http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-2/peer-reviewed-papers/hacklabs-and-hackerspaces/

· Hacklabs y hackerspaces - rastreando dos genealogías

Hacklabs and hackerspaces – tracing two genealogies

Maxigas

- Introducción

Parece muy prometedor trazar la genealogía de los hackerspaces desde el punto de vista de los hacklabs, ya que la relación entre estas escenas raramente es discutida y en gran parte permanece inexplorada. Una aproximación metódica a dicha relación, echará luz a muchas diferencias y conexiones interesantes que pueden ser útiles para las profesionales que busquen nutrir y esparcir la cultura de los hackerspaces, como para académicas que buscan conceptualizarlo y entenderlo. En particular, los hackerspaces han mostrado ser un fenómeno viral que puede haber llegado al tope de su popularidad, y mientras una nueva ola de fablabs florece, gente como Grenzfurthner y Schneider (2009) han comenzado a preguntarse sobre la dirección de estos movimientos. Me gustaría contribuir a este debate, sobre la dirección política y los potenciales políticos de los hacklabs y hackerspaces, con un paper historiográfico comparativo y crítico. Mi interés principal es en cómo estas redes entrelazadas de instituciones y comunidades pueden escapar al aparato de captura capitalista, y como estas potencialidades están condicionadas por un arraigo histórico en varias escenas e historias.

It seems very promising to chart the genealogy of hackerspaces from the point of view of hacklabs, since the relationship between these scenes have seldom been discussed and largely remains unreflected.A methodological examination will highlight many interesting differences and connections that can be useful for practitioners who seek to foster and spread the hackerspace culture, as well as for academics who seek to conceptualise and understand it. In particular, hackerspaces proved to be a viral phenomenon which may have reached the height of its popularity, and while a new wave of fablabs spring up, people like Grenzfurthner and Schneider (2009) have started asking questions about the direction of these movements. I would like to contribute to this debate about the political direction and the political potentials of hacklabs and hackerspaces with a comparative, critical, historiographical paper. I am mostly interested in how these intertwined networks of institutions and communities can escape the the capitalist apparatus of capture, and how these potentialities are conditioned by a historical embeddedness in various scenes and histories.

Los hacklabs tienen algunas de las características de los hackerspaces, y, de hecho, muchas comunidades que están registradas en hackerspaces.org también se identifican como "hacklabs". Incluso algunos de los grupos registrados no serían considerados como hackerspaces "reales" por la mayoría de los demás. De hecho, hay un amplio espectro de términos y lugares parecidos de familia, como son los "espacios de coworking", "laboratorios de innovación", "media labs", "fab labs", "makerspaces", entre otros. No todos están basados siquiera en una comunidad, sino que han sido fundados por actores del sistema educativo formal o el sector comercial. Es imposible clarificar todo en un artículo corto. Por lo tanto sólo consideraré aquí hacklabs y hackerspaces comunitarios.

Hacklabs manifest some of the same traits as hackerspaces, and, indeed, many communities who are registered on hackerspaces.org identify themselves as “hacklabs” as well. Furthermore, some registered groups would not be considered to be a “real” hackerspace by most of the others. In fact, there is a rich spectrum of terms and places with a family resemblance such as “coworking spaces”, “innovation laboratories”, “media labs”, “fab labs”, “makerspaces”, and so on. Not all of these are even based on an existing community, but have been founded by actors of the formal educational system or commercial sector. It is impossible to clarify everything in the scope of a short article. I will therefore only consider community-led hacklabs and hackerspaces here.

A pesar del hecho de que estos espacios comparten una misma herencia cultural, algunas de sus raíces históricas e ideológicas son diferentes. Esto resulta en una adopción un poco distinta de las tecnologías y una sutil divergencia en sus modelos organizacionales. Históricamente hablando, los hacklabs comenzaron a mediados de los 90' y se popularizaron a mediados de los 2000'. Los hackerspaces comenzaron a finales de los 90' y se popularizaron en la segunda mitad de los 2000'. Ideológicamente hablando, la mayoría de los hacklabs se han politizado explícitamente como parte de una escena anarquista/autonomista más amplia, mientras que los hackerspaces, desarrollándose en la esfera de influencia libertaria alrededor del Chaos Computer CLub, no se definen necesariamente a sí mismos como abiertamente políticos. Mientras que las participantes en ambas escenas consideran sus actividades como orientadas hacia la liberación del conocimiento tecnológico y prácticas relacionadas, la interpretación de lo que "libertad" significa diverge. Un ejemplo concreto de como estas divergencias históricas e ideológicas se plasman, puede encontrarse en el estatus legal de los espacios: mientras que los hacklabs suelen ubicarse en edificios okupados, los hackerspaces son generalmente lugares de alquiler.

Despite the fact that these spaces share the same cultural heritage, some of their ideological and historical roots are indeed different. This results in a slightly different adoption of technologies and a subtle divergence in their organisational models. Historically speaking, hacklabs started in the middle of the 1990s and became widespread in the first half of the 2000s. Hackerspaces started in the late 1990s and became widespread in the second half of the 2000s. Ideologically speaking, most hacklabs have been explicitly politicised as part of the broader anarchist/autonomist scene, while hackerspaces, developing in the libertarian sphere of influence around the Chaos Computer Club, are not necessarily defining themselves as overtly political. While practitioners in both scenes would consider their own activities as oriented towards the liberation of technological knowledge and related practices, the interpretations of what is meant by “liberty” diverges. One concrete example of how these historical and ideological divergences show up is to be found in the legal status of the spaces: while hacklabs are often located in squatted buildings, hackerspaces are generally rented.

Este paper consta de tres secciones distintas. Las primeras dos secciones elaboran la genealogía histórica e ideológica de los hacklabs y los hackerspaces. La tercer sección unifica lo encontrado con la intención de contraponerlo a las diferencias existentes desde un punto de vista contemporáneo. Mientras que las secciones genealógicas son descriptivas, la evaluación en la última sección es normativa, preguntándose como las diferencias identificadas en el paper se juegan desde un punto de vista estratégico en la creación de espacios, sujetos y tecnologías postapocalípticos.

This paper is comprised of three distinct sections. The first two sections draw up the historical and ideological genealogy of hacklabs and hackerspaces. The third section brings together these findings in order to reflect on the differences from a contemporary point of view. While the genealogical sections are descriptive, the evaluation in the last section is normative, asking how the differences identified in the paper play out strategically from the point of view of creating postcapitalist spaces, subjects and technologies.

Nótese que en la actualidad los términos "hacklab" y "hackerspace" son usados en líneas generales como sinónimos. Al contrario de la categorización actual, uso hacklabs en su sentido antiguo (1990s) e histórico, con la intención de echar luz a las diferencias históricas e ideológicas que resultan en una aproximación de un modo diferente a la tecnología. Esto no es un puntillismo lingüístico, sino que un intento de permitir un entendimiento mas sutil de los ámbitos y prácticas en consideración. La continua evolución de estos términos, reflejando los cambios sociales que han tenido lugar, se encuentra registrada en Wikipedia. El artículo de Hacklab fue creado en 2006 (Wikipedia contributors, 2010a), el artículo de Hackerspace en 2008 (Wikipedia contributors, 2011). En 2010, el contenido del artículo Hacklab fue unido al artículo de Hackerspace. Esta unión fue justificada en la correspondiente página de discusión (Wikipedia contributors, 2010). Un usuario con el nombre de "Anarkitekt" escribió que "nunca he escuchado o leído nada que implicase que hay una diferencia ideológica entre los términos hackerspace y hacklab" (Wikipedia contributors, 2010b). Por tanto, el tratamiento del tema por parte de las wikipedistas apoya mi planteo de que la proliferación de los hackerspaces fue de la mano con un olvido de la historia que intento recapitular aquí.

Note that at the moment the terms “hacklab” and “hackerspace” are used largely synonymously. Contrary to prevailing categorisation, I use hacklabs in their older (1990s) historical sense, in order to highlight historical and ideological differences that result in a somewhat different approach to technology. This is not linguistic nitpicking but meant to allow a more nuanced understanding of the environments and practices under consideration. The evolving meaning of these terms, reflecting the social changes that have taken place, is recorded on Wikipedia. The Hacklab article was created in 2006 (Wikipedia contributors, 2010a), the Hackerspace article in 2008 (Wikipedia contributors, 2011). In 2010, the content of the Hacklab article was merged into the Hackerspaces article. This merger was based on the rationale given on the corresponding discussion page (Wikipedia contributors, 2010). A user by the name “Anarkitekt” wrote that “I’ve never heard or read anything implying that there is an ideological difference between the terms hackerspace and hacklab” (Wikipedia contributors, 2010b). Thus the treatment of the topic by Wikipedians supports my claim that the proliferation of hackerspaces went hand in hand with a forgetting of the history that I am setting out to recapitulate here.

