Mach-O is the native executable format of binaries in OS X and is the preferred format for shipping code. An executable format determines the order in which the code and data in a binary file are read into memory. The ordering of code and data has implications for memory usage and paging activity and thus directly affects the performance of your program.

A Mach-O binary is organized into segments. Each segment contains one or more sections. Code or data of different types goes into each section. Segments always start on a page boundary, but sections are not necessarily page-aligned. The size of a segment is measured by the number of bytes in all the sections it contains and rounded up to the next virtual memory page boundary. Thus, a segment is always a multiple of 4096 bytes, or 4 kilobytes, with 4096 bytes being the minimum size.

The segments and sections of a Mach-O executable are named according to their intended use. The convention for segment names is to use all-uppercase letters preceded by double underscores (for example, __TEXT); the convention for section names is to use all-lowercase letters preceded by double underscores (for example, __text).

There are several possible segments within a Mach-O executable, but only two of them are of interest in relation to performance: the __TEXT segment and the __DATA segment.

Table 1 lists some of the more important sections that can appear in the __TEXT segment. For a complete list of segments, see Mach-O Runtime Architecture.

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

__text |

The compiled machine code for the executable |

__const |

The general constant data for the executable |

__cstring |

Literal string constants (quoted strings in source code) |

__picsymbol_stub |

Position-independent code stub routines used by the dynamic linker (dyld). |

The __DATA segment contains the non-constant data for an executable. This segment is both readable and writable. Because it is writable, the __DATA segment of a framework or other shared library is logically copied for each process linking with the library. When memory pages are readable and writable, the kernel marks them copy-on-write. This technique defers copying the page until one of the processes sharing that page attempts to write to it. When that happens, the kernel creates a private copy of the page for that process.

The __DATA segment has a number of sections, some of which are used only by the dynamic linker. Table 2 lists some of the more important sections that can appear in the __DATA segment. For a complete list of segments, see Mach-O Runtime Architecture.

| Section | Description |

|---|---|

__data |

Initialized global variables (for example int a = 1; or static int a = 1;). |

__const |

Constant data needing relocation (for example, char * const p = "foo";). |

__bss |

Uninitialized static variables (for example, static int a;). |

__common |

Uninitialized external globals (for example, int a; outside function blocks). |

__dyld |

A placeholder section, used by the dynamic linker. |

__la_symbol_ptr |

“Lazy” symbol pointers. Symbol pointers for each undefined function called by the executable. |

__nl_symbol_ptr |

“Non lazy” symbol pointers. Symbol pointers for each undefined data symbol referenced by the executable. |

The composition of the __TEXT and __DATA segments of a Mach-O executable file has a direct bearing on performance. The techniques and goals for optimizing these segments are different. However, they have as a common goal: greater efficiency in the use of memory.

Most of a typical Mach-O file consists of executable code, which occupies the __TEXT, __text section. As noted in The __TEXT Segment: Read Only, the __TEXT segment is read-only and is mapped directly to the executable file. Thus, if the kernel needs to reclaim the physical memory occupied by some __text pages, it does not have to save the pages to backing store and page them in later. It only needs to free up the memory and, when the code is later referenced, read it back in from disk. Although this is cheaper than swapping—because it involves one disk access instead of two—it can still be expensive, especially if many pages have to be recreated from disk.

One way to improve this situation is through improving your code’s locality of reference through procedure reordering, as described in Improving Locality of Reference. This technique groups methods and functions together based on the order in which they are executed, how often they are called, and the frequency with which they call one another. If pages in the __text section group functions logically in this way, it is less likely they have to be freed and read back in multiple times. For example, if you put all of your launch-time initialization functions on one or two pages, the pages do not have to be recreated after those initializations have occurred.

