In this article, we'll briefly discuss the chemistry behind plant nutrition. We'll then use my calculator to design a complete two-part hydroponic fertilizer customized for my hard tap water, blending from individual salts. We'll send a sample of that for laboratory analysis, and review those results.

Plants need 16 elements1 to grow. Of those, carbon, hydrogen and oxygen are available from water and air. This leaves 13 essential elements that must be supplied by fertilizer or soil:

N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn, B, Mo, Cl

The most important are nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. By convention, fertilizers are labeled with three numbers representing that percent N-P-K2. Soil or soil-like potting mix will often provide enough of the remaining elements that no further attention is required, allowing many growers to ignore everything except that N-P-K.

But in hydroponics, there's no soil. This is true both in pure hydroponic methods like DWC, where the roots are directly in water, and in inert media like rockwool that provide mechanical support but no fertility. So hydroponic fertilizers must be complete, including all essential elements. The plants take the elements up as ions. For the metals that's usually just the corresponding cation (e.g., K as K+, Ca as Ca++), but for the other elements it may be a more complex ion (e.g. N as NH4+ or NO3-, P as PO4---). A cation and an anion together form a salt, and fertilizers are blended from salts to achieve the desired element ratio. For example, potassium nitrate contributes both potassium and nitrogen.

Complete fertilizers are readily available pre-blended. Liquid concentrates are sold for amateur growers, for example the General Hydroponics Flora series. These are easy to use, since they can be measured by volume and don't need shaking to dissolve; but they're also rather bulky and expensive per unit of fertility, since they're mostly water. Commercial growers typically buy powdered solid nutrients, measure them by weight, and dissolve them into liquid concentrates themselves.

For example, Masterblend 4-18-383 tomato fertilizer is readily available, and despite the name is at least roughly suitable for growing almost any plant species. It contains almost all the essential elements, but no calcium. This is because in a concentrated solution, the calcium will precipitate against phosphates or sulfates, dropping out as a sediment at the bottom of the tank that's unavailable to the plants. Complete fertilizers should always come in at least two parts4, one with the calcium and one with the sulfates and phosphates.

That Masterblend product also contains very little magnesium5, and thus requires additional magnesium sulfate. Kits are readily available with that Masterblend (or another similar almost-complete fertilizer), calcium nitrate, and magnesium sulfate in the correct ratio. I've been growing for about a year with:

0.4 g/L Masterblend

0.4 g/L Ca(NO3)2

0.2 g/L MgSO4

For some mature plants, I use a stronger solution in the same ratio. This Masterblend is a very common choice among amateur growers. It's working relatively well for me, but not ideally:

-

My water has quite high alkalinity6, with initial pH around 8.5. Ideal pH for most plants is around 6.0. So I use a large amount of phosphoric acid7 to bring my pH down, which adds adds more phosphorus than the plants need to my nutrient profile. I'd like to decrease the phosphorus in the fertilizer to offset, but I can't remove the phosphorus already blended into the Masterblend.

-

Beyond the effect on the plants, the extra phosphate also precipitates against calcium in the nutrient solution. That calcium phosphate precipitate tends to clog drippers, and generally make a mess. So for that reason too, I'd like to decrease the phosphate, and slightly decrease the calcium.

-

As my reservoir empties, I top it up with new solution. This means that any ions not taken up by the plants will concentrate, and eventually become toxic. Sodium and chloride are the usual offenders here, though others are possible too. Masterblend 4-18-38 gets some of its potassium from potassium chloride, perhaps because tomatoes are relatively salt-tolerant and KCl is cheaper than other sources of potassium. To get rid of that accumulated chloride, I need to periodically dump my reservoir and restart fresh. That works, but it's a nuisance and a waste of water.

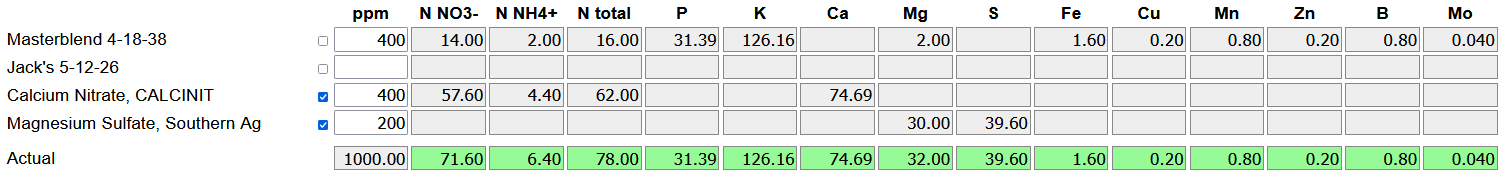

So I wanted to switch to a custom nutrient profile without these problems. To start, I used the calculator to look at my existing profile. Note that 0.4 g/L = 400 mg/L, which is 400 ppm since the density of water is around 1 kg/L.