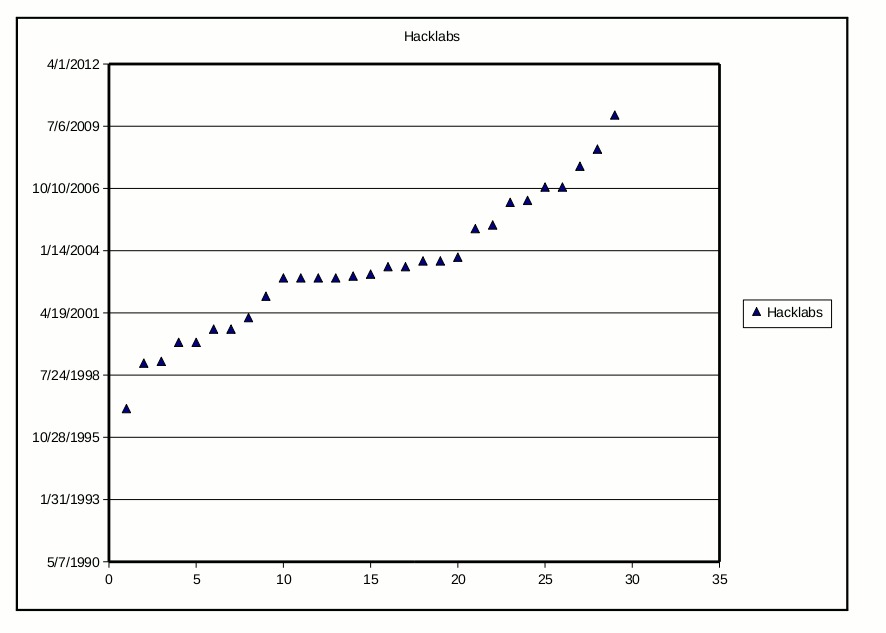

Figura 1. Encuesta de registro de dominios de la lista de hacklabs en hacklabs.org

Figure 1. Survey of domain registrations of the hacklabs list from hacklabs.org

- Los Hacklabs

- Hacklabs

El aumento de los hacklabs puede ser atribuído a un número de factores. Para esquematizar su genealogía, no centraremos aquí en dos contextos: el movimiento autonomista y el mediactivismo.Se da un resumido y simplificado recorrido de estas dos historias, que enfatisa elementos que son importantes desde el punto de vista de la emergencia de los hacklabs. La cultura hacker, de no menos importancia, será tratada en la siguiente sección con más detalle. Una definición de un artículo seminal, de Simon Yuill señala las formas de pensamiento básicas detras de estas iniciaticas (2008):

The surge of hacklabs can be attributed to a number of factors. In order to sketch out their genealogy, two contexts will be expanded on here: the autonomous movement and media activism. A shortened and simplified account of these two histories are given that emphasises elements that are important from the point of view of the emergence of hacklabs. The hacker culture, of no less importance, will be treated in the next section in more detail. A definition from a seminal article by Simon Yuill highlights the basic rationales behind these initiatives (2008):

"Los hacklabs son, mayoritariamente, espacios que funcionan a base de voluntarios proveyendo acceso público y gratuito a computadoras e internet. Usualmente hacen uso de maquinas rekuperadas y recicladas que corren GNU/Linux, y a la vez que proveen acceso a computadoras, la mayoría de los hacklabs tienen talleres funcionando en un rango de temas que va desde uso basico de la computadora e instalación de software GNU/Linux, hasta programación, electronica y radiodifución independiente (o pirata). Los primeros hacklabs se desarrollaron en Europa, usualmente surgiendo de tradiciones de centros sociales okupados y media labs comunales. En Italia se los conecta con los centros sociales autonomistas y en España, Alemania y en los Paises Bajos con movimientos de okupación anarquistas."

“Hacklabs are, mostly, voluntary-run spaces providing free public access to computers and internet. They generally make use of reclaimed and recycled machines running GNU/Linux, and alongside providing computer access, most hacklabs run workshops in a range of topics from basic computer use and installing GNU/Linux software, to programming, electronics, and independent (or pirate) radio broadcast. The first hacklabs developed in Europe, often coming out of the traditions of squatted social centres and community media labs. In Italy they have been connected with the autonomist social centres, and in Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands with anarchist squatting movements.”

Los movimientos autónomos surgieron del "shock cultural" (Wallerstein, 2004) de 1968, lo que incluyó una nueva ola de contestaciones contra el capitalismo, tanto en su forma de estado de bienestar como en su forma del Este como "capitalismo burocrático" (Debord [1970], 1977). Estaba vinculado concurrentemente con el levantamiento de las subculturas juveniles. Estaba orientado principalmente hacia la acción directa masiva y el establecimeinto de iniciativas que buscaban proveer una alternativa a las instituciones operadas por el Estado y el Capital. Su característica mas crucial era la auto-organización enfatizando la distribución formal del poder. En los 70', el movimiento autónomo jugó un rol en las políticas de Italia, Alemania y Francia (En orden de importancia) y en menor medida en otros paises europeoscomo Grecia (Wright, 2002). Las bases teóricas son que la clase trabajadora ( luego se generaliza a las oprimidas en general) pueden ser un actor histórico independiente ante el Estado y el Capital, construyendo sus propias estructuras de poder a travez de la autovalirisación y apropiación. Se nutrió del marxismo ortodoxo, el communismo de izquierda y el anarquismo, tanto en términos teóricos como en términos de una continuidad histórica y de contacto directo entre estos otros moviemientos. El auge y caída de las organizaciones terroristas de izquierda, que emergió de un contexto similar (como la RAF en Alemania o las Brigadas Rojas en Italia), ha marcado un quiebre en la historia de los movimientos autónomos. Después de esto, se volvieron menos coherentes y más heterogéneos. Dos prácticas específicas que instauraron las autonomistas son la okupación y el mediactivismo (Lotringer Marazzi, 2007).

The autonomous movement grew out of the “cultural shock” (Wallerstein, 2004) of 1968 which included a new wave of contestations against capitalism, both in its welfare state form and in its Eastern manifestation as “bureaucratic capitalism” (Debord [1970], 1977). It was concurrently linked to the rise of youth subcultures. It was mainly oriented towards mass direct action and the establishment of initiatives that sought to provide an alternative to the institutions operated by state and capital. Its crucial formal characteristic was self-organisation emphasising the horizontal distribution of power. In the 1970s, the autonomous movement played a role in the politics of Italy, Germany and France (in order of importance) and to a lesser extent in other European countries like Greece (Wright, 2002). The theoretical basis is that the working class (and later the oppressed in general) can be an independent historical actor in the face of state and capital, building its own power structures through self-valorisation and appropriation. It drew from orthodox Marxism, left-communism and anarchism, both in theoretical terms and in terms of a historical continuity and direct contact between these other movements. The rise and fall of left wing terrorist organisations, which emerged from a similar milieu (like the RAF in Germany or the Red Brigade in Italy), has marked a break in the history of the autonomous movements. Afterwards they became less coherent and more heterogenous. Two specific practices that were established by autonomists are squatting and media activism (Lotringer Marazzi, 2007).

La reapropiación de lugares físicos y de propiedades tiene una historia mucho más largan que el movimiento autónomo. Algunas veces, como es el caso de los asentamientos piratas descrito por Hakim Bey (1995,, 2003), estos lugares han evolucionado en ciudades para "formas de vida" alternativas (Agamben, 1998). La escasez de vivienda luego de la segunda guerra mundial resultó en una oleada de ocupaciones en el Reino Unido (Hinton, 1988) lo que necesariamente tomó un estatuto político y produjo experiencias en comunidad. Sin embargo, la especificidad de la okupación, se basa en la ocupación de casas como comienzo de una estrategia de reinvención de todas las esferas de la vida, mientras se confronta con las autoridades y el "status quo" más comunmente concebido. Mientras que muchas casas funcionaban como casas privadas, centrandoze en experimentar con estilos de vidas alternativos o simplemente para satisfacer necesidades básicas, otras optaron por jugar un rol en la vida urbana. Estas últimas son llamadas "centros culturales". Un centro cultural proveía espacio para inicitivas que buscaban establecer una alternativa a las instituciones oficiales. Por ejemplo, un "infoshop" sería la alternativa a un "mostrador de informes", librería y archivo, mientras que la "cocina de bicicletas" sería una alternativa a los locales de bicicletas y locales de reparación de bicicletas. Estos dos ejemplos muestran que entre las muchas instituciones a ser remplazadas, dos de las que son operadas por el Estado y el Capital estaban incluidas. Por otro lado, los espacios okupados tanto temporalmente como los mas o menos permanentes servían como bases, y algunas veces líneas de frente, de un conjunto de actividades de protesta.

