Solidum is an open, ditributed computing platform that lets anyone build and use decentralized applications that run on blockchain technology.

An introductory paper to Solidum, introduced before launch, which is maintained.

Contents

- Solidum Network

- Philosophy

- Solidum Accounts

- Messages and Transactions

- Code execution

- Blockchain and Mining

- Token Systems

- Identity and Reputation Systems

- Decentralized File Storage

- Decentralized Autonomous Organizations

- Further Applications

- Modified GHOST Implementation

- Computation And Turing-Completeness

- Currency and Issuance

- Hashing Algorithm

- Scalability

- Conclusion

- Further Reading

The design behind Solidum is intended to follow the following principles:

- Simplicity: the Solidum protocol should be as simple as possible, even at the cost of some data storage or time inefficiency. An average programmer should ideally be able to follow and implement the entire specification, so as to fully realize the unprecedented democratizing potential that cryptocurrency brings and further the vision of Solidum as a protocol that is open to all. Any optimization which adds complexity should not be included unless that optimization provides very substantial benefit.

- Universality: a fundamental part of Solidum's design philosophy is that Solidum does not have "features". Instead, Solidum provides an internal Turing-complete scripting language, which a programmer can use to construct any smart contract or transaction type that can be mathematically defined. Want to invent your own financial derivative? With Solidum, you can. Want to make your own currency? Set it up as an Solidum contract. Want to set up a full-scale Daemon or Skynet? You may need to have a few thousand interlocking contracts, and be sure to feed them generously, to do that, but nothing is stopping you with Solidum at your fingertips.

- Modularity: the parts of the Solidum protocol should be designed to be as modular and separable as possible. Over the course of development, our goal is to create a program where if one was to make a small protocol modification in one place, the application stack would continue to function without any further modification. Innovations such as ProgPoW, modified Patricia trees and RLP should be, and are, implemented as separate, feature-complete libraries. This is so that even though they are used in Solidum, even if Solidum does not require certain features, such features are still usable in other protocols as well. Solidum development should be maximally done so as to benefit the entire cryptocurrency ecosystem, not just itself.

- Agility: details of the Solidum protocol are not set in stone. Although we will be extremely judicious about making modifications to high-level constructs, for instance with the sharding roadmap, abstracting execution, with only data availability enshrined in consensus. Computational tests later on in the development process may lead us to discover that certain modifications, e.g. to the protocol architecture or to the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), will substantially improve scalability or security. If any such opportunities are found, we will exploit them.

- Non-discrimination and non-censorship: the protocol should not attempt to actively restrict or prevent specific categories of usage. All regulatory mechanisms in the protocol should be designed to directly regulate the harm and not attempt to oppose specific undesirable applications. A programmer can even run an infinite loop script on top of Ethereum for as long as they are willing to keep paying the per-computational-step transaction fee.

In Solidum, the state is made up of objects called "accounts", with each account having a 20-byte address and state transitions being direct transfers of value and information between accounts. A Solidum account contains four fields:

- The nonce, a counter used to make sure each transaction can only be processed once

- The account's current ether balance

- The account's contract code, if present

- The account's storage (empty by default)

"Ether" or "Solidum" (SUM) is the main internal crypto-fuel of Solidum, and is used to pay transaction fees. In general, there are two types of accounts: externally owned accounts, controlled by private keys, and contract accounts, controlled by their contract code. An externally owned account has no code, and one can send messages from an externally owned account by creating and signing a transaction; in a contract account, every time the contract account receives a message its code activates, allowing it to read and write to internal storage and send other messages or create contracts in turn.

Note that "contracts" in Solidum should not be seen as something that should be "fulfilled" or "complied with"; rather, they are more like "autonomous agents" that live inside of the Solidum execution environment, always executing a specific piece of code when "poked" by a message or transaction, and having direct control over their own ether balance and their own key/value store to keep track of persistent variables.

The term "transaction" is used in Solidum to refer to the signed data package that stores a message to be sent from an externally owned account. Transactions contain:

- The recipient of the message

- A signature identifying the sender

- The amount of ether to transfer from the sender to the recipient

- An optional data field

- A

STARTGASvalue, representing the maximum number of computational steps the transaction execution is allowed to take - A

GASPRICEvalue, representing the fee the sender pays per computational step

The first three are standard fields expected in any cryptocurrency. The data field has no function by default, but the virtual machine has an opcode which a contract can use to access the data; as an example use case, if a contract is functioning as an on-blockchain domain registration service, then it may wish to interpret the data being passed to it as containing two "fields", the first field being a domain to register and the second field being the IP address to register it to. The contract would read these values from the message data and appropriately place them in storage.

The STARTGAS and GASPRICE fields are crucial for Solidum's anti-denial of service model. In order to prevent accidental or hostile infinite loops or other computational wastage in code, each transaction is required to set a limit to how many computational steps of code execution it can use. The fundamental unit of computation is "gas"; usually, a computational step costs 1 gas, but some operations cost higher amounts of gas because they are more computationally expensive, or increase the amount of data that must be stored as part of the state. There is also a fee of 5 gas for every byte in the transaction data. The intent of the fee system is to require an attacker to pay proportionately for every resource that they consume, including computation, bandwidth and storage; hence, any transaction that leads to the network consuming a greater amount of any of these resources must have a gas fee roughly proportional to the increment.

The code in Solidum contracts is written in a low-level, stack-based bytecode language, referred to as "Ethereum virtual machine code" or "EVM code". The code consists of a series of bytes, where each byte represents an operation. In general, code execution is an infinite loop that consists of repeatedly carrying out the operation at the current program counter (which begins at zero) and then incrementing the program counter by one, until the end of the code is reached or an error or STOP or RETURN instruction is detected. The operations have access to three types of space in which to store data:

- The stack, a last-in-first-out container to which values can be pushed and popped

- Memory, an infinitely expandable byte array

- The contract's long-term storage, a key/value store. Unlike stack and memory, which reset after computation ends, storage persists for the long term.

The code can also access the value, sender and data of the incoming message, as well as block header data, and the code can also return a byte array of data as an output.

The formal execution model of EVM code is surprisingly simple. While the Ethereum virtual machine is running, its full computational state can be defined by the tuple (block_state, transaction, message, code, memory, stack, pc, gas), where block_state is the global state containing all accounts and includes balances and storage. At the start of every round of execution, the current instruction is found by taking the pc-th byte of code (or 0 if pc >= len(code)), and each instruction has its own definition in terms of how it affects the tuple. For example, ADD pops two items off the stack and pushes their sum, reduces gas by 1 and increments pc by 1, and SSTORE pops the top two items off the stack and inserts the second item into the contract's storage at the index specified by the first item. Although there are many ways to optimize Ethereum virtual machine execution via just-in-time compilation, a basic implementation of Ethereum can be done in a few hundred lines of code.

The Solidum blockchain is in many ways similar to the Bitcoin blockchain, although it does have some differences. The main difference between Solidum and Bitcoin with regard to the blockchain architecture is that, unlike Bitcoin(which only contains a copy of the transaction list), Solidum blocks contain a copy of both the transaction list and the most recent state. Aside from that, two other values, the block number and the difficulty, are also stored in the block. The basic block validation algorithm in Solidum is as follows:

- Check if the previous block referenced exists and is valid.

- Check that the timestamp of the block is greater than that of the referenced previous block and less than 15 minutes into the future

- Check that the block number, difficulty, transaction root, uncle root and gas limit (various low-level Ethereum-specific concepts) are valid.

- Check that the proof of work on the block is valid.