Unlike the __TEXT segment, the __DATA segment can be written to and thus the pages in the __DATA segment are not shareable. The non-constant global variables in frameworks can have an impact on performance because each process that links with the framework gets its own copy of these variables. The main solution to this problem is to move as many of the non-constant global variables as possible to the __TEXT,__const section by declaring them const. Reducing Shared Memory Pages describes this and related techniques. This is not usually a problem for applications because the __DATA section in an application is not shared with other applications.

The compiler stores different types of nonconstant global data in different sections of the __DATA segment. These types of data are uninitialized static data and symbols consistent with the ANSI C notion of “tentative definition” that aren’t declared extern. Uninitialized static data is in the __bss section of the __DATA segment. Tentative-definition symbols are in the __common section of the __DATA segment.

The ANSI C and C++ standards specify that the system must set uninitialized static variables to zero. (Other types of uninitialized data are left uninitialized.) Because uninitialized static variables and tentative-definition symbols are stored in separate sections, the system needs to treat them differently. But when variables are in different sections, they are more likely to end up on different memory pages and thus can be swapped in and out separately, making your code run slower. The solution to these problems, as described in Reducing Shared Memory Pages, is to consolidate the non-constant global data in one section of the __DATA segment.

Brief description taken from Wikipedia:

Mach-O, short for Mach object file format, is a file format for executables, object code, shared libraries, dynamically-loaded code, and core dumps. A replacement for the a.out format, Mach-O offers more extensibility and faster access to information in the symbol table.

Mach-O is used by most systems based on the Mach kernel. NeXTSTEP, OS X, and iOS are examples of systems that have used this format for native executables, libraries and object code.

Mach-O doesn’t have any special format like XML/YAML/JSON/whatnot, it’s just a binary stream of bytes grouped in meaningful data chunks. These chunks contain a meta-information, e.g.: byte order, cpu type, size of the chunk and so on.

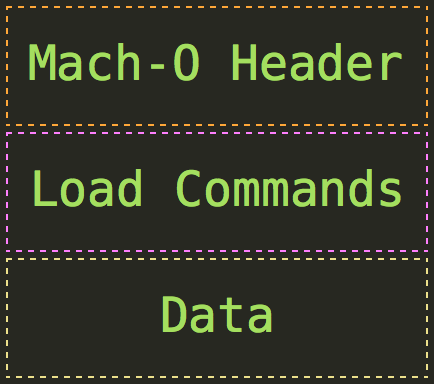

Typical Mach-O file (copy of the (now removed) official documentation) consists of a three regions:

- Header - contains general information about the binary: byte order (magic number), cpu type, amount of load commands etc.

- Load Commands - it’s kind of a table of contents, that describes position of segments, symbol table, dynamic symbol table etc. Each load command includes a meta-information, such as type of command, its name, position in a binary and so on.

- Data - usually the biggest part of object file. It contains code and data, such as symbol tables, dynamic symbol tables and so on.

Here is a simplified graphical representation:

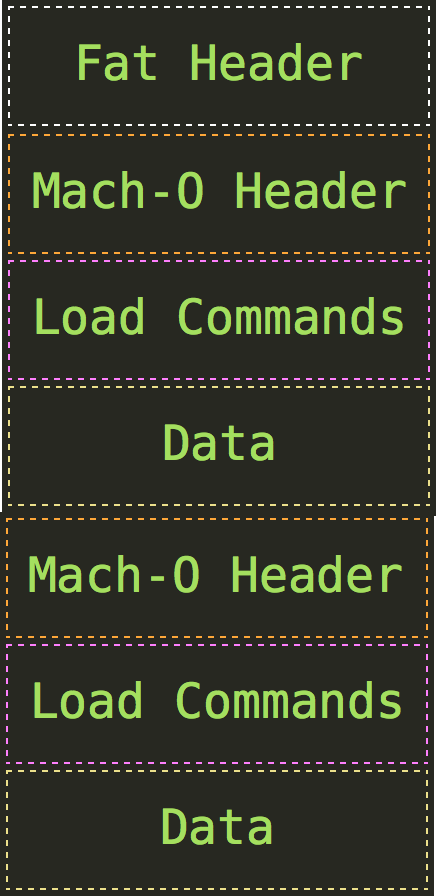

There are two types of object files on OS X: Mach-O files and Universal Binaries, also so-called Fat files. The difference between them: Mach-O file contains object code for one architecture (i386, x86_64, arm64, etc.) while Fat binaries might contain several object files, hence contain object code for different architectures (i386 and x86_64, arm and arm64, etc.)

