This is where I'll post everything I have learned about C++ from Learn Cpp. Various other sources will also be used such as:

- Tutorials Point

- Simplilearn

- Programmiz - this is a great resource because it has several example program files and various others.

Preprocessor TODO

Typical structure:

- Header files - e.g.

add.h-

extension

.h(sometimes.hpp). -

generally should not contain function and variable definitions.

-

it should include forward delcarations of the functions (just the name and args).

-

use

<>for referencing headers that come with the compiler likeiostream, otherwise use"". -

Each file should explicitly #include all of the header files it needs to compile. Do not rely on headers included transitively from other headers.

-

Use header guards to avoid namespace collision:

#ifndef SOME_UNIQUE_NAME_HERE #define SOME_UNIQUE_NAME_HERE // your declarations (and certain types of definitions) here #endif

Or you can use

# pragma oncebut this is not supported by all compilers. -

tips

- each header file should have a specific job & be as independent as possible.

- it should #include all the dependencies

-

- Function (source) files - e.g.

add.cpp- extension

.cpp. - needs to include its paired header, such as

#include "add.h". - typically defines a function.

- do not #include .cpp files.

- extension

main.cppfile- Calls all the other scripts

- needs an

#include "add.h"The compiler compiles each file individually - it does not check each file against others.

Statements(line of code) and expressions (combination of symbols to be evaluated) are concluded by ;.

Identifier: a unique name for a varible, class, function etc.

The entry point of a program is:

int main()

{

// some code

return 0; ## the STATUS code for our program (0 = successful exit)

}There are varous ways of initialising variables:

int a;

int b = 5;

int d{7};You must declare the type: one of int, float,double,bool, char.

Variables can be declared without being initialised.

Variables can be initalised with expressions and function calls e.g. int i { add(a,b) };.

- Get user input with

std::cine.g. take in 2 numbers from the user withstd::cin >> x >> y. - Printing output to the screen: use

std::cout << "hello";.

- Rule of 3 / D.R.Y. (Do not repeat yourself) i.e. if you write the same piece of code more than 3 times, then write a function.

- Functions cannpt be defined within functions in C++ - i.e. not in

main()

Functions are defined as:

<return type> <function name>(<arguments>){

// code

}

// e.g. A function to add 2 integers

int add(int a, int b){

return a + b; // because of the way C++ scopes these are only visible to the function

}- If a function does not return anything then the return type is

void. - n.b. Refactoring is the process of splitting a long function into multiple sub functions.

- Functions can be declared before they are defined - this is called forward declaration. This tells the compiler about the existence of an identifier

int add(int x, int y); // declare before definitionWe use can use forward declarations in the top of the main.cpp script so that the compiler knows that a function is defined somewhere else.

E.g. the same function name/identifier is used across multiple files, but the functions have different definitions. This will cause a linker error. Namespace(s) are a region that allows you to declare names inside of it for the the purpose of avoiding collisions. Any name not defined inside a class,function or namespace is considerd part of the global namespace.

// namespace contents are accessed with: the `::` operator

std::coutNamespaces can also be activated using a directive: using namespace std which tells the compile to check the std namespace when looking for identifiers with no prefix. But this is not recommeneded.

This tells the preprocessor to include the contents of another file, such as #include <iostream> or `#include.

#define MY_NAME "Louis" this defines a variable called MY_NAME, in the global namespace, with value "Louis".

Like any variable it doesnt have to be initialised.

We can use these for debugging purposes.

#ifndef VARIABLE

// this code will not be run if VARIABLE has not been defined

#endif

#if 0

// this code will not be run

#end ifsee website

Different integer types have different sizes in bytes.

There are special NaN and inf types: nan,posinf,neginf.

If we divide integers this will carry out integer division - 8/5 = 1

Best practices for int:

- Prefer

intwhen the size of the integer doesn't matter (e.g. the number will always fit within the range of a 2-byte signed integer). - Prefer

std::int#_twhen storing a quantity that needs a guaranteed range. - Prefer

std::uint#_twhen doing bit manipulation or where well-defined wrap-around behavior is required. Tips forfloat: - floats are useful for storing either very large or very small numbers.

std::setprecision()allows us to set the number of digits we want a floating point number to show.- Favour

doubleoverfloatbecause the lack of precision in float can lead to inaccuracies.

