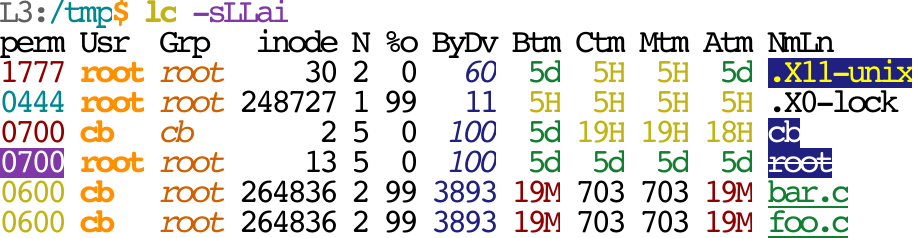

For the impatient, here is a screenshot (NOTE: my terminal is set up to embellish bold text with dark orange and italic with light orange which is..uncommon at best.):

Getting an lc config going should be as easy as (on Debian):1

apt install nim #(https://nim-lang.org/ has other options)

nimble install lc

though the Nim experience can sometimes have fairly rough-hewn edges. Worst case you can just build the nim compiler from source in a large one-liner that takes a minute or two.2

One maybe interesting 2-level sort-colorized listing (etc/lc has details) is:

~/.nimble/bin/lc -oDd /dev

This program is not and never will be a drop-in replacement for ls at the CLI

option compatibility level. ls is a poorly factored mishmash of selection,

sorting, and formatting options. With fewer CLI options (but beefier configs)

lc is many-fold more flexible. It can create similar output, but my main

impetus to write lc was always a better functionality factoring not mere

recapitulation. So, lc is not just "ls in Nim". If you want ls, it has

big companies supporting it & isn't going anywhere.

lc is also not stat or find. Those have their roles for spot-checking or

generating program-consumed data streams. lc is about human-friendly output,

helping you see and/or create organization you want in your file sets and shine

light on unexpected things as you go about everyday business listing your files.

As such, absolute max performance is not a priority as human reaction time is

not so fast & very large directories are usually ill-advised.

Enough disclaimers about what lc is not. What is lc? Why do we need

yet another file lister? What's the point? Well, lc

-

is clearly factored into independent actions and very configurable with good CLI ergonomics (unique prefixes good enough, spellcheck, etc.)

-

supports multi-level sorting for many forward/reverse attributes

-

supports arbitrary assignment of "file kind order" for use in sorting (note how, in the screenshot, dot-directories precede dot files precede directories precede regular files)

-

supports a kind/type-vector for multi-dimensional reasoning, including text attribute layers and an "icon vector" (for utf8 "icons", anyway)

-

supports from nanosecond file times to very abbreviated ages

-

has value-dependent coloring for file times, sizes, permissions, etc.

-

can emit "hyperlink" escape codes to make entries clickable in some terminals

-

supports file/user/group/link target abbreviation via

-mNum, etc. -

supports "local tweak files" - extra config options in a local

.lc(or a.lcin a shadow tree under a user's control if needed). Nice to eg, avoid NFS automounts or inversely to engage expensive classification, for dirs with special sorts, formats, .. -

supports "theming" (operationally, environ-variable-keyed cfg includes)

-

supports latter-day Linux statx/b)irth times

-

supports

file(1)/libmagicdeep file inspection-based classification (though using this with large directories can be woefully slow) -

is extensible with fully user-defined file type tests & field formats

With so many features you might think lc is huge, but it is also compact

(~900 non-comment/blank lines; ~300 is just code dispatch tables & help, ~650 in

cligen/[tab, humanUt, abbrev] might be in lc had I not done both pkgs) with

only cligen and the Nim stdlib as dependencies.

The trickiest idea is (likely) "multi-dimensional". I mean this in an abstract "INDEPENDENT coordinate" sense not a Jurassic Park (1993)-esque IRIX fsn graphical file browser sense. Examples of slots/dimensions/attributes may help.

In the screenshot at the top of this text, "foo.c" and "bar.c" are both source

code files (highlighted green) and hard-links (underlined) to each other.

Similarly, "/tmp/root" is a directory - so it is WHITE on_blue - but

inaccessible to the user running lc and so "struck through" text. This all

matters since listing files is often a precursor to acting upon them.