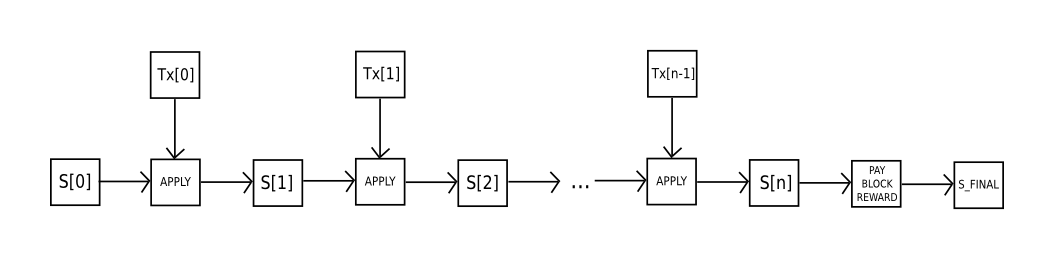

- Let

S[0]be the state at the end of the previous block. - Let

TXbe the block's transaction list, withntransactions. For alliin0...n-1, setS[i+1] = APPLY(S[i],TX[i]). If any application returns an error, or if the total gas consumed in the block up until this point exceeds theGASLIMIT, return an error. - Let

S_FINALbeS[n], but adding the block reward paid to the miner. - Check if the Merkle tree root of the state

S_FINALis equal to the final state root provided in the block header. If it is, the block is valid; otherwise, it is not valid.

The approach may seem highly inefficient at first glance, because it needs to store the entire state with each block, but in reality efficiency should be comparable to that of Bitcoin. The reason is that the state is stored in the tree structure, and after every block only a small part of the tree needs to be changed. Thus, in general, between two adjacent blocks the vast majority of the tree should be the same, and therefore the data can be stored once and referenced twice using pointers (ie. hashes of subtrees). A special kind of tree known as a "Patricia tree" is used to accomplish this, including a modification to the Merkle tree concept that allows for nodes to be inserted and deleted, and not just changed, efficiently. Additionally, because all of the state information is part of the last block, there is no need to store the entire blockchain history - a strategy which, if it could be applied to Bitcoin, can be calculated to provide 5-20x savings in space.

A commonly asked question is "where" contract code is executed, in terms of physical hardware. This has a simple answer: the process of executing contract code is part of the definition of the state transition function, which is part of the block validation algorithm, so if a transaction is added into block B the code execution spawned by that transaction will be executed by all nodes, now and in the future, that download and validate block B.

On-blockchain token systems have many applications ranging from sub-currencies representing assets such as USD or gold to company stocks, individual tokens representing smart property, secure unforgeable coupons, and even token systems with no ties to conventional value at all, used as point systems for incentivization. Token systems are surprisingly easy to implement in Ethereum. The key point to understand is that a currency, or token system, fundamentally is a database with one operation: subtract X units from A and give X units to B, with the provision that (1) A had at least X units before the transaction and (2) the transaction is approved by A. All that it takes to implement a token system is to implement this logic into a contract.

The basic code for implementing a token system in Serpent looks as follows:

def send(to, value):

if self.storage[msg.sender] >= value:

self.storage[msg.sender] = self.storage[msg.sender] - value

self.storage[to] = self.storage[to] + value

This is essentially a literal implementation of the "banking system" state transition function described further above in this document. A few extra lines of code need to be added to provide for the initial step of distributing the currency units in the first place and a few other edge cases, and ideally a function would be added to let other contracts query for the balance of an address. But that's all there is to it. Theoretically, Ethereum-based token systems acting as sub-currencies can potentially include another important feature that on-chain Bitcoin-based meta-currencies lack: the ability to pay transaction fees directly in that currency. The way this would be implemented is that the contract would maintain an ether balance with which it would refund ether used to pay fees to the sender, and it would refill this balance by collecting the internal currency units that it takes in fees and reselling them in a constant running auction. Users would thus need to "activate" their accounts with ether, but once the ether is there it would be reusable because the contract would refund it each time.

The earliest alternative cryptocurrency of all, Namecoin, attempted to use a Bitcoin-like blockchain to provide a name registration system, where users can register their names in a public database alongside other data. The major cited use case is for a DNS system, mapping domain names like "bitcoin.org" (or, in Namecoin's case, "bitcoin.bit") to an IP address. Other use cases include email authentication and potentially more advanced reputation systems. Here is the basic contract to provide a Namecoin-like name registration system on Solidum:

def register(name, value):

if !self.storage[name]:

self.storage[name] = value

The contract is very simple; all it is a database inside the Ethereum network that can be added to, but not modified or removed from. Anyone can register a name with some value, and that registration then sticks forever. A more sophisticated name registration contract will also have a "function clause" allowing other contracts to query it, as well as a mechanism for the "owner" (ie. the first registerer) of a name to change the data or transfer ownership. One can even add reputation and web-of-trust functionality on top.

Over the past few years, there have emerged a number of popular online file storage startups, the most prominent being Dropbox, seeking to allow users to upload a backup of their hard drive and have the service store the backup and allow the user to access it in exchange for a monthly fee. However, at this point the file storage market is at times relatively inefficient; a cursory look at various existing solutions shows that, particularly at the "uncanny valley" 20-200 GB level at which neither free quotas nor enterprise-level discounts kick in, monthly prices for mainstream file storage costs are such that you are paying for more than the cost of the entire hard drive in a single month. Solidum contracts can allow for the development of a decentralized file storage ecosystem, where individual users can earn small quantities of money by renting out their own hard drives and unused space can be used to further drive down the costs of file storage.

The key underpinning piece of such a device would be what we have termed the "decentralized Dropbox contract". This contract works as follows. First, one splits the desired data up into blocks, encrypting each block for privacy, and builds a Merkle tree out of it. One then makes a contract with the rule that, every N blocks, the contract would pick a random index in the Merkle tree (using the previous block hash, accessible from contract code, as a source of randomness), and give X ether to the first entity to supply a transaction with a simplified payment verification-like proof of ownership of the block at that particular index in the tree. When a user wants to re-download their file, they can use a micropayment channel protocol (eg. pay 1 szabo per 32 kilobytes) to recover the file; the most fee-efficient approach is for the payer not to publish the transaction until the end, instead replacing the transaction with a slightly more lucrative one with the same nonce after every 32 kilobytes.

An important feature of the protocol is that, although it may seem like one is trusting many random nodes not to decide to forget the file, one can reduce that risk down to near-zero by splitting the file into many pieces via secret sharing, and watching the contracts to see each piece is still in some node's possession. If a contract is still paying out money, that provides a cryptographic proof that someone out there is still storing the file.

The general concept of a "decentralized autonomous organization" is that of a virtual entity that has a certain set of members or shareholders which, perhaps with a 67% majority, have the right to spend the entity's funds and modify its code. The members would collectively decide on how the organization should allocate its funds. Methods for allocating a DAO's funds could range from bounties, salaries to even more exotic mechanisms such as an internal currency to reward work. This essentially replicates the legal trappings of a traditional company or nonprofit but using only cryptographic blockchain technology for enforcement. So far much of the talk around DAOs has been around the "capitalist" model of a "decentralized autonomous corporation" (DAC) with dividend-receiving shareholders and tradable shares; an alternative, perhaps described as a "decentralized autonomous community", would have all members have an equal share in the decision making and require 67% of existing members to agree to add or remove a member. The requirement that one person can only have one membership would then need to be enforced collectively by the group.