- Rounding error - when a number cannot be adequately represented by a finite number of binary digits (e.g 0.1 is represented as 0.100000000000001).

- integer overflow - when a number is too large to be stored in the specfied data type. This causes integers to wrap around. Booleans:

- set the value as either

trueorfalse.bool b1 {true}.

- if statement:

if (statement1){

//***

} else if (statement2) {

//***

} else {

//***

}it can also be written without blocks:

if (age >= 21) purchaseBeer()

- while loop:

while (condition)

{

if (....)

{

// do something

// update condition

}

}- switch statement:

Because all the statements that are satisfied (TRUE) are executed a

breakstatement should be used, as well as adefault statement.

switch(expression) {

case x:

// code block

break;

case y:

// code block

break;

default:

// code block

}- do while statement: A do while statement is a looping construct that works just like a while loop, except the statement always executes at least once. After the statement has been executed, the do-while loop checks the condition. If the condition evaluates to true, the path of execution jumps back to the top of the do-while loop and executes it again.

do

{

// this will be executed right away and again if the while condition is met.

}

while (condition)

{

// some code

}- for statement:

for (int x = 0 ; x < 10 ; ++x )

{

//code to loop through

}

// You can also loop over multiple variables

for (int x=0, y=0; x <=100 ; ++x, --y)

{

// do something with two variables x, y

}how to intialise a char char ch1{ 'a' } but you cannot initialise multiple chars at once (e.g. abc).

we can use the command static_cast<type>(variable) to convert between types. E.g. static_cast<int>(5.5) will return 5.

This is especially useful for converting from signed to unsigned and vice versa.

strings arent a fundamental data type - they are a compound type declared in the C standard library.

std::string myName {"Louis"}; //initialise a string as such.To enter a full line of text use something like std::getline() with std::ws(). The latter tells std::cin to ignore any leading whitespace.

std::cout << "Enter your age: ";

std::string age{};

std::getline(std::cin >> std::ws, age); The length of a string can be determined with: STRING.length()

Also note that std::string::length() returns an unsigned integral value (most likely size_t). If you want to assign the length to an int variable, you should static_cast it to avoid compiler warnings about signed/unsigned conversions:

int length = static_cast<int>(myName.length());A constant is a fixed value that may not be changed.

Literal constants are unamed values inserted directly into the code - like the number 5 or 6e3.

Constants can be intialised with the const keyword.

such as:

// const values must be initialised

const double gravity = 9.98;constexpr means the constant must be determined at compile time. It is best practice to use this.

| Operator | Description |

| ------------------- | -------------------- |

| `%` | |

| `++` | |

| `--` | |

| `&` | |

| `*` | |

| `*=` | |

| `/=` | |

| `%=` | |

| `+=` and `-=` | |

| `?:` | |

| `new` | |

| `delete` | |

| `&&` or `&` | |

| `||` or `|` | |

| `^` | |

| `!=` | |

We need the cmath library.

#include <cmath>

double x {std::Pow(3,4) // this gives 3^{4} }A side effect occurs if the code does anything/affects anything after the expression/function has ended.

++x will modify x everywhere whereas x++ will not.

Due to arithmetic errors we should compare floating point values using: std::abs(a - b) <= epsilon which is found in the <cmath> header

In the majority of cases, this is fine -- we're usually not so hard-up for memory that we need to care about 7 wasted bits (we’re better off optimizing for understandability and maintainability). However, in some storage-intensive cases, it can be useful to "pack" 8 individual Boolean values into a single byte for storage efficiency purposes.

Doing these things requires that we can manipulate objects at the bit level. Fortunately, C++ gives us tools to do precisely this. Modifying individual bits within an object is called bit manipulation.

Bit manipulation is also useful in encryption and compression algorithms. See Bitwise manipulation.