The structure of a Fat file is pretty straightforward: fat header followed by Mach-O files:

OS X doesn’t provide us with any libmacho or something similar, the only thing we have here - a set of C structures defined under /usr/include/mach-o/*, hence we need to implement parsing on our own. It might be tricky, but it’s not that hard.

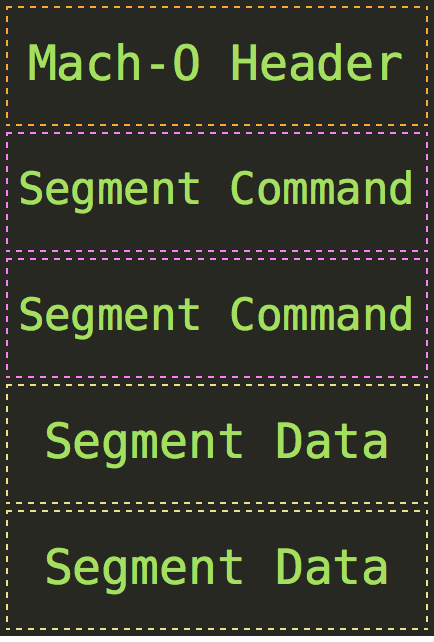

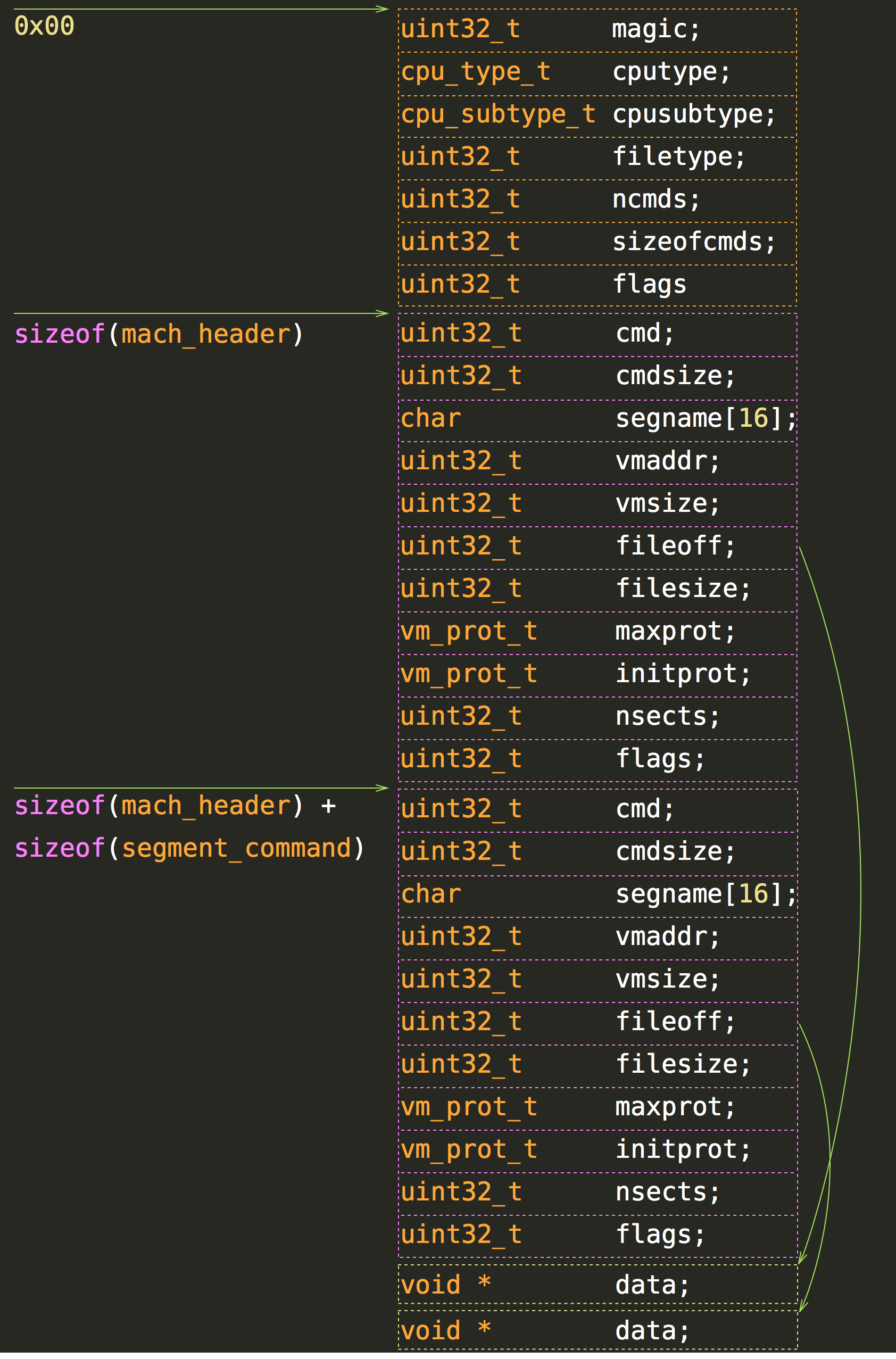

Before we start with parsing let’s look at detailed representation of a Mach-O file. For simplicity the following object file is a Mach-O file (not a fat file) for i386 with just two data entries that are segments.

The only structures we need to represent the file:

struct mach_header {

uint32_t magic;

cpu_type_t cputype;

cpu_subtype_t cpusubtype;

uint32_t filetype;

uint32_t ncmds;

uint32_t sizeofcmds;

uint32_t flags;

};

struct segment_command {

uint32_t cmd;

uint32_t cmdsize;

char segname[16];

uint32_t vmaddr;

uint32_t vmsize;

uint32_t fileoff;

uint32_t filesize;

vm_prot_t maxprot;

vm_prot_t initprot;

uint32_t nsects;

uint32_t flags;

};Here is how memory mapping looks like:

If you want to read particular info from a file, you just need a correct data structure and an offset.

Let’s write a program that’ll read mach-o or fat file and print names of each segment and an arch for which it was built.

At the end we might have something similar:

$ ./segname_dumper some_binary

i386

segname __PAGEZERO

segname __TEXT

segname __LINKEDITLet’s start with a simple ‘driver’.

There are at least two possible ways to parse such files: load content into memory and work with buffer directly or open a file and jump back and forth through it. Both approaches have their own pros and cons, but I’ll stick to a second one. Also, I assume that no one going to use the program in a wrong way, hence no error handling whatsoever.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <mach-o/loader.h>

#include <mach-o/swap.h>

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file);

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

const char *filename = argv[1];

FILE *obj_file = fopen(filename, "rb");

dump_segments(obj_file);

fclose(obj_file);

return 0;

}

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file) {

// Driver

}To read at least the object file header we need to get all the information we need: CPU arch (32 bit or 64 bit) and the Byte Order. But first we need to retrieve a magic number:

uint32_t read_magic(FILE *obj_file, int offset) {

uint32_t magic;

fseek(obj_file, offset, SEEK_SET);

fread(&magic, sizeof(uint32_t), 1, obj_file);

return magic;

}

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file) {

uint32_t magic = read_magic(obj_file, 0);

}The function read_magic is pretty straitforward, though one thing there might look weird: fseek. The problem is that whenever somebody read from a file, the internal _offset of the file changes. It’s better to specify the offset explicitly, to ensure that we read what we actually want to read. Also, this small trick will be useful later on.

