In this exercise, we will learn how we can fix the code we write and validate it using tests. Then, we will talk about the steps needed to generate an artifact and deploy it to an environment. Last, we will review best practices and advanced topics that were inquired while doing the previous exercises.

The Microsoft's TypeScript Create React app project is a set of curated scripts to create React applications. By using this tool, we can bootstrap applications with the following built-in features:

- A ready-to-be-used development experience as similar to production as possible (

npm start). - A build script, configured and optimized for high performance (

npm run build). - A unit testing framework (npm run test) with code coverage already configured (

npm run test). - Latest tools, linter (npm run lint) and best practices for web development.

We used this tool to set up the apps in the previous exercises quickly. We are now going to extend this tool to allow a continuous delivery process.

Our app is already configured with TSLint, an extensible static analysis tool that checks TypeScript code for readability, maintainability and functionality errors.

As you've seen in the previous exercises, VSCode and most of the IDEs already know how to run it. Let's create a script to run these checks in our CI/CD pipeline:

-

Navigate to the project located in the begin folder of this exercise.

-

Run

npm ito install all its dependencies. -

Open the package.json file and find the scripts property.

-

Paste the following line to a new script named lint. Save the file.

"scripts": { "lint": "./node_modules/.bin/tsc && ./node_modules/.bin/tslint src/**/*.ts*", ... } -

Open a terminal and run

npm run lint. You should see no errors.What did we just do? We've just created an npm script that will run tsc (the compiler) and tslint (the static checker) for all the .ts and .tsx files inside the src folder. All errors you see before in VSCode are generated by running these two tools behind the scenes, per file. This script will run for all your files, and it will output all the errors you need to fix before moving forward.

Of course, to understand the full power of this tool, we need to generate a few errors.

-

Open the src/Home/Home.tsx file.

-

In line 15, rename the

handleItemClickmethod tohandleItemClicks. Notice that an error is present in line 33. -

Now, execute

npm run lint. You should see an error like the following: -

Undo the change and now change the modifier of the

renderProducts()method to private. You will see a bunch of errors related to the order of the class members. -

The good thing about these tools is that they can fix some errors automatically. Try this by either clicking the light bulb and selecting the Fix this option or by running

npm run lint -- --fix.

Note: If you want to know more about the rules that are enforced in the static analysis, you can search the rulesets defined in the extends property of the tslint.json. For instance, these are the rules defined for the tslint-react ruleset.

Pro tip! Your newly created script will help you to fix a significant amount of annoying issues at once.

Unit testing your code is just one command away: npm run test. By running this, you will execute Jest, the de-facto unit testing utility for React applications. This tool will execute all tests inside the *.test.ts or *.spec.ts files. We already have one test in place, App.test.tsx, let's see how it works:

-

In the root folder of the exercise, run

npm run test. It won't work as you haven't set up anything yet. -

Now, with

npm run teststill running, replace the entireit()method of the src/components/App/App.test.tsx file with the following:it("returns the proper page", () => { const app = new App({ pathname: "/" }); const result = app.getPages(); expect(result.length).toBe(1); expect(result[0].name).toBe("Home"); expect(result[0].url).toBe("/"); });

You should see now a green result for your tests suite.

Have you noticed? Unit testing in the UI is pretty similar to what you do in the backend. This applies to almost all methods in your classes. The only difference resides in the extra step you need to validate in the React components, the rendering phase.

Consider the <ShoppingCart /> component:

- It is instantiated with the items in the cart, like

<ShoppingCartStatus items={items} />. - If

itemsis undefined or there are no items, it should render an empty message. - If there are

items, it should render all of them.

To test the component, we have two options: render your component in a browser or simulate the rendering with a JavaScript tool like Enzyme (faster). Let's see it in action.

-

Install Enzyme and other dev dependencies by running

npm i -D enzyme @types/enzyme enzyme-adapter-react-16 @types/enzyme-adapter-react-16 react-test-renderer.Note: We've just installed

enzymeand the package with its declaration files,@types/enzyme. The other two packages are needed to configure Enzyme correctly, as we will see in the next step. -

Now create the file src/setupTests.ts that will be automatically loaded when running tests. This file will configure Enzyme to work with React 16.

import * as enzyme from "enzyme"; import * as Adapter from "enzyme-adapter-react-16"; enzyme.configure({ adapter: new Adapter() });

-

Last, go to the src/components/ShoppingCart folder and create a test file named ShoppingCart.test.tsx.