Define namespaces with

namespace foo // this is the name of my namespace

{

int add(int x, int y)

{

return x + y;

}

}

// Call it with

foo::add(1,2)- Variables are local to blocks

{ ..... }, they will no longer exist after the code in blocks is executed. Hence these are called local variables. - Global variables can be defined outside the function but can not automatically be be accessed anywhere in the file. See below for information about linkage. sometimes th prefix "g_" is used to indicate that a variable is global.

-

Internal linkage

- An identifier with internal linkage can be seen and used within a single file, but it is not accessible from other files.

- To make a non-constant global variable internal, we use the

statickeyword. - The static keyword can also allow local variables to persist out of scope.

- const global variables have internal linkage by default.

-

External linkage

- In lesson 2.7 -- Programs with multiple code files, you learned that you can call a function defined in one file from another file. This is because functions have external linkage by default.

- In order to call a function defined in another file, you must

place a forward declaration for the function in any other files wishing to use the function. - The forward declaration tells the compiler about the existence of the function, and the linker connects the function calls to the actual function definition.

- We can do the same thing with external variables.

- The keyword

extern1, will create external linkage.

We could define a variable in another file such as:

constants.h

#ifndef CONSTANTS_H #define CONSTANTS_H namespace constants { // since the actual variables are inside a namespace, the forward declarations need to be inside a namespace as well extern const double pi; extern const double avogadro; extern const double myGravity; } #endif

constants.cpp.

#include "constants.h" namespace constants { // actual global variables extern const double pi { 3.14159 }; extern const double avogadro { 6.0221413e23 }; extern const double myGravity { 9.2 }; // m/s^2 -- gravity is light on this planet }

main.cpp

#include <iostream> extern int g_x; // this extern is a forward declaration of a variable named g_x that is defined somewhere else extern const int g_y; // this extern is a forward declaration of a const variable named g_y that is defined somewhere else int main() { std::cout << g_x; // prints 2 return 0; }

| Category | Description |

| -------------------- | ----------------------- |

| conditional | |

| halts | |

| loops | |

| halts | |

| Exceptions | |

- A

breakstatement terminates the switch or loop, and execution continues at the first statement beyond the switch or loop. - The

continuestatement provides a convenient way to end the current iteration of a loop without terminating the entire loop. std::exit(0);This will cause the program to exit normally with status code 0.- The

std::abort()function causes your program to terminate abnormally. This won't do any cleanup.

- Just use an if (or switch) statement to handle errors

- When the user enters input in response to an extraction operation, that data is placed in a buffer inside of std::cin.

- A buffer (also called a data buffer) is simply a piece of memory set aside for storing data temporarily while it’s moved from one place to another. In this case, the buffer is used to hold user input while it’s waiting to be extracted to variables.

- To ignore everything up to and including the next ‘\n’ character, we call

std::cin.ignore(std::numeric_limits<std::streamsize>::max(), '\n'); - More can be found out about handling invalid user input.

- An assertion is an expression that will be true unless there is a bug in the program. If the expression evaluates to true, the assertion statement does nothing. If the conditional expression evaluates to false, an error message is displayed and the program is terminated (via std::abort).

- This error message typically contains the expression that failed as text, along with the name of the code file and the line number of the assertion.

- Need to include

#include <cassert> // for assert() - call it with

assert(condition && "Need to handle case where student was just moved to another classroom"); - We can also use

static_assert(sizeof(long) == 8, "long must be 8 bytes");

We can use the Mersenne Twister algorithm

#include <iostream>

#include <random> // for std::mt19937

int main()

{

std::mt19937 mt; // Instantiate a 32-bit Mersenne Twister

// Print a bunch of random numbers

for (int count{ 1 }; count <= 40; ++count)

{

std::cout << mt() << '\t'; // generate a random number

// If we've printed 5 numbers, start a new row

if (count % 5 == 0)

std::cout << '\n';

}

return 0;

}- Aliases (names) for an existing data type can be created with the

usingkeyword such as inusing distance_t = double; typedefalso accomplishes this, e.g.typedef long miles_t- Aliases like this can be useful for the purpose of code readability.