A general outline for how to code a DAO is as follows. The simplest design is simply a piece of self-modifying code that changes if two thirds of members agree on a change. Although code is theoretically immutable, one can easily get around this and have de-facto mutability by having chunks of the code in separate contracts, and having the address of which contracts to call stored in the modifiable storage. In a simple implementation of such a DAO contract, there would be three transaction types, distinguished by the data provided in the transaction:

[0,i,K,V]to register a proposal with indexito change the address at storage indexKto valueV[1,i]to register a vote in favor of proposali[2,i]to finalize proposaliif enough votes have been made

The contract would then have clauses for each of these. It would maintain a record of all open storage changes, along with a list of who voted for them. It would also have a list of all members. When any storage change gets to two thirds of members voting for it, a finalizing transaction could execute the change. A more sophisticated skeleton would also have built-in voting ability for features like sending a transaction, adding members and removing members, and may even provide for Liquid Democracy-style vote delegation (ie. anyone can assign someone to vote for them, and assignment is transitive so if A assigns B and B assigns C then C determines A's vote). This design would allow the DAO to grow organically as a decentralized community, allowing people to eventually delegate the task of filtering out who is a member to specialists, although unlike in the "current system" specialists can easily pop in and out of existence over time as individual community members change their alignments.

An alternative model is for a decentralized corporation, where any account can have zero or more shares, and two thirds of the shares are required to make a decision. A complete skeleton would involve asset management functionality, the ability to make an offer to buy or sell shares, and the ability to accept offers (preferably with an order-matching mechanism inside the contract). Delegation would also exist Liquid Democracy-style, generalizing the concept of a "board of directors".

1. Savings wallets. Suppose that Alice wants to keep her funds safe, but is worried that she will lose or someone will hack her private key. She puts ether into a contract with Bob, a bank, as follows:

- Alice alone can withdraw a maximum of 1% of the funds per day.

- Bob alone can withdraw a maximum of 1% of the funds per day, but Alice has the ability to make a transaction with her key shutting off this ability.

- Alice and Bob together can withdraw anything.

Normally, 1% per day is enough for Alice, and if Alice wants to withdraw more she can contact Bob for help. If Alice's key gets hacked, she runs to Bob to move the funds to a new contract. If she loses her key, Bob will get the funds out eventually. If Bob turns out to be malicious, then she can turn off his ability to withdraw.

2. Crop insurance. One can easily make a financial derivatives contract but using a data feed of the weather instead of any price index. If a farmer in Iowa purchases a derivative that pays out inversely based on the precipitation in Iowa, then if there is a drought, the farmer will automatically receive money and if there is enough rain the farmer will be happy because their crops would do well. This can be expanded to natural disaster insurance generally.

3. A decentralized data feed. For financial contracts for difference, it may actually be possible to decentralize the data feed via a protocol called SchellingCoin. SchellingCoin basically works as follows: N parties all put into the system the value of a given datum (eg. the SUM/USD price), the values are sorted, and everyone between the 25th and 75th percentile gets one token as a reward. Everyone has the incentive to provide the answer that everyone else will provide, and the only value that a large number of players can realistically agree on is the obvious default: the truth. This creates a decentralized protocol that can theoretically provide any number of values, including the SUM/USD price, the temperature in Berlin or even the result of a particular hard computation.

4. Smart multisignature escrow. Bitcoin allows multisignature transaction contracts where, for example, three out of a given five keys can spend the funds. Solidum allows for more granularity; for example, four out of five can spend everything, three out of five can spend up to 10% per day, and two out of five can spend up to 0.5% per day. Additionally, Solidum multisig is asynchronous - two parties can register their signatures on the blockchain at different times and the last signature will automatically send the transaction.

5. Cloud computing. The EVM technology can also be used to create a verifiable computing environment, allowing users to ask others to carry out computations and then optionally ask for proofs that computations at certain randomly selected checkpoints were done correctly. This allows for the creation of a cloud computing market where any user can participate with their desktop, laptop or specialized server, and spot-checking together with security deposits can be used to ensure that the system is trustworthy (ie. nodes cannot profitably cheat). Although such a system may not be suitable for all tasks; tasks that require a high level of inter-process communication, for example, cannot easily be done on a large cloud of nodes. Other tasks, however, are much easier to parallelize; projects like SETI@home, folding@home and genetic algorithms can easily be implemented on top of such a platform.

6. Peer-to-peer gambling. Any number of peer-to-peer gambling protocols, such as Frank Stajano and Richard Clayton's Cyberdice, can be implemented on the Solidum blockchain. The simplest gambling protocol is actually simply a contract for difference on the next block hash, and more advanced protocols can be built up from there, creating gambling services with near-zero fees that have no ability to cheat.

7. Prediction markets. Provided an oracle or SchellingCoin, prediction markets are also easy to implement, and prediction markets together with SchellingCoin may prove to be the first mainstream application of futarchy as a governance protocol for decentralized organizations.

8. On-chain decentralized marketplaces, using the identity and reputation system as a base.

The "Greedy Heaviest Observed Subtree" (GHOST) protocol is an innovation first introduced by Yonatan Sompolinsky and Aviv Zohar in December 2013. The motivation behind GHOST is that blockchains with fast confirmation times currently suffer from reduced security due to a high stale rate - because blocks take a certain time to propagate through the network, if miner A mines a block and then miner B happens to mine another block before miner A's block propagates to B, miner B's block will end up wasted and will not contribute to network security. Furthermore, there is a centralization issue: if miner A is a mining pool with 30% hashpower and B has 10% hashpower, A will have a risk of producing a stale block 70% of the time (since the other 30% of the time A produced the last block and so will get mining data immediately) whereas B will have a risk of producing a stale block 90% of the time. Thus, if the block interval is short enough for the stale rate to be high, A will be substantially more efficient simply by virtue of its size. With these two effects combined, blockchains which produce blocks quickly are very likely to lead to one mining pool having a large enough percentage of the network hashpower to have de facto control over the mining process.

As described by Sompolinsky and Zohar, GHOST solves the first issue of network security loss by including stale blocks in the calculation of which chain is the "longest"; that is to say, not just the parent and further ancestors of a block, but also the stale descendants of the block's ancestor (in Ethereum jargon, "uncles") are added to the calculation of which block has the largest total proof of work backing it. To solve the second issue of centralization bias, we go beyond the protocol described by Sompolinsky and Zohar, and also provide block rewards to stales: a stale block receives 87.5% of its base reward, and the nephew that includes the stale block receives the remaining 12.5%. Transaction fees, however, are not awarded to uncles.

Solidum implements a simplified version of GHOST which only goes down seven levels. Specifically, it is defined as follows:

- A block must specify a parent, and it must specify 0 or more uncles

- An uncle included in block

Bmust have the following properties:- It must be a direct child of the

k-th generation ancestor ofB, where2 <= k <= 7. - It cannot be an ancestor of

B - An uncle must be a valid block header, but does not need to be a previously verified or even valid block

- An uncle must be different from all uncles included in previous blocks and all other uncles included in the same block (non-double-inclusion)

- It must be a direct child of the

- For every uncle

Uin blockB, the miner ofBgets an additional 3.125% added to its coinbase reward and the miner of U gets 93.75% of a standard coinbase reward.

This limited version of GHOST, with uncles includable only up to 7 generations, was used for two reasons. First, unlimited GHOST would include too many complications into the calculation of which uncles for a given block are valid. Second, unlimited GHOST with compensation as used in Solidum removes the incentive for a miner to mine on the main chain and not the chain of a public attacker.