The calculator gives me a breakdown by element of the overall nutrient profile. As a special case, total nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen, and nitrate nitrogen are tracked separately. In soil, nitrifying bacteria will convert ammonium to nitrate, so the form in which nitrogen is applied doesn't matter much. In hydroponics these bacteria aren't necessarily present; so plants see the fertilizer's nitrate:ammonium ratio directly, and too much ammonium can be toxic to the plants. That ratio also affects pH trend, since uptake by the plant effectively swaps an NH4+ ion for an H+ (decreasing pH), but swaps an NO3- for an HCO3- (increasing pH). Typical hydroponic fertilizers provide about 90% of the nitrogen as nitrate, the rest as ammonium.

Chlorine is an essential element, but it's required in such small amounts and present naturally in such large amounts that deficiency is practically impossible. There's therefore no need to deliberately add any, so it's not considered in that breakdown.

Starting from my existing profile, the changes I wanted to make were to:

-

Remove all chloride.

-

Reduce the calcium by about 35 ppm, since my water utility's website indicates that my tap water should provide at least that much.

-

Reduce the magnesium by about 12 ppm, since my tap water also provides that.

-

Reduce the phosphorus to zero, since the acid used to adjust pH provides more than enough.

-

Reduce the copper, zinc, and manganese, for fear they'd concentrate and become toxic in the same way as sodium or chloride8.

To make these changes, I edited the element concentrations in the "goal" line of the calculator accordingly.

