Make a new folder off your home directory and clone the GitHub repo

$ cd ~

$ mkdir isc && cd isc

$ git clone https://github.com/infoscout/python-bootcamp.gitNext, open and add the python-bootcamp project to your IDE of choice. Once that is complete fire up the python interpreter and we can begin!

One of the most distinctive features of Python is its use of indentation to mark blocks of code. Most programming languages use certain characters or keywords to group statements

begin ... end

do ... end

{ ... }

if ... fi

However Python uses a different principle, indentation, to signify code blocks.

So how does this work? All statements that have the same amount of indentation (white space) to the left belong to the same block of code. Consider the following hypothetical program

if action == 'login':

print "Logging you in..."

print "Success!"

else:

print "Doh!"

print "Complete"

The first two print statements have the same indentation and therefore are part of the same code block. Each line in a code block will be executed sequentially so if action equals 'login' then 'Logging you in...' will print first followed by 'Success!'.

Regardless of what action equals, 'Complete' will be printed last because it is the final code block in the program.

More formerly speaking, leading whitespace (spaces and tabs) at the beginning of a logical line is used to compute the indentation level of the line, which in turn is used to determine the grouping of statements.

Similar to any other programming language or application (eg C++, Java, Excel) Python has a defined list of reserved identifiers, or keywords of the language, that should not be used when creating objects, variables, attributes.

The most important ones are listed here:

>>> import builtins

>>> dir(builtins)

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError', 'BaseException', 'BufferError',

'BytesWarning', 'DeprecationWarning', 'EOFError', 'Ellipsis', 'EnvironmentError',

'Exception', 'False', 'FloatingPointError', 'FutureWarning', 'GeneratorExit', 'IOError',

'ImportError', 'ImportWarning', 'IndentationError', 'IndexError', 'KeyError',

'KeyboardInterrupt', 'LookupError', 'MemoryError', 'NameError', 'None', 'NotImplemented',

'NotImplementedError', 'OSError', 'OverflowError', 'PendingDeprecationWarning',

'ReferenceError', 'RuntimeError', 'RuntimeWarning', 'StandardError', 'StopIteration',

'SyntaxError', 'SyntaxWarning', 'SystemError', 'SystemExit', 'TabError', 'True',

'TypeError', 'UnboundLocalError', 'UnicodeDecodeError', 'UnicodeEncodeError',

'UnicodeError', 'UnicodeTranslateError', 'UnicodeWarning', 'UserWarning', 'ValueError',

'Warning', 'ZeroDivisionError', '__builtins__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__future_module__',

'__name__', '__package__', '__path__', 'abs', 'absolute_import', 'all', 'any', 'apply',

'ascii', 'basestring', 'bin', 'bool', 'buffer', 'bytearray', 'bytes', 'callable', 'chr',

'classmethod', 'cmp', 'coerce', 'compile', 'complex', 'copyright', 'credits', 'delattr',

'dict', 'dir', 'divmod', 'enumerate', 'eval', 'execfile', 'exit', 'file', 'filter',

'float', 'format', 'frozenset', 'getattr', 'globals', 'hasattr', 'hash', 'help', 'hex',

'id', 'input', 'int', 'intern', 'isinstance', 'issubclass', 'iter', 'len', 'license',

'list', 'locals', 'long', 'map', 'max', 'memoryview', 'min', 'next', 'object', 'oct',

'open', 'ord', 'pow', 'print', 'property', 'quit', 'range', 'raw_input', 'reduce',

'reload', 'repr', 'reversed', 'round', 'set', 'setattr', 'slice', 'sorted', 'staticmethod',

'str', 'sum', 'super', 'sys', 'tuple', 'type', 'unichr', 'unicode', 'vars', 'xrange', 'zip']

Don't get too hung up on this topic but just know that they have special meanings within the Python interpreter and should be avoided as a name when declaring your own object.

Functions are a critical part of any programming language and their main purpose is to bundle a set of code.

It organizes code that you may want to reuse elsewhere in your codebase or is a single action that should be contained within a block. They provide modularity for your applications and significant code reuse.