Because every transaction published into the blockchain imposes on the network the cost of needing to download and verify it, there is a need for some regulatory mechanism, typically involving transaction fees, to prevent abuse. The default approach, used in Bitcoin, is to have purely voluntary fees, relying on miners to act as the gatekeepers and set dynamic minimums. This approach has been received very favorably in the Bitcoin community particularly because it is "market-based", allowing supply and demand between miners and transaction senders determine the price. The problem with this line of reasoning is, however, that transaction processing is not a market; although it is intuitively attractive to construe transaction processing as a service that the miner is offering to the sender, in reality every transaction that a miner includes will need to be processed by every node in the network, so the vast majority of the cost of transaction processing is borne by third parties and not the miner that is making the decision of whether or not to include it. Hence, tragedy-of-the-commons problems are very likely to occur.

However, as it turns out this flaw in the market-based mechanism, when given a particular inaccurate simplifying assumption, magically cancels itself out. The argument is as follows. Suppose that:

- A transaction leads to

koperations, offering the rewardkRto any miner that includes it whereRis set by the sender andkandRare (roughly) visible to the miner beforehand. - An operation has a processing cost of

Cto any node (ie. all nodes have equal efficiency) - There are

Nmining nodes, each with exactly equal processing power (ie.1/Nof total) - No non-mining full nodes exist.

A miner would be willing to process a transaction if the expected reward is greater than the cost. Thus, the expected reward is kR/N since the miner has a 1/N chance of processing the next block, and the processing cost for the miner is simply kC. Hence, miners will include transactions where kR/N > kC, or R > NC. Note that R is the per-operation fee provided by the sender, and is thus a lower bound on the benefit that the sender derives from the transaction, and NC is the cost to the entire network together of processing an operation. Hence, miners have the incentive to include only those transactions for which the total utilitarian benefit exceeds the cost.

However, there are several important deviations from those assumptions in reality:

- The miner does pay a higher cost to process the transaction than the other verifying nodes, since the extra verification time delays block propagation and thus increases the chance the block will become a stale.

- There do exist non-mining full nodes.

- The mining power distribution may end up radically inegalitarian in practice.

- Speculators, political enemies and crazies whose utility function includes causing harm to the network do exist, and they can cleverly set up contracts where their cost is much lower than the cost paid by other verifying nodes.

(1) provides a tendency for the miner to include fewer transactions, and (2) increases NC; hence, these two effects at least partially cancel each other out.How? (3) and (4) are the major issue; to solve them we simply institute a floating cap: no block can have more operations than BLK_LIMIT_FACTOR times the long-term exponential moving average. Specifically:

blk.oplimit = floor((blk.parent.oplimit * (EMAFACTOR - 1) + floor(parent.opcount * BLK_LIMIT_FACTOR)) / EMA_FACTOR)

BLK_LIMIT_FACTOR and EMA_FACTOR are constants that will be set to 65536 and 1.5 for the time being, but will likely be changed after further analysis.

There is another factor disincentivizing large block sizes in Bitcoin: blocks that are large will take longer to propagate, and thus have a higher probability of becoming stales. In Solidum, highly gas-consuming blocks can also take longer to propagate both because they are physically larger and because they take longer to process the transaction state transitions to validate. This delay disincentive is a significant consideration in Bitcoin, but less so in Solidum because of the GHOST protocol; hence, relying on regulated block limits provides a more stable baseline.

An important note is that the Ethereum virtual machine is Turing-complete; this means that EVM code can encode any computation that can be conceivably carried out, including infinite loops. EVM code allows looping in two ways. First, there is a JUMP instruction that allows the program to jump back to a previous spot in the code, and a JUMPI instruction to do conditional jumping, allowing for statements like while x < 27: x = x * 2. Second, contracts can call other contracts, potentially allowing for looping through recursion. This naturally leads to a problem: can malicious users essentially shut miners and full nodes down by forcing them to enter into an infinite loop? The issue arises because of a problem in computer science known as the halting problem: there is no way to tell, in the general case, whether or not a given program will ever halt.

As described in the state transition section, our solution works by requiring a transaction to set a maximum number of computational steps that it is allowed to take, and if execution takes longer computation is reverted but fees are still paid. Messages work in the same way. To show the motivation behind our solution, consider the following examples:

- An attacker creates a contract which runs an infinite loop, and then sends a transaction activating that loop to the miner. The miner will process the transaction, running the infinite loop, and wait for it to run out of gas. Even though the execution runs out of gas and stops halfway through, the transaction is still valid and the miner still claims the fee from the attacker for each computational step.

- An attacker creates a very long infinite loop with the intent of forcing the miner to keep computing for such a long time that by the time computation finishes a few more blocks will have come out and it will not be possible for the miner to include the transaction to claim the fee. However, the attacker will be required to submit a value for

STARTGASlimiting the number of computational steps that execution can take, so the miner will know ahead of time that the computation will take an excessively large number of steps. - An attacker sees a contract with code of some form like

send(A,contract.storage[A]); contract.storage[A] = 0, and sends a transaction with just enough gas to run the first step but not the second (ie. making a withdrawal but not letting the balance go down). The contract author does not need to worry about protecting against such attacks, because if execution stops halfway through the changes they get reverted. - A financial contract works by taking the median of nine proprietary data feeds in order to minimize risk. An attacker takes over one of the data feeds, which is designed to be modifiable via the variable-address-call mechanism described in the section on DAOs, and converts it to run an infinite loop, thereby attempting to force any attempts to claim funds from the financial contract to run out of gas. However, the financial contract can set a gas limit on the message to prevent this problem.

The alternative to Turing-completeness is Turing-incompleteness, where JUMP and JUMPI do not exist and only one copy of each contract is allowed to exist in the call stack at any given time. With this system, the fee system described and the uncertainties around the effectiveness of our solution might not be necessary, as the cost of executing a contract would be bounded above by its size. Additionally, Turing-incompleteness is not even that big a limitation; out of all the contract examples we have conceived internally, so far only one required a loop, and even that loop could be removed by making 26 repetitions of a one-line piece of code. Given the serious implications of Turing-completeness, and the limited benefit, why not simply have a Turing-incomplete language? In reality, however, Turing-incompleteness is far from a neat solution to the problem. To see why, consider the following contracts:

C0: call(C1); call(C1);

C1: call(C2); call(C2);

C2: call(C3); call(C3);

...

C49: call(C50); call(C50);

C50: (run one step of a program and record the change in storage)

Now, send a transaction to A. Thus, in 51 transactions, we have a contract that takes up 250 computational steps. Miners could try to detect such logic bombs ahead of time by maintaining a value alongside each contract specifying the maximum number of computational steps that it can take, and calculating this for contracts calling other contracts recursively, but that would require miners to forbid contracts that create other contracts (since the creation and execution of all 26 contracts above could easily be rolled into a single contract). Another problematic point is that the address field of a message is a variable, so in general it may not even be possible to tell which other contracts a given contract will call ahead of time. Hence, all in all, we have a surprising conclusion: Turing-completeness is surprisingly easy to manage, and the lack of Turing-completeness is equally surprisingly difficult to manage unless the exact same controls are in place - but in that case why not just let the protocol be Turing-complete?

The Solidum network includes its own built-in currency, solidum, which serves the dual purpose of providing a primary liquidity layer to allow for efficient exchange between various types of digital assets and, more importantly, of providing a mechanism for paying transaction fees. For convenience and to avoid future argument (see the current mBTC/uBTC/satoshi debate in Bitcoin), the denominations will be pre-labelled:

- 1: wei

- 1012: szabo

- 1015: finney

- 1018: solidum (sum)

This should be taken as an expanded version of the concept of "dollars" and "cents" or "BTC" and "satoshi". In the near future, we expect "solidum" to be used for ordinary transactions, "finney" for microtransactions and "szabo" and "wei" for technical discussions around fees and protocol implementation; the remaining denominations may become useful later and should not be included in clients at this point.