Structures that represent object file with 32 and 64 bits are different (e.g.: mach_header and mach_header_64), to choose which to use we need to check file’s architecture:

int is_magic_64(uint32_t magic) {

return magic == MH_MAGIC_64 || magic == MH_CIGAM_64;

}

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file) {

uint32_t magic = read_magic(obj_file, 0);

int is_64 = is_magic_64(magic);

}MH_MAGIC_64 and MH_CIGAM_64 are ‘magic’ numbers provided by the system. Second one looks even more magicly than first one. Explanation is following.

Due to historical reasons different computers might use different byte order: Big Endian (left to right) and Little Endian (right to left). Magic numbers store this information as well: MH_CIGAM and MH_CIGAM_64 says that byte order differs from host OS, hence all the bytes should be swapped:

int should_swap_bytes(uint32_t magic) {

return magic == MH_CIGAM || magic == MH_CIGAM_64;

}

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file) {

uint32_t magic = read_magic(obj_file, 0);

int is_64 = is_magic_64(magic);

int is_swap = should_swap_bytes(magic);

}Finally we can read mach_header. Let’s first introduce generic function for reading data from a file.

void *load_bytes(FILE *obj_file, int offset, int size) {

void *buf = calloc(1, size);

fseek(obj_file, offset, SEEK_SET);

fread(buf, size, 1, obj_file);

return buf;

}Note: The data should be freed after usage!

void dump_mach_header(FILE *obj_file, int offset, int is_64, int is_swap) {

if (is_64) {

int header_size = sizeof(struct mach_header_64);

struct mach_header_64 *header = load_bytes(obj_file, offset, header_size);

if (is_swap) {

swap_mach_header_64(header, 0);

}

free(header);

} else {

int header_size = sizeof(struct mach_header);

struct mach_header *header = load_bytes(obj_file, offset, header_size);

if (is_swap) {

swap_mach_header(header, 0);

}

free(header);

}

free(buffer);

}

void dump_segments(FILE *obj_file) {

uint32_t magic = read_magic(obj_file, 0);

int is_64 = is_magic_64(magic);

int is_swap = should_swap_bytes(magic);

dump_mach_header(obj_file, 0, is_64, is_swap);

}Here we introduced another function dump_mach_header to not mess up ‘driver’ function. The next step is to read all segment commands and print their names. The problem is that mach-o files usually contain other commands as well. If you recall the first field of segment_command structure is a uint32_t cmd;, this field represents type of a command. Here is another structure provided by the system that we’ll use:

struct load_command {

uint32_t cmd;

uint32_t cmdsize;

};Besides all the information mach_header has number of load commands, so we can just iterate over and skip commands we’re not interested in. Also, we need to calculate offset where the header ends. Here is the final version of dump_mach_header:

void dump_mach_header(FILE *obj_file, int offset, int is_64, int is_swap) {

uint32_t ncmds;

int load_commands_offset = offset;

if (is_64) {

int header_size = sizeof(struct mach_header_64);

struct mach_header_64 *header = load_bytes(obj_file, offset, header_size);

if (is_swap) {

swap_mach_header_64(header, 0);

}

ncmds = header->ncmds;

load_commands_offset += header_size;

free(header);

} else {

int header_size = sizeof(struct mach_header);

struct mach_header *header = load_bytes(obj_file, offset, header_size);

if (is_swap) {

swap_mach_header(header, 0);

}

ncmds = header->ncmds;

load_commands_offset += header_size;

free(header);

}

dump_segment_commands(obj_file, load_commands_offset, is_swap, ncmds);

}It’s time to dump all segment names:

void dump_segment_commands(FILE *obj_file, int offset, int is_swap, uint32_t ncmds) {

int actual_offset = offset;

for (int i = 0; i < ncmds; i++) {

struct load_command *cmd = load_bytes(obj_file, actual_offset, sizeof(struct load_command));

if (is_swap) {

swap_load_command(cmd, 0);

