party (in this case our domain layer) to process the intent and then returns a result. A view state reducer takes in the result and the previous state to compute a new view state.

The views (fragments/components) output intents and take state as input.

The Viewmodel which is the presenter implementation is very lean, depending solely on the state machine. The reason for using the Jetpack Viewmodel is that it survives configuration changes, and thus ensures that the view state is persisted across screen rotation.

MVI is a good architecture to use when you don't want any surprises in user experience as state only comes from one source and is immutable. On the other hand, it does come with a lot of boilerplate. Thankfully, there are a couple of libraries that abstract the implementation details (Mosby, FlowRedux, MvRX) and make it a lot easier to use. This case study has more of a bare bones implementation which represents the core concepts of MVI.

For each screen, there is a sealed class of View state, View intent and results. It's also possible to want to render multiple view states in one screen, leading to the use of view components.

View components are reusable UI components that extend a viewGroup, which knows how to render its own view state and send intents. In the search screen we have two components - SearchHistoryView and SearchResultView. The SearchFragment then passes state to these components to render on the screen. It also takes intents from the components to process.

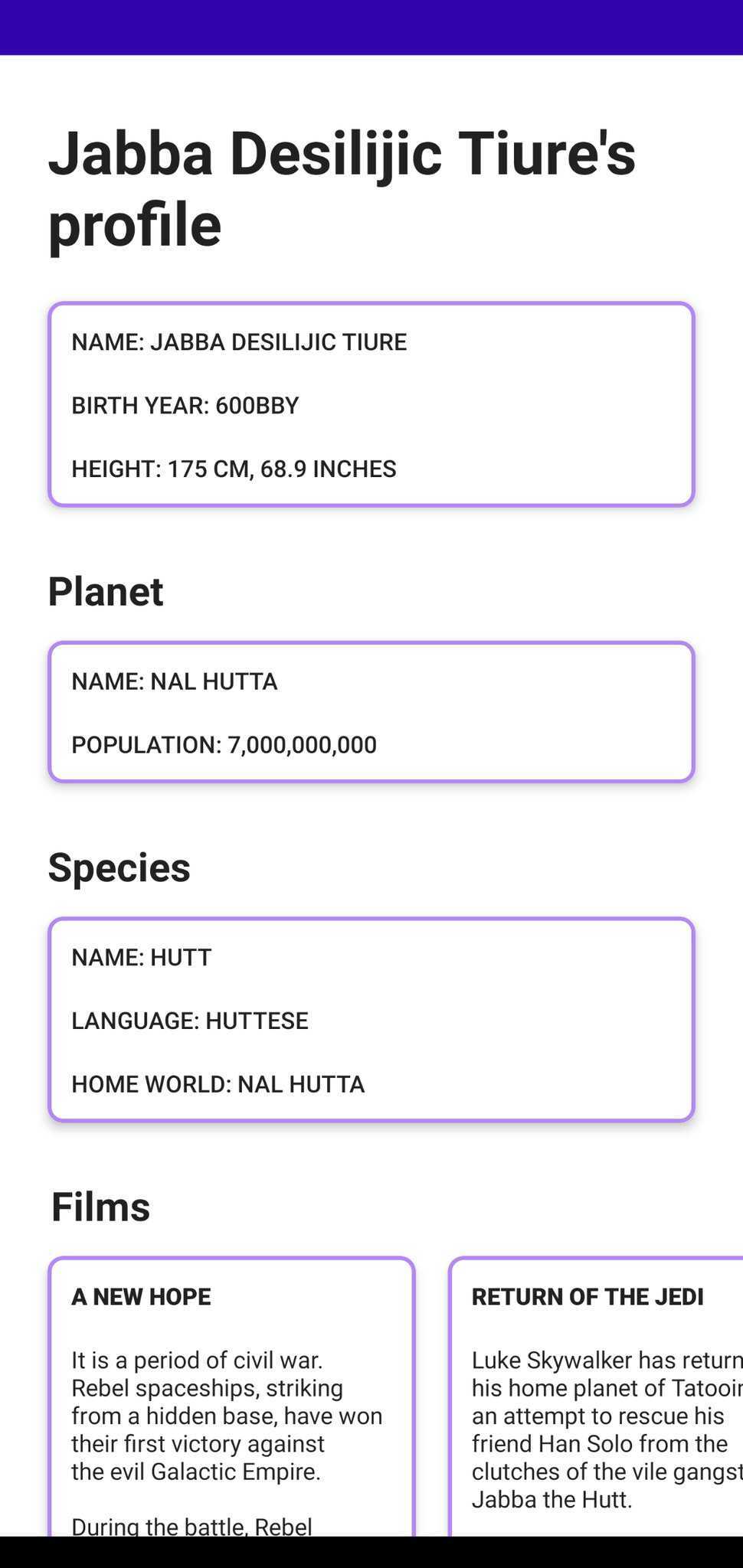

The detail screen is a bit more complex requiring 4 view components to render each detail - PlanetView, FilmView, SpeciesView, and ProfileView. These views encapsulate logic for rendering success, error and empty states for the corresponding detail. The data for the views are fetched concurrently, allowing any of the views to render whenever its data is available. It also allows the user to retry the data fetch for each individual component if it fails. The state for each of view is decoupled from one another and is cached in a Flow persisted in the Fragment's Viewmodel.

The domain layer contains the app business logic. It defines contracts for data operations and domain models to be used in the app. All other layers have their own representation of these domain models, and Mapper classes (or adapters) are used to transform the domain models to each layer's domain model representation. Usecases which represent a single unit of business logic are also defined in the domain layer, and are consumed by the presentation layer. Writing mappers and models can take a lot of effort and result in boilerplate, but they make the codebase much more maintainable and robust by separating concerns.

The Data layer implements the contract for providing data defined in the domain layer, and it in turn provides a contract that will be used to fetch data from the remote and cache data sources.

We have two data sources - Remote and Cache. Remote relies on Retrofit library to fetch data from the swapi.dev REST api, while the cache layer uses Room library to persist the search history.

The remote layer contains an OkHttp Interceptor that modifies api requests and changes their scheme from http to the more secure https to fix an issue where the swapi.dev api returns non https urls for fetching character detail. It also has another interceptor that modifies internet connectivity error exceptions (SocketTimeout, UnknownHost, etc) to convey an error message the user will understand.

Testing is done with Junit4 testing framework, and with Google Truth for making assertions. The test uses fake objects for all tests instead of mocks, making it easier to verify interactions between objects and their dependencies, and simulate the behavior of the real objects. Each layer has its own tests. The remote layer makes use of Mockwebserver to test the api requests and verify that mock Json responses provided in the test resource folder are returned. The cache layer includes tests for the Room data access object (DAO), ensuring that data is saved and retrieved as expected. The use cases in domain are also tested to be sure that they are called with the required parameters or throw a NoParams exception.

The presentation layer is extensively unit-tested to ensure that the correct view state is produced when an intent is processed. The intent processors are tested to ensure that they produce the right results for each intent. The view state reducer tests then verify that the correct view state is computed from those results. Viewmodel tests verify that each call to process an Intent produces the correct view state. It looks trivial since it is similar to the reducer test but it is still very important.

The case study can do with more UI tests that verify that the view state is rendered as expected. However, the extensive unit and integration test coverage ensures that the app works as expected.

The gradle script uses Kotlin Gradle DSL which brings Kotlin's rich language features to gradle configuration. The project also uses ktlint and the spotless plugin to enforce proper code style. Github actions handles continous integration, and runs ktlint and unit tests. There's also a Ktlint pre-commit and pre-push git hook that verifies the project's code style before committing code or pushing to remote repository.