- It can also make long complex types easier to deal with.

using pairlist_t = std::vector<std::pair<std::string, int>>;

- The

autokeyword automatically infers the type. - This can be applied to variables or to functions.

Function overloading allows us to create multiple functions with the same name, so long as each identically named function has different parameters (or the functions can be otherwise differentiated). E.g.

int add(int x, int y) // integer version

{

return x + y;

}

double add(double x, double y) // floating point version

{

return x + y;

}This means there are different number of arguments or argument types.

Ex. void print(int x, int y=4)

This is an alternative to function overloading and allows us to create a function template when we want to use inputs with different input and output types.

// template for the max class

// the arguments and returns will be of type T.

template <typename T>

T max(T x, T y)

{

return (x > y) ? x : y; //ternary operator

}

// to instantiate this (and call it) we need to do

max<int>(1,2)NOTE you have to be careful about defining template helper functions in other files.

TODO

- A reference is an alias for an existing object. Once a reference has been defined, any operation on the reference is applied to the object being referenced.

- A reference is essentially identical to the object being referenced.

- References can be created with the

&operator, placed next to the type.

int // a normal int type

int& // an lvalue reference to an int object

double& // an lvalue reference to a double object

int x { 5 }; // x is a normal integer variable

int& ref { x }; // ref is an lvalue reference variable that can now be used as an alias for variable x

to change the value of the original object just call it like so:

ref = 6; - Once initialized, a reference in C++ cannot be reseated, meaning it cannot be changed to reference another object.

- Refs are not suitable for

const.

- When passing by value the object is copied into the function, which is expensive for objects like std::string.

- passing by reference avoids making expesnive copies

- THis is done by

<return> <function>(<type>& arg). For example

void foo(int a, char& b, const std::string& c)

{

c[a] = b; // modify the string c which will modify the original string

std::cout << c;

}-

Operators:

&x(not likeint& x) is the address-of operator.- The address-of operator (&) returns the memory address of its operand. e.g. printing

&xreturns 0027FEA0. - the dereference operator

*returns the value at given memory address. E.g.std::cout << *(&X)returns the value stored by x.

-

A pointer is an object that holds a memory address (typically of another variable) as its value.

-

pointers are initialised using the

*operator after the type such asint* ptrwhich initialises a pointer to an integer. -

int* ptr{ &x }this pointer variable holds the adddress of x -

We can change what the pointer points to by assigning it to the address of another variable.

// Initialise a pointer that points to the integer x

int x{ 5 };

int* ptr{ &x };

// We can reassign the pointer

int y{ 6 };

ptr = &y; // // change ptr to point at y

// Access the stored value

std::cout << *ptr;- Const pointers cannot be changed after initilisation.

- NOTE A pointer should either hold the address of a valid object, or be set to nullptr. That way we only need to test pointers for null, and can assume any non-null pointer is valid.

- We can initialise null pointers with:

int* ptr {};orint* ptr { nullptr };ordouble* ptr { NULL };. - We can check to see if a pointer is a null pointer, with

if (ptr), as it is automatically converted to a boolean (True). - Favor references over pointers unless the additional capabilities provided by pointers are needed.

To do this we specify the function argument as a pointer e.g.

void print(int* ptr)

{

if (ptr) // if ptr is not a null pointer

{

std::cout << *ptr;

}

}(Just like we can pass a normal variable by reference, we can also pass pointers by reference)[https://www.learncpp.com/cpp-tutorial/pass-by-address-part-2/].

Pass by address vs pass by reference: Prefer pass by reference to pass by address unless you have a specific reason to use pass by address.

In previous lessons, we discussed that when passing an argument by value, a copy of the argument is made into the function parameter. For fundamental types (which are cheap to copy), this is fine. But copying is typically expensive for class types (such as std::string).

Notes:

- We can avoid making an expensive copy by utilizing passing by (const) reference (or pass by address) instead.

const std::string& getProgramName() {// function code}- Return by address works almost identically to return by reference, except a pointer to an object is returned instead of a reference to an object. Return by address has the same primary caveat as return by reference -- the object being returned by address must outlive the scope of the function returning the address, otherwise the caller will receive a dangling pointer.