}

if (cmd->cmd == LC_SEGMENT_64) {

struct segment_command_64 *segment = load_bytes(obj_file, actual_offset, sizeof(struct segment_command_64));

if (is_swap) {

swap_segment_command_64(segment, 0);

}

printf("segname: %s\n", segment->segname);

free(segment);

} else if (cmd->cmd == LC_SEGMENT) {

struct segment_command *segment = load_bytes(obj_file, actual_offset, sizeof(struct segment_command));

if (is_swap) {

swap_segment_command(segment, 0);

}

printf("segname: %s\n", segment->segname);

free(segment);

}

actual_offset += cmd->cmdsize;

free(cmd);

}

}This function doesn’t need is_64 parameter, because we can infer it from cmd type itself (LC_SEGMENT/LC_SEGMENT_64). If it’s not a segment, then we just skip the command and move forward to the next one.

The last thing I want to show is how to retrieve the name of a processor based on a cputype from mach_header. I believe this is not the best option, but it’s acceptable for this artificial example:

struct _cpu_type_names {

cpu_type_t cputype;

const char *cpu_name;

};

static struct _cpu_type_names cpu_type_names[] = {

{ CPU_TYPE_I386, "i386" },

{ CPU_TYPE_X86_64, "x86_64" },

{ CPU_TYPE_ARM, "arm" },

{ CPU_TYPE_ARM64, "arm64" }

};

static const char *cpu_type_name(cpu_type_t cpu_type) {

static int cpu_type_names_size = sizeof(cpu_type_names) / sizeof(struct _cpu_type_names);

for (int i = 0; i < cpu_type_names_size; i++ ) {

if (cpu_type == cpu_type_names[i].cputype) {

return cpu_type_names[i].cpu_name;

}

}

return "unknown";

}OS X provides CPU_TYPE_* for a lot of CPUs, so we can ‘easily’ associate particular magic number with a string literal. To print name of a CPU we need to modify dump_mach_header a bit:

int header_size = sizeof(struct mach_header_64);

struct mach_header_64 *header = load_bytes(obj_file, offset, header_size);

if (is_swap) {

swap_mach_header_64(header, 0);

}

ncmds = header->ncmds;

load_commands_offset += header_size;

printf("%s\n", cpu_type_name(header->cputype)); // <-

free(header);The article is already way too big, so I’m not going to describe how to handle Fat objects, but you can find implementation here: segment_dumper

main 函数是 iOS 程序的入口,我们写的代码都是在 main 函数之后执行的,但是在夜深人静的时候,我的脑海中经常会冒出这样的问题:main 函数之前到底发生了什么?用户点击程序图标之后,我们的 App 是怎样被启动的?这期间系统做了哪些事情、经历了哪些步骤才一步步地调用到程序 main 函数的?于是我又献祭了自己的空闲时间对 iOS 应用的启动流程进行了一番探究。

咳咳,这里先把结论贴出来,然后再一步步分析,对总体流程有了一个大体的认识才不会在技术细节中迷路:

(1) 系统为程序启动做好准备

(2) 系统将控制权交给 Dyld,Dyld 会负责后续的工作

(3) Dyld 加载程序�所需的动态库

(3) Dyld 对程序进行 rebase 以及 bind 操作

(4) Objc SetUp

(5) 运行初始化函数

(6) 执行程序的 main 函数

步骤比较多,不过不用担心,我会结合代码对其进行进一步的讲解。

在用户点击应用后,系统内核会去创建一个新的进程并为应用的执行做好准备,详情可参考趣探 Mach-O:加载过程,之后会去调用 Dyld 来接管后续的工作。Dyld 是 iOS 系统的动态链接器,它的代码在这里,整体来说它的机制还是比较复杂的,所里这里只是简单概括一下,感兴趣的同志可以下载源码阅读。

Dyld 的启动代码源于 dyldStartup.s 文件,在一大串的汇编代码中有个名为 __dyld_start 的方法,它会去调用 dyldbootstrap::start() 方法,然后进一步调用 dyld::_main() 方法,里面包含 App 的整个启动流程,该函数最终返回应用程序 main 函数的地址,最后 Dyld 会去调用它。dyld::_main() 函数的源码很长,所以这里只保留关键信息,并用伪代码进行简化从而得到整体流程:

uintptr_t _main(···/省略参数/···) {

// 1. 设置运行环境

......

