| title |

|---|

Background |

Kangaroo rats’ hindlimbs and the jumping and landing motions are the center focus of this project. Many research projects have been done about the locomotion of the kangaroo rat [1]–[5]. Although there is not much literature studying just the landing and standing of such animals, it is expected that these papers can provide enough specifications and inspirations for the passive landing and standing robot to be designed. Table 1 lists the five sources on the candidate organism which were identified as the most useful for our project.

| Parameter | Reference |

|---|---|

| Jumping mechanics of desert kangaroo rats | [1] |

| Locomotion in Kangaroo Rats and Its Adaptive Significance | [2]* |

| Kangaroo rat locomotion: design for elastic energy storage or acceleration? | [3] |

| Functional capacity of kangaroo rat hindlimbs: adaptations for locomotor performance | [4]* |

| Elastic energy storage in the hopping of kangaroo rats Dipodomys spectabilis | [5]* |

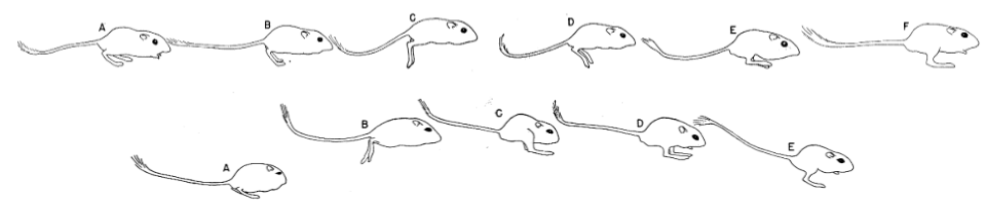

[2] introduces various locomotion modes of kangaroo rats through photographs, drawings, and text description. The most frequent locomotion of this species is bipedal hopping. When frightened, they tend to perform powerful, unpredictably, but controlled hops to avoid or escape from dangers. Other locomotions including quadrupedal hopping, climbing, and bipedal walking are less common. Additionally, the tail is an essential organ for balancing the movement. This paper confirms the mainly bipedal locomotion of the kangaroo rat, which suits well with the scope of our project. Its drawings and descriptions also provide detailed poses of the hopping.

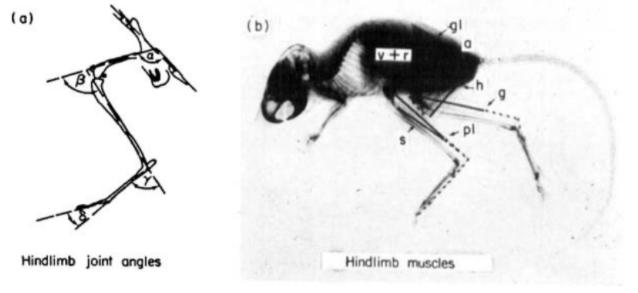

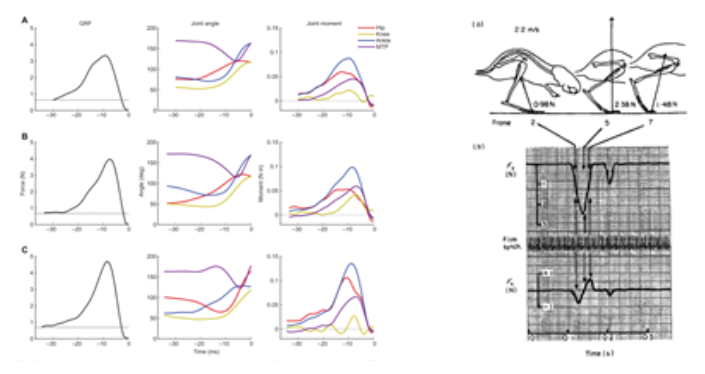

[5] dives deeper into the dynamics and energy of the hopping of kangaroo rats. It measures the force acting on the foot, speed, moment arms of the muscles and tendons, and limb angles by X-ray cinematography and force plate. Then, calculations and some assumptions are made to obtain the forces exerted by the ankle extensors and the overall length changes of the muscles and their tendons. Finally, more calculations and analysis conclude that the percentage recovery of energy by elastic storage during hopping is probably not more than 14% while the number for kangaroo is much higher reaching about 50%. This paper offers data about the hopping force and energy of the kangaroo rat and its bone, muscle, tendon structure. Also, it mentions the concept of Froude number that can determine whether animals of different sizes can hop in a kinematically similar fashion. This concept may also be useful if scaling of the robot is needed.

