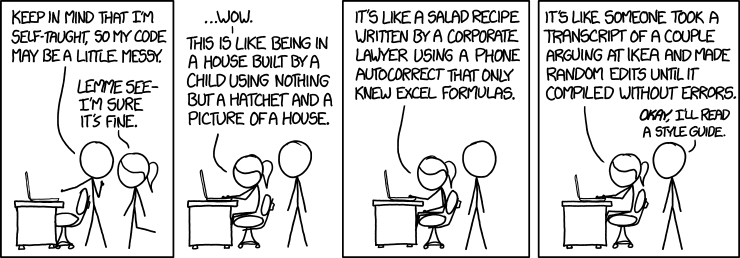

All the material in this course so far was just too define "the rules" of Python. But writing good code means more than just knowing the rules that define a language. You can probably teach a clever six-year-old to use a hatchet, but that doesn't mean you'd want to live in a log cabin they built. A lot of knowledge, skill, and practice are needed to become a master craftsman. This lecture (and the rest of this course) will be devoted to taking that next step.

The most important thing is that your code works. Obviously. But some software is better than others. Good code creates less work for people, not more.

Good code is easy to use, easy to understand, and easy to modify.

In this lecture we will introduce the methods and tools needed to write better code.

Imagine you are reading though someone else's code and you come across this function:

def F (n):

if n==0: return 0

elif n ==1 :

return 1

else:return F(n-1)+F(n- 2)What does it do? This method has a subtle bug, can you find it?

Here is the exact same function, but following the PEP8 Style Guide:

def fibonacci(n):

""" Returns the n-th term in the Fibonacci Sequence """

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2)It has comments, so you immediately know exactly what it does. The regular 4-space tabs make it easy to compare the if-statements. And now that you fully grasped what the function does, you can start testing it with various values to see how it behaves. The bug: the method fails when passed a negative number.

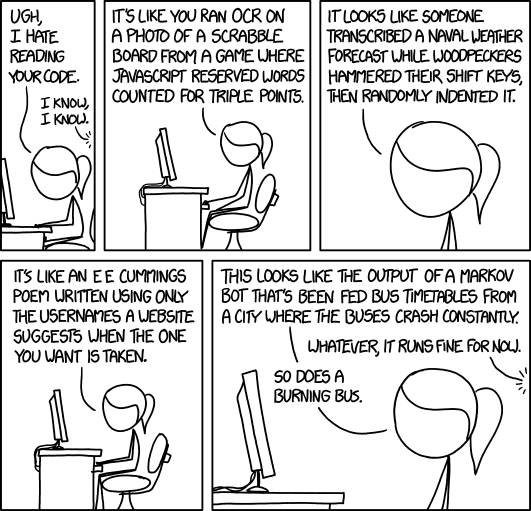

To make your code readable you have to be extremely consistent about your spaces, naming conventions, comments, etcetera. If you want to spend the time to develop all of your own conventions, and stick to them stoically, great. Good for you. The rest of the world will use the PEP8 Style Guide.

If you have a lot of code that is not PEP8-compliant, there are tools out there to automatically reformat your Python code. One of my favorites is AutoPEP8.

You are what you comment.

If someone else has to look at your code, and there are no comments, you are wasting their time. They might spend minutes or even hours trying to figure out a detail they could have understood in a split-second from a comment.

Code that isn't commented well is destined to be thrown away. But first people might get angry with you.

The PEP8 Style Guide has lots of good notes on how to comment your code.

The single-line comment is the #:

# beginning of the line comment

result = 1 # end of the line comment

for i in range(2, N+1):

result *= iBut there are also multi-line comments as we saw in the Functions and Modules lecture:

'''

This

is a

multi-line

comment

'''

"""This is also a multi-line comment.

"""There are several ways to fix any problem. But for learning purposes, let's fix the fibonacci function above by raising an Exception.

An Exception is a Python class designed to halt the current program politely when an error occurs and return a string so the user can know what the problem is. You have already seen many Exceptions in Python. Every time we make a bone-headed mistake Python returns an Error, which is just a type of Exception:

>>> 4 / 'a'

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for /: 'int' and 'str'In the case above, TypeError subclasses Error which subclasses Exception.

We could fix the fibonacci function above by adding a raising a single Exception:

def fibonacci(n):

""" Returns the n-th term in the Fibonacci Sequence """

if n < 0:

raise Exception('fibonacci only accepts non-negative inputs')

if n == 0:

return 0

elif n == 1:

return 1

else:

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2)This certainly fixes the problem. But if you call fibonacci(6), the statement if n < 0 will be called 25 times. That is a lot of extra calculation that doesn't need to be done. Another option is that you can put a try / except where you call fibonacci:

try:

fibonacci(-333)

except:

print('fibonacci only accepts non-negative inputs')Enclosing the call to fibonacci with try / except means Python will print the given line to the screen and supress all of the ugly errors you would have seen. Exceptions are an extremely powerful tool to help you control practically any unexpected behaivor in Python. Notice, we can both raise our own Exceptions, and use try/except to catch them. We will need to understand both directions to use Exceptions well.