The reappropriation of physical places and real estate has a much longer history than the autonomous movement. Sometimes, as in the case of the pirate settlements described by Hakim Bey (1995,, 2003), these places have evolved into sites for alternative “forms of life” (Agamben, 1998). The housing shortage after the Second World War resulted in a wave of occupations in the United Kingdom (Hinton, 1988) which necessarily took on a political character and produced community experiences. However, the specificity of squatting lay in the strategy of taking occupied houses as a point of departure for the reinvention of all spheres of life while confronting authorities and the “establishment” more generally conceived. While many houses served as private homes, concentrating on experimenting with alternative life styles or simply satisfying basic needs, others opted to play a public role in urban life. The latter are called “social centres”. A social centre would provide space for initiatives that sought to establish an alternative to official institutions. For example, the infoshop would be an alternative information desk, library and archive, while the bicycle kitchen would be an alternative to bike shops and bike repair shops. These two examples show that among the various institutions to be replaced, both those operated by state and capital were included. On the other hand, both temporary and more or less permanently occupied spaces served as bases, and sometimes as front lines, of an array of protest activities.

Con el inicio del neoliberalismo (Harvey, 2005; 2007), las okupas tuvieron que pelear duramente por su territorio, teniendo como resultado las "guerras okupas" de los años 90'. Lo que estaba en juego en estos choques que tenían frecuentemente calles enteras bajo bloqueo, era forzar al Estado y el Capital a reconocer a las okupaciones como una práctica social medianamente legítima. Mientras que el allanamiento y entrada a propiedad privada continuaba siendo ilegal, las okpuas recibian al menos una protección legal temporaria y las disputas debían ser resueltas en una corte, usualmente tomando un largo tiempo para concluirse. La okupación proliferó en ese "area gris" resultante. Prácticas de aplicación, leyes okupas y marcos de trabajo se establecieron el Reino Unido, Catalunia, Paises Bajos y Alemania. Algunos de los centros sociales mas poderosos ( como el EKH en Vienna) y un manojo de escenas fuertes en algunas ciudades (como Barcelona) lograron asegurar su existencia en la primer decada del 21º siglo. Los años recientes han visto una serie de represiones en las últimas zonas de okupaciones populares, como la abolición de las leyes de protección de okupas en los Paises Bajos (Usher,,2010) y discusiones sobre el mismo tema en el Reino Unido (House of Commons,, 2010).

With the onset of neoliberalism (Harvey, 2005; 2007), squatters had to fight hard for their territory, resulting in the “squat wars” of the 90s. The stake of these clashes that often saw whole streets under blockade was to force the state and capital to recognise squatting as a more or less legitimate social practice. While trespassing and breaking in to private property remained illegal, occupiers received at least temporary legal protection and disputes had to be resolved in court, often taking a long time to conclude. Squatting proliferated in the resulting ”grey area”. Enforcement practices, squatting laws and frameworks were established in the UK, Catalonia, Netherlands and Germany. Some of the more powerful occupied social centres (like the EKH in Vienna) and a handful of strong scenes in certain cities (like Barcelona) managed to secure their existence into the first decade of the 21^st^twenty first century. Recent years saw a series of crackdowns on the last remaining popular squatting locations such as the abolishment of laws protecting squatters in the Netherlands (Usher,, 2010) and discussion of the same in the UK (House of Commons,, 2010).

El mediactivismo se desarrolló por vías similares, sobre la base de una tradición de publicaciones independientes. Adrian Jones (2009) aduce una continuidad no sólo estructural sino también histórica en las prácticas de las radios piratas de los años sesentas y los conflictos de copyright contemporáneos protagonizados por la Pirate Bay. Desde un punto de vista estrictamente del activismo, una importante contribución temprana fue Radio Alice (est., 1976) que emergió desde la escena autonomista en Bologna (Berardi Mecchia, 2007). La radio pirata y su contraparte reformista, las estaciones de radio comunitarias, florecieron desde entonces. Sin embargo, rekuperar las frecuencias de radio era solamente un primer paso. Como explica Dee Dee Halleck, las media activistas pronto comenzaron a hacer uso de los productos electrónicos para el consumidor, como las cámaras filmadoras que se encontraron disponibles en el mercado desde finales de lso ochentas en adelante. Organizaron la producción en colectivos como "Paper Tiger Television" y la distribución en iniciativas desde las bases como "Deep Dish TV" que se focalizaba en tiempo de aire por satélite(Halleck, 1998). El siguiente paso lógico eran las tecnologías de la información y comunicación como las computadoras personales - que aparecían en el mercado en ese mismo tiempo. Era diferente a las cámaras filmadoras en el sentido de que era una herramienta de procesamiento de información para proósitos generales. Con la combinación del acceso a Internet comercial, cambió el panorama de la defensa política y las formas de organización. En la vanguardia de las teorías y prácticas en desarrollo alrededor de las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación estaba el "Critical Art Ensemble". Empezó con trabajos en video en 1986, pero continuó con otras tecnologías emergentes (Critical Art Ensemble, 2000). Aunque han publicado exclusivamente trabajos basados en Internet como Diseases of the Consciousness (1997), su aproximación táctica a los medios (tactical media) enfatiza el uso de la herramienta correcta para el trabajo correcto. En 2002 organizaron un taller el Eyebeam de Nueva York, que pertenece a la escena mas amplia de hackerspaces. Las nuevas media activistas jugaron un papel en la emergencia del movimiento de globalisazación alternativa (alterglobalisation), estableciendo la red Indymedia. Indymedia esta compuesta por centros locales de medios independientes y una infraestructura global manteniendolos juntos (Morris 2004 da una descripción justa). Focalizandose en publicaciones abiertas como principio editorial, la iniciativa rápidamente unió e involucrá tantas activistas que devino rapidamente una de las marcas mas reconocidas del movimiento de globalización alternativa, lentamente cayendo a la irrelevancia solamente a finales de la decada. Más o menos paralelo a este desarrollo, el movimiento "telestreet" era encabezado por Franco Berardi, también conocido como Bifo, quien estuvo involucrado en Radio Alice, mencionada con anterioridad. OrfeoTv comenzó en 2002 y usaba recibidores modificados de televisiones comerciales para transmisión televisiva pirata. (ver Telestreet, the Italian Media Jacking Movement, 2005). Aunque la iniciativa Telestreet pasó en una escala mucho menor que los desarrollos esbozados anteriormente, vale la pena señalarla porque las operadoras de Telestreet hicieron ingeniería inversa en productos masivos de la misma manera que lo hacen las hackers.

Media activism developed along similar lines, building on a long tradition of independent publishing. Adrian Jones (2009) argues for a structural but also historical continuity in the pirate radio practices of the 1960s and contemporary copyright conflicts epitomised by the Pirate Bay. On the strictly activist front, one important early contribution was Radio Alice (est., 1976) which emerged from the the autonomist scene of Bologna (Berardi Mecchia, 2007). Pirate radio and its reformist counterparts, community radio stations, flourished ever since. Reclaiming the radio frequency was only the first step, however. As Dee Dee Halleck explains, media activists soon made use of the consumer electronic products such as camcorders that became available on the market from the late 80s onwards. They organised production in collectives such as Paper Tiger Television and distribution in grassroots initiatives such as Deep Dish TV which focused on satellite air time (Halleck, 1998). The next logical step was information and communication technologies such as the personal computer — appearing on the market at the same time. It was different from the camcorder in the sense that it was a general purpose information processing tool. With the combination of commercially available Internet access, it changed the landscape of political advocacy and organising practices. At the forefront of developing theory and practice around the new communication technologies was the Critical Art Ensemble. It started with video works in 1986, but then moved on to the use of other emerging technologies (Critical Art Ensemble, 2000). Although they have published exclusively Internet-based works like Diseases of the Consciousness (1997), their tactical media approach emphasises the use of the right tool for the right job. In 2002 they organised a workshop in New York’s Eyebeam, which belongs to the wider hackerspace scene. New media activists played an integral part in the emergence of the alterglobalisation movement, establishing the Indymedia network. Indymedia is comprised of local Independent Media Centres and a global infrastructure holding it together (Morris 2004 gives a fair description). Focusing on open publishing as an editorial principle, the initiative quickly united and involved so many activists that it became one of the most recognised brands of the alterglobalisation movement, only slowly falling into irrelevance around the end of the decade. More or less in parallel with this development, the telestreet movement was spearheaded by Franco Berardi, also known as Bifo, who was also involved in Radio Alice, mentioned above. OrfeoTv was started in 2002 and used modified consumer-grade television receivers for pirate television broadcast (see Telestreet, the Italian Media Jacking Movement, 2005). Although the telestreet initiative happened on a much smaller scale than the other developments outlined above, it is noteworthy because telestreet operators reverse-engineered mass products in the same manner as hardware hackers do.

