This session is about tools and methods (section 1.) that make it easy to organize, share, reproduce, and maintain your scientific computations and collaborate with others on code & projects (s. 2.). Self-guided exercises are found in s. 3. Real-life examples are provided to illustrate version-control in practice (s. 4.). Additional resources are listed at the end.

Table of contents

-

- Set Up Your Project Using Version Control

-

- Maintain And Reproduce Your Project Results

-

- Self-Guided Exercises (using binder cloud)

-

- Examples from EAPS & collaborators

-

- Additional Resources

Ahead of this session, it is suggested that you create a github.com account if you do not have one yet. The github guides provide very useful examples. Our Exercise #0 in fact is just their Hello World guide -- a great way to get ready.

After this session, please consider helping us improve the repo material by e.g. reporting potential bugs, typos, broken links, oversights, etc. via our issue tracker or suggest changes via pull requests. This repo itself is an example of the framework described in this session -- the project was built collectively and welcomes new contributors.

|

|

|---|---|

|

- Introducing Github, which is basically: git (version control) + social networking + apps / cloud services

- Get started with GitHub & command-line git in Exercise 0

- Get more familiar with command-line tools (Exercises 1, 2)

- Examples of how organizations use Github: MITgcm (mature Fortran example), JuliaDynamics (fairly mature Julia example), JuliaClimate (early stages of development Julia example)

- Repository (repo) examples: MITgcm repo, JuliaDynamics repo, JuliaClimate repo

- Application (App) examples: GitHub Help, zenodo, Travis CI

Linked repos should illustrate how pull requests, git commits, issue trackers, stars, etc provide user-friendly tools to collaborate on computational projects, document codes, their evolution, related discussions, etc., get feedback, bug reports, help, etc., ... from users, and maintain established capabilities through time. while software evolves and contributors may come and go. Don't hesitate to get involved e.g. using issue trackers.

- Version Control: backing up your code in a structured way that fosters open-source collaboration

- Version control; e.g. git-handbook tutorial from GitHub

- in Exercise 3 you set up a practical collaborative framework for the workshop repo

- the github GUI (e.g. file history, blame, commits, forks, PRs; see repo examples)