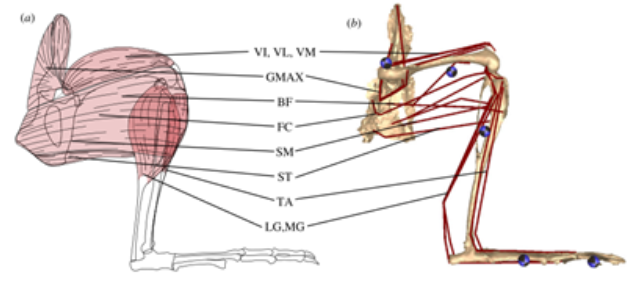

[4] is a more recent study about kangaroo rats and it is an example of how morphology balances the sometimes competing needs of hopping and jumping. It uses dissection data, a newly developed musculoskeletal model, and motion data to estimate the moment generating capacity of each muscle of the hindlimb over the range of motion. Although most of the hindlimb muscles architecture shows a strong positive relationship with the joint moment arms, there are exceptions for the ankle extensors which can generate high ankle moments over a big joint range with short fibre. This is mainly due to its biarticular nature that utilizes the motion of the knee and ankle during jumping to reduce the required strain. This paper provides detailed data and a model for 20 muscles and bones in the hindlimb of the kangaroo rat. It also reveals the genius use of biarticular muscle design that can be inspiring for the robot.

Eight closely related research articles were collected that pertain to the design of mechanisms involving landing of robots and listed in Table 2.

| Paper | Reference |

|---|---|

| Bioinspired jumping robot with elastic actuators and passive forelegs | [6] |

| A Survey of Bioinspired Jumping Robot: Takeoff, Air Posture Adjustment, and Landing Buffer | [7] |

| Design and dynamics analysis of a bio-inspired intermittent hopping robot for planetary surface exploration | [8] |

| Inertia matching manipulability and load matching optimization for humanoid jumping robot | [9] |

| Jumping robots: A biomimetic solution to locomotion across rough terrain | [10] |

| Landing Impact Analysis of a Bioinspired Intermittent Hopping Robot with Consideration of Friction | [11]* |

| A combined series-elastic actuator & parallel-elastic leg no-latch bio-inspired jumping robot | [12]* |

| Development of a biologically inspired hopping robot - ‘Kenken’ | [13]* |

In [11], an in depth analysis of landing dynamics and the impact process of a bio-inspired kangaroo robot was researched. A full kinematic description of the system was described to process how their robot absorbed energy during touchdown and the design process to achieve stability during this time. A particularly relevant topic of discussion in this paper described how the residual dynamics after the impact stage can be minimized so that the velocities and net moment of the device are within a desired threshold to maintain stability. In addition to minimizing the residual motion, another important consideration was that the impact process should be a viscous impact where velocity of the system decreases gradually then remains at zero. Although the paper did not quite achieve this result, they were able to minimize the bouncing that occurs post-impact.

In [12], a review of several existing jumping robots was compared. This research gives several examples of robots with successful landing buffering mechanisms and compares their specifications directly. The most notable comparisons between these robots was their energy storage capacity (J/Kg) which is interpreted as the capability to buffer the landing of the robot. Using readily available specifications like this can help inform the design of the robot that this team is proposing by providing a benchmark for achievable performance indicators for the proposed system.

