Git as a Package Registry

Anyone who has worked in the NPM ecosystem will know how painful it can be when you have two closely related libraries that you wish to update together. You update the first, run your tests and make a release to NPM. Now you update the second, but oh look, a bug! So you return to the first, fix the code, push to NPM...

Or imagine your company has strict requirements about how you can store your code. You cannot release your packages openly on GitHub, and using a hosted binary repository requires you to map your current security policy into their system. Not to mention that it also introduces another point-of-failure.

Or consider how an NPM package might differ from the source-code reviewed on GitHub. Have you ever checked the hash of an NPM package against the output of npm publish run locally? I found a mismatch on the first try; it was just a timestamp difference, but it's impractical to investigate every one.

All of these problems are solved if you use Git as your package registry.

- Infrastructure - You already have a Git server

- Security - Git is already configured with your team's SSH keys

- Integrity - you can control exactly what goes into source-control

In other words, things become much simpler if we do not have a package registry at all, but instead leverage existing source-control to achieve the same ends.

Following the design of Go Dep, we can consider how a Git repository might map to package versions:

- Every commit is a version.

- Every branch is a collection of versions, namely the commits on that branch.

- Every tag is a version; it is the commit that it points to.

- Every tag that a satisfies a sem-ver parser is a sem-ver.

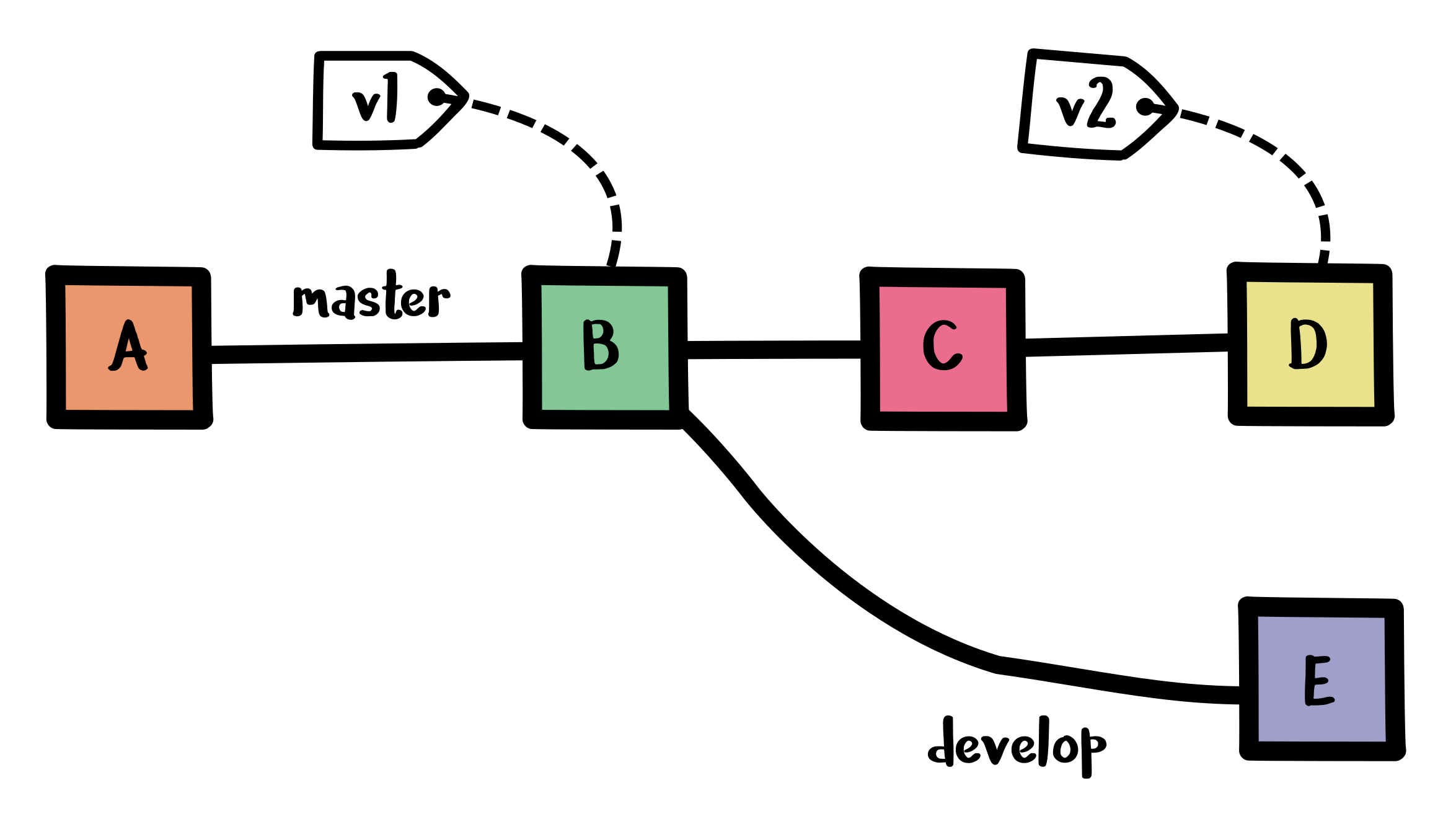

A picture is worth a 1000 words, so consider this Git commit graph:

We have the following versions:

- Commit

Ais on branchmasterand branchdevelop - Commit

Bis on branchmaster, branchdevelop, tagv1and sem-verv1.0.0 - Commit

Cis on branchmaster - Commit

Dis on branchmaster, tagv2and sem-verv2.0.0 - Commit

Eis on branchdevelop

Now the user can write requirements against this information.

-

I might ask for any version on

develop, which would beA,BorE. -

Or perhaps any sem-ver

>1, which would beDatv2.0.0. -

We might even combine these requirements. Requiring a commit that is on

masteranddevelopwould give usAandB.

We do not need a package registry to obtain version information, we can pull it directly from Git.

Names are the final piece of the puzzle. How do we know which package names (e.g. boostorg/math) correspond to which Git URLs (e.g. https://github.com/boostorg/math.git)?

Buckaroo supports namespace discovery as it explores the dependency graph, but that's another topic entirely! For most cases, we already have a namespace, provided by the usual suspects...

The mapping is quite simple. Every package on these hosted Git platforms has an owner and a project name. These can be mapped either to an SSH or HTTP Git URL:

let gitHubHttp owner project =

"https://github.com/" + owner + "/" + project + ".git"

let gitHubSsh owner project =

"git@github.com:" + owner + "/" + project + ".git"This is how Buckaroo works without a package registry; it extracts the information straight from source-control.