- wild pointers are pointers yet to be initalised but dangling pointers are for pointers that refer to objects that hare no longer valid.

- The major advantage of return by address over return by reference is that we can have the function return nullptr if there is no valid object to return.

We can define our own types, below is the user defined type defined in the header file:

Fraction.h

#ifndef FRACTION_H

#define FRACTION_H

// Define a new type named Fraction

// This only defines what a Fraction looks like, it doesn't create one

// Note that this is a full definition, not a forward declaration

struct Fraction

{

int numerator {};

int denominator {};

};

#endifWe can initialise this with something like: Fraction frac{ 3, 4 }; which creates a fraction type frac

- An enumeration (also called an enumerated type or an enum) is a compound data type where every possible value is defined as a symbolic constant (called an enumerator).

- They are initialised with the keyword

enum. - Enums or enumerations are generally used when you expect the variable to select one value from the possible set of values.

- It increases the abstraction and enables you to focus more on values rather than worrying about how to store them. It is also helpful for code documentation and readability purposes.

- create a new data type that has a fixed range of possible values.

- They are defined in the global scope.

- They are implicitly converted to integral values.

- Something like

print(red)could return an int. - Another example of this could be

red + 5will give an intergal value.

- Something like

- Scoped enums are declared with

enum Class <NAME>and we can access enum names with the::operator. - Prefer scoped enums over unscoped enums.

- Scoped enums are not implicitly converted to integers.

The compiler and commands like cin don't explicitly know how to interpret inputs when dealing with enums.

int main()

{

std::cout << "Enter a pet (0=cat, 1=dog, 2=pig, 3=whale): ";

int input{};

std::cin >> input; // input an integer

Pet pet{ static_cast<Pet>(input) }; // static_cast our integer to a Pet

return 0;

}- structs are a collection of variables of different data types under a single name.

- It is created with the

structkeyword. - It is similar to a class. The struct is only a blueprint for creating variables and needs to be initialised.

- struct members are accessed with the

.operator. - Structs can have members of different types.

Structs can have the values assigned initally or be assigned with a list of sorts.

// struct definition

struct Employee

{

int id{}

double wage{}

}

// Instantiate struct

Employee joe {1, 60000.0}

// update single value

Employee joe {joe.id, 70000.0}- Structs can be passed in by reference and address and the

.can be used. - If we make a pointer to a struct

Employee* ptr{ &joe }whereptris the pointer of type 'Employee' pointing to the address of the structjoe. - We can access the member with the

->operator or by dereferencing(*ptr).id.- e.g.

ptr -> id.

- e.g.

Arrays can be sorted with

std::sort which lives in the <algorithm> header.

- It can be thought of as a special datatype that lets us safely view (ie. without modification) a string defined elsewhere - whereas

std::stringcopies the string. - This lives in the

<string_view>header. - It has the same functions, such as:

.remove_suffix.remove_prefix- ``

- It is important not to modify a string during its runtime.