In [13], a bio-inspired robotic platform was used to analyze running and hopping characteristics of their design. Although this robot’s passive mechanism is not as centralized around the ankle joint as the design that this team is proposing, the experimental results can be used to inform the design and tuning of parameters. Specifications on impact forces, empirically tuned spring stiffness and stabilization methods can be applied during the design process. The application of this data to the proposed passive ankle mechanism can be made more significant with slight modifications to their proposed kinematic equations to match the proposed system.

Lots of useful data is provided in the literature. Only more general data is listed in the table because the remaining ones are detailed and hard to summarize. For example, [4] contains body segment and individual muscle properties of the kangaroo rat hindlimb. [3] has the bone stress for the tibia and femur. It also has the peak ankle extensor muscles stress for hopping and jumping.

| Parameter | Units | Value Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total mass | kg | 0.072-0.120 | [1], [5] |

| Hopping peak ground force | N | 2.5 | [5] |

| Hopping positive work | J | 0.075 | [5] |

| Jumping height | m | 0.1-0.4 | [1] |

| Jumping peak ground force | N | 3-5 | [1] |

| Jumping power | W | 1-4.3 | [1] |

| Jumping total joint work | J | 0.1-0.3 | [1] |

Using the data presented in Section 3, several additional values can be found relating to requirements for landing. The total energy for a single jump can be calculated based on the mass and jump height. By making the assumption that the jumping peak ground force will act primarily in the vertical direction, the acceleration of a vertical jump can be found. Finally, the approximate time spent in contact with the ground at the beginning of a jump can be calculated. These calculated parameters are listed in Table 4.

| Parameter | Units | Value Range | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total jump energy | J | 0.071-0.47 | Total mass x Jumping height x g |

| Jumping acceleration | m/s^2 | 41.67 | Jumping peak ground force / Total mass |

| Jumping takeoff velocity | m/s | 1.2-3 | Jumping power / Jumping peak ground force |

| Jumping takeoff time | s | 0.02-0.3 | Jumping total joint work / Jumping power |

This information provides an estimate of the amount of energy that the constructed system will need to dissipate upon landing. It also would inform the selection of a motor if the jumping motion was actuated.

Figure 1 illustrates the pose of a kangaroo rat throughout its hopping gait. This figure demonstrates the motion of the leg that is used to jump, as well as the position of the leg shortly before and during landing. It also shows the use of a tail to stabilize the system during the gait.

Figures 2 and 3 show the structure of the bones, muscles, and tendons in a kangaroo rat’s leg. The geometry shown in these figures informed the development of the kinematic model discussed in Section 6.

Figure 4 provides information about the forces present in the leg and the positions of the leg joints throughout a hopping gait. This information informed the creation of the specifications table in Section 3, and will inform the tuning of the mechanism geometry.

Fig. 4. Ground reaction forces, joint angles, and joint moments during different stages of jumping [1, 5]