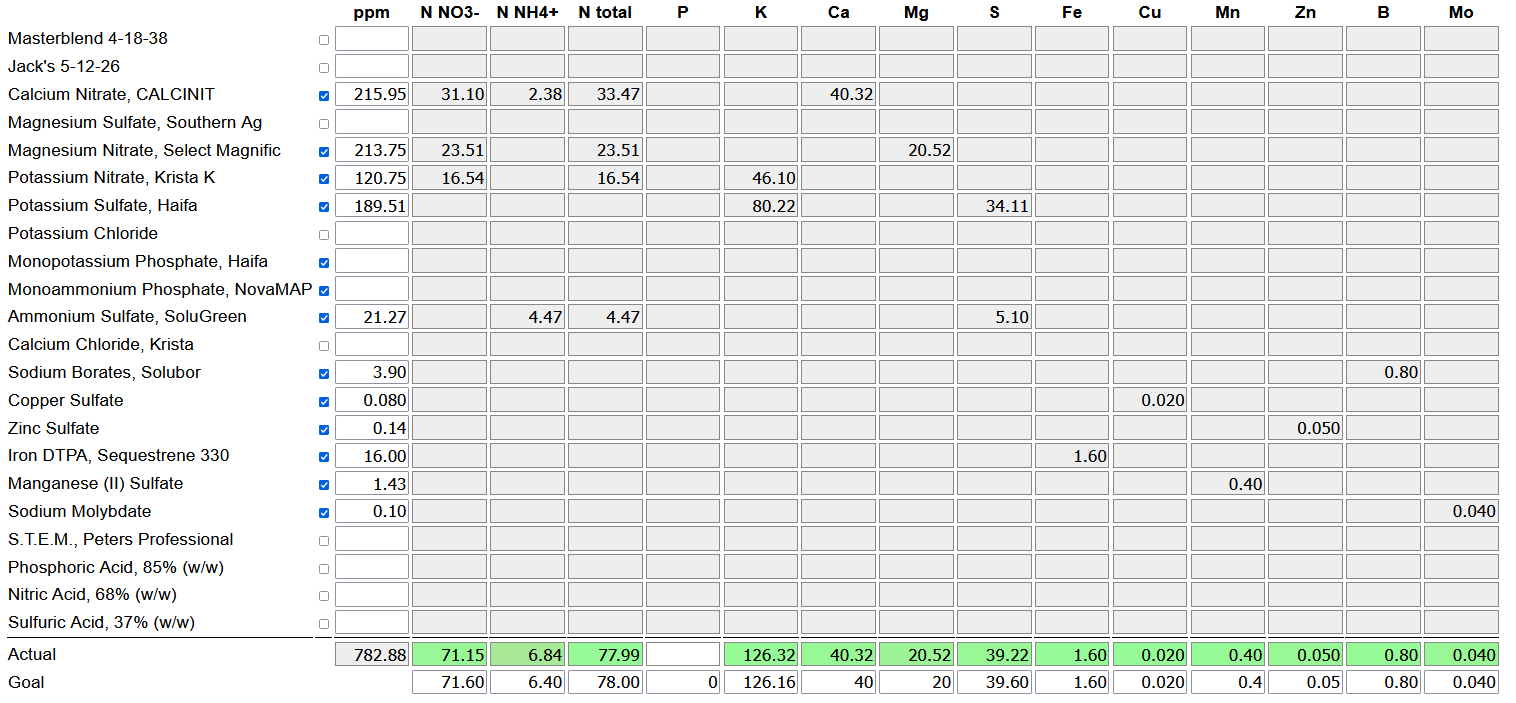

I then set all the ingredient inputs to zero, and un-checked all the ingredients containing chloride so the goal seek algorithm couldn't use them. I pressed the goal seek button, which returned a tentative recipe:

From there I rounded to the final recipe, and split the ingredients into two parts, in order to avoid precipitation of calcium phosphates or sulfate as discussed above. I mixed the following concentrates:

16.0 g Sodium Borate

0.4 g Sodium Molybdate

983.6 g Water

0.8 g Copper Sulfate

1.3 g Zinc Sulfate

14 g Manganese Sulfate

100 g Phosphoric Acid, 75% w/w

883.9 g Water

Part A9:

120 g Potassium Nitrate

190 g Potassium Sulfate

20 g Ammonium Sulfate

250 g micronutrient sodium stock

100 g micronutrient sulfate stock

water to make 1 gal

220 g Calcium Nitrate

220 g Magnesium Nitrate

16 g Iron DTPA

water to make 1 gal

I'm working mostly in metric here, but I made a gallon of each concentrate since I'm in the USA and can easily obtain gallon jugs.

The micronutrients are mixed in separate stock solutions, to save the effort of re-weighing them for each batch of nutrients. All solutions with micronutrient sulfates are acidified, since without that the copper, zinc and manganese will precipitate as the hydroxide or carbonate at high pH. (Even if no carbonate is added to a solution, it will absorb CO2 from air.) Most fertilizers would get that acidification naturally from the monopotassium phosphate (which is an acid salt), but here none is present. Sulfuric acid would be better, but I had phosphoric at hand and it seems to work.

The stock solution measurements are given by weight and not volume, since I have an accurate scale but no accurate liquid measures. The final Part A and Part B concentrates are made up to a specified weight/volume, not weight/weight, since they'll be dosed by volume.

These concentrates should provide the specified ppm of each element at a volume ratio of 1:220, since 220 gal ~ 1000 L. In practice my automated dosing system dilutes using peristaltic pumps, which aren't precisely calibrated so I just watch the EC10. This means that I don't exactly know the absolute concentration, but the relative element ratios are fixed.

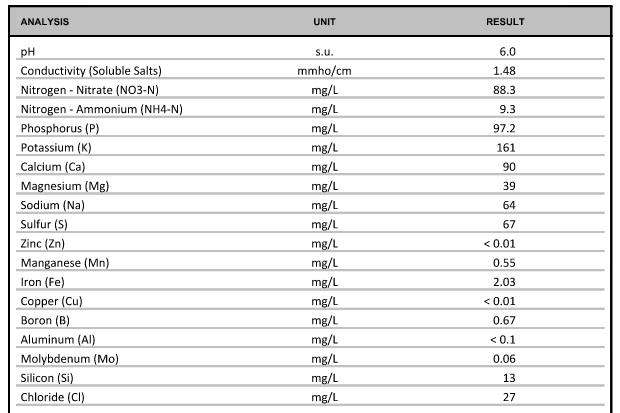

I sent a sample of nutrient solution for analysis by A&L Great Lakes Laboratories, as a quality control check to confirm (a) that I hadn't made a careless mistake while blending, (b) that my suppliers had actually sent me the right chemicals, and (c) that my tap water actually met the specifications on my local utility's website. I paid $45, and I got the following back:

This includes the contributions of both my nutrients and the source water. It's mostly as expected, a little stronger than my design but everything scaled up ratiometrically11. P is very high12, but it was even higher with the Masterblend. I'm not sure why the Cu and Zn ended up below their limit of detection; I was concerned that something was still precipitating, but I don't see any sediment. I'm hoping their limit of detection was just slightly higher than the claimed 0.01 ppm. Sodium and chloride are both high, but I'm pretty sure that's just my source water and not impurities in my fertilizer salts.

