Repository for HackBU Demo on Go

Most of the code in this demo is adopted from https://www.tutorialspoint.com/go/go_overview.htm and https://tour.golang.org. These are great resources to start learning Go on your own.

Go programming implementations use a traditional compile and link model to generate executable binaries. The Go programming language was announced in November 2009 and is used in some of the Google's production systems.

Some of the most important features of Go programming are listed below −

- Support for environment adopting patterns similar to dynamic languages. For example, type inference (x := 0 is valid declaration of a variable x of type int)

- Compilation time is fast.

- Built-in concurrency support: lightweight processes (via go routines), channels, select statement.

- Go programs are simple, concise, and safe.

To make it easy for everyone to follow along, just head to https://repl.it/languages/go so you can code without installing anything.

To install Go on your machine, head to their main website: https://golang.org/dl/

If you'd like help installing Go or setting anything up, feel free to come up and ask questions after the talk!

I'll be going through some basic code examples to introduce common programming practices in Go.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello World")

}| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Boolean | True or False values |

| Numeric | Integers or floating point values |

| String | Immutable sequences of bytes |

| Derived | Pointer types, Array types, Struct types, Function types, etc. |

| Integer Types |

|---|

| uint8 |

| uint16 |

| uint32 |

| uint64 |

| int8 |

| int16 |

| int32 |

| int64 |

| Floating-Point Types |

|---|

| float32 |

| float64 |

| complex64 |

| complex128 |

| Other Numeric Types | Description |

|---|---|

| byte | same as uint8 |

| rune | same as int32 |

| uint | 32 or 64bit depending on system |

| int | 32 or 64bit depending on systme |

| uintptr | special type to consider pointer as a uint for easier arithmetic |

Here we see some different ways to initialize variables of different types

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var i, j int = 1, 2 // explicit type declaration

k := 3 // implicit type declaration

c, python, java := true, false, "no!" // mixed-type implicit declaration

fmt.Println(i, j, k, c, python, java)

}Additionally you can also get the type of a variable with %T format specifier

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var x float64

x = 20.0

fmt.Println(x)

fmt.Printf("x is of type %T\n", x)

}Here is an example of various types in Go being used, as well as demonstrating how you can use import() and var() to import various things and declare many variables without having to retype too much:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math/cmplx"

)

var (

ToBe bool = false

MaxInt uint64 = 1<<64 - 1

z complex128 = cmplx.Sqrt(-5 + 12i)

)

func main() {

fmt.Printf("Type: %T Value: %v\n", ToBe, ToBe)

fmt.Printf("Type: %T Value: %v\n", MaxInt, MaxInt)

fmt.Printf("Type: %T Value: %v\n", z, z)

}| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| + | Adds two operands |

| - | Subtracts second operand from first operand |

| * | Multiplies operands together |

| / | Divides first operand by second operand |

| % | Modulus operator - gives remainder of division |

| ++ | Increments value by 1 |

| -- | Decrements value by 1 |

| Operator |

|---|

| == |

| <= |

| >= |

| < |

| > |

| != |

| -- |

| Operator | Description |

|---|---|

| && | AND |

| || | OR |

| ! | NOT |

Find documentation on all operators here: https://www.tutorialspoint.com/go/go_operators.htm

Functions are similar to most other languages, one noticable difference being that the return type is at the end of the function header:

package main

import "fmt"

func add(x int, y int) int {

return x + y

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(add(42, 13))

}However, one neat trick is that if all parameters are of the same type, you can just put the type at the end of the parameters as seen below:

package main

import "fmt"

func add(x, y int) int {

return x + y

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(add(42, 13))

}You can also return multiple things in Go which you can't do in every language (without some workaround)

package main

import "fmt"

func swap(x, y string) (string, string) {

return y, x

}

func main() {

a, b := swap("hello", "world")

fmt.Println(a, b)

}Variables that are declared with no initial value are given a value of "zero" - depending on what that means for the given type. Here's some example default type values

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var (

i int

f float64

b bool

s string

)

fmt.Printf("%v %v %v %v\n", i, f, b, s)

}You can also cast variables to other types with type(var):

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func main() {

var x, y int = 3, 4

// Pythagorean Theorem: z = sqrt(x^2 + y^2)

var f float64 = math.Sqrt(float64(x*x + y*y))

var z uint = uint(f)

fmt.Println(x, y, z)