The syntax for defining/creating functions uses the def keyword followed by the name of the function along with any optional parameters/arguments

Here are a few examples for defining and calling functions

# function that takes no parameters

>>> def shout():

... print "Hello InfoScouters!"

>>>

>>> shout()

Hello InfoScouters!

>>>

# function that takes one parameter

>>> def last_name(name):

... print "My last name is {lname}".format(lname=name)

>>>

>>> last_name('Sobchak')

My last name is Sobchak

>>>

>>> last_name('scott')

My last name is scott

>>>

For the most part in this course you will be writing code within functions that have already been defined but don't contain any logic

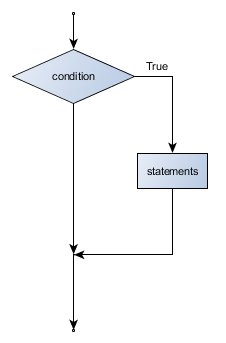

Conditional statements give us the ability to check conditions and change the behavior of the code/program at execution time.

Nearly every program contains these conditional statements and they take the form of boolean expressions. Here is a simple example:

>>> company = 'awesome'

>>>

>>> if company == 'awesome':

... print 'I work for an awesome company'

>>>

And here is another example that uses the common approach of if/else flow

>>> beers_remaining = 0

>>> if beers_remaining > 0:

... print "We still have beers!"

... else:

... print "The party is over, get out!"

>>>

Regardless of the language, a software engineer can write, stylize, and format code in endless ways. As such it is really important to follow standards so that all team members can easily read your code.

It makes it cleaner, crisper, and easier to read and understand. Nobody likes to read text ThAt iS wRiTteN LiKe This and the same principle holds true for software development.

PEP 8 is the standard (although not the only one) for writing pythonic code and it was created so python developers could adopt conventions for writing more readable code.

Do I need to memorize the entire PEP 8 standard? Good news... you don't. There are plenty plugins and command line tools that will check if your code is compliant with the PEP 8 style guide, and even fix some for you.

>>> a = 42

>>> a

42

>>> b = 99

>>> print b * 4

396

>>>

>>> a = 'Hello'

>>> print a

Hello

>>> s1 = 'InfoScout'

>>> s2 = ' is awesome'

>>> print s1 + s2

InfoScout is awesome

>>>

There are a number of methods available for string objects

>>> s = ' Puerto Vallarta '

>>> len(s)

21

>>> s.lower()

' puerto vallarta '

>>> s.strip()

'Puerto Vallarta'

>>> s.lower().strip()

'puerto vallarta'

>>>

What other methods are available to strings (or any object)? Use the very helpful dir() and help() commands

>>> z = 'baseball'

>>> dir(z)

['__add__', '__class__', '__contains__', '__delattr__', '__doc__', '__eq__',

'__format__', '__ge__', '__getattribute__', '__getitem__', '__getnewargs__',

'__getslice__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__le__', '__len__', '__lt__',

'__mod__', '__mul__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__',

'__repr__', '__rmod__', '__rmul__', '__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__',

'__subclasshook__', '_formatter_field_name_split', '_formatter_parser',

'capitalize', 'center', 'count', 'decode', 'encode', 'endswith', 'expandtabs',

'find', 'format', 'index', 'isalnum', 'isalpha', 'isdigit', 'islower', 'isspace',

'istitle', 'isupper', 'join', 'ljust', 'lower', 'lstrip', 'partition', 'replace',

'rfind', 'rindex', 'rjust', 'rpartition', 'rsplit', 'rstrip', 'split', 'splitlines',

'startswith', 'strip', 'swapcase', 'title', 'translate', 'upper', 'zfill']

>>> len

<built-in function len>

>>> len(z)

8

>>> help(len)

Help on built-in function len in module __builtin__:

len(...)

len(object) -> integer

Return the number of items of a sequence or collection.

(END)

However when in doubt if you can't find access to a particular method use google to find what you're looking for.