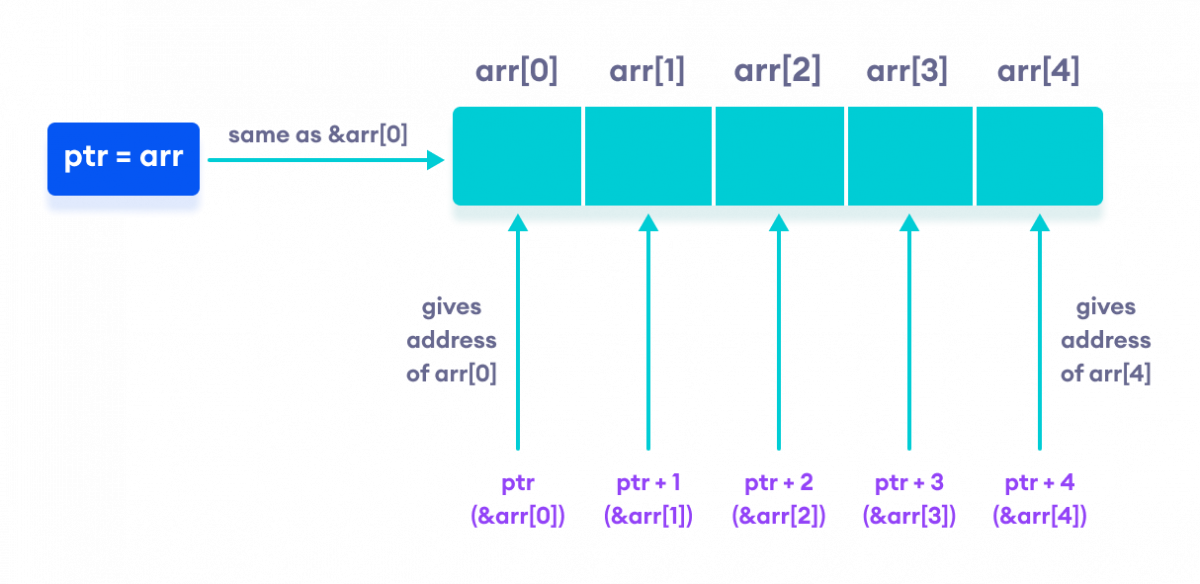

- C++ allows us to perform integer additon with pointers e.g.

ptr + 5. - This allows us to access consecutive elements of arrays:

*(array + n) is equal to array[n].[]Is actually pointer arithmetic under the hood! - Functions like

std::beginandstd::endfrom the<iterators>header return a pointer to the first and last elements of an array. - Another useful example is the

std::countif(std::begin(<array>), std::end(<array>), <function_name>)function. This counts the number of measurements that meet a condition.

Dangling pointers can occur if:

- Pointers go out of scope, e.g. declared and not deleted in a function call.

- Assigned a new value before

Solution: only assign to a pointer once, and always use delete.

In the case of arrays we should use delete[].

- Declaring a dynamic 1D array:

int* array{ new int[length]{} };orint* array = new int[5].

Declaring a 2D array:

A standard 2D array would be declared like int array[10][20].

We declare a dynamic M x N array with int** array = new int*[M] This creates a pointer to a pointer of size M.

array points to each row (which is an object with several columns).

// For each pointer (referring to a row)

// allocate memory for several columns.

for(int i = 0; i < rowCount; ++i)

a[i] = new int[colCount];

We must also use a loop to delete[] each row array individually.

These are of the form for (<type> <element> : <array>) {...}.

There are several variations of this:

// some numbers to iterate over

int Fibonacci[] {1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21}

// for-each loop with auto kw

for (auto number : Fibonacci){

std::cout << number

}

// To avoid copying each array element (which is expensive) use references

for (auto& element : Fibonacci){

std::cout << element

}Note that if we are only using elements in a read only way its best to use const

This can point to objects of any data type!

It is initiaised with void* ptr; and can point to anything - like a struct, int float etc...

BUT dereferencing is illegal so the pointer must be cast to a different type.

int* intPtr{ static_cast<int*>(voidPtr) }

Generally these should be avoided but they are neat!

- defined in the

<array>header - defines a fixed array functionality

- declared with

std::array<int, 3> myArray; - you can also do

std::array myArray {1,2,3} - it can be indexed with ``[]

or.at()` which also does bounds checking. - length can be found with

.size() - aggregate type so we can store multiple types in it.

- Example: creating an array of string types

std::array<std::string_view, 5> arr{ "apple", "banana", "walnut", "lemon", "peanut" };

- lives in the

<vector>header - don't have to use

newordelete - declaration is simple - no need to specify length - we just need the type of each element.

std::vector<int> array;std::vector<int> array2 {1,2,3}

- We can howwever created a fixed size vector (e.g. of size 5)

std::vector<int> array(5); - Can be indexed with

[]and.at() - It has its own memory management system - it automatically deallocates the memory when it goes out of scope.