-

Paste the following

importstatements inside the newly created file:import * as React from "react"; import { shallow } from "enzyme"; import ShoppingCart from "./ShoppingCart";

Note:

shallowis a function that allows you to test your component as a unit, by executing a shallow rendering of it (and not rendering its children React components). You can learn more about it here/ -

Let's add our first test to validate that the

<ShoppingCart />component will render an empty message if it doesn't receive items. If you don't have Jest running in watch mode by now, execute it by runningnpm run test.it("renders the empty state if there are no items", () => { const wrapper = shallow(<ShoppingCart />); expect(wrapper.find(".shopping-cart-empty").exists()).toBeTruthy(); expect(wrapper.find(".shopping-cart-empty").text()).toBe("No items"); });

Check that this test passes before going to the next step.

Now, we'll add a test to validate if items are rendered as they should, and all the DOM elements are filled with the proper information.

-

For this, create the following empty test case:

it("renders items", () => { const items = [{ id: "1", name: "test-1", price: "$10", imageUrl: "imageUrl" }, { id: "2", name: "test-1", price: "$10", imageUrl: "imageUrl" }]; });

-

Below the

itemsarray, add the following lines to validate that, when rendered with items, the<ShoppingCart />component doesn't render the empty message and, instead, it renders the shopping cart items.it('renders items', () => { ... const wrapper = shallow(<ShoppingCart items={items} />); expect(wrapper.find('.shopping-cart-empty').exists()).toBeFalsy(); const shoppingCartItems = wrapper.find('.shopping-cart-items'); expect(shoppingCartItems.exists()).toBeTruthy(); });

-

Finally, add this code to validate that each value of the shopping cart items are properly rendered:

it('renders items', () => { ... shoppingCartItems.find('.shopping-cart-item').map((shoppingCartItem, index) => { expect(shoppingCartItem.exists()).toBeTruthy(); expect(shoppingCartItem.key()).toBe(items[index].id); expect(shoppingCartItem.find('.shopping-cart-item-name').text()).toBe(items[index].name); expect(shoppingCartItem.find('.shopping-cart-item-price').text()).toBe(items[index].price); expect(shoppingCartItem.find('.shopping-cart-item-image').prop('src')).toBe(items[index].imageUrl); }); });

If you are not executing Jest in your terminal, validate all suites pass by running

npm run test.

Finally, Jest has a way to record calls to a function, just like a sinon spy, named mocked functions. To play with this feature, create a new test to validate that the onItemRemove() function is called when removing an item.

-

Start by adding the following empty test case:

it("calls onItemRemove when an item is removed", () => { const items = [{ id: "1", name: "test-1", price: "$10", imageUrl: "imageUrl" }, { id: "2", name: "test-1", price: "$10", imageUrl: "imageUrl" }]; });

-

Set up the mocked function and initialize the wrapper with the

itemsand theonItemRemoveSpyvalues as props.it('calls onItemRemove when an item is removed', () => { ... const onItemRemoveSpy = jest.fn(); const wrapper = shallow(<ShoppingCart items={items} onItemRemove={onItemRemoveSpy} />); });

Note: Mock functions make it easy to test the links between code by erasing the actual implementation of a function, capturing calls to the function (and the parameters passed in those calls) and allowing test-time configuration of return values. If you want to know more about this function, see here.

-

Simulate a

clickof a remove link and validate that the mocked function is called afterwards with this code:it('calls onItemRemove when an item is removed', () => { ... const evt = { preventDefault: () => {}, currentTarget: { dataset: { id: items[0].id } } }; wrapper.find('.shopping-cart-item-remove').first().simulate('click', evt); expect(onItemRemoveSpy).toBeCalledWith(items[0]); });

Note: As its name states, simulate is a very useful tool to simulate events and user interaction. If you review the

ShoppingCart.handleItemRemove()method, you will notice that it uses theevtobject internally twice. To execute our tests, We need to mock this object too.

Pro tip! Always the Jest's watch mode to fix your tests on the fly. Jest will automatically run as soon as it detects changes.

When running the project with npm run start, we want our code to be executed as fast as possible, and having development-time tools that will simplify troubleshooting, like source maps. On the opposite, when creating our production build, we want our code to be as fast and small as possible, something that specific optimizations like minification can accomplish.

We typically build our app using a development and a production mode, generating different artifacts to cover different needs. In our case, we create our artifact by running npm run build. This script will run several checks and compilation processes to generate a curated, production-ready artifact that we can use to deploy to any environment.

-

Open a terminal in the root folder of the app and execute

npm run build. -

Fix all the errors until you get something like this:

Note: An static application was generated in the build folder. Your business logic files were merged into a single file per type, in this case, a single JS and CSS file.

-

serve is a simple command-line web server built. Install it by running

npm i -g serve. -

When it is installed, test your app by running

serve -s build. -

Navigate to http://localhost:5000 and validate that your app is running just like it was when you executed

npm run start. -

Open the Network tab in the Developers console and refresh the page. Take a look at the requested files.