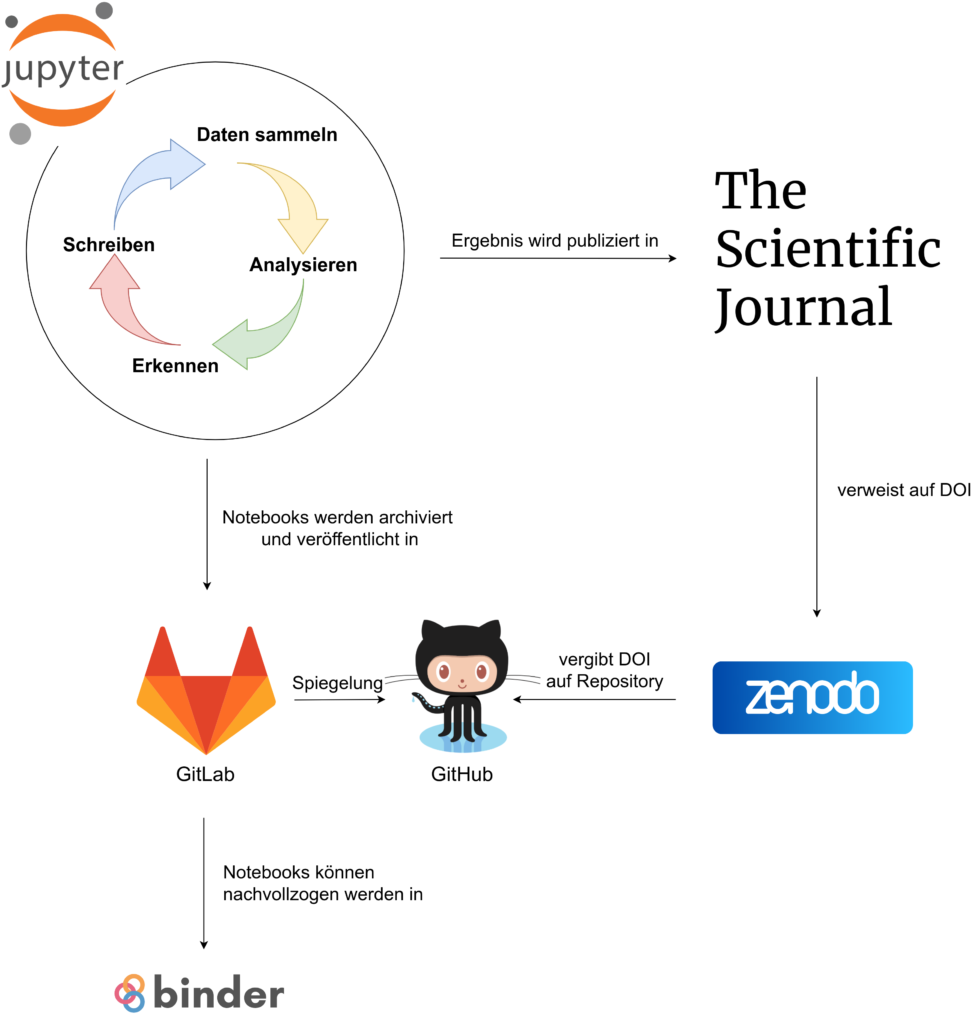

- semantic versioning, GitHub releases, Digital Object Idenfifier (DOI), e.g. zenodo.org

- In Exercise 4 you create a

Juliapackage and set up version control for it.

Version control is a widely used approach to documenting file changes through time. git is a big part of it but there is more to it!

- Documentation: how to make your code readable, understandable, and extendable for users (including your future self!)

- Mastering Markdown; e.g., MacDown app for macOS

- Documenter.jl & docstrings in Julia (for Python, see lecture 2; for Matlab / Octave see 1, 2, 3)

- reStructuredText and readthedocs as an alternative for e.g. a model configuration or source code

Pull requests, issues, star, watch, etc. on Github.com are also a form of documentation (e.g. in repo examples), as they transparently document bugs, updates, and various development choices that drive software changes.

In Exercises 1, 2 you already started doing version control using command line git. Exercise 3 focuses on collaboration development, but version control can be useful for all sorts of shared or private repositories. After a while it may become a reflex to do it for all codes that you won't immediately throw away. This approach is very commonly used for packages (see below) and git is suitably designed for small text files (e.g., plain julia code). However, other services apply a similar approach to data sets (e.g., dataverse), papers (e.g., overleaf), and jupyter notebooks can be converted to plain code (e.g., jupytext).

- Regression / unit testing: continuous component-by-component testing is key to developing robust and resilient code

- in Exercise 2 you run examples

- in Exercise 4 you make your own

- automating tests, in the cloud, is made easy by e.g. Travis CI

Regression testing often goes something like this: create reference result, formulate comparison with reference result, implement test & automate; check test results before comitting code changes (or merging a PR). This very common approach is often required for packages (see below). However, you can also do this to ensure that a model solution re-run accurately reproduces the original (e.g., see Forget et al. 2015 & this doc) or indeed for any other computation (e.g. in lecture 2).

- Packages: to reach the stars (of scientific computing), stand on the shoulders of giants

- Here is a Julia example. For

Python, see lecture 2. For GNU Octave /Matlabsee this doc. - In Exercise 4 you create, version control, upload, and archive a

Juliapackage. - Section 2 touches on registries, archives, hosting, and continuous integration.

- In

Julia, we use Pkg.jl & e.g. PkgTemplates.jl. InPython, we use conda, pip, etc.