}Go only has one looping mechanism, the for loop. It doesn't

have while loops, but that's fine because any while loop can be

represented as a for loop anyways. Note you don't need parentheses

around the bounds of the for loop like you do in C/C++:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 0

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

sum += i

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}Also, the initial and post statements of the for loop are optional, and this is a useful way to replicate a while loop:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

sum := 1

for sum < 1000 {

sum += sum

}

fmt.Println(sum)

}To replicate an infinite loop while true:, you can just

have a for loop with no condition:

package main

func main() {

for {

}

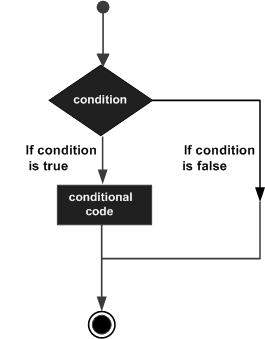

}If statements are useful to control the flow of your program. Like the for loops, you don't need any parentheses around the condition of the if statement. Here is an example of that for a sqrt() function that handles both real and complex numbers:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func sqrt(x float64) string {

if x < 0 {

return sqrt(-x) + "i"

}

else

{

return fmt.Sprint(math.Sqrt(x))

}

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(sqrt(2), sqrt(-4))

}How would I write a program that prints out the first 10 perfect squares (1 2 4 9 16 25 ... 100)?

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := ???; i < ???; ??? {

fmt.Println(???)

}

}How would I print out only the even numbers between 1 and 10 using an if statement? (2 4 6 8 10) (Hint: Modulo Operator)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := ???; i < ???; ??? {

if <i is even>??? {

fmt.Println(i)

}

}

}How would you print the even numbers between 1 and 10 with only a for loop and no if statement? (2 4 6 8 10)

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

for i := ???; i < ???; ??? {

fmt.Println(???)

}

}A defer statement defers the execution of a function until the surrounding function returns. DISCLAIMER: The value in the statement is captured where the statement occurs.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("world") // happens second because of defer statement

fmt.Println("hello") // happens first

}This could be useful in situations where you want to print values before and after certain cases since the value is captured at the time of the defer statement

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

x := 5

defer fmt.Println("Before:", x)

x = 10

defer fmt.Println("After:", x)

x = 15

fmt.Println("Here are the values of x throughout the program:")

}Like C, Go has Structs, but not Classes. A Struct is just a collection of fields/variables.

package main

import "fmt"

type Coordinate struct {

X int

Y int

}

func main() {

point := Coordinate{1, 2} // Initializes X -> 1 and Y -> 2

fmt.Println("X:", point.X)

fmt.Println("Y:", point.Y)

}To declare an array of type T in Go, you just write [size]T where size

is how big you want the array to be.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var a [2]string

a[0] = "Hello"

a[1] = "World"

fmt.Println(a[0], a[1])

fmt.Println(a)

primes := [6]int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13}

fmt.Println(primes)

}A slice does not store any data, it just describes a section of an underlying array. Changing the elements of a slice modifies the corresponding elements of its underlying array.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

primes := [6]int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13}

var s []int = primes[1:4] // [start, end)

fmt.Println(s) // begin index inclusive, end index exclusive

}If you define everything in an array when you initialize it, and don't specify a size - it creates a slice that references that array

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

array := [6]int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13}

slice := []int{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13}

fmt.Printf("%T\n", array)

fmt.Printf("%T\n", slice)

}Slices can be created with the built-in make function:

allowing you to create dynamically-sized arrays of a

specified size.

The make function allocates a zeroed-out array and

returns a slice that refers to that array

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := make([]int, 5) // len = 5

printSlice("a", a)

b := make([]int, 0, 5) // len = 0, cap = 5

printSlice("b", b)

// Capacity == Total allocated size

// Length == Total used size

}

func printSlice(s string, x []int) {

fmt.Printf("%s len=%d cap=%d %v\n",

s, len(x), cap(x), x)

}In order for the dynamic array to be useful, we need some way

to add elements to it whenever we want. That's where the append

function comes in. append adds an item to the end of the

slice, just like in Python:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

var s []int // SAME AS s := make([]int, 0)

printSlice(s)

// append works on nil slices.

s = append(s, 0) // can append values to increase size

printSlice(s)

// We can add more than one element at a time.

s = append(s, 1, 2, 3)

printSlice(s)

}

func printSlice(s []int) {

fmt.Printf("len=%d cap=%d %v\n", len(s), cap(s), s)

}Go has a built-in range function, similar to the range function

in Python, but actually closer to the enumerate function in Python

because it returns both the index and the element!