- length can be found with

.size(). - values can be inserted with

.push_back()or removed withpop_back()or.erase()which takes the position. - It can also be resized with

.resizewhich will allocate more elements with 0 entries (default value for the type). This is very computationally expensive so try to avoid it!

vector<vector<int>> v {{1, 0, 1}, {0, 1}, {1, 0, 1}};see- This initialises the matrix

v: 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1

- This initialises the matrix

vector<vector<>>means we are creating a vector for which each element is a vector- we can access elements with

v[i][j]. - Example: removing a row using iterators

// Iterator for the 2-D vector vector<vector<int>>::iterator it = v.begin(); // Remove the second vector from a 2-D vector v.erase(it + 1);

An iterator is an object designed to traverse through a container, providing access to each element along the way.

Examples:

- array - this container might offer a forwards iterator, that walks through the array in a forwards order.

- Pointers are iterators - they traverse data stored sequentially.

std::begin()andstd::end().

There are 3 categories: <algorithm> more details

- Inspectors - view but not modify data in container (e.g. searching and counting)

std::find()

- Mutators - modify data in container (e.g. sorting/shuffling)

std::sort()- Examples:

std::sort(arr.begin(), arr.end())- sort in ascending order.std::sort(arr.begin(), arr.end(), greater);- call our custom greater function- [A custom sorting function example (great example shows the use of callable's)]

- Facilitators - used to generate results from each value in data

std::for_each()

void doubleNumber(int& i) { i *= 2; } std::for_each(arr.begin(), arr.end(), doubleNumber); // pass a function by reference

int foo(int x) { return x; }

// We can treate function pointers like variables

int (*fcnPtr)(int){ &foo }; // Initialize fcnPtr with function foo

(*fcnPtr)(5); // call function foo(5) through fcnPtr.

// call this in another function

void selectionSort(int* array, int size, bool (*comparisonFcn)(int, int))

// It is also convenient to use an alias for this function pointer e.g.

using ValidateFunction = bool(*)(int, int);

bool validate(int x, int y, ValidateFunction pfcn);We can even use the std::function as an alternate method of defining and storing function pointers

#include <functional>

bool validate(int x, int y, std::function<bool(int, int)> fcn);

- Prefer memoisation over plain recursion, to limit the number of function calls and memory allocated on the stack/heap.

- Prefer iteration over recursion, where possible.

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

-

argc is an integer parameter containing a count of the number of arguments passed to the program (think: argc = argument count). argc will always be at least 1, because the first argument is always the name of the program itself. Each command line argument the user provides will cause argc to increase by 1.

-

argv is where the actual argument values are stored (think: argv = argument values, though the proper name is “argument vectors”). Although the declaration of argv looks intimidating, argv is really just an array of C-style strings. The length of this array is argc.

- Uses the

...argument. - No type checking

- First, if possible, do not use ellipsis at all!

- Why ellipsis are dangerous: ellipsis don’t know how many parameters were passed

- length parameter

- Use a sentinel value - a sentinel is a special value that is used to terminate a loop when it is encountered. For example, with strings, the null terminator is used as a sentinel value to denote the end of the string.

- Use a decoder string - “decoder string” tells the program how to interpret the parameters.

- Ellipses:

double findAverage(int count, ...)

{

int sum{ 0 };

// We access the ellipsis through a va_list, so let's declare one

std::va_list list;

// We initialize the va_list using va_start. The first parameter is

// the list to initialize. The second parameter is the last non-ellipsis

// parameter.

va_start(list, count);

// Loop through all the ellipsis arguments

for (int arg{ 0 }; arg < count; ++arg)

{

// We use va_arg to get parameters out of our ellipsis

// The first parameter is the va_list we're using

// The second parameter is the type of the parameter

sum += va_arg(list, int);

}

// Cleanup the va_list when we're done.

va_end(list);

return static_cast<double>(sum) / count;

}- Not only do the ellipsis throw away the type of the parameters, it also throws away the number of parameters in the ellipsis. This means we have to devise our own solution for keeping track of the number of parameters passed into the ellipsis. Typically, this is done in one of three ways.