- Here is a Julia example. For

So-called environmments and compatibility constraints are general approaches to deal with dependencies across a galaxy of packages that may all evolve simultaneously in parallel. Packages are a bit of a special case but the same information can in principle be attached to any project. In this repo this information is put inside the binder/ folder (e.g. in the *.toml files for julia). This allows mybinder.org to know what packages, and versions should be installed in the jupuyterlab instance so that all users have the same environment.

- Archiving and registering: share your hard work with others – and get some well-deserved credit!

- Making Your Code Citable

- Dataverse or zenodo for data sets; archived = D.O.I.'ed

- registering packages; e.g.

Julia's package registries - Julia registrator and tag bots / apps

It's important to distinguish between simply hosting a data set and archiving it. An archive must have a permanent identifier and a long-term commitment by the host. This is what dataverse, or zenodo, provide and a crucial element to ensure long-term reproducibility. With this being said, simply making your project inputs and outputs publicly available is a great start! Cloud storage included in free plans from various cloud providers (e.g. dropbox, aws, & google) often suffice for small projects.

- Maintainance & user support: ensuring your code's life beyond its original use

- Mastering Issues & Mastering Forks

- Keep up with pull requests & issues

- Keep up with dependency updates

- Regular, continued unit testing

- Exploit debuggers like this one

Collaborators, modularity, documentation, good coding practices, etc can all play an important role. The collaborative set up in Exercise 3 often facilitates the integration of code updates between projects and across forks. It can also be important to choose your dependencies carefully -- e.g. you might want to assess whether it is likely that a given dependency will be well maintained / remain functional in the future before choosing whether you should use that dependency.

All of the exercises can be done using the cloud-based environment provided in the workshop material. Just hit the binder badge in the workshop landing page to get it started.

This method is freely provided by mybinder.org and it uses the jupyterlab interface in your web browser (tip: the Google Chrome browser seems to work best for this). You can also use your own computer if that's more convenient though.

List Of Exercises

-

- Hello GitHub World

-

- Command Line Git

-

- Command Line & Unit Tests

-

- Practical Collaboration Setup

-

- Create A Package And Collaborate

-

- A Version-Controled Julia Project

-

- Track Changes Using Jupytext

Follow the directions in the Hello World guide. This guide will lead you to set up a GitHub.com account and start using git for Version control. This framework is very widely used and the focus of this session. Further along in the Hello World guide, you will learn to use git to track repositories (repos). You can think of repos as folders and dowload (clone) them to any computer. GitHub.com is something like git + social networking + apps / cloud services.

In the Jupyterlab launcher pane click on terminal. A window should open where you will be able to type shell command lines. For example you can dowload / clone the workshop repository from GitHub.com like this:

cd ~

git clone https://github.com/PraCTES/MIT-PraCTES

ls -la MIT-PraCTES/

The final command (ls ...) lists everything inside the local copy of MIT-PraCTES/. It should reveal a subfolder called .git/ because version control has been set up for this repo. The .git/ folder is where git operates its magic. The binder/ folder is where we put information about the cloud environment that you are using. The demos/ folder should contain the present file. etc.

Next, let's create a new folder (mkdir test20200117) and start tracking its contents (git init).

cd ~

mkdir test20200117

cd test20200117

ls -la

git init

ls -la

Typing the command ls -la before and after git init shows the appearance of the hidden .git/ folder, which is where all of the internal files git uses to track changes live.

Now, we will add a file to the folder and commit it to the git's memory. The following command The command echo "Hi there" > readme creates a short text file called readme; git add then tells git about it; and git commit records the content of the file -- at this point readme is now in the version control system. The final command git commit -m "initial_commit" should ask for a username and email at least once -- this is the key information that git uses for its book-keeping and to attribute authorship inside the .git/ folder. Follow the instrucitons to configure git so that it knows who you are. (Note: Try git status before and after each of the commands -- the printed message should go from Untracked to new file to nothing to commit.)

echo "Hi ther" > readme

git add readme

git commit -m "initial commit"

Next, let's modify the new readme file by correcting the typo in the text and commit the changes. Open readme using the jupyterlab menu bar (File > Open from Path... > test20200117/readme), e.g. add an e after ther, and save the modified file. Now go back to the terminal window and type git commit readme. You will be prompted to provide a commit message by the pre-installed nano editor. Enter some text then hit ^X to exit, y to confirm, and the Return key to finish.