As shown, the artifact generated is ready to be used by any web server, like Amazon CloudFront or event a Node Express Server.

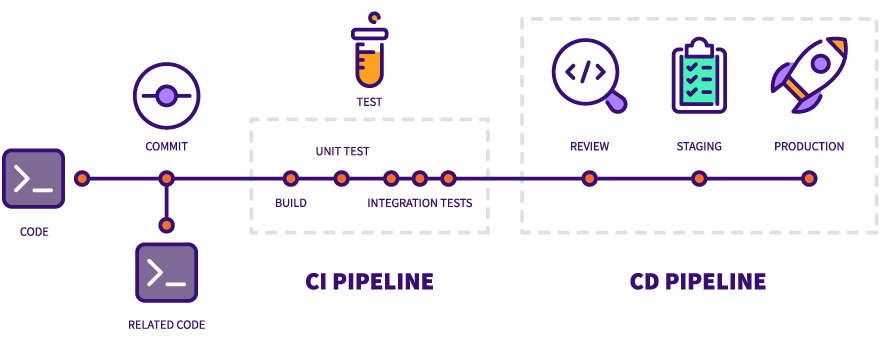

These scripts an be orchestrated to progressively validate our code, that will ultimately be deployed into a service. Several automation servers can execute these and other scripts every time we perform specific actions, like opening a PR or merging code into master.

As an example, below you could find a file that Jenkins server could run to validate your code, generate an artifact and deploy it to a CDN, stopping the pipeline if any of these scripts fail.

node {

stage('Run lint') {

run 'npm run lint'

}

stage('Run tests') {

run 'npm run test'

}

stage('Build artifact') {

run 'npm run build'

}

stage('Upload artifact to CDN') {

...

}

}In this section, we will present some topics that we think they worth a brief discussion and analysis. We have seen most of them in the previous exercises, but we couldn't grasp their meaning.

The destructuring assignment syntax is a JavaScript expression that makes it possible to unpack values from arrays, or properties from objects, into distinct variables. In conjunction with the object spread operator (still in proposal) it gives us a lot of flexibility to pick up values and copy them to variables.

let a, b, rest;

// This assigns 10 to variable 'a', 20 to variable 'b' [30,40,50] to variable rest

[a, b, ...rest] = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50];const props = { id: 1, name: 'something', items: [1, 2, 3], color: 'red' };

// This assigns props.id and props.name to variable 'id' and 'name'

// and the other properties to variable rest (i.e. an { items: [1, 2, 3], color: 'red' }).

const { id, name, ...rest } = props;

// And it's super helpful to define variables at the beginning of a function

const myFunction = ({ id, name, ...rest}) => {

...

};

myFunction(props);In JavaScript (and other languages), when a condition is evaluated (either && or ||), the second argument is evaluated only if the first argument does (not) satisfy the given condition. This is called short-circuit evaluation and it is useful to decide whether to render a component or not.

Instead of doing this:

const userInfo = ({ user }) => {

if (!user) {

return null;

}

return <User user={user} />;

};We could to this:

const userInfo = ({ user }) => {

return user && <User user={user} />;

};We haven't talked a lot about CSS. What we can say here is that the idea of global CSS class names goes against React composition. The most used technique in React is to localize your CSS classes in your React components, in a way that your CSS classes will only style your component. For this, one of the tools that we could use is CSS Modules.

A CSS Module is a CSS file in which all class names and animation names are scoped locally by default.

/* style.css */

.success {

color: green;

}When importing the CSS Module from a JS Module, it exports an object with all mappings from local names to global names.

import React from "react";

import styles from "./style.css";

const SuccessMessage = ({ props }) => <div className={styles.success}>Success!!</div>;

export default SuccessMessage;By localizing your CSS class names (i.e., renaming them to be unique), this library guarantees a modular and reusable CSS:

- No more conflicts.

- Explicit dependencies.

- No global scope.

React &andRedux don't have opinions on how you put files into folders. There are a few common strategies that have their own props/cons:

-

Rails-style: separate folders for “actions”, “constants”, “reducers”, “containers”, and “components”. This is the most common strategy in startup guides and documentation, but it doesn't age well, nor it helps you while refactoring a component and its actions/reducers.

/src /actions products.js user.js special-offers.js ... /reducers products.js user.js special-offers.js ... /containers Home.tsx ShoppingCart.tsx /components Home.tsx ShoppingCart.tsx Topbar.tsx Sidebar.tsx Deals.tsx /tests ... -

Domain-style: separate folders per feature or domain, possibly with sub-folders per file type. With this approach, you can group everything that makes sense into a single folder, and use the index.ts files to export what you want to expose. We do split React (components) and Redux (data domain), as the actions and reducers are usually used in more than one component.