Siguiendo el ejemplo del Situacionismo con su idea principal de hacer intervenciones en los flujos de comunicación como punto de partida, las media activistas buscaron expandir lo que llamaban "interferencia cultural" en una práctica popular enfatizando elementos folclóricos(Critical Art Ensemble, 2001). Similarmente a las iniciativas educacionales proletarias de los movimientos de trabajadores clásicos (Por ejemplo Burgmann 2005:8 en Proletarian Schools), este acercamiento puso en primer plano los temas de acceso, regulación de frecuencia, educación popular, políticas editoriales y creatividad en masa, todos los cuales apuntaban en la dirección de bajar las barrerars de la participación de la producción cultural y tecnológica conjuntamente con establecer una infraestructura de comunicación distribuida para organizaciones anticapitalistas. Muchas media activisatas adirieron a alguna versión de la teoría de la hegemonía cultural de Gramsci, tomando la posición de que el trabajo cultural y educacional es tan importante como desafiar directamente las relaciones de propiedad. De hecho, este trabajo era visto como una continuación del vuelco de esas relaciones de propiedad en el área de los medios, cultura y tecnología. Esta tendencia a acentuar la importancia de la información para los mecanismos del cambio social fue fortalezida por las afirmaciones popularizadas por Michael Hardt y Antonio Negri de que el trabajo inmaterial y linguístico son el modo hegemónico de producción en la configuración contemporánea del capitalismo (2002, 2004). En el final extremo de este espectro, algunas argumentaban que elementos decisivos de la política dependen de performances de representación, usualmente mediatizadas, ubicando al media-activismo en el centro de la lucha contra el Estado y el Capital. Independientemente de estas creencias ideológicas, sin embargo, lo que distinguió a las practicantes de medios en terminos de identidad es que no se veían a si mismas simplemete como extranjeras o proveedoras de servicios, sino como una parte integral del movimiento social.Como deuestra Söderberg (2001), las convicciones políticas de una comunidad de usuarias puede ser una habilitadora usualmente desestima de creatividad tecnológica.

Taking a cue from Situationism with its principal idea of making interventions in the communication flow as its point of departure, the media activists sought to expand what they called “culture jamming” into a popular practice by emphasising a folkloristic element (Critical Art Ensemble, 2001). Similarly to the proletarian educational initiatives of the classical workers’ movements (for example Burgmann 2005:8 on Proletarian Schools), such an approach brought to the fore issues of access, frequency regulations, popular education, editorial policies and mass creativity, all of which pointed in the direction of lowering the barriers of participation for cultural and technological production in tandem with establishing a distributed communication infrastructure for anticapitalist organising. Many media activists adhered to some version of Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony, taking the stand that cultural and educational work is as important as directly challenging property relations. Indeed, this work was seen as in continuation with overturning those property relations in the area of media, culture and technology. This tendency to stress the importance of information for the mechanism of social change was further strengthened by claims popularised by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri that immaterial and linguistic labour are the hegemonic mode of production in the contemporary configuration of capitalism (2002, 2004). At the extreme end of this spectrum, some argued that decisive elements of politics depend on a performance of representation, often technologically mediated, placing media activism at the centre of the struggle against state and capitalism. Irrespectivly of these ideological beliefs, however, what distinguished the media practitioners in terms of identity is that they did not see themselves simply as outsiders or service providers, but as an integral part of a social movement. As Söderberg demonstrates (2011), political convictions of a user community can be an often overlooked enabler of technological creativity.

Estas dos tendencias entrelazadas se juntaron en la creación de los hacklabs. Las okupas, por un lado, incrustadas en los flujos urbanos de vida, tuvieron que usar infraestructuras de comunicación como el acceso a Internet y terminales de acceso público. Las media-activistas, por el otro lado, quienes estaban frecuentemente emplazadas en una comunidad local, necesitaban lugares para convocar, producir, enseñar y aprender.Como observa Marion Hamm cuando discute como los espacios físicos y virtuales se enredaron debido al uso de las activistas de los medios electrónicos de comunicación: " Esta práctica no es una realidad virtual como lo fue imaginada en los ochentas en tanto una simulación gráfica de la realidad. Ocurre en tanto en el teclado, como en los talleres técnicos, en las calles y en centros mediáticos temporales, en carpas, en centros socio-culturales y en casas okupadas."(Traducido por Aileen Derieg,, 2003). Un ejemplo de como convergen estas líneas es el Ultralab en Forte Prenestino, una fortaleza ocupada en Roma que es tambíen reconocida por sus políticas autónomas en Italia. Han declarado en su sitio web que el Ultralab es un "patrón emergente"(AvANa.net, 2005), uniendo varias necesidades tecnológicas de las comunidades apoyadas por el Forte. Las usuarias del centro social tienen una necesidad compartida de una red de area local de computadoras que conecte varios espacios en la okupación., de servidores para hostear páginas webs y listas de mails de los grupos locales, de instalar y mantener terminales de acceso público, de tener espacios de officina para los equipos gráficos y de prensa, y finalmente de tener un lugar de encuentro para compartir conocimiento. El punto de partida para este desarrollo fue el cuarto de servidores de AvANa, que empezó como un sistema de tablón de anuncios (BBS), que es, en 1994 un tablón de mensajes de acceso telefónico.(Bazichelli 2008:80-81). Como lo recuerda la video activista Agnese Trocchi,

These two intertwined tendencies came together in the creation of hacklabs. Squats, on the one hand, closely embedded in the urban flows of life, had to use communication infrastructures such as Internet access and public access to terminals. Media activists, on the other hand, who are more often than not also grounded in a a local community, needed venues to convene, produce, teach and learn. As Marion Hamm observes when discussing how physical and virtual spaces enmeshed due to the activists’ use of electronic media communication: “This practice is not a virtual reality as it was imagined in the eighties as a graphical simulation of reality. It takes place at the keyboard just as much as in the technicians’ workshops, on the streets and in the temporary media centres, in tents, in socio-cultural centres and squatted houses.” (Translated by Aileen Derieg,, 2003). One example of how these lines converge is the Ultralab in Forte Prenestino, an occupied fortress in Rome which is also renowned for its autonomous politics in Italy. The Ultralab is declared to be an “emergent pattern” on its website (AvANa.net, 2005), bringing together various technological needs of the communities supported by the Forte. The users of the social centre have a shared need for a local area computer network that connects the various spaces in the squat, for hosting server computers with the websites and mailing lists of the local groups, for installing and maintaining public access terminals, for having office space for the graphics and press teams, and finally for having a gathering space for the sharing of knowledge. The point of departure for this development was the server room of AvANa, which started as a bulletin board system (BBS), that is, a dial-in message board in 1994 (Bazichelli 2008:80-81). As video activist Agnese Trocchi remembers,

"La BBS AvANa estaba esparciendo el concepto de Telemática Subversiva: derecho al anonimáto, acceso para todas y democracias digital. La BBS AvANa estaba fisicamente localizada en Forte Prenestino el mas grande y viejo espacio okupado en Roma. Entonces al final de los 90' me encontré a mi misma trabajando con tecnología y el espacio imaginativo que la misma estaba abriendo en las jóvenes y enojadas mentes de las integrantes de las comunidades okupas, las activistas y delirantes." (citado en Willemsen, 2006)

“AvANa BBS was spreading the concept of Subversive Thelematic: right to anonymity, access for all and digital democracy. AvANa BBs was physically located in Forte Prenestino the older and bigger squatted space in Rome. So at the end of the 1990’s I found myself working with technology and the imaginative space that it was opening in the young and angry minds of communities of squatters, activist and ravers.” (quoted in Willemsen, 2006)

AvANa y Forte Prenestino se conectaron a la Contra Red Europea (ahora en ecn.org), la cual conectaba varios centros sociales okupados en Italia, proveyendo canales seguros de comunicación y presencia pública electrónica resiliente de los grupos antifacistas, el movimiento Disobbedienti, y otros grupos afiliados con las escenas okupa y autonónoma. Localizando los nodos dentro de las okupaciones tenía sus desventajas, pero también proveía un cierto nivel de seguridad física y política frente a las autoridades.

AvANa and Forte Prenestino connected to the European Counter Network (now at ecn.org), which linked several occupied social centres in Italy, providing secure communication channels and resilient electronic public presence to antifascist groups, the Disobbedienti movement, and other groups affiliated with the autonomous and squatting scenes. Locating the nodes inside squats had their own drawbacks, but also provided a certain level of physical and political protection from the authorities.

Otro ejemplo más reciente de corta duración, es la Hackney Crack House, un hacklab localizado en 95 Mare Street en London. Esta okupación situada en una casa de estilo Georgiana, y estaba compuesta por un edificio de teatro, un bar, dos niveles de espacios de vivienda y un sótano que tenía un taller de bicicletas y espacio para un estudio (see Foti, 2010). El hacklab preveía una red de area local y un servidor de medios para la casa, y servía como un espacio de toqueteo para las inclinadas hacia la tecnología.Durante eventos como el "Free School", las participantes, incluyendo tanto a novatas absolutas como a hobbistas mas dedicadas, podían aprender a usar tecnologías libres y de código abierto, seguridade de redes y testeo de penetración. En base diaria las actividades iban desde arreglar aparátos electronicos rotos pasando por la construcción de instalaciones de medios combinados a gran escala, hasta jugar a juegos de computadora.