Let's take another look at that except statement above. It is pretty vague. What if you called fibonacci('oops')? Well, that would cause an error, but your try / except block would print the wrong message. This time it would be TypeError. It would be more helpful to your user if you printed a helpful message that actually told them what the problem was. Let's show a try / except block that will catch both types of errors:

try:

fibonacci(-333)

except RuntimeError:

print('fibonacci only accepts non-negative inputs')

except TypeError:

print('fibonacci needs to be passed integer values')

except Exception as e:

print('An error occured in fibonacci: ', e)In the final except statement, we can catch any type of Exception in case something unexpected happens. In this case it is handy to print the Exception and code itself, to provide more information.

Here is a full list of Python's built-in Exceptions. I refer back to this list a lot.

One last thing we might want to do is create our own Exception. This will help us catch a specific kind of problem that we might face in our own code. For instance:

>>> class BadScienceError(Exception):

... def __init__(self, value):

... self.value = value

... def __str__(self):

... return repr(self.value)

...

>>> initial_mass = 5.213

>>> final_mass = some_projectile_motion(initial_mass, velocity)

>>> if intial_mass != final_mass:

raise BadScienceError('Initial and Final masses were not equal.')You will never need to create your own Exception. But you may find it useful, particularly in larger projects.

Be smart when choosing between functions and classes in your code.

The fibonacci function above is a good example of when to use a function. It is a small piece of code that you might want to call. It doesn't have a lot of variables that should be stored off as class attributes. It doesn't have multiple functions working together.

It is a small, self-contained piece of code that you will want to call independently from anything else.

If you have more than, say, five arguments to a function consider making it a class. So instead of having to do something like this:

def my_super_plot(x_data, y_data, x_title, y_title, x_pixels, y_pixels):

# making an amazing, beautiful plot

my_super_plot(x_data, y_data, 'Energy from atomic tests (kJ)',

'amount of U239 (kg)', 320, 480)We could do something more like this:

class MySuperPlot:

def __init__(self, x_data, y_data):

self.x_data = x_data

self.y_data = y_data

self.x_title = ''

self.y_title = ''

self.x_pixels = 640

self.y_pixels = 800

def show_plot(self):

# making an amazing, beautiful plot

plot = MySuperPlot(x_data, y_data)

plot.x_pixels = 1500

plot.y_pixels = 1000

plot.show_plot()The class version of the plot-making function is actually more code. But it will be easier to less messy and far easier to read.

Another option is to make use of Python's keyword arguments:

class MySuperPlot:

def __init__(self, x_data=None, y_data=None, x_title="Default Title",

y_title="Default Title", x_pixels=640, y_pixels=800):

self.x_data = x_data

self.y_data = y_data

self.x_title = x_title

self.y_title = y_title

self.x_pixels = x_pixels

self.y_pixels = y_pixels

def show_plot(self):

# making an amazing, beautiful plot

plot = MySuperPlot(x_data=some_thing, y_data=something_else,

x_title='Time (years)', y_title='Population')

plot.show_plot()If you ever find that you have written a script with a lot of information saved in global variables, consider using a class. If you have more than, say, five global variables in your script it might be easier to place them inside your class.

Imagine you are writing a script (glitter_gold.py) that might get used by someone else.

if __name__ == '__main__':

glitter = '''All that is gold does not glitter,

Not all those who wander are lost;

The old that is strong does not wither,

Deep roots are not reached by the frost.

From the ashes a fire shall be woken,

A light from the shadows shall spring;

Renewed shall be blade that was broken,

The crownless again shall be king.

'''

print(glitter)Now, if someone were to call this script from the command line, they would see your poem printed:

$ python glitter_gold.py

All that is gold does not glitter,

...

But what if you want to import this string from another script? Well, you can't. To help other people import and use your code, you have to make your data globally accessible in the file:

glitter = '''All that is gold does not glitter...'''

if __name__ == '__main__':

print(glitter)Now someone importing your script can do the same thing simply by typing:

import glitter_gold

print(glitter_gold.glitter)Or they could just do:

from glitter_gold import glitter

print(glitter)It works the same with functions as it does with the glitter string above. The more content you put under the if __name__ == '__main__': statement, the less will be easily available for import.

Software works best when it is shared. Software shared between multiple people, developed and improved by everyone becomes easier to understand, easier to use, easier to update, and better.

The best way to share code is via a code repository. This is a central place where we can store code, save different versions, make updates, and track changes. If you're not using a code repository, your scripts and programs are just little text files on your computer, waiting to be lost.

The two most popular code repositories are Git and SVN. Both are good and have their advantages. If you are comfortable with the command line, Git is easier to use. If you want to use your mouse, SVN is easier. If you have very small or very large projects, Git is probably the way to go.

I have already written a short introduction to Git, it is on GitHub here.

If you really want to get to know Git, try playing git-game.

As you may have already noticed, this class is being stored and displayed using GitHub, which is just a nice web interface for a Git repository.