The issuance model will be as follows:

| Block number | ERA | Miners | SDF | SCF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 5,000,000 | E1 | 160 SUM | 20 SUM | 20 SUM |

| 5,000,000 - 10,000,000 | E2 | 80 SUM | 10 SUM | 10 SUM |

| 10,000,000 - 15,000,000 | E3 | 40 SUM | 5 SUM | 5 SUM |

| 15,000,000 - 20,000,000 | E4 | 20 SUM | 2,5 SUM | 2,5 SUM |

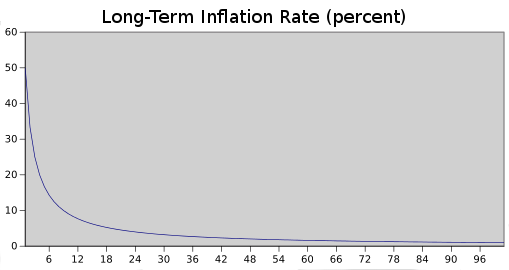

Long-Term Supply Growth Rate (percent)

Despite the linear currency issuance, just like with Bitcoin over time the supply growth rate nevertheless tends to zero

The two main choices in the above model are (1) the existence and size of an endowment pool, and (2) the existence of a permanently growing linear supply, as opposed to a capped supply as in Bitcoin. The justification of the endowment pool is as follows. If the endowment pool did not exist, and the linear issuance reduced to 0.217x to provide the same inflation rate, then the total quantity of ether would be 16.5% less and so each unit would be 19.8% more valuable. Hence, in the equilibrium 19.8% more ether would be purchased in the sale, so each unit would once again be exactly as valuable as before. The organization would also then have 1.198x as much BTC, which can be considered to be split into two slices: the original BTC, and the additional 0.198x. Hence, this situation is exactly equivalent to the endowment, but with one important difference: the organization holds purely BTC, and so is not incentivized to support the value of the ether unit.

The permanent linear supply growth model reduces the risk of what some see as excessive wealth concentration in Bitcoin, and gives individuals living in present and future eras a fair chance to acquire currency units, while at the same time retaining a strong incentive to obtain and hold ether because the "supply growth rate" as a percentage still tends to zero over time. We also theorize that because coins are always lost over time due to carelessness, death, etc, and coin loss can be modeled as a percentage of the total supply per year, that the total currency supply in circulation will in fact eventually stabilize at a value equal to the annual issuance divided by the loss rate (eg. at a loss rate of 1%, once the supply reaches 26X then 0.26X will be mined and 0.26X lost every year, creating an equilibrium).

ProgPoW is a proof-of-work algorithm designed to close the efficency gap available to specialized ASICs. It utilizes almost all parts of commodity hardware (GPUs), and comes pre-tuned for the most common hardware utilized in the Solidum network.

Ever since the first bitcoin mining ASIC was released, many new Proof of Work algorithms have been created with the intention of being “ASIC-resistant”. The goal of “ASIC-resistance” is to resist the centralization of PoW mining power such that these coins couldn’t be so easily manipulated by a few players.

This document presents an overview of the algorithm and examines what it means to be “ASIC-resistant.” Next, we compare existing PoW designs by analyzing how each algorithm executes in hardware. Finally, we present the detailed implementation by walking through the code.

The design goal of ProgPoW is to have the algorithm’s requirements match what is available on commodity GPUs: If the algorithm were to be implemented on a custom ASIC there should be little opportunity for efficiency gains compared to a commodity GPU.

The main elements of the algorithm are:

- Changes keccak_f1600 (with 64-bit words) to keccak_f800 (with 32-bit words) to reduce impact on total power

- Increases mix state.

- Adds a random sequence of math in the main loop.

- Adds reads from a small, low-latency cache that supports random addresses.

- Increases the DRAM read from 128 bytes to 256 bytes.

The random sequence changes every PROGPOW_PERIOD (50 blocks or about 12.5 minutes). When mining source code is generated for the random sequence and compiled on the host CPU. The GPU will execute the compiled code where what math to perform and what mix state to use are already resolved.

While a custom ASIC to implement this algorithm is still possible, the efficiency gains available are minimal. The majority of a commodity GPU is required to support the above elements. The only optimizations available are:

- Remove the graphics pipeline (displays, geometry engines, texturing, etc)

- Remove floating point math

- A few ISA tweaks, like instructions that exactly match the merge() function

These would result in minimal, roughly 1.1-1.2x, efficiency gains. This is much less than the 2x for Ethash or 50x for Cryptonight.

With the growth of large mining pools, the control of hashing power has been delegated to the top few pools to provide a steadier economic return for small miners. While some have made the argument that large centralized pools defeats the purpose of “ASIC resistance,” it’s important to note that ASIC based coins are even more centralized for several reasons.

- No natural distribution: There isn’t an economic purpose for ultra-specialized hardware outside of mining and thus no reason for most people to have it.

- No reserve group: Thus, there’s no reserve pool of hardware or reserve pool of interested parties to jump in when coin price is volatile and attractive for manipulation.

- High barrier to entry: Initial miners are those rich enough to invest capital and ecological resources on the unknown experiment a new coin may be. Thus, initial coin distribution through mining will be very limited causing centralized economic bias.

- Delegated centralization vs implementation centralization: While pool centralization is delegated, hardware monoculture is not: only the limiter buyers of this hardware can participate so there isn’t even the possibility of divesting control on short notice.

- No obvious decentralization of control even with decentralized mining: Once large custom ASIC makers get into the game, designing back-doored hardware is trivial. ASIC makers have no incentive to be transparent or fair in market participation.

While the goal of “ASIC resistance” is valuable, the entire concept of “ASIC resistance” is a bit of a fallacy. CPUs and GPUs are themselves ASICs. Any algorithm that can run on a commodity ASIC (a CPU or GPU) by definition can have a customized ASIC created for it with slightly less functionality. Some algorithms are intentionally made to be “ASIC friendly” - where an ASIC implementation is drastically more efficient than the same algorithm running on general purpose hardware. The protection that this offers when the coin is unknown also makes it an attractive target for a dedicate mining ASIC company as soon as it becomes useful.

Therefore, ASIC resistance is: the efficiency difference of specilized hardware versus hardware that has a wider adoption and applicability. A smaller efficiency difference between custom vs general hardware mean higher resistance and a better algorithm. This efficiency difference is the proper metric to use when comparing the quality of PoW algorithms. Efficiency could mean absolute performance, performance per watt, or performance per dollar - they are all highly correlated. If a single entity creates and controls an ASIC that is drastically more efficient, they can gain 51% of the network hashrate and possibly stage an attack.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 1000X

The SHA algorithm is a sequence of simple math operations - additions, logical ops, and rotates.

To process a single op on a CPU or GPU requires fetching and decoding an instruction, reading data from a register file, executing the instruction, and then writing the result back to a register file. This takes significant time and power.

A single op implemented in an ASIC takes a handful of transistors and wires. This means every individual op takes negligible power, area, or time. A hashing core is built by laying out the sequence of required ops.

The hashing core can execute the required sequence of ops in much less time, and using less power or area, than doing the same sequence on a CPU or GPU. A bitcoin ASIC consists of a number of identical hashing cores and some minimal off-chip communication.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 1000X

Scrypt and NeoScrypt are similar to SHA in the arithmetic and bitwise operations used. Unfortunately, popular coins such as Litecoin only use a scratchpad size between 32kb and 128kb for their PoW mining algorithm. This scratch pad is small enough to trivially fit on an ASIC next to the math core. The implementation of the math core would be very similar to SHA, with similar efficiency gains.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 1000X

X11 (and similar X##) require an ASIC that has 11 unique hashing cores pipelined in a fixed sequence. Each individual hashing core would have similar efficiency to an individual SHA core, so the overall design will have the same efficiency gains.