Another, more recent example is the short lived Hackney Crack House, a hacklab located on 195 Mare Street in London. This squat situated in an early Georgian house was comprised of a theatre building, a bar, two stores of living spaces and a basement that housed a bicycle workshop and a studio space (see Foti, 2010). The hacklab provided a local area network and a media server for the house, and served as a tinkering space for the technologically inclined. During events like the Free School, participants, including both absolute beginners and more dedicated hobbyists, could learn to use free and open source technologies, network security and penetration testing. Everyday activities ranged from fixing broken electronics through building large-scale mixed media installations to playing computer games.

Las descripciones presentadas con anterioridad sirven para indicar como los hacklabs surgieron de las necesidades y aspiraciones de las okupas y media-activistas. Esta historía arrastra una serie de consecuencias. Primeramente, que los hacklabs entraban organicamente en el ethos anti-institucional cultivado por la gente en los espacios autónomos. En segundo lugar, estaban incrustados en el régimen político de los espacios, y eran sometidas a las mismas formas de frágil soveranía política que dichos proyectos desarrollaron. Tanto Forte Prenestino y Mare Street han escrito y des-escrito formas de comportarse que se esperaba que las usuarias siguieran. Esta última okupación había promocionado "Políticas de lugares mas seguros", declarando por ejemplo que la gente que exibía comportamientos sexistas, racistas o autoritarios debiera esperar ser confrontada, y si fuese necesario, excluida. En tercer lugar, la lógica politicada de las okupaciones, y mas especificamente la ideología detrás del anarchismo apropiativo, tuvo también sus consecuencias. Un centro social designado para ser una institución pública, cuya legitimidad yace en servir a su audiencia y barrio, si fuese posible de mejor manera de lo que lo hacen las autoridades locales, por lo cual el riesgo de desalojo es de alguna manera reducido. Por último,el estado de okupación fomenta un ambiente de complicidad. Consecuentemente, ciertas formas de ilegalidad son vistas como al menos necesarias, o algunas veces hasta deseable. Estos factores son cruciales para entender las diferencias entre hacklabs y hackerspaces, que será discutida en la sección 3.

The descriptions given above serve to indicate how hacklabs grew out of the needs and aspirations of squatters and media activists. This history comes with a number of consequences. Firstly, that the hacklabs fitted organically into the anti-institutional ethos cultivated by people in the autonomous spaces. Secondly, they were embedded in the political regime of these spaces, and were subject to the same forms of frail political sovereignty that such projects develop. Both Forte Prenestino and Mare Street had written and unwritten conducts of behaviour which users were expected to follow. The latter squat had an actively advertised Safer Places Policy, stating for instance that people who exhibit sexist, racist, or authoritive behaviour should expect to be challenged and, if necessary, excluded. Thirdly, the politicised logic of squatting, and more specifically the ideology behind appropriative anarchism, had its consequences too. A social centre is designated to be a public institution whose legitimacy rests on serving its audience and neighbourhood, if possibly better than the local authorities do, by which the risk of eviction is somewhat reduced . Lastly, the state of occupation fosters a milieu of complicity. Consequently, certain forms of illegality are seen as at least necessary, or sometimes even as desirable. These factors are crucial for understanding the differences between hacklabs and hackerspaces, to be discussed in Section 3.

Una rudimentaria encuesta basada en los registros a páginas (ver Figura 1. en el apéndice), investigación de escritorio y entrevistas muestra que los primeros hacklabs fueron establecidos en la decada alrededor del cambio de milenio (1995-2005). Su concentración en el Sur de Europa ha sido señalada por la organización de los "hackmeetins" anuales en Italia, que comenzaron en 1998. El Hackmeeting es un encuentro donde las practicantes pueden intercambiar conocimiento, conocer su trabajo, y disfrutar de la compañia de las otras. En Europa del Norte "plug n' politx", anfitrionada primero por "Egocity" (un cyber-cafe okupado en Zurich, Suiza) proveyó un punto de encuentro para proyectos afines en 2001. Bajo el mismo nombre se estableció una red, a la que le siguió un segundo encuentro en 2004 en Barcelona. Mientras tanto, Hacklabs.org (difunta desde 2006) fue montada en el 2002 para mantener una lista de hacklabas, vivos o muertos, y probeer noticias e infomación básica sobre el movimiento. Una revisión de las actividades publicitadas de los hacklabs, muestra talleres organizados alrededor de temas como el desarrollo de software libre, seguridad y anonimato, arte electrónico y producciones mediáticas.

A rudimentary survey based on website registrations (see Figure 1. in the appendix), desktop research and interviews shows that the first hacklabs were established in the decade around the turn of the millennium (1995-2005). Their concentration to South Europe has been underlined by the organisation of yearly Hackmeetings in Italy, starting in 1998. The Hackmeeting is a gathering where practitioners can exchange knowledge, present their work, and enjoy the company of each other. In North Europe plug’n’politix, hosted first by Egocity (a squatted Internet cafe in Zurich, Switzerland) provided a meeting point for like-minded projects in 2001. A network by the same name was established and a second meeting followed in 2004 in Barcelona. In the meantime, Hacklabs.org (defunct since, 2006) was set up in 2002 to maintain a list of hacklabs, dead or alive, and provide news and basic information about the movement. A review of the advertised activities of hacklabs show workshops organised around topics like free software development, security and anonymity, electronic art and media production.

Las actividades de Print, un hacklab localizado en una okupación en Dijon, que se llama "Les Tanneries", muestra el tipo de contribuciones que surgieron de estos lugares. La gente activa en Print han mantenido un laboratorio de computadoras con con acceso a internet gratuito para visitantes del centro social, y una colección de componentes de computadoras viejos que los invididuos pueden usar para construir sus propias computadoras. Han organizado eventos de distintos tamaños (de un par de personas hasta mil) relacionado con el software libre, como una fiesta para arreglar los últimos "bugs" restantes en el próximo lanzamiento del sistema operativo Debian GNU/Linux. Además, han proveído soporte de red y distribuido computadoras con acceso a Internet en el "European gathering of Peoples’ Global Action", un encuentro a nivel mundial de activistas de base conectados al movimiento de globalización alternativa. En una veta similar, han realizado varias protestas en la ciudad llamando la atención hacia temas relacionados con la vigilancia estatal y legislaciones de copyright.Estas acciones han construido una tradición de montar instalaciones arísticas en varios lugares dentro y alrededor del edificio, el ejemplo mas chocante es el grafitti enorme en el cortafuegos que dice “apt-get install anarchism”. Que es un broma técnica aludiendo a la manera en la que los programas son installados en el sistema Debian, tan técnica que de hecho funciona.

The activities of Print, a hacklab located in a squat in Dijon which is called Les Tanneries, show the kinds of contributions that came out of these places. People active in Print have maintained a computer lab with free Internet access for visitors to the social centre, and a collection of old hardware parts that individuals could use to build their own computers. They have organised events of various sizes (from a couple of people to a thousand) related to free software, like a party for fixing the last bugs in the upcoming release of the Debian GNU/Linux operating system. Furthermore, they have provided network support and distributed computers with Internet access at a European gathering of Peoples’ Global Action, a world-wide gathering of grassroots activists connected to the alterglobalisation movement. In a similar vein, they have staged various protests in the city calling attention to issues related to state surveillance and copyright legislations. These actions have built on a tradition of setting up artistic installations in various places in and around the building, the most striking example being the huge graffiti on the firewall spelling out “apt-get install anarchism”. It is a practical joke on how programs are set up on Debian systems, so practical that it actually works.

Otro ejemplo de el Sur de Europa es Riereta en Barcelona, un hacklab okupando un edificio separado que hace de anfitrión a un estudio de radio manejado por mujeres. Las actividades ahí, gravitan alrededor tres ejes, software libre, tecnología, y creatividad artística. Sin embargo, como un testimonio de la influencia del media-activismo, la mayoría de los proyectos y eventos están concentrados en producción de mediática, como el procesamiento en tiempo real de audio y video, transmitiendo y haciendo campaña contra el copyright y otras restricciones a la distribución libre de información. La lista de ejemplos podría facilmente hacerse mas larga, demostrando que la mayorñia de los hacklabs comparten ideas y prácticas similares y mantienen vínculos con las políticas de globalización alternativa, espacios okupados y (el nuevo) media-activismo.

Another example from South Europe is Riereta in Barcelona, a hacklab occupying a separate building that hosts a radio studio ran by women. The activities there gravitate around the three axes of free software, technology, and artistic creativity. However, as a testimony of the influence from media activism, most projects and events are concentrated on media production, such as real time audio and video processing, broadcasting and campaigning against copyright and other restrictions to free distribution of information. The list of examples could easily be made longer, demonstrating that most hacklabs share similar ideas and practicesand maintains links with alterglobalisation politics, occupied spaces and (new) media activism.