Most any terminal can set text fore- & background colors independently. I happen to like st for its hackability. That can also bold, italic, blink, underline, struck, and inverse independently. (Color inversion involves a mapping too complex to be a very useful visual aid.) So, 8 usable output dimensions, 6 shallow 1-bit dimensions + fg/bg color with larger value ranges. While subjective, I find it not hard to distinguish text with all those attributes varying. Geographical map folk often call this "layering" (such as political borders layered atop satellite imagery).

The input/data side has many independent fields & bits. While dirent.d_type

is a mutually exclusive type code (like directory/named pipe/..), most types

aren't. E.g., a file can be both an executable regular file and

some kind of script source or both a directory and a directory with a sticky bit

set. Independently of all that, it can begin with a '.' or not. Add all of

struct stat and deep file header inspection and the type space explodes both

in kinds & independent sub-kinds/dimensions (stripped|not, 32|64-bit, etc.).

Only end users can prioritize use of precious few output layers to represent the

huge space of input kinds.

This may sound daunting, but other highlighting systems follow this model - e.g.

a misspelled word bolded inside an elsewise colorized source code comment. lc

simply explicitly models this structure to try to enable better allocation by

end users over more dimensions than just 2 (misspelling, comment) due to diverse

file types. Most briefly, lc aids "aligning" rendered output traits with

classified input traits.3

As for the bread and butter of file listing, many things that are hard-coded in

other file listers are fully user-defined in lc, like a concept of dot files.

Assuming you define a "dot" or "dotfile" type lc -xdot will probably exclude

those from a listing. (Unique prefixes being adequate may mean a longer string

if you define other file kinds with names starting with "dot".)

I usually have an alias that does -xdot and a related one ending with an "a"

that does not. That mimics ls usage. If the listing is well organized,

seeing dot files by default may be considered as much a feature as a bug.

Including everything by default lets "dot" be user-defined.

You can also do -idot to list only the dot files (or any other user/system

defined file kind) which is not something available in most file listers. It's

also not always easy to replicate via shell globbing the input list. Eg., lc -r0 -idir -iodd in my config can be illuminating on very aged file trees.

Multi-level sorting and user format strings are similar ideas to other tools

like the Linux ps, stat -c, and find -printf. Sorting by file kind is

possible and "kind order" is user-configurable. Between kind order assignment

and multi-dimensionality you can filter & group almost any way that makes sense,

and none of that needs any hacking on lc proper - just your configuration.

Less can be more with good factoring. lc is more an "ls framework".

Because of all that flexibility, lc has a built in style/aliasing system.

This lets you name canned queries & reports and refer to them, like lc -sl.

My view is that there is no one-size-fits-all-or-even-most long-format listing.

ls -sl or a shorter ll='lc -sl' alias is the way to go. Then you can make

columns included (and their order, --header or not, ..) all just how you

like. I usually like 5 levels of long-ness, not 2, in my personal setup in

configs/cb0/config (& files included there).

