-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1.9k

Lesson 4: Perspective projection

In previous lessons we rendered our model in orthographic projection by simply forgetting the z-coordinate. The goal for today is to learn how to draw in perspective:

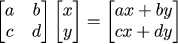

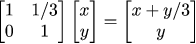

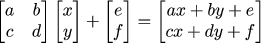

A linear transformation on a plane can be represented by a corresponding matrix. If we take a point (x,y) then its transformation can be written as follows:

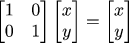

The simplest (not degenerate) transformation is the identity, it does not move any point:

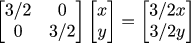

Diagonal coefficients of the matrix give scaling along coordinate axes. Let us illustrate it, if we take the following transformation:

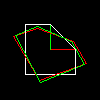

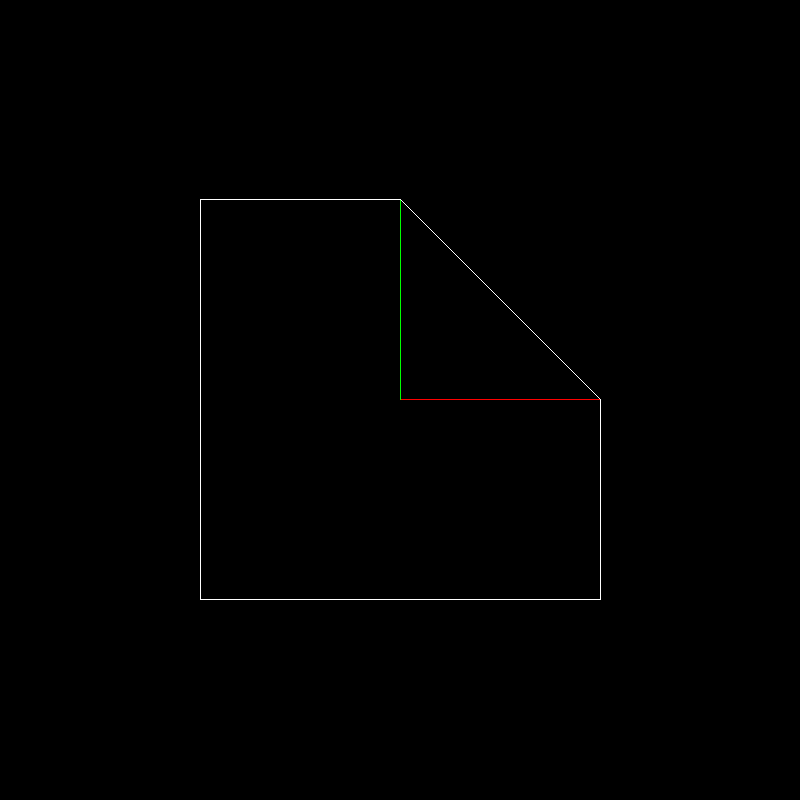