En resumen, debido a su situación histórica en los movimientos anticapitalistas y las barreras de acceso a la infraestructura de comunicación contemporanea, los hacklabs tienden a focalizarse en la adopción de redes de computadora y tecnologías mediáticas para usos políticos, esparciendo acceso a desposeídos y la defensa de la creatividad popular.

- Hackerspaces

Es probablemente una observación certera afirmar que los hackerspaces están en el tope de su popularidad en este momento. Como mencionamos en la introducción, muchas instituciones e iniciativas diferentes se llaman a sí mismas "hackerspaces". Por lo menos en Europa, Hay un núcleo de proyectos más o menos dirigidos por la comunidad que se definen a sí mismos como hackerspaces.El caso de los hacklabs ya fue descripto, pero es meramente un ejemplo del extremamente amplio espectro político. Existen una serie de variaciones poblando el mundo, como son los fablabs, makerlabs, telecottages, medialabs, laboratorios de innovación y espacios de co-working. Lo que distingue a los ultimos dos del resto ( y posiblemente también de los fablabs) es que están armados en un contexto institucional, ya sea una universidad, una compañia o una fundación. Y la mayoría de las veces su misión es la de adoptar innovaciones. Tales espacios tienden a focalizarse en resultados concretos como proyectos de investigación o productos comerciales. "Telecottages" y "telehouses" están a la mitad del espectro. Están típicamente financiadas por fondos de desarrollo para mejorar a través de las TICs las condiciones sociales y económicas locales. Inclusive los makerlabas son algunas veces gestaciones comerciales ( como Fablab en Budapest, que no debe confundirse con el Centro Autónomo Hungariano para el Conocimiento mencionado anteriormente), basado en la idea de proveer como servicio acceso a herramientas para para compañias e individuos. Los Fablabs pueden ser la nueva generación en la evolución de los hackerspaces, faocalizandose en la manufactura de proyectos de construcción personalizada. Esta encuadrado como una fábrica repensada a partir de la inspiración del modelo de producción de pares (MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, 2007). Lo que caracteriza a los hackerspaces - junto con la mayoría de los fablabs - es que están armados por hackers y para hackers con la misión principal de apoyar el hackeo.

It is probably safe to state that hackerspaces are at the height of their popularity at the moment. As mentioned in the introduction, many different institutions and initiatives are now calling themselves “hackerspaces”. At least in Europe, there is a core of more or less community-led projects that define themselves as hackerspaces. The case of hacklabs have already been described, but it is merely one example from the extreme end of the political spectrum. There are a number of more variations populating the world, such as fablabs, makerlabs, telecottages, medialabs, innovation labs and co-working spaces. What distinguishes the last two from the others (and possibly also from fablabs) is that they are set up in the context of an institution, be that a university, a company or a foundation. More often than not , their mission is to foster innovation. Such spaces tend to focus on concrete results like research projects or commercial products. Telecottages and telehouses occupy the middle of the range- They are typically seeded from development funds to improve local social and economic conditions through ICTs. Even makerlabs are sometimes commercial ventures (like Fablab in Budapest, not to be confused with the Hungarian Autonomous Centre for Knowledge mentioned above), based on the idea of providing access to tools for companies and individuals as a service. Fablabs may be the next generation of the hackerspace evolution, focusing on manufacturing of custom built objects. It is framed as a re-imagining of the factory with inspiration from the peer production model (MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms, 2007). What sets hackerspaces apart — along with most fablabs — is that they are set up by hackers for hackers with the principal mission of supporting hacking.

Este es por lo tanto, el momento apropiado del paper para centrarnos en el aspecto social e histórico del fenómeno del hacking. Esto no quiere decir que los hacklabs - como lo indica su nombre - estarían menos involucrados en una tradición inspirada por hackers. Podría hacerse un estudio separado dedicado al entrelazamiento de esos dos movimientos en el movimiento del sofware libre. Sin embargo, ya que lso dos movimienos contribuyen en igual medida pero de distintas maneras, este aspecto no será elaborado aquí en extensión ya que dicho contraste sería difícil de reflejar. Por lo tanto se asume que muhco de lo que dice aquí sobre cultura hacker y su influencia en el movimiento de hackerspaces aplica igualmente a los hacklabs.

This is therefore the right point in the paper to dwelve on the social and historical phenomena of hacking. This is not to say that hacklabs — as is indicated by their name — would be less involved in and inspired by the hacker tradition. A separate study could be devoted to these two movements’ embeddedness in the free software movement. However, since both movements are contributing to an equal extent but in different ways, this aspect will not be elaborated here at length as the contrast would be more difficult to tease out. It is hence assumed that much of what is said here about hacker culture and its influence on the hackerspace movement applies equally to hacklabs.

Los comienzos de la cultura hacker están bien documentados. También comienza, interesantemente, en los años 60' y se esparce en los 70', similarmente a la historia del movimiento autnomo. De hecho, en algún sentido puede ser considerada como una de las culturas juveniles que Wallerstein atribuye al "shock cultural" de 1968 (2004). Para no perderse en la mitología, mantendremos la historia corta y esquemática. Un semillero pareciese haber sido la cultura universitaria personificada por el Laboratorio de Inteligencia Articial del MIT y cultivada en media dozena de otros institutos de investigación alrededor de los EEUU. Otra fue la escena "phreaker" la cual se encuentra expresada en la revista de corte Yippie "TAP". Mientras que los anteriores se encontraban trabajando en descubrimientos de ingeniería como las primeras computadoras y sistemas operativos, o como redes precursoras a la Internet, estos últimos hacían lo opuesto: hacían ingeniería inversa para obtener información y tecnologías de comunicación, que en la época principalmente eran redes telefónicas. En 1984 ATT se separa en compañias mas chicas - la "Baby Bells", pero no antes de que partes importantes de la red fuesen apagadas por phreakers (Slatalla Quittner 1995, Sterling, 1992). El mismo año supo ver, el último número de TAP y el primer número de la revista 2600, aún activa. La cultura universitaria fue preservada en el Jargon File en 1975 el cual todavía es mantenido (Steele Raymond, 1996). Fue el inventor del Cyberpunk, William Gibson, el que popularizó el término cyberespacio en su novela Neuromancer. Inspiró por lo tanto, la cultura cyberpunk que dió un completo - sino "real" - Weltanschauung (Visión del mundo) a la cultura hacker. La idea de un futuro oscuro, donde la libertad sólo puede encontrarse en los bordes y las corporaciones gobiernan el mundo, llamaba tanto a los hackers de universidad como a los prheakers. Las estrellas del underground "prheaker" habían sido perseguidas por las autoridades legales por sus "pranks" a los gigantes de la comunicación, mientras que Richard Stallman - " la última de [la primer generación] las verdaderas hackers" (Levy [1984], 2001) - inventó el software libre en 1983 y establece la lucha contra la privatización creciente del conocimiento por parte de las corporaciones, que podía verse en aquel entonces en la expansión de las demandas de copyright de software, el esparcimiento de arreglos de confidencialidad, y la "proliferación" de compañias "start-up".

The beginnings of the hacker subculture are well-documented. Interestingly, it also starts in the 1960s and spreads out in the 1970s, much like the history of the autonomous movement. Indeed, in a sense it can be considered as one of the youth subcultures which Wallerstein attributes to the “cultural shock” of 1968 (2004). In order not to be lost in the mythology, the story will be kept brief and schematic. One hotbed seems to have been the university culture epitomised by the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and cultivated in half a dozen other research institutes around the USA. Another one was the phreaker scene that found its expression in the Yippie spinoff magazine TAP. While the former were working on engineering breakthroughs such as early computers and operating systems, as well as on networks precursoring the Internet, the latter were doing the opposite: reverse-engineering information and communication technologies, which mainly meant telephone networks at the time. In 1984 ATT was broken into smaller companies — the Baby Bells, but not before important parts of the network had been shut down by phreakers (Slatalla Quittner 1995, Sterling, 1992). The same year saw the last issue of TAP and the first issue of the still active 2600 magazine. The university culture was preserved in the Jargon File in 1975 which is still maintained (Steele Raymond, 1996). It was the inventor of cyberpunk, William Gibson, popularised the term cyberspace in his novel Neuromancer. He thus inspired the cyberpunk subculture which gave a complete — if not “real” — Weltanschauung to hacker culture. The idea of a dark future where freedom is found on the fringes and corporations rule the world spoke to both the university hackers and the phreakers. The stars of the phreaking underground had been persecuted by law authorities for their pranks on the communication giants, while Richard Stallman — “the last of the [first generation of] true hackers” (Levy [1984], 2001) — invented free software in 1983 and set out to fight the increasing privatisation of knowledge by corporations, as could then be seen in the expansion of copyright claims to software, the spread of non-disclosure agreements, and the mushrooming of start-up companies.