So I'm basically pleased with my recipe. I'm growing a few plants as a final test, and if those continue to look good I'll switch all my systems to the new recipe within a couple months. I don't suggest copying this recipe directly, since your water and growing goals are likely different from mine; but my intent here is to provide a rough template for the process and considerations required to develop a fertilizer customized for your own needs.

First published Nov 2021, updated Jan 2022: The original version of this article used citric acid to acidify the nutrients and stock solution. This worked, but I got filamentous solids after about a month, which I suspect were fungi eating the citrate. I've switched to phosphoric acid and seen no more trouble. The test grows went well, with good yield and no obvious deficiencies. All my previous grows with the Masterblend showed rising EC with time, while this one showed falling, implying an improved match between the ions in the solution and the ions taken up by the plants. I'm now running my complete automated system with these nutrients and pleased with the growth.

Footnotes

-

Or 17 counting nickel for urease, and certain rare plant species need additional elements. It's almost never necessary to consider any elements beyond those 16, though. ↩

-

Actually it's percent N directly, but it's percent equivalent P2O5 and K2O. This doesn't mean the fertilizers actually contain phosphorus pentoxide or potassium oxide; the percent is just the concentration of those compounds to achieve the same percent P and K. This is an unfortunate piece of historical confusion, and some fertilizer vendors now include the actual percent P and K elsewhere on the label too. ↩

-

So 4% N, 18% P2O5 equivalent, 38% K2O equivalent. ↩

-

Some vendors provide one-part nutrients intended for use with hard water, where the source water supplies all the calcium. These can work, but risk calcium deficiency if the water isn't hard enough. Some vendors also provide solid one-part nutrients including calcium, but these may be tricky or impossible to dissolve fully. ↩

-

Nothing fundamentally stops the blend from including more magnesium, since there's no precipitation problem like with the calcium. Their goal might have been to allow growers with source water high in magnesium to decrease the magnesium sulfate dose to offset. ↩

-

Note that in water chemistry, alkalinity doesn't just mean "high pH". Very roughly, alkalinity is a measure of the total amount of strong acid required to bring the pH down to a particular level, which is determined by various factors including the carbonate buffer system. Two solutions could have the same pH, but different alkaliniity. ↩

-

Sulfuric acid or nitric acid would have a more favorable effect on the nutrient profile, but they're more and much more dangerous respectively. Citric acid would have no effect on the nutrient profile, but it breaks down upon contact with the plants or reservoir microbiota, becoming ineffective as quickly as within hours. ↩

-

Papers studying plant response to those micronutrients generally show a small increase in yield as those increase, followed by a steep decrease after the toxic level. So running at optimal levels seems like it trades a small benefit (if we get the dose exactly right) against the risk of a big problem (if we overshoot). That didn't seem worth it for me. ↩

-

The literature seems inconsistent on whether the part with the calcium is Part A or Part B; I've seen it both ways. ↩

-

The solution electrical conductivity, in units like microsiemens per cm, uS/cm. This is used as a rough indication of the concentration of nutrient solutions, since that EC is roughly linearly proportional to the total dissolved content of ionic stuff. The scale factor varies with the specific ions, though. Instruments to measure EC are readily available, starting at just a few dollars. Many EC meters will also read out in "ppm", but they're actually just multiplying EC by a constant scale factor that's not exactly correct unless you're measuring pure NaCl solution (for those using 500 ppm/(mS/cm)) or pure KCl (for 700). This means the "true ppm" as calculated from the actual mg/L dosed and the "EC meter ppm" will be different, and the "EC meter ppm" may also be different with different meters. That's all pretty confusing, so I prefer to work in EC directly. ↩

-

For example, target total nitrogen was 78 ppm and they measure 88 + 9 = 97 ppm, 24% higher. Target potassium was 126 ppm and they measure 161 ppm, 28% higher, so a similar ratio. ↩

-

A professional would use sulfuric or nitric acid, but I don't want that in my apartment. It's also possible to remove the alkalinity in the water by reverse osomosis instead of neutralizing it with acid, and that would solve the problem completely. Household RO systems work, but generate perhaps three gallons of waste per gallon purified. Agricultural RO systems use pumps to achieve much higher pressure and thus better waste ratio, but they're designed for users well above my scale. ↩