Strings are sequences of individual characters and can be accessed through the index notation

>>> a = 'Monty Python'

>>> a

'Monty Python'

>>> a[0]

'M'

>>> a[-1]

'n'

>>> a[4]

'y'

>>>

String "slicing" is a pythonic syntax to refer to sub-parts of sequences. The general format is as follows:

a[start:end] # items start through end-1

a[start:] # items start through the rest of the array

a[:end] # items from the beginning through end-1

a[:] # a copy of the whole array

And here it is in practice

>>> a = 'Monty Python'

>>> a[2:8]

'nty Py'

>>> a[1:]

'onty Python'

>>> a[:-1]

'Monty Pytho'

>>> a[:]

'Monty Python'

>>>

String formatting is the concept of concating different variables and data types to form a string. Format strings contain “replacement fields” surrounded by curly braces {}

>>> s = "Here {}, I have {} beers for you.".format("dana", 6)

>>> s

'Here dana, I have 6 beers for you.'

>>>

However the more pythonic way of string formatting would be using named placeholders

>>> address = '123 Main Street'

>>> city = 'San Francisco'

>>> s = 'I live on {address} in {city}'.format(address=address, city=city)

>>> s

'I live on 123 Main Street in San Francisco'

>>>

Here would be an example of how to format a float to 4 decimal places

>>> pi = 3.14159265359

>>> a = "Hooray for {pi:.4f}".format(pi=pi)

>>> a

'Hooray for 3.1416'

>>>

Lists in python are a type of "iterable" meaning it is a data structure that contains a stream of values. They can contain any sequence of data types but generally you would see the same data types.

Unlike the previous primitive data types that we explored, lists are "mutable" (i.e. they can be altered)

Here are a few ways to create lists

>>> list1 = []

>>> list2 = [42, 7, 3]

>>> list3 = ['infoscout', 'isc', True]

>>> list1

[]

>>> list2

[42, 7, 3]

>>> list3

['infoscout', 'isc', True]

>>>

Similar to string methods, there are a number of different methods you can call on an instance of a list

>>> list = [20, 5, 9]

>>> list

[20, 5, 9]

>>> list.append(50)

>>> list

[20, 5, 9, 50]

>>> a = list.pop()

>>> a

50

>>> list

[20, 5, 9]

>>>

>>> list1 = [4,5,6]

>>> list2 = [10, 20, 30]

>>> list1 + list2

[4, 5, 6, 10, 20, 30]

>>>

How do we look at each element in the list sequentially?

Iterating through iterables is a very common pattern in software development and we use the FOR and IN

clauses to look at each element in any type of iterable.

The general syntax is for var in list. Here are a few examples:

>>> numbers = [9, 235, 6, 0, 4]

>>> for number in numbers:

... print number

...

9

235

6

0

4

>>>

>>> name = 'InfoScout'

>>> for c in name:

... print c

...

I

n

f

o

S

c

o

u

t

>>>

>>> total = 0

>>> nums = [10, 20, 30]

>>> for num in nums:

... total += num

...

>>> print total

60

>>>

The easy way to sort a list is using the sorted construct.

>>> l = [12, 2, 99, 4, 8, 14]

>>> sorted(l)

[2, 4, 8, 12, 14, 99]

>>>

The sorted function also takes a handy optional parameter, reverse, that will sort an iterable in reverse

>>> l = ['l', 'p', 'a', 'c', 'g', 'b', 'm']

>>> sorted(l, reverse=True)

['p', 'm', 'l', 'g', 'c', 'b', 'a']

>>>

However what if you would like to perform a more complex sort?

Sorting takes an optional key= parameter that allows one to define custom sorting. The key function takes in 1 value

and returns 1 value, and the returned "proxy" value is used for the comparisons within the sort.

An example

>>> # sort by element length

>>> l = ['san francisco', 'boston', 'chicago', 'new york city']

>>> sorted(l, key=len)

['boston', 'chicago', 'san francisco', 'new york city']

>>>

It is important to note that the key= parameter can take any function as long as that function returns 1 value

So how would we sort a list of strings by their last character in ascending order?