/src /components /Home index.ts Home.tsx Home.container.tsx Home.tests.tsx /ShoppingCart index.ts ShoppingCart.tsx ShoppingCart.container.tsx ShoppingCart.tests.tsx /Topbar index.ts Topbar.tsx Topbar.tests.ts ... /domains index.ts /products index.ts actions.ts reducers.ts /user index.ts actions.ts reducers.ts /special-offers index.ts actions.ts reducers.ts ...

Note: For more information, see React file structure and Redux code structure documentation.

Redux suggests the use of two techniques to manipulate data:

Instead of storing something like this:

const blogPosts = [{

id: "post1",

author: { username : "user1", name : "User 1" },

body: "......",

comments: [{

id: "comment1",

author: { username : "user2", name : "User 2" },

comment: ".....",

}, {

id: "comment2",

author: { username : "user3", name : "User 3" },

comment: ".....",

}

]}, {

id: "post2",

...It suggests you manipulate what you receive from the backend and transform it into something like this:

{

"posts": {

"byId": {

"post1": {

"id": "post1",

"author": "user1",

"body": "......",

"comments": ["comment1", "comment2"]

},

"post2": {

...

}

},

"allIds": ["post1", "post2"]

},

"comments": {

"byId": {

"comment1": {

"id": "comment1",

"author": "user2",

"comment": ".....",

},

"comment2": {

"id": "comment2",

"author": "user3",

"comment": ".....",

},

...

},

"allIds": ["comment1", "comment2", "comment3", "commment4", "comment5"]

},

"users": {

"byId": {

"user1": {

"username": "user1",

"name": "User 1",

},

...

},

"allIds": ["user1", "user2", "user3"]

}

}This flat structure has a lot of benefits:

- Information is only present in a simple place, simplifying updates.

- The reducer logic will be much easier to read, as it has to deal with a simpler structure.

- The logic for retrieving or updating a given item is now more straightforward. We can directly look the item's id up in a couple of simple steps, without having to dig through other objects to find it.

Plus, A normalized state structure generally implies that more components are connected, and each component is responsible for looking up its data, as opposed to a few connected components looking up large amounts of data and passing all that data downwards. As it turns out, having connected parent components simply pass item IDs to connected children is a good pattern for optimizing UI performance in a React Redux application, so keeping state normalized plays a crucial role in improving performance.

Note: to avoid doing this by yourself, Redux suggests the use of Normalizr, that can flatten your nested structure if you give it the JSON schema.

Most React and Redux applications have a lot of logic to manipulate the state. This logic is often used in several components, and clearly, it is not part of their responsibilities. For instance, consider the getPages() method of the <App /> component.

public getPages() {

const { pathname } = this.props;

if (pathname === '/') {

return [{ name: 'Home', url: '/' }];

}

return pathname.split('/').map(item => ({

name: item ? item[0].toUpperCase() + item.slice(1).replace('-', ' ') : 'Home',

url: `/${item}`

}));

}For this type of methods that only manipulate the state, Redux suggests the use of selectors, which are simply functions that encapsulate this logic to be reused across your application. Making this a selector is simple, you only need to create a selectors.ts file and place it inside the proper data domain folder:

export const getPages = state => {

const { pathname } = this.state;

if (pathname === "/") {

return [{ name: "Home", url: "/" }];

}

return pathname.split("/").map(item => ({

name: item ? item[0].toUpperCase() + item.slice(1).replace("-", " ") : "Home",

url: `/${item}`

}));

};Then, consume this selector in your container component.

import { connect } from 'react-redux';

import { actions, selectors } from '../../domains';

import App from './App';

const mapStateToProps = (state: any) => ({

pathname: selectors.getPages(state),

...

});

...

export default connect(mapStateToProps, mapDispatchToProps)(App);There is a well-known library to generate selectors named Reselect, which provides a lot of goodies like computation of derived data, selectors composition and memoization.

import { createSelector } from "reselect";

const getVisibilityFilter = (state, props) => state.todoLists[props.listId].visibilityFilter;

const getTodos = (state, props) => state.todoLists[props.listId].todos;

const getVisibleTodos = createSelector(

[getVisibilityFilter, getTodos],

(visibilityFilter, todos) => {

switch (visibilityFilter) {

case "SHOW_COMPLETED":

return todos.filter(todo => todo.completed);

case "SHOW_ACTIVE":

return todos.filter(todo => !todo.completed);

default:

return todos;

}

}

);

export default getVisibleTodos;🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