Now you can reveal what has been recorded by the version control system using the git log command. A list of recent commits should appear -- there should be two at this point. Next to each commit in the list there is a long sort of code (an hexadecimal). If you copy it and paste after git show then you should get more information about that commit.

To finish you can upload the repository you just created at the command line by following these instructions. This invoves the GitHub.com GUI, and then git remote & git push at the command line. Note that you have already done the git init and git commit parts here.

Download, compile, and run MITgcm on one of the unit tests:

$ cd ~

$ git clone https://github.com/MITgcm/MITgcm

$ cd MITgcm/verification/

$ ./testreport -t advect_cs

Download a Julia package (e.g. MeshArrays.jl) from github and start julia.

$ git clone https://github.com/gaelforget/MeshArrays.jl

$

$ julia

_

_ _ _(_)_ | Documentation: https://docs.julialang.org

(_) | (_) (_) |

_ _ _| |_ __ _ | Type "?" for help, "]?" for Pkg help.

| | | | | | |/ _` | |

| | |_| | | | (_| | | Version 1.3.1 (2019-12-30)

_/ |\__'_|_|_|\__'_| | Official https://julialang.org/ release

|__/ |

julia>

This is the basic julia mode where you can execute operations (e.g. try julia> 1+1 & the Return key). One can access the package manager mode by typing the ] key. Then pkg> add MeshArrays.jl & the Return key will add the chosen package to the Julia environment.

In package manager mode (]), one can then run the unit tests for this package using test MeshArrays. If all unit tests were successful, the final display should look something like this:

Testing MeshArrays

Resolving package versions...

Status `/tmp/jl_8pEyMo/Manifest.toml`

[81a5f4ea] CatViews v1.0.0

[cb8c808f] MeshArrays v0.2.4

...

Test Summary: | Pass Total

MeshArrays tests: | 15 15

Testing MeshArrays tests passed

To leave the package mode and go back to the basic julia> prompt hit the Esc keystroke (or Backspace / Delete if that does not work). You can then start using the Mesharrays.jl package that we just been added. For example:

julia> using MeshArrays

julia> (Rini,Rend,DXCsm,DYCsm)=MeshArrays.demo2()

julia> show(Rend)

To access the documentation of a function in Julia one can just type ? followed by e.g. the name of the package / module followed by the function name (e.g. ?MeshArrays.demo2). This will print out the docstring which is inside the package code, just next to the demo2 function definition (see the julia docs for detail).

help?> MeshArrays.demo2

demo2()

Demonstrate higher level functions using smooth. Call sequence:

(Rini,Rend,DXCsm,DYCsm)=MeshArrays.demo2();

Now let's look inside the Julia package we have downloaded. We see a .git as before but also a documentation folder, docs/, and the src/ folder where the code is. The *.toml files document the package dependencies and the .travis.yml file is used to automate the unit testing via the https://travis-ci.org/ cloud service.