// 2. instantiate ImageLoader for main executable

sMainExecutable = instantiateFromLoadedImage(mainExecutableMH, mainExecutableSlide, sExecPath);

......

//3. link main executable

link(sMainExecutable, sEnv.DYLD_BIND_AT_LAUNCH, true, ImageLoader::RPathChain(NULL, NULL), -1);

......

//4. run all initializers

initializeMainExecutable();

......

//5. find entry point for main executable

result = (uintptr_t)sMainExecutable->getThreadPC();

......

return result;

}

接下来我会对以上关键代码进行解读,希望大家对启动流程有着更为清晰的认识。

二进制文件常被称为 image,包括可执行文件、动态库等,ImageLoader 的作用就是将二进制文件加载进内存。dyld::_main() 方法在设置好运行环境后,会调用 instantiateFromLoadedImage 函数将可执行文件加载进内存中,加载过程分为三步:

- 合法性检查。主要是检查可执行文件是否合法,是否能在当前的 CPU 架构下运行。

- 选择 ImageLoader 加载可执行文件。系统会去判断可执行文件的类型,选择相应的 ImageLoader 将其加载进内存空间中。

- 注册 image 信息。可执行文件加载完成后,系统会调用 addImage 函数将其管理起来,并更新内存分布信息。

以上三步完成后,Dyld 会调用 link 函数开始之后的处理流程。另外补充下,如果有同学对 ImageLoader 感兴趣的话,dyld 加载 Mach-O这篇文章是不错的,推荐大家看。

link(sMainExecutable, ......) 函数究竟做了些什么,我们可以从源码中一探究竟:

void ImageLoader::link(···/省略参数/···) {

//dyld::log("ImageLoader::link(%s) refCount=%d, neverUnload=%d\n", imagePath, fDlopenReferenceCount, fNeverUnload);

// clear error strings

(*context.setErrorStrings)(0, NULL, NULL, NULL);

uint64_t t0 = mach_absolute_time();

this->recursiveLoadLibraries(context, preflightOnly, loaderRPaths, imagePath);

context.notifyBatch(dyld_image_state_dependents_mapped, preflightOnly);

// we only do the loading step for preflights

if ( preflightOnly )

return;

uint64_t t1 = mach_absolute_time();

context.clearAllDepths();

this->recursiveUpdateDepth(context.imageCount());

uint64_t t2 = mach_absolute_time();

this->recursiveRebase(context);

context.notifyBatch(dyld_image_state_rebased, false);

uint64_t t3 = mach_absolute_time();

this->recursiveBind(context, forceLazysBound, neverUnload);

uint64_t t4 = mach_absolute_time();

if ( !context.linkingMainExecutable )

this->weakBind(context);

uint64_t t5 = mach_absolute_time();

context.notifyBatch(dyld_image_state_bound, false);

uint64_t t6 = mach_absolute_time();

std::vector<DOFInfo> dofs;

this->recursiveGetDOFSections(context, dofs);

context.registerDOFs(dofs);

uint64_t t7 = mach_absolute_time();

// interpose any dynamically loaded images

if ( !context.linkingMainExecutable && (fgInterposingTuples.size() != 0) ) {

this->recursiveApplyInterposing(context);

}

// clear error strings

(*context.setErrorStrings)(0, NULL, NULL, NULL);

fgTotalLoadLibrariesTime += t1 - t0;

fgTotalRebaseTime += t3 - t2;

fgTotalBindTime += t4 - t3;

fgTotalWeakBindTime += t5 - t4;

fgTotalDOF += t7 - t6;