>>> l = ['jsnl', 'ahxb', 'nla', 'uownk']

>>> def last_char(s):

... return s[-1]

...

>>> sorted(l, key=last_char)

['nla', 'ahxb', 'uownk', 'jsnl']

>>>

Dictionaries are a very common and powerful data structure in software. They are a key/value hash table that allows for extremely fast lookup and insertion.

The contents of a dictionary can be written as key:value pairs with braces {} and brackets [].

Strings, numbers, and tuples can be used for keys. Values accept any data type.

Here are a few examples for creating a dictionary:

>>> d = {}

>>> print d

{}

>>> d['fname'] = 'Dana'

>>> d['lname'] = 'Ford'

>>> print d

{'lname': 'Ford', 'fname': 'Dana'}

>>>

>>> z = {1: ['hello', 'word'], 9: ['abc']}

>>> print z

{1: ['hello', 'word'], 9: ['abc']}

>>>

To look up or set a value use brackets. Note that if the key you are looking for does not exist

then a KeyError exception will get raised

>>> d

{'lname': 'Ford', 'fname': 'Dana'}

>>> d['lname']

'Ford'

>>>

>>> d['city']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

KeyError: 'city'

>>> d['city'] = 'San Francisco'

>>> d

{'lname': 'Ford', 'city': 'San Francisco', 'fname': 'Dana'}

Dictionaries are like lists in that they are both iterables however dictionaries do not store items in order. Key/Value access is non-deterministic.

But like lists you can iterate through them. Since dictionaries have key and values you can iterate though the keys, values, or both (items).

>>> d

{'lname': 'Ford', 'city': 'San Francisco', 'fname': 'Dana'}

>>> for key in d.keys():

... print key

...

lname

city

fname

>>> for value in d.values():

... print value

...

Ford

San Francisco

Dana

>>> for key, value in d.items():

... print "Key: {key}. Value: {value}".format(key=key, value=value)

...

Key: lname. Value: Ford

Key: city. Value: San Francisco

Key: fname. Value: Dana

>>>

A set is a data structure that holds an unordered collection of objects with no duplicates. A basic use case of when to use a set would be removing duplicates in a list.

The syntax for sets use parenthesis ()

>>> s1 = set()

>>> s1

set([])

>>>

>>> s2 = set([1,2,3])

>>> s2

set([1, 2, 3])

>>>

>>> s3 = set([1,2,3,4,4,4,4])

>>> s3

set([1, 2, 3, 4])

>>>

Tuples are another data structure (iterable) that holds a stream of values.

A tuple uses the parenthesis () seperated by commas

>>> t = (1,2,3)

>>> t

(1, 2, 3)

>>> type(t)

<type 'tuple'>

>>> t[0]

1

>>>

>>> len(t)

3

Though tuples may seem similar to lists, they are often used in different situations and for different purposes. Tuples are immutable and usually contain a sequence of values that are different from each other.

>>> t = (10, 20, 30)

>>> t[0]

10

>>> t[0] = 1

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignment

>>>

One final note on tuples.

Python has a powerful feature that is known as "tuple unpacking" that allows a developer to unpack all of the elements of a tuple in a single line.

>>> t = ('San Francisco', 'California', 'United States')

>>> print t

('San Francisco', 'California', 'United States')

>>>

>>> city, state, country = t

>>> print city

San Francisco

>>> print state

California

>>> print country

United States

>>>

This does the equivalent of seven assignment statements, all on one easy line. One requirement is that the number of variables on the left must match the number of elements in the tuple.

The Python Standard Library is an extensive library that is distributed with every version of python. It offers a wide range of utilities, components, and frameworks. It also contains several modules that provide standardized solutions for many problems that occur in everyday programming.

Here are some of the most common libraries that are available:

>>> import datetime

>>> import re

>>> import math

>>> import os

>>> import sys

The Python Package Index (PyPI) is the official third party software repository for Python. It currently has over 100,000 projects is the central location for getting any library.