$ ls -la MeshArrays.jl/

total 52

...

drwxr-xr-x 4 jovyan root 4096 Jan 17 14:50 docs

drwxr-xr-x 8 jovyan root 4096 Jan 17 14:50 .git

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 82 Jan 17 14:50 .gitignore

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 1163 Jan 17 14:50 LICENSE.md

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 1429 Jan 17 14:50 Manifest.toml

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 464 Jan 17 14:50 Project.toml

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 2457 Jan 17 14:50 README.md

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 10 Jan 17 14:50 REQUIRE

drwxr-xr-x 2 jovyan root 4096 Jan 17 14:50 src

drwxr-xr-x 2 jovyan root 4096 Jan 17 14:50 test

-rw-r--r-- 1 jovyan root 1430 Jan 17 14:50 .travis.yml

If you go to the repo on github.com then the landing page should show a README.md (scroll down maybe) with a build badge. Clicking on this badge will get you to the results of automated unit tests generated using the https://travis-ci.org/ cloud service. The docs badge will in turn lead you to the hosted documentation based on what's in docs/.

To take this exercise a git further, let's now install a registered package by typing ] then add IndividualDisplacements.jl. Notice that julia's package manager takes care of the git clone part for registered packages. Wondering where the package got downloaded? Press esc then type pathof(IndividualDisplacements) to find out.

Finally:

- To display the list of packages currently installed : type

]thenstatus(orstfor short). - To remove a package from

julia:]then e.g.rm IndividualDisplacements.jl.

The approach described in the MITgcm manual typical of a practical and collaborative model. The basic configuration is depicted below and your exercise is to set this up for this workshop's own repo, https://github.com/PraCTES/MIT-PraCTES.

To this end, you will first fork (github), clone (terminal), and branch (terminal) as explained here. Then, in the terminal window, execute the following command:

git remote add upstream https://github.com/PraCTES/MIT-PraCTES

This will allow you to

-

- modify files (such as the code demos) and commit these changes to your local branch (on your laptop, e.g. all offline)

-

- push your branch back to your repo on

Github.comand possibly see your changes merged in the upstream repo repo via a pull request.

- push your branch back to your repo on

But imagine a scenario where multiple people are doing this and code changes happen in the main repo while you were in the middle of doing your changes to the code? No panic -- that is why the schematic below shows a connection between upstream and your local clone.

The pull upstream command effectively brings the latest updates from the main repo to your local copy / clone. This will then allow you to merge these updates from upstream into your local branches, and then push them to your online repo (see this doc). We will do this in Exercise #4b using a practice repo.

Create a julia package, add tests, add docs, and push to your github account following this guide

Let's re-use your repos from Exercise 4a and use them to try out collaborative development mechanisms.

-

- Pair up with another workshop attendee

-

- Proceed as in Exercise 3 using their repo as

main repo(and vice versa for them).

- Proceed as in Exercise 3 using their repo as

-

- In your clone of their repo, create a branch, add a new file, and

git commit.

- In your clone of their repo, create a branch, add a new file, and

-

- Use

git pushandPull Requestto submit your proposed changes to them. ThePRshould point from the modified branch in your fork to the master branch in the main repo onGitHub.com.

- Use

-

- They can now

mergeyour pull request into theirmasterbranch.

- They can now

-

- To finish you want to update the

masterbranch in your fork as explained here.

- To finish you want to update the

Note: you can also do the command-line git part using your own laptops.

Here is a Julia code sample where we define a new xy type and then redefine sum for this new type. This corresponds to what was done in lecture 2 in Python where we defined objects and methods. In this exercise we will turn this code snippet into a version-vontroled project hosted on github.com and easily reproduced on mybinder.org.

#Define a new data type with two real numbers

struct xy

a::Float64

b::Float64

end

#Define a variable of the new data type

ab=xy(1.0,2.0)

typeof(ab)

show(ab)

#The following command would return an error message at this point

#because julia does not now yet how to compute the sum of ab

#sum(ab)

#We want to define a special version of the sum function

#that applies when the input type is `xy` (`::xy` in Julia)

import Base:sum

function sum(ab::xy)

ab.a+ab.b

end

#Now this works:

sum(ab)

In Julia terminology, the function sum in the provided example disptaches to the method where the type of the sole input is annotated as xy. Notice how this resembles but also differs from what we did in lecture 2 in Python. Some of the key aspects in which Julia differs from Python include: functions v objects, multiple dispatch, type annotations, broadcasting. But there are also lots of similarities.