// done with initial dylib loads

fgNextPIEDylibAddress = 0;

}

link 函数不是很长,这里就全部贴出来了,它首先调用 recursiveLoadLibraries,递归加载程序所需的动态链接库。使用 otool -L 二进制文件路径 可以列出程序的动态链接库:

$ otool -L gaoda

/System/Library/Frameworks/Foundation.framework/Foundation (compatibility version 300.0.0, current version 1349.55.0)

/usr/lib/libobjc.A.dylib (compatibility version 1.0.0, current version 228.0.0)

/usr/lib/libSystem.B.dylib (compatibility version 1.0.0, current version 1238.50.2)

/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreFoundation.framework/CoreFoundation (compatibility version 150.0.0, current version 1349.56.0)

/System/Library/Frameworks/UIKit.framework/UIKit

UIKit 和 Foundation 框架相信大家已经很熟悉了,那么 libobjc.A.dylib 以及 libSystem.B.dylib 是什么呢?libobjc.A.dylib 包含 runtime,而 libSystem.B.dylib 则包含像 libdispatch、libsystem_c 等系统级别的库,二者都是被默认添加到程序中的。动态链接库的加载也是借助 ImageLoader 完成的,但是由于动态链接库本身还可能依赖其他动态链接库,所以整个加载过程是递归进行的。当程序的动态链接库加载完毕后,link 函数进入下一流程。

因为地址空间加载随机化(ASLR,Address Space Layout Randomization)的缘故,二进制文件最终的加载地址与预期地址之间会存在偏移,所以需要进行 rebase 操作,对那些指向文件内部符号的指针进行修正,在 link 函数中该项操作由 recursiveRebase 函数执行。rebase 完成之后,就会进行 bind 操作,修正那些指向其他二进制文件所包含的符号的指针,由 recursiveBind 函数执行。

当 rebase 以及 bind 结束时,link 函数就完成了它的使命,iOS 应用的启动流程也进入到下一阶段,即 Objc SetUp。

Objc Setup 算是 iOS 系统独有的流程了,在 runtime 的初始化函数 _objc_init 中,有这样的代码:

void _objc_init(void) {

......

// Register for unmap first, in case some +load unmaps something

_dyld_register_func_for_remove_image(&unmap_image);

dyld_register_image_state_change_handler(dyld_image_state_bound,

1/*batch*/, &map_2_images);

dyld_register_image_state_change_handler(dyld_image_state_dependents_initialized, 0/*not batch*/, &load_images);

}

Dyld 在 bind 操作结束之后,会发出 dyld_image_state_bound 通知,然后与之绑定的回调函数 map_2_images 就会被调用,它主要做以下几件事来完成 Objc Setup:

- 读取二进制文件的 DATA 段内容,找到与 objc 相关的信息

- 注册 Objc 类

- 确保 selector 的唯一性

- 读取 protocol 以及 category 的信息

除了 map_2_images,我们注意到 _objc_init 还注册了 load_images 函数,它的作用就是调用 Objc 的 + load 方法,它监听 dyld_image_state_dependents_initialized 通知。

虽然我说的很简单,但是在读源码的时候,我发现这部分内容其实是十分复杂而又十分有趣的,鉴于本文主旨是讲启动流程,所以这一块内容先放下,以后有时间了再讲。

Objc SetUp 结束后,Dyld 便开始运行程序的初始化函数,该任务由 initializeMainExecutable 函数执行。整个初始化过程是一个递归的过程,顺序是先将依赖的动态库初始化,然后在对自己初始化。初始化需要做的事情包括:

- 调用 Objc 类的 + load 函数

- 调用 C++ 中带有 constructor 标记的函数

- 非基本类型的 C++ 静态全局变量的创建

当初始化结束之后,可执行文件才处于可用状态,之后 Dyld 就会去调用可执行文件的 main 函数,开始程序的运行。