La historia del movimiento hacker en Europa, no ha sido tan bien documentada. Una instancia importante es el Chaos Computer Club que fue fundado en 1981 por Wau Holland y otras integrantes del grupo editorial del diario de una Zona Temporalmente Autónoma en un edificio de Kommune I., una famosa okupación autónoma (Anon, 2008:85). El Chaos Computer Club pasó a la luz en 1984. Las hackers pertenecientes al club se habían transferido 134,000 Marcos Alemane a través del sistema nacional de videotex, llamado Bildschirmtext o BTX. La Oficina Postal tenía un monopólio de hecho en el mecado con este producto obsoleto, y aseguraba mantener una red segura inclusive despues de haber sido notificados sobre el exploit. El dinero fue devuelto al otro día en frente de la prensa. Esto comenzó la relación tumultuosa del Club con el govierno alemán, que dura hasta estos días.

The history of the hacker movement in Europe has been less well documented. An important instance is the Chaos Computer Club which was founded in 1981 by Wau Holland and others sitting in the editorial room of the taz paper in the building of Kommune I., a famous autonomous squat (Anon, 2008:85). The Chaos Computer Club entered into the limelight in 1984. Hackers belonging to the club had wired themselves 134,000 Deutsche Marks through the national videotex system, called Bildschirmtext or BTX. The Post Office had practical monopoly on the market with this obsolete product, and claimed to maintain a secure network even after it had been notified about the exploit. The money was returned the next day in front of the press. This began the Club’s tumultuous relationship with the German government that lasts until today.

En su estudio de la cultura hacker, Gabriella COleman y Alex Golub plantean que en el tiempo que se ha mantenido unida, esta subcultura manifiesta una inovativa pero históricamente determinada versión del liberalismo, mientras que en sus múltiples tendencias expresa y explota algunas de las contradicciones inherentes a la misma tradición política (2008). Se concentran en tres corrientes de prácticas hackers: cryptolibertad, software libre y de código abierto, y el underground hacker. Sin embargo, no pretenden que dichas categorías exausten la riqueza de la cultura hacker. Al contrario, en un artículo de comentario en el "Atlantic", Coleman (2010) explícitamente menciona que la escena de seguridad informática ha sido sub-representada en la literatura sobre hackers. Las tres tendencias identificadas en su texto difieren ligeramente de la clasificación que sugiero aquí. La invención técnica y legal del proyecto de Stallman, plantó al software libre como uno de los pilares del hacking para las próximas décadas. Los exploits de las phreakers abrieron un camino para el underground hacker donde su carácter lúdico inicial se desarrolló en dos direcciones, hacia las ganancias o hacia lo político.

In their study of the hacker culture, Gabriella Coleman and Alex Golub have argued that as far as it hangs together, this subculture manifests an innovative yet historically determined version of liberalism, while in its manifold trends it expresses and exploits some of the contradictions inherent to the same political tradition (2008). They concentrate on three currents of hacker practice: cryptofreedom, free and open source software, and the hacker underground. However, they do not claim that these categories would exhaust the richness of hacker culture. On the contrary, in a review article in the Atlantic, Coleman (2010) explicitly mentions that the information security scene has been underrepresented in the literature about hackers. The three tendencies identified in their text differ slightly from the classification I am suggesting here. Stallman’s legal invention and technical project cemented free software as one pillar of hackerdom for the coming decades. The exploits of the phreakers opened a way for the hacker underground where its initial playfulness developed in two directions, towards profit or politics.

En Europa, la postura del Chaos Computer Club, allanó en camino para la investigación independiente de seguridad informáitca. Admitidamente, todas aquellas aproximaciones se concentraron en una interpretación específica de la libertad individual, la cual entiende a la libertad como una cuestión de conocimiento. Mas aún, a este conocimiento se lo concidera producido y circulado en una red de humanas y computadoras - en contraste directo con la versión del liberalismo asociado con el individualismo romántico, como lo observan Coleman y Golub. Por lo tanto, este es un liberalismo antihumanista tecnologicamente informado. Las hackers toman distintas posturas dentro de estos parámetros que algunas veces se complementan y algunas veces se contradicen. La comunidad del software libre ve al acceso universal del conocimiento como la condición escencial de la libertad. El underground hacker ejerce el conocimiento para garantizar la libertad de un individuo o una facción. Las expertas en seguridad informática de "sombrero gris" ven a la divulgación completa como la mejor manera de asegurar la estabilidad de una infraestructura, y por lo tanto la libertad de comunicación. La divulgacióm completa refiera a la práctica de liberar información y herramientas que puedan revelar fallas de seguridad al público. Esta idea surge de la tradicion de las cerrajeras del siglo del siglo XIX, quienes proponían que las mejores cerraduras están construidas sobre principios ampliamente comprendidos, y no sobre secretos: el único secreto, a ser gurdado en privado, debiera ser la llave misma.(Hobbs, Tomlinson Fenby [1853] 1868:2 citado en Blaze 2003 como en Cheswick, Bellovin Rubin 2003:120). La idea de que la libertad depende del conocimiento, y que a la vez, el conocimiento depende de la libertad, está articulada en el aforismo hacker atribuido a Stewart Brand: "La información quiere ser libre."(Clarke, 2001).

In Europe, the stance of the Chaos Computer Club paved the way for independent information security research. Admittedly, all of those approaches concentrated on a specific interpretation of individual freedom, one which understands freedom as a question of knowledge. Moreover, this knowledge is understood to be produced and circulated in a network of humans and computers — in direct contrast to the version of liberalism associated with romantic individualism, as Coleman and Golub observes. Therefore, this is a technologically informed antihumanist liberalism. Hackers carve out different positions within these parameters that sometimes complement and sometimes contradict each other. The free software community sees the universal access to knowledge as the essential condition of freedom. The hacker underground wields knowledge to ensure the freedom of an individual or a faction. “Gray hat” information security experts see full disclosure as the best way to ensure the stability of the infrastructure, and thus the freedom of communication. Full disclosure refers to the practice of releasing information and tools revealing security flaws to the public. This idea goes back to the tradition of 19th century locksmiths, who maintained that the best locks are built on widely understood principles instead of secrets: the only secret, to be kept private, should be the key itself (Hobbs, Tomlinson Fenby [1853] 1868:2 cited in Blaze 2003 as well as Cheswick, Bellovin Rubin 2003:120). The idea that freedom depends on knowledge and, in turn, knowledge depends on freedom, is articulated in the hackers aphorism attributed to Stewart Brand: “Information wants to be free.” (Clarke, 2001).

Durante el curso de la decada de los 90' el mundo hacker vio el armando de instituciones que han seguido de pie hasta el día de hoy. A partir de las tres sub-tradiciones que mencionamos antes han crecido distintas industrias, dandole de comer a profesionales en pleno empleo, trabajadoras precarias, y a entusiastas. La "Electronic Frontier Foundation" fue establecida en 1990 en los EE. UU. para defender y promover los valores hackers a través de apoyo legal, trabajo político y proyectos específicos en educación e investigación. Ocupa una posición muy distinta, pero comparabl econ el "Chaos Computer Club" en Europa. Los primeros discursos de la EEF como el de john Perry Barlow Una declaración de la independencia del cyberespacio invoca la narrativa de películas del lejano Oeste sobre un territorio indigena propenso a ser ocupado por el Este civilizatorio. Esta llena de referencias a los Padres Fundadores y a la constitución Estadounidense(1996).Conferencias, reuniones y campamentos refiriendose a las tres tendencias anteriores se convirtieron en extremadamente populares, similarmente a como la industria del cine progresivamente se apollaba en festivales. El "Chaos Communication Congress" desde 1984 y es hoy en día el evento más prominente en Europa, mientras que en EE. UU. H.O.P.E. fue organizado en 1994 por la gente que rodea la revista 2600, y todavía se mantiene fuerte. Los campamentos hackers fueron iniciados por una serie de eventos en los paises bajos que funcionan desde 1989. Estas experiencias solidificaron y popularizaron al movimiento hacker y el deseo por espacicos hackers permanentes era parte de este desarrollo.

During the course of the 1990s the hacker world saw the setting up of institutions that have been in place up until now. From all three sub-traditions mentioned above have grown distinct industries, catering to fully employed professionals, precarious workers, and enthusiasts alike. The Electronic Frontier Foundation was established in 1990 in the United States to defend and promote hacker values through legal support, policy work and specific educational and research projects. It occupies a position very different but comparable to the Chaos Computer Club in Europe. Early EFF discourse like John Perry Barlow’s A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace invokes the Western movie narrative of an indigenous territory prone to be occupied by the civilising East. It is littered withreferences to the Founding Fathers and the U.S. Constitution (1996). Conferences, gatherings and camps addressing the three tendencies above became extremely popular, similarly to how the film industry increasingly relied on festivals. The Chaos Communication Congress has run from 1984 and is now the most prominent event in Europe, while in the USA H.O.P.E. was organised in 1994 by the people around the 2600 magazine, and is still going strong. Hacker camping was initiated by a series of events in Netherlands running since 1989. These experiences solidified and popularised the hacker movement and the desire for permanent hacker spaces was part of this development.