- open a julia notebook

- copy the above code in the notebook

- Verify at the end that

sum(xy(1.0,2.0))==3.0is true - save to file (e.g.

xysum.ipynbcould be its name)

- open a terminal window

- create a new folder, move

xysum.ipynbto this folder - copy the

binder/*.tomlfiles to the new folder - setup version control (

git) for this folder - git add and commit the folder's three files

- create a new repo on

GitHub.com git pushyour project to thisgithub.comrepo- rerun the project using

mybinder.org& thegithub.comrepo - take a minute to celebrate?

Let's add another type and method to your project. Now we want to plot a curve and set the vertical axis range automatically -- based on the min and max embeded in each RangeArray instance.

- In a new notebook, first add the

Plots.jlpackage and theRangeArraytype (see below). - Create a special version of the

plotfunction for theRangeArraytype. - Add a docstring juat before the new

plotmethod is defined. - Provide a visual example of the new

plotmethod working at the end. - Then proceed as in

5.1&5.2

struct RangeArray

arr::Array

min::Float64

max::Float64

end

Install and try jupytext in the Jupyter lab environments or on your laptop. Using the paired light scripts appraoch where .jl files are kept in sync with your notebooks (as in this example) can make it easier to trace back changes made to jupyter notebooks using git and github.

Here we focus on examples that we know well and feel illustrate some of the the approaches outlined in this lecture -- each example in its own, often imperfect ways. Many, many other examples are available on GitHub.com and elsewhere. Every project may do things slightly differently, so it's great look around for other examples. Don't hesitate to open an issue on the workshop repo if you find a good example you'd like to see listed in this doc.

- The MIT general circulation model (

MITgcm) is a widely used numerical model that simulates the Ocean circulation and related processes. It has been developed collaboratively by a community distributed around the world over 20+ years. Lead developer @jm_c and the community at large have been maintaining the model functionalities and reproducing its reference results all along (e.g. Exercise 2), while revising and extending the code base at the same time, and continuously welcoming new contributors. - ECCO version 4 is a global ocean state estimation framework that uses

MITgcmas a dependency. HereGitHub.cometc is used to provide and document the model configuration. This allows anyone with access to e.g. a small cluster to easily rerun realistic model solutions generated as far as now 4 years ago. The repo also includes a testing mechanism to verify that reruns reproduce the original solution accurately. The model input, as needed to rerunECCOv4r2usingMITgcm, is permanently archived in the Harvard Dataverse along with the reference model output from 2016. - Forget & Ferreira 2019 is a study that in turn uses

ECCOv4r2output as a dependency. The new study results were also archived in this dataverse and the Helmholtz Decomposition method needed to recreate the new results is now available both in this Matlab / Octave package and in this Julia package. Try it out e.g. using binder and notebooks in this repo! - Hausfather, Drake, Abbott, & Schmidt 2019 is another example that relies on a different set of dependencies. Here the authors evaluate the performance of past climate model projections. This repository contains the notebooks, scripts, and data that correspond to the analysis in the paper.

Pythondependencies are listed in theenvironment.ymlin this case. Hence you can again usebinderto rerun the analysis in the cloud.

In any of the examples, and beyond, you are very welcome to get involved. For example, please consider:

- using the watch, star, or fork functionalities on the

github.comrepos. - contributing via the repo

issue trackers(for questions, bug reports, etc). - helping maintain, improve, or extend these projects via

forksandpull requests.

- Check out these other tools: aws, docker, slack, overleaf, nextjournal, jupytext, youtube, ...

- https://opensource.guide/how-to-contribute/

- https://www.youtube.com/user/JuliaLanguage

- mybinder.org by itself

- https://julialang.org/learning/

- Besides github: bitbucket, gitlab, etc.

- Besides jupyter: e.g. atom and juno