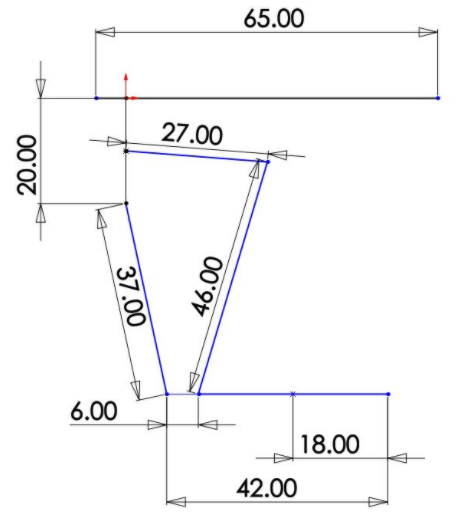

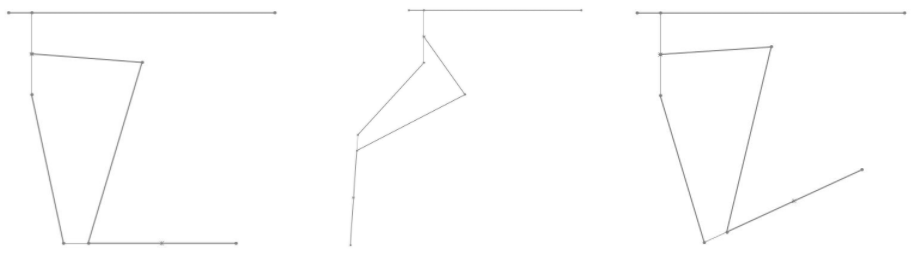

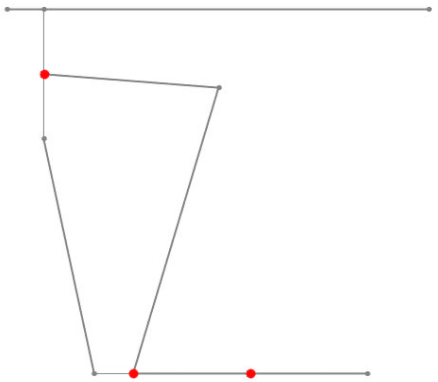

Based on the length and mass measurements provided in [4], the following model was created for our testing platform:

The body, pelvis, femur, tibia, midfoot, and toes are all modeled as rigid bodies. An additional linkage was added connecting the back of the midfoot to the bottom of the pelvis to create a 5-bar linkage with a range of motion that would normally be created by the muscles and tendons. The mean mass of a kangaroo rat is about 105.86gm (grams). The femur is 8.28gm, tibia 4.58gm, metatarsals 0.95gm, and toes 0.56gm, which are individually less than 1/10 of the total mass, meaning they can be approximated as massless. [4] The plan is to use materials that closely follow the actual mass of each rigid body. The model will not be powered by active actuators, instead, passive elastic laminate materials will be used to dampen the fall of the model. In figure 7, the red points represent the planned locations of torsional springs, though the exact locations are subject to change based on test results.

Between the pelvis-femur, tibia-midfoot, and midfoot-toe connections are laminate material connections that act as torsional springs to absorb the impact as the model falls to the ground.

- Discuss / defend your rationale for the size animal you selected in terms of your ability to replicate key features remotely with limited material selection.

The size of the kangaroo rat is easy to recreate using a small amount of materials but not too small as to require more precise manufacturing methods. The total length of the model body is 6.5cm. The total weight of the kangaroo rat is also only 106 grams, meaning the amount of material needed is quite small, which will help keep the project under the small budget for this course. The locomotion of the kangaroo rat also pairs nicely with our research question as the animal itself primarily moves in a bipedal fashion and is known for its jumping ability. This more closely aligns our results with the research question.

- Find a motor and battery that can supply the mechanical power needs obtained above. Consider that motor efficiencies may be as high as 95%, but if you can’t find it listed, assume you find a more affordable motor at 50-70% efficiency. Compare the mechanical watts/kg for the necessary motor and battery vs the animal’s mechanical power/mass above? Which one is more energy dense? Consider adding a motor for damping/changing spring coefficients/triggerting Otherwise talk about storing energy/dissipating energy mechanism

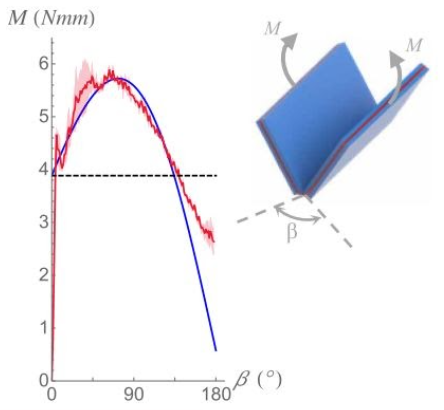

The planned laminate material is based on research done by Stefano Mintchev et al. A silicone membrane that is 0.3mm thick is surrounded by 0.5mm acrylic. By leaving a gap in the acrylic, the material is allowed to rotate and create an elastic torque. Depending on how much the silicone is stretched before being laminated, the force can be more or less. Figure 8 from Stefano Mintchev et al. shows the torque output plot as a function of angle for one prestech value. [14]

Based on the study’s particular stretch of the silicone, the torque created by the material is about 4N upon first being rotated. The torque reaches a maximum of 6N at about 90°. These exact torque outputs will be adjusted to suit our application by finding the ideal stretch to the silicone layer. The exact torque output for particular stretch proportions will need to be determined experimentally.