Como señaló Nick Farr (2009), la primer ola pionera de hackerspaces fue fundada en los 90', de igual modo que los hacklabs. L0pht se asentó en 1992 en el área de Boston como un club a base de membresías que ofrecía un espacio físico compartido y una estructura virtual para un grupo selecto de gente. Algunos otros lugares fueron comenzados en esos años en los EE.UU. basados en este modelo "encubierto". En Europa, C-base en Berlín comenzó con un perfil más público en 1995, promoviendo el acceso libre a Internet y sirviendo como un lugar común para varios grupos comunitarios. Estos espacios de segunda ola "probaron que las hackers podían ser abiertas sobre su trabajo, organizarse oficialmente, ganar reconocimiento por parte del gobierno y respeto por parte del público viviendo y aplicando la Ética hacker en sus esfuerzos" (Farr,2009). Sin embagro, es con la actual tercer hora, que el número de hackerspaces comenzó a crecer expoencialmente y que se desearrolló como un tipo de movimiento global. Considero que el término hackerspaces no era comunmente usado antes de este punto y que el pequeño número de hackerspaces que existían eran menos consistentes y todavía no habían desarrollado las características de un movimiento. Notablemente, este es el contraste con la narrativa de los hacklabs presentada con anterioridad que aparecen como un movimiento político más consistente.

As Nick Farr (2009) has pointed out, the first wave of pioneering hackerspaces were founded in the 1990s, just as were hacklabs. L0pht stated in 1992 in the Boston area as a membership based club that offered shared physical and virtual infrastructure to select people. Some other places were started in those years in the USA based on this “covert” model. In Europe, C-base in Berlin started with a more public profile in 1995, promoting free access to the Internet and serving as a venue for various community groups. These second wave spaces “proved that hackers could be perfectly open about their work, organise officially, gain recognition from the government and respect from the public by living and applying the Hacker ethic in their efforts” (Farr, 2009). However, it is with the current, third wave that the number of hackerspaces begun to grow exponentially and it developed into a global movement of sorts. I argue that the term hackerspaces was not widely used before this point and the small number of hackerspaces that existed were less consistent and did not yet develop the characteristics of a movement. Notably, this is in constrast with narrative of the hacklabs presented earlier which appeared as a more consistent political movement.

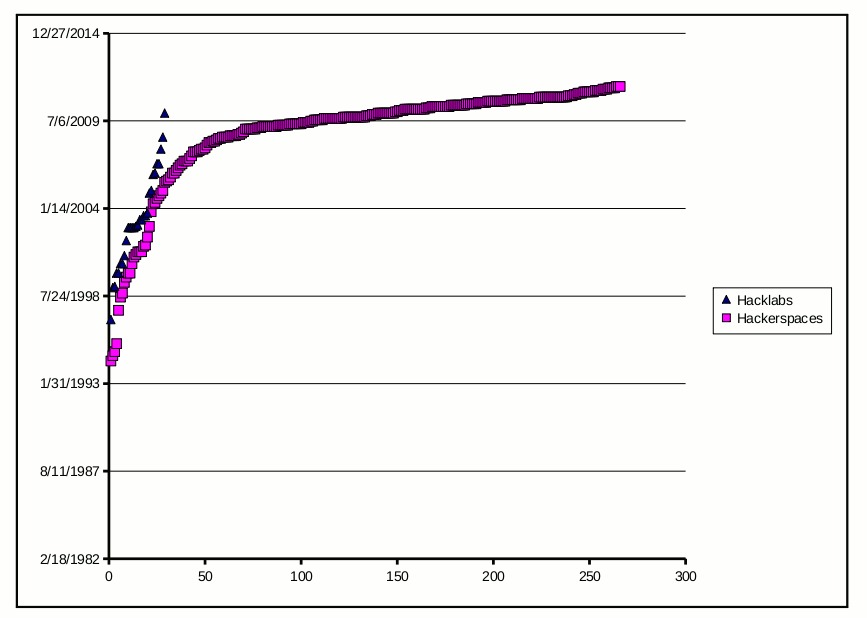

Varias cuentas (por ejemplo Anon, 2008) señalan una serie de charlas en 2007 y 2008 que insciraron, y continúan inspirando, la fundación de nuevos hackerspaces, sin embargo, la proliferación parece haber comenzado antes. En 2007 Farr organizó un proyecto llamado "Hackers on a Plane", que trajo hackers de los EE. UU. al "Chaos Communication Congress", e incluía un tour de los hackerspaces del área. Ohlig y Weiler del hackerspace C4 en Cologne dieron una charla innovadora en la conferencia, llamada Construyendo un Hackerspace (2007). La conferencia definía los patrones de diseño de un hackerspace, los cuales están escritos en forma de un catesismo y proveen soluciones a los problmeas mas comunes que surgen durante la organización de un hacrespace. Más importante aún, ha canonizado el concepto de hackerspace e impuesto la idea de armar nuevos alrededor de del mundo en la agenda del movimiento hacker. Cuando la delegación estadounidense volvió a casa, presentaron sus experiencias bajo el título programático Construyendo Hackerspaces en todos lados: Tus Escusas son Inválidas. Aseguraban que "cuatro personas pueden empezar un hackerspace sustentable", y mostraban como hacerlo (Farr et al,2008). En el mismo año se concretó el lanzamiento de hackerspaces.org, en Europa con Construyendo un movimiento internacional: hackerspaces.org (Pettis et al, 2008), y también en Agosto en el H.O.P.E. norteamericano (Anon, 2008). Mientras que el dominio esta registrado desde el 2006, el Internet Archive vio la primera página de internet ahí en el 2008 teniendo en lista 72 hackespaces. Desde entonces las plataformas de comunicación que provee el portal se volvieron un elemento vital en el movimiento de hackerspaces, llevando el slogan "Construye! Une! Multiplica!" (hackerspaces.org, 2011).Una encuesta sobre la fecha de inicio de los 500 hackerspaces registrados muestra una creciente desde 2008 (ver Figura 2).

Several accounts (for example Anon, 2008) highlight a series of talks in 2007 and 2008 that inspired, and continue to inspire, the foundation of new hackerspaces. Judging from registered hackerspaces, however, the proliferation seems to have started earlier. In 2007 Farr organised a project called Hackers on a Plane, which brought hackers from the USA to the Chaos Communication Congress, and included a tour of hackerspaces in the area. Ohlig and Weiler from the C4 hackerspace in Cologne gave a ground-braking talk on the conference entitled Building a Hackerspace (2007). The presentation defined the hackerspace design patterns, which are written in the form of a catechism and provide solutions to common problems that arise during the organisation of the hackerspace. More importantly, it has canonised the concept of hackerspaces and put the idea of setting up new ones all over the world on the agenda of the hacker movement. When the USA delegation returned home, they presented their experiences under the programmatic title Building Hacker Spaces Everywhere: Your Excuses are Invalid. They argued that “four people can start a sustainable hacker space”, and showed how to do it (Farr et al, 2008). The same year saw the launch of hackerspaces.org, in Europe with Building an international movement: hackerspaces.org (Pettis et al, 2008), and also in August at the North American HOPE (Anon, 2008). While the domain is registered since 2006, the Internet Archive saw the first website there in 2008 listing 72 hackerspaces. Since then the communication platforms provided by the portal became a vital element in the hackerspaces movement, sporting the slogan “build! unite! multiply!” (hackerspaces.org, 2011). A survey of the founding date of the 500 registered hackerspaces show a growing trend from 2008 (see Figure 2).

Notablemente, la mayoría de estos desarrollos se focalizaron en las características formales de los hackerspaces, por ejemplo como manejar problemas y hacer crecer una comunidad. Enfatizaban un modelo de membresía abierta para mantener un espacio común de trabajao que funcione como un ambiente de producción cooperativo, socializante y de aprendizaje. Sin embargo, el contenido de las actividades que transcurren en los hackerspaces tambíen muestra una gran consistencia. Las tecnologías usadas pueden ser descriptas como capas de sedimentación: las nuevas tecnologias ocupan su lugar al lado de las viejas, sin convertirse en absolutamente obsoletas. En primera isntancia, el hecho de que las hackers colaboren en un espacio físico significó un resurgimiento del trabajo en electrónica, que se unía con la tendencia establesida de toquetear computadoras físicas. Un esbozo de las áreas de investigación conectadas puede ser (en orden de aparición): desarrollo de software libre, reciclaje de computadoras, redes mesh inalámbricas, microelectrónica, hardware abierto, impresión 3d, talleres de maquinaría y cocina.