X16R requires the multiple hashing cores to interact through a simple sequencing state machine. Each individual core will have similar efficiency gains and the sequencing logic will take minimal power, area, or time.

The Baikal BK-X is an existing ASIC with multiple hashing cores and a programmable sequencer. It has been upgraded to enable new algorithms that sequence the hashes in different orders.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 100X

The ~150mb of state is large but possible on an ASIC. The binning, sorting, and comparing of bit strings could be implemented on an ASIC at extremely high speed.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 100X

The amount of state required on-chip is not clear as there are Time/Memory Tradeoff attacks. A specialized graph traversal core would have similar efficiency gains to a SHA compute core.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 50X

Compared to Scrypt, CryptoNight does much less compute and requires a full 2mb of scratch pad (there is no known Time/Memory Tradeoff attack). The large scratch pad will dominate the ASIC implementation and limit the number of hashing cores, limiting the absolute performance of the ASIC. An ASIC will consist almost entirely of just on-die SRAM.

- Potential ASIC efficiency gain ~ 2X

Ethash requires external memory due to the large size of the DAG. However that is all that it requires - there is minimal compute that is done on the result loaded from memory. As a result a custom ASIC could remove most of the complexity, and power, of a GPU and be just a memory interface connected to a small compute engine.

The DAG is generated exactly as in Ethash. All the parameters (ephoch length, DAG size, etc) are unchanged. See the original Ethash spec for details on generating the DAG.

ProgPoW can be tuned using the following parameters. The proposed settings have been tuned for a range of existing, commodity GPUs:

PROGPOW_PERIOD: Number of blocks before changing the random programPROGPOW_LANES: The number of parallel lanes that coordinate to calculate a single hash instancePROGPOW_REGS: The register file usage sizePROGPOW_DAG_LOADS: Number of uint32 loads from the DAG per lanePROGPOW_CACHE_BYTES: The size of the cachePROGPOW_CNT_DAG: The number of DAG accesses, defined as the outer loop of the algorithm (64 is the same as Ethash)PROGPOW_CNT_CACHE: The number of cache accesses per loopPROGPOW_CNT_MATH: The number of math operations per loop

| Parameter | 0.9.2 | 0.9.3 |

|---|---|---|

PROGPOW_PERIOD |

50 |

10 |

PROGPOW_LANES |

16 |

16 |

PROGPOW_REGS |

32 |

32 |

PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS |

4 |

4 |

PROGPOW_CACHE_BYTES |

16x1024 |

16x1024 |

PROGPOW_CNT_DAG |

64 |

64 |

PROGPOW_CNT_CACHE |

12 |

11 |

PROGPOW_CNT_MATH |

20 |

18 |

The random program changes every PROGPOW_PERIOD blocks (default 50, roughly 12.5 minutes) to ensure the hardware executing the algorithm is fully programmable. If the program only changed every DAG epoch (roughly 5 days) certain miners could have time to develop hand-optimized versions of the random sequence, giving them an undue advantage.

Sample code is written in C++, this should be kept in mind when evaluating the code in the specification.

All numerics are computed using unsinged 32 bit integers. Any overflows are trimmed off before proceeding to the next computation. Languages that use numerics not fixed to bit lenghts (such as Python and JavaScript) or that only use signed integers (such as Java) will need to keep their languages' quirks in mind. The extensive use of 32 bit data values aligns with modern GPUs internal data architectures.

ProgPoW uses a 32-bit variant of FNV1a for merging data. The existing Ethash uses a similar vaiant of FNV1 for merging, but FNV1a provides better distribution properties.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

const uint32_t FNV_PRIME = 0x1000193;

const uint32_t FNV_OFFSET_BASIS = 0x811c9dc5;

uint32_t fnv1a(uint32_t h, uint32_t d)

{

return (h ^ d) * FNV_PRIME;

}ProgPow uses KISS99 for random number generation. This is the simplest (fewest instruction) random generator that passes the TestU01 statistical test suite. A more complex random number generator like Mersenne Twister can be efficiently implemented on a specialized ASIC, providing an opportunity for efficiency gains.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

typedef struct {

uint32_t z, w, jsr, jcong;

} kiss99_t;

// KISS99 is simple, fast, and passes the TestU01 suite

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KISS_(algorithm)

// http://www.cse.yorku.ca/~oz/marsaglia-rng.html

uint32_t kiss99(kiss99_t &st)

{

st.z = 36969 * (st.z & 65535) + (st.z >> 16);

st.w = 18000 * (st.w & 65535) + (st.w >> 16);

uint32_t MWC = ((st.z << 16) + st.w);

st.jsr ^= (st.jsr << 17);

st.jsr ^= (st.jsr >> 13);

st.jsr ^= (st.jsr << 5);

st.jcong = 69069 * st.jcong + 1234567;

return ((MWC^st.jcong) + st.jsr);

}The fill_mix function populates an array of int32 values used by each lane in the hash calculations.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

void fill_mix(

uint64_t seed,

uint32_t lane_id,

uint32_t mix[PROGPOW_REGS]

)

{

// Use FNV to expand the per-warp seed to per-lane

// Use KISS to expand the per-lane seed to fill mix

kiss99_t st;

st.z = fnv1a(FNV_OFFSET_BASIS, seed);

st.w = fnv1a(st.z, seed >> 32);

st.jsr = fnv1a(st.w, lane_id);

st.jcong = fnv1a(st.jsr, lane_id);

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_REGS; i++)

mix[i] = kiss99(st);

}Like Ethash Keccak is used to seed the sequence per-nonce and to produce the final result. The keccak-f800 variant is used as the 32-bit word size matches the native word size of modern GPUs. The implementation is a variant of SHAKE with width=800, bitrate=576, capacity=224, output=256, and no padding. The result of keccak is treated as a 256-bit big-endian number - that is result byte 0 is the MSB of the value.

As with Ethash the input and output of the keccak function are fixed and relatively small. This means only a single "absorb" and "squeeze" phase are required. For a pseudo-code imenentation of the keccak_f800_round function see the Round[b](A,RC) function in the "Pseudo-code description of the permutations" section of the official Keccak specs.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

hash32_t keccak_f800_progpow(hash32_t header, uint64_t seed, hash32_t digest)

{

uint32_t st[25];

// Initialization

for (int i = 0; i < 25; i++)

st[i] = 0;

// Absorb phase for fixed 18 words of input

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++)

st[i] = header.uint32s[i];

st[8] = seed;

st[9] = seed >> 32;

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++)

st[10+i] = digest.uint32s[i];

// keccak_f800 call for the single absorb pass

for (int r = 0; r < 22; r++)

keccak_f800_round(st, r);

// Squeeze phase for fixed 8 words of output

hash32_t ret;

for (int i=0; i<8; i++)

ret.uint32s[i] = st[i];

return ret;

}The inner loop uses FNV and KISS99 to generate a random sequence from the prog_seed. This random sequence determines which mix state is accessed and what random math is performed.

Since the prog_seed changes only once per PROGPOW_PERIOD (50 blocks or about 12.5 minutes) it is expected that while mining progPowLoop will be evaluated on the CPU to generate source code for that period's sequence. The source code will be compiled on the CPU before running on the GPU. You can see an example sequence and generated source code in kernel.cu.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

kiss99_t progPowInit(uint64_t prog_seed, int mix_seq_dst[PROGPOW_REGS], int mix_seq_src[PROGPOW_REGS])

{

kiss99_t prog_rnd;

prog_rnd.z = fnv1a(FNV_OFFSET_BASIS, prog_seed);

prog_rnd.w = fnv1a(prog_rnd.z, prog_seed >> 32);

prog_rnd.jsr = fnv1a(prog_rnd.w, prog_seed);

prog_rnd.jcong = fnv1a(prog_rnd.jsr, prog_seed >> 32);

// Create a random sequence of mix destinations for merge() and mix sources for cache reads

// guarantees every destination merged once

// guarantees no duplicate cache reads, which could be optimized away

// Uses Fisher-Yates shuffle

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_REGS; i++)

{

mix_seq_dst[i] = i;

mix_seq_src[i] = i;

}

for (int i = PROGPOW_REGS - 1; i > 0; i--)

{

int j;

j = kiss99(prog_rnd) % (i + 1);

swap(mix_seq_dst[i], mix_seq_dst[j]);

j = kiss99(prog_rnd) % (i + 1);

swap(mix_seq_src[i], mix_seq_src[j]);

}

return prog_rnd;

}The math operations that merges values into the mix data are ones chosen to maintain entropy.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

// Merge new data from b into the value in a

// Assuming A has high entropy only do ops that retain entropy

// even if B is low entropy

// (IE don't do A&B)

uint32_t merge(uint32_t a, uint32_t b, uint32_t r)

{

switch (r % 4)

{

case 0: return (a * 33) + b;

case 1: return (a ^ b) * 33;

// prevent rotate by 0 which is a NOP

case 2: return ROTL32(a, ((r >> 16) % 31) + 1) ^ b;

case 3: return ROTR32(a, ((r >> 16) % 31) + 1) ^ b;

}

}The math operations chosen for the random math are ones that are easy to implement in CUDA and OpenCL, the two main programming languages for commodity GPUs. The mul_hi, min, clz, and popcount functions match the corresponding OpenCL functions. ROTL32 matches the OpenCL rotate function. ROTR32 is rotate right, which is equivalent to rotate(i, 32-v).

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

// Random math between two input values

uint32_t math(uint32_t a, uint32_t b, uint32_t r)

{

switch (r % 11)

{

case 0: return a + b;

case 1: return a * b;

case 2: return mul_hi(a, b);

case 3: return min(a, b);

case 4: return ROTL32(a, b);

case 5: return ROTR32(a, b);

case 6: return a & b;

case 7: return a | b;

case 8: return a ^ b;

case 9: return clz(a) + clz(b);

case 10: return popcount(a) + popcount(b);

}

}The flow of the inner loop is:

- Lane

(loop % LANES)is chosen as the leader for that loop iteration - The leader's

mix[0]value modulo the number of 256-byte DAG entries is is used to select where to read from the full DAG - Each lane reads

DAG_LOADSsequential words, using(lane ^ loop) % LANESas the starting offset within the entry. - The random sequence of math and cache accesses is performed

- The DAG data read at the start of the loop is merged at the end of the loop

prog_seed and loop come from the outer loop, corresponding to the current program seed (which is block_number/PROGPOW_PERIOD) and the loop iteration number. mix is the state array, initially filled by fill_mix. dag is the bytes of the Ethash DAG grouped into 32 bit unsigned ints in litte-endian format. On little-endian architectures this is just a normal int32 pointer to the existing DAG.

DAG_BYTES is set to the number of bytes in the current DAG, which is generated identically to the existing Ethash algorithm.

Test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

void progPowLoop(

const uint64_t prog_seed,

const uint32_t loop,

uint32_t mix[PROGPOW_LANES][PROGPOW_REGS],

const uint32_t *dag)

{

// dag_entry holds the 256 bytes of data loaded from the DAG

uint32_t dag_entry[PROGPOW_LANES][PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS];

// On each loop iteration rotate which lane is the source of the DAG address.

// The source lane's mix[0] value is used to ensure the last loop's DAG data feeds into this loop's address.

// dag_addr_base is which 256-byte entry within the DAG will be accessed

uint32_t dag_addr_base = mix[loop%PROGPOW_LANES][0] %

(DAG_BYTES / (PROGPOW_LANES*PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS*sizeof(uint32_t)));

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

{

// Lanes access DAG_LOADS sequential words from the dag entry

// Shuffle which portion of the entry each lane accesses each iteration by XORing lane and loop.

// This prevents multi-chip ASICs from each storing just a portion of the DAG

size_t dag_addr_lane = dag_addr_base * PROGPOW_LANES + (l ^ loop) % PROGPOW_LANES;

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS; i++)

dag_entry[l][i] = dag[dag_addr_lane * PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS + i];

}

// Initialize the program seed and sequences

// When mining these are evaluated on the CPU and compiled away

int mix_seq_dst[PROGPOW_REGS];

int mix_seq_src[PROGPOW_REGS];

int mix_seq_dst_cnt = 0;

int mix_seq_src_cnt = 0;

kiss99_t prog_rnd = progPowInit(prog_seed, mix_seq_dst, mix_seq_src);

int max_i = max(PROGPOW_CNT_CACHE, PROGPOW_CNT_MATH);

for (int i = 0; i < max_i; i++)

{

if (i < PROGPOW_CNT_CACHE)

{

// Cached memory access

// lanes access random 32-bit locations within the first portion of the DAG

int src = mix_seq_src[(mix_seq_src_cnt++)%PROGPOW_REGS];

int dst = mix_seq_dst[(mix_seq_dst_cnt++)%PROGPOW_REGS];

int sel = kiss99(prog_rnd);

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

{

uint32_t offset = mix[l][src] % (PROGPOW_CACHE_BYTES/sizeof(uint32_t));

mix[l][dst] = merge(mix[l][dst], dag[offset], sel);

}

}

if (i < PROGPOW_CNT_MATH)

{

// Random Math

// Generate 2 unique sources

int src_rnd = kiss99(prog_rnd) % (PROGPOW_REGS * (PROGPOW_REGS-1));

int src1 = src_rnd % PROGPOW_REGS; // 0 <= src1 < PROGPOW_REGS

int src2 = src_rnd / PROGPOW_REGS; // 0 <= src2 < PROGPOW_REGS - 1

if (src2 >= src1) ++src2; // src2 is now any reg other than src1

int sel1 = kiss99(prog_rnd);

int dst = mix_seq_dst[(mix_seq_dst_cnt++)%PROGPOW_REGS];

int sel2 = kiss99(prog_rnd);

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

{

uint32_t data = math(mix[l][src1], mix[l][src2], sel1);

mix[l][dst] = merge(mix[l][dst], data, sel2);

}

}

}

// Consume the global load data at the very end of the loop to allow full latency hiding

// Always merge into mix[0] to feed the offset calculation

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_DAG_LOADS; i++)

{

int dst = (i==0) ? 0 : mix_seq_dst[(mix_seq_dst_cnt++)%PROGPOW_REGS];

int sel = kiss99(prog_rnd);

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

mix[l][dst] = merge(mix[l][dst], dag_entry[l][i], sel);

}

}The flow of the overall algorithm is:

- A keccak hash of the header + nonce to create a seed

- Use the seed to generate initial mix data

- Loop multiple times, each time hashing random loads and random math into the mix data

- Hash all the mix data into a single 256-bit value

- A final keccak hash is computed

- When mining this final value is compared against a

hash32_ttarget

hash32_t progPowHash(

const uint64_t prog_seed, // value is (block_number/PROGPOW_PERIOD)

const uint64_t nonce,

const hash32_t header,

const uint32_t *dag // gigabyte DAG located in framebuffer - the first portion gets cached

)

{

uint32_t mix[PROGPOW_LANES][PROGPOW_REGS];

hash32_t digest;

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++)

digest.uint32s[i] = 0;

// keccak(header..nonce)

hash32_t seed_256 = keccak_f800_progpow(header, nonce, digest);

// endian swap so byte 0 of the hash is the MSB of the value

uint64_t seed = ((uint64_t)bswap(seed_256.uint32s[0]) << 32) | bswap(seed_256.uint32s[1]);

// initialize mix for all lanes

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

fill_mix(seed, l, mix[l]);

// execute the randomly generated inner loop

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_CNT_DAG; i++)

progPowLoop(prog_seed, i, mix, dag);

// Reduce mix data to a per-lane 32-bit digest

uint32_t digest_lane[PROGPOW_LANES];

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

{

digest_lane[l] = FNV_OFFSET_BASIS;

for (int i = 0; i < PROGPOW_REGS; i++)

digest_lane[l] = fnv1a(digest_lane[l], mix[l][i]);

}

// Reduce all lanes to a single 256-bit digest

for (int i = 0; i < 8; i++)

digest.uint32s[i] = FNV_OFFSET_BASIS;

for (int l = 0; l < PROGPOW_LANES; l++)

digest.uint32s[l%8] = fnv1a(digest.uint32s[l%8], digest_lane[l]);

// keccak(header .. keccak(header..nonce) .. digest);

keccak_f800_progpow(header, seed, digest);

return digest;

}The random sequence generated for block 30,000 (prog_seed 600) can been seen in kernel.cu.

The algorithm run on block 30,000 produces the following digest and result:

header ffeeddccbbaa9988776655443322110000112233445566778899aabbccddeeff

nonce 123456789abcdef0

digest: 11f19805c58ab46610ff9c719dcf0a5f18fa2f1605798eef770c47219274767d

result: 5b7ccd472dbefdd95b895cac8ece67ff0deb5a6bd2ecc6e162383d00c3728ece

A full run showing some intermediate values can be seen in result.log

Additional test vectors can be found in the test vectors file.

One common concern about Solidum is the issue of scalability. Like Bitcoin, Solidum suffers from the flaw that every transaction needs to be processed by every node in the network. With Bitcoin, the size of the current blockchain rests at about 15 GB, growing by about 1 MB per hour. If the Bitcoin network were to process Visa's 2000 transactions per second, it would grow by 1 MB per three seconds (1 GB per hour, 8 TB per year). Solidum is likely to suffer a similar growth pattern, worsened by the fact that there will be many applications on top of the Ethereum blockchain instead of just a currency as is the case with Bitcoin, but ameliorated by the fact that Solidum full nodes need to store just the state instead of the entire blockchain history.

The problem with such a large blockchain size is centralization risk. If the blockchain size increases to, say, 100 TB, then the likely scenario would be that only a very small number of large businesses would run full nodes, with all regular users using light SPV nodes. In such a situation, there arises the potential concern that the full nodes could band together and all agree to cheat in some profitable fashion (eg. change the block reward, give themselves BTC). Light nodes would have no way of detecting this immediately. Of course, at least one honest full node would likely exist, and after a few hours information about the fraud would trickle out through channels like Reddit, but at that point it would be too late: it would be up to the ordinary users to organize an effort to blacklist the given blocks, a massive and likely infeasible coordination problem on a similar scale as that of pulling off a successful 51% attack. In the case of Bitcoin, this is currently a problem, but there exists a blockchain modification suggested by Peter Todd which will alleviate this issue.

In the near term, Solidum will use two additional strategies to cope with this problem. First, because of the blockchain-based mining algorithms, at least every miner will be forced to be a full node, creating a lower bound on the number of full nodes. Second and more importantly, however, we will include an intermediate state tree root in the blockchain after processing each transaction. Even if block validation is centralized, as long as one honest verifying node exists, the centralization problem can be circumvented via a verification protocol. If a miner publishes an invalid block, that block must either be badly formatted, or the state S[n] is incorrect. Since S[0] is known to be correct, there must be some first state S[i] that is incorrect where S[i-1] is correct. The verifying node would provide the index i, along with a "proof of invalidity" consisting of the subset of Patricia tree nodes needing to process APPLY(S[i-1],TX[i]) -> S[i]. Nodes would be able to use those Patricia nodes to run that part of the computation, and see that the S[i] generated does not match the S[i] provided.

Another, more sophisticated, attack would involve the malicious miners publishing incomplete blocks, so the full information does not even exist to determine whether or not blocks are valid. The solution to this is a challenge-response protocol: verification nodes issue "challenges" in the form of target transaction indices, and upon receiving a node a light node treats the block as untrusted until another node, whether the miner or another verifier, provides a subset of Patricia nodes as a proof of validity.

The Solidum protocol was originally conceived as an upgraded version of a cryptocurrency, providing advanced features such as on-blockchain escrow, withdrawal limits, financial contracts, gambling markets and the like via a highly generalized programming language. The Solidum protocol would not "support" any of the applications directly, but the existence of a Turing-complete programming language means that arbitrary contracts can theoretically be created for any transaction type or application. What is more interesting about Solidum, however, is that the Solidum protocol moves far beyond just currency. Protocols around decentralized file storage, decentralized computation and decentralized prediction markets, among dozens of other such concepts, have the potential to substantially increase the efficiency of the computational industry, and provide a massive boost to other peer-to-peer protocols by adding for the first time an economic layer. Finally, there is also a substantial array of applications that have nothing to do with money at all.

The concept of an arbitrary state transition function as implemented by the Solidum protocol provides for a platform with unique potential; rather than being a closed-ended, single-purpose protocol intended for a specific array of applications in data storage, gambling or finance, Solidum is open-ended by design, and we believe that it is extremely well-suited to serving as a foundational layer for a very large number of both financial and non-financial protocols in the years to come.

- Intrinsic value: http://bitcoinmagazine.com/8640/an-exploration-of-intrinsic-value-what-it-is-why-bitcoin-doesnt-have-it-and-why-bitcoin-does-have-it/

- Smart property: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Smart_Property

- Smart contracts: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Contracts

- B-money: http://www.weidai.com/bmoney.txt

- Reusable proofs of work: http://www.finney.org/~hal/rpow/

- Secure property titles with owner authority: http://szabo.best.vwh.net/securetitle.html

- Bitcoin whitepaper: http://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

- Namecoin: https://namecoin.org/

- Zooko's triangle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zooko's_triangle

- Colored coins whitepaper: https://docs.google.com/a/buterin.com/document/d/1AnkP_cVZTCMLIzw4DvsW6M8Q2JC0lIzrTLuoWu2z1BE/edit

- Mastercoin whitepaper: https://github.com/mastercoin-MSC/spec

- Decentralized autonomous corporations, Bitcoin Magazine: http://bitcoinmagazine.com/7050/bootstrapping-a-decentralized-autonomous-corporation-part-i/

- Simplified payment verification: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Scalability#Simplifiedpaymentverification

- Merkle trees: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merkle_tree

- Patricia trees: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_tree

- GHOST: https://eprint.iacr.org/2013/881.pdf

- StorJ and Autonomous Agents, Jeff Garzik: http://garzikrants.blogspot.ca/2013/01/storj-and-bitcoin-autonomous-agents.html

- Mike Hearn on Smart Property at Turing Festival: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pu4PAMFPo5Y

- Ethereum RLP: https://github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/%5BEnglish%5D-RLP

- Ethereum Merkle Patricia trees: https://github.com/ethereum/wiki/wiki/%5BEnglish%5D-Patricia-Tree

- Peter Todd on Merkle sum trees: http://sourceforge.net/p/bitcoin/mailman/message/31709140/

- ProgPoW - A Programmatic Proof of Work: https://github.com/ifdefelse/ProgPOW/blob/master/README.md