[1] M. J. Schwaner, D. C. Lin, and C. P. McGowan, “Jumping mechanics of desert kangaroo rats,” Journal of Experimental Biology, vol. 221, no. 22, 2018, doi: 10.1242/jeb.186700.

[2]* Jr. George A. Bartholomew and Jr. Herbert H. Caswell, “Locomotion in Kangaroo Rats and Its Adaptive Significance,” Journal of Mammalogy, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 155–169, 1951.

[3] A. A. Biewener and R. Blickhan, “Kangaroo rat locomotion: design for elastic energy storage or acceleration?,” The Journal of experimental biology, vol. 140, pp. 243–255, 1988.

[4]* J. W. Rankin, K. M. Doney, and C. P. McGowan, “Functional capacity of kangaroo rat hindlimbs: adaptations for locomotor performance,” Journal of the Royal Society Interface, vol. 15, no. 144, 2018, doi: 10.1098/rsif.2018.0303.

[5]* A. Biewener, R. M. N. Alexander, and N. C. Heglund, “Elastic energy storage in the hopping of kangaroo rats Dipodomys spectabilis,” Journal of Zoology, vol. 195, no. 3, pp. 369–383, 1981, doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1981.tb03471.x.

[6] U. Scarfogliero, C. Stefanini, and P. Dario, “Bioinspired jumping robot with elastic actuators and passive forelegs,” Proc. First IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatronics, 2006, BioRob 2006, vol. 2006, pp. 306–311, 2006, doi: 10.1109/BIOROB.2006.1639104.

[7] Z. Zhang, J. Zhao, H. Chen, and D. Chen, “A Survey of Bioinspired Jumping Robot: Takeoff, Air Posture Adjustment, and Landing Buffer,” Applied Bionics and Biomechanics, vol. 2017. Hindawi Limited, 2017, doi: 10.1155/2017/4780160.

[8] L. Bai, W. Ge, X. Chen, and R. Chen, “Design and dynamics analysis of a bio-inspired intermittent hopping robot for planetary surface exploration,” Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst., vol. 9, pp. 1–11, 2012, doi: 10.5772/51930.

[9] Z. Xu, T. Lü, and X. Wang, “Inertia matching manipulability and load matching optimization for humanoid jumping robot,” Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst., vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2012, doi: 10.5772/50916.

[10] R. Armour, K. Paskins, A. Bowyer, J. Vincent, and W. Megill, “Jumping robots: A biomimetic solution to locomotion across rough terrain,” Bioinspiration and Biomimetics, vol. 2, no. 3, 2007, doi: 10.1088/1748-3182/2/3/S01.

[11]* L. Bai, W. Ge, X. Chen, Q. Tang, and R. Xiang, “Landing Impact Analysis of a Bioinspired Intermittent Hopping Robot with Consideration of Friction,” Math. Probl. Eng., vol. 2015, pp. 1–12, 2015, doi: 10.1155/2015/374290.

[12]* C. Hong, D. Tang, Q. Quan, Z. Cao, and Z. Deng, “A combined series-elastic actuator & parallel-elastic leg no-latch bio-inspired jumping robot,” Mech. Mach. Theory, vol. 149, p. 103814, 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2020.103814.

[13]* S. H. Hyon and T. Mita, “Development of a biologically inspired hopping robot - ‘Kenken,’” Proc. - IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom., vol. 4, no. May, pp. 3984–3991, 2002, doi: 10.1109/robot.2002.1014356.

[14] Mintchev, S., Shintake, J., & Floreano, D. (2018). Bioinspired dual-stiffness origami. Science Robotics, 3(20), eaau0275. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.aau0275