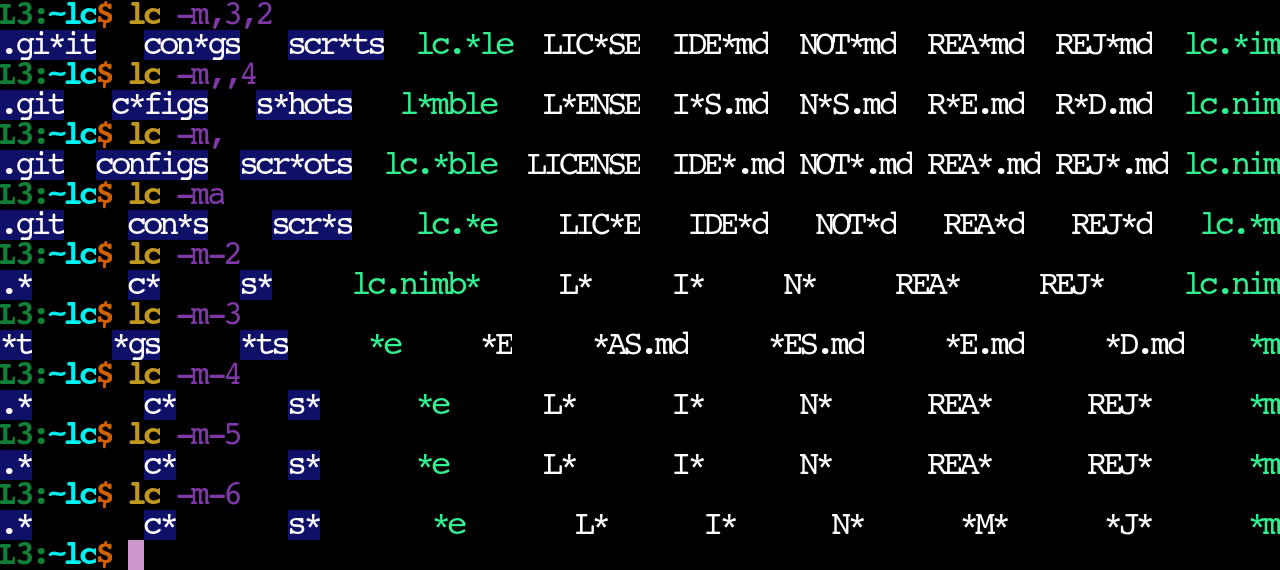

A feature I don't know of any terminal file listers using is abbreviation (GUIs

have this, though and PowerShell9k/10k in single-path prompt contexts). Most

everyone has probably been annoyed at one time or another by some pesky few

overlong filenames in a directory messing up column widths in a file listing.

lc -m16 lets you limit displayed length to 16 (or whatever) characters.

lc replaces the (user-definable) "middle slice" with a user-definable string.

While you can use some UTF8 ellipsis, you probably want * since that choice

will make most abbreviations copy-pasteable shell patterns.

Manual width & slice selection may not result in patterns that expand uniquely,

but lc has you covered with a variety of automatic abbreviation options that

are unique: specified head|tail, mid-point (for those 2 just leave "," fields

blank), unique best-common-point (start width with "a"), unique prefix (-2) or

suffix (-3), the shorter *fix (-4), the shortest 1-star-anywhere (-5) and

shortest 2-star (-6). E.g.,

(or see a bigger example )

There are similar -U, -G, -M for user user names, group names, and symlink

targets. While shells will not expand * in user/group names, you can change

the separator to something else or even the empty string to save terminal

columns as in -U4,,, and have a little grep <PASTE> /etc/passwd helper.

Auto modes are not yet available for symlink targets since when they matter most they are a bit expensive (requiring minimizing patterns over whole directories for every path component).

In many little ways, lc tries hard to let you manage terminal real estate,

targeting max information per row, while staying within an easy to visually

parse table format. Features along these lines are terse 4 column octal

permission codes, rounding to 3-column file ages, 4 column file sizes.

If it is too dense, you can have fewer, more spaced out columns with lc -n4 or

similar. If it is too sparse, you can use -m, drop format fields or

identify the most effective rename targets with lc -w5 -W$((COLUMNS+10)) which

shows the widest 5 files in each output column formatted as if you had 10 more

terminal cols. A hard-to-advocate-but-possible way to save space is lc -oL.

Try it. { I suspect this minimizes rows within a table constraint, but the proof

is too small to fit in the margin. ;-) Maybe a 2D bin packing expert can weigh

in with a counter example. }

In the other direction, lc supports informational bonuses like ns-resolution

file times with %1..%9 extensions to the strftime format language for

fractions of a second to that many places, rate of disk utilization

(512*st_blocks/st_size = allocated/addressable file bytes), newer Linux

statx attributes and birth times, and more.

lc also comes with boolean logic combiners for file kind tests, many built-in

tests, and is extensible for totally user-defined tests and formats. If there's

just a thing or two missing then you can likely add it without much work. Given

human reading time and fast NVMe devices, even doing "du -s" inside a format is

not unthinkable, though unlikely to be a popular default style. Hard-coding Git

support seems popular these days. I don't do that yet. I'm not sure I want a

direct dependency, but you may be able to hack something together.

Footnotes

-

You may need

PATH|MANPATHchanges. Orman -l path/to/lc.1can work. ↩ -

git clone https://github.com/nim-lang/Nim; git clone https://github.com/c-blake/cligen; git clone https://github.com/c-blake/lc; cd Nim; sh build_all.sh; cd ../lc; ../Nim/bin/nim c -d=danger -p=../cligen lc; cp -pr configs/cb0 $HOME/.config/lc; ./lc↩ -

Operationally, users just pick small integer labels for kinds aka series of order-dependent tests aka classes. The first passing kind test within a dimension wins that dimension. To aid debugging kind assignments you can do things like

lc -f%0%1%2%3%4%5\ %fto see coordinates in the first 6 dims. The inspiration for this system was having "dot-file directories" sorted in a block before all dot regular files, but it is obviously much more general. ↩