This range function makes it easy to iterate over things like Slices

much more elegantly:

package main

import "fmt"

var pow = []int{1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128}

func main() {

for i, v := range pow {

fmt.Printf("2**%d = %d\n", i, v)

}

}Optionally, you can drop the index or drop the value depending on your needs:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

// Omitting value: just don't include it

pow := make([]int, 10)

for i := range pow {

pow[i] = 1 << uint(i) // == 2**i

}

// Omitting index: Use '_' which compiler accepts when not used

for _, value := range pow {

fmt.Printf("%d\n", value)

}

}Very similar to Dictionaries in Python / Maps in C such that they contain (key, value) pairs

package main

import "fmt"

type Coordinate struct {

Lat, Long float64

}

var m = map[string]Coordinate{

"Bell Labs": Coordinate{

40.68433, -74.39967,

},

"Google": Coordinate{

37.42202, -122.08408,

},

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(m)

}Dynamically-sized Maps can also be created with the make keyword

They also have a delete method to remove (key,value) pairs, as well

as the ability to check whether or not elements exist in a map

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

m := make(map[string]int) // create empty map

m["Answer"] = 42 // add (key, value) pair ("Answer", 42) to map

fmt.Println("The value:", m["Answer"])

v, ok := m["Answer"]

fmt.Println("The value:", v, "Present?", ok)

delete(m, "Answer")

v, ok = m["Answer"]

fmt.Println("The value:", v, "Present?", ok)

}Functions can be passed around the same way that values and variables can. For example, you can have a function that takes in another function as a parameter:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"math"

)

func compute(fn func(float64, float64) float64) float64 {

return fn(3, 4)

}

func main() {

hypot := func(x, y float64) float64 {

return math.Sqrt(x*x + y*y)

}

fmt.Println(hypot(5, 12))

fmt.Println(compute(hypot))

fmt.Println(compute(math.Pow))

}A goroutine is a lightweight thread managed by the Go runtime

- Like pthreads in C/C++

go f(x, y, z)starts a new goroutine (thread) that is running

f(x, y, z)Here is an example showing that a goroutine is running concurrently (at the same time) with the main program

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func say(s string) {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println(s)

}

}

func main() {

go say("world")

say("hello")

}But since the goroutines (threads) are running at the same time, things can get messy when they try to access the same thing, because you don't know in what order it will happen - like the print statements above

Go has a type called "Channel" which are pipes that connect concurrent

go routines. You can send values into a channel from one routine

and receive that value from the channel in another routine with the channel

operator <-.

Channels have to be created with the make keyword

By default, sends and receives block until the other side is ready. This allows goroutines to synchronize without explicit locks or condition variables. - Easy Concurrency!

package main

import "fmt"

func sum(s []int, c chan int) {

sum := 0 // implicit declaration of int sum to 0

for _, v := range s { // iterate through array passed into function

sum += v // add values in array to total sum

}

c <- sum // send sum to channel c

}

func main() {

s := []int{7, 2, 8, -9, 4, 0}

c := make(chan int) // Create channel that holds ints

// 'go' keyword starts new go-routine on the function that comes after

go sum(s[:len(s)/2], c) // One routine sum up first half

go sum(s[len(s)/2:], c) // Second routine sum up second half

x, y := <-c, <-c // receive from c

fmt.Println(x, y, x+y)

}By default the goroutine communication is synchronous and unbuffered: sends do not complete until there is a receiver to accept the value. There must be a receiver ready to receive data from the channel and then the sender can hand it over directly to the receiver.

package main

import "fmt"

func sendToChannel(c chan int) {

c <- 1

c <- 2

}

func main() {

c := make(chan int) // Create channel that holds ints

go sendToChannel(c) // Without 'go', this program would fail

x, y := <-c, <-c

fmt.Println(x, y)

}