Here are some of the most common libraries that are available:

>>> import requests

>>> import boto

>>> import django

>>> import mock

The python requests library is a 3rd party library for handling HTTP requests. It is one of the most popular libraries within the python ecosystem (13MM downloads / month) and as their moto states, it was built for humans.

The library is easy to use because it abstracts and hides all of the lower level logic needed to build HTTP request objects. This allows the developer to focus on writing business logic and building features while not getting tied up with encoding query string parameters or form-encoding post data.

So how do we make a GET request using the requests library?

>>> import requests

>>> url = 'https://google.com'

>>> r = requests.get(url=url)

>>> print r.status_code

200

>>> print r.text

<!doctype html><html itemscope="" itemtype="http://schema.org/WebPage" lang="en"><head>

<meta content="Search the world's information, including webpages, images, videos and more.

Google has many special features to help you find exactly what you're looking for."

name="description"><meta content="noodp" name="robots"><meta content="text/html; charset=UTF-8"

http-equiv="Content-Type">

<meta content="/logos/doodles/2017/celebrating-50-years-of-kids-coding-5745168905928704.3-l.png"

itemprop="image"><meta content="Celebrating 50 years of Kids Coding" property="twitter:title">

<meta content="Celebrating 50 years of Kids Coding #GoogleDoodle"

property="twitter:description"><meta content="Celebrating 50 years of Kids Coding #GoogleDoodle"

property="og:description"><meta content="summary_large_image" property="twitter:card">

<meta content="@GoogleDoodles" property="twitter:site">

...

...

>>> dir(r)

['__attrs__', '__bool__', '__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__doc__', '__enter__',

'__exit__', '__format__', '__getattribute__', '__getstate__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__iter__',

'__module__', '__new__', '__nonzero__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__',

'__setstate__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', '_content',

'_content_consumed', '_next', 'apparent_encoding', 'close', 'connection', 'content', 'cookies',

'elapsed', 'encoding', 'headers', 'history', 'is_permanent_redirect', 'is_redirect',

'iter_content', 'iter_lines', 'json', 'links', 'next', 'ok', 'raise_for_status', 'raw', 'reason',

'request', 'status_code', 'text', 'url']

The csv module implements classes to read and write tabular data in CSV format. The csv module’s

reader and writer objects read and write sequences.

def read_movies():

import csv

import datetime

f = '/Users/df/isc/python-bootcamp/data/movies.csv'

with open(f, 'r') as csvreader:

reader = csv.reader(csvreader, delimiter=',')

for row in reader:

year_str = row[-1]

dt = datetime.datetime.strptime(year_str, '%Y')

print "Type = {t}. Value = {v}".format(t=type(dt), v=dt)The reader object will iterate over lines in the given csvfile

As we reviewed in lecture 1 a function (often interchanged with the word method although there are differences between the two) is a block of code that is:

- Organized

- Reusable

- Performs single action

These are not strict rules for writing functions but engineers should keep these characteristics in mind in order to build robust and well maintained code.

Let's walk through a few simple examples that illustrate these principles.

>>> def print_infoscout():

... print "Hello InfoScout"

>>>

>>> def print_sf():

... print "Hello San Francisco"

>>>

>>> def print_address():

... print "Hello 322 Ritch Street"

>>>

>>>

>>> print_infoscout()

Hello InfoScout

>>> print_sf()

Hello San Francisco

>>> print_address

Hello 322 Ritch Street

>>>

Generally speaking these 3 functions are organized and perform a single action however they are not that reusable. Can we make them more abstract to dynamically handle any input string?

>>> def print_string(s):

... print "Hello {s}".format(s=s)

>>>

>>> print_string('InfoScout')

Hello InfoScout

>>> print_string('San Francisco')

Hello San Francisco

>>> print_string('322 Ritch Street')

Hello 322 Ritch Street

>>>

The revised function is now much more powerful because it can be repurposed throughout a large codebase to handle any input string. This is abstraction and one of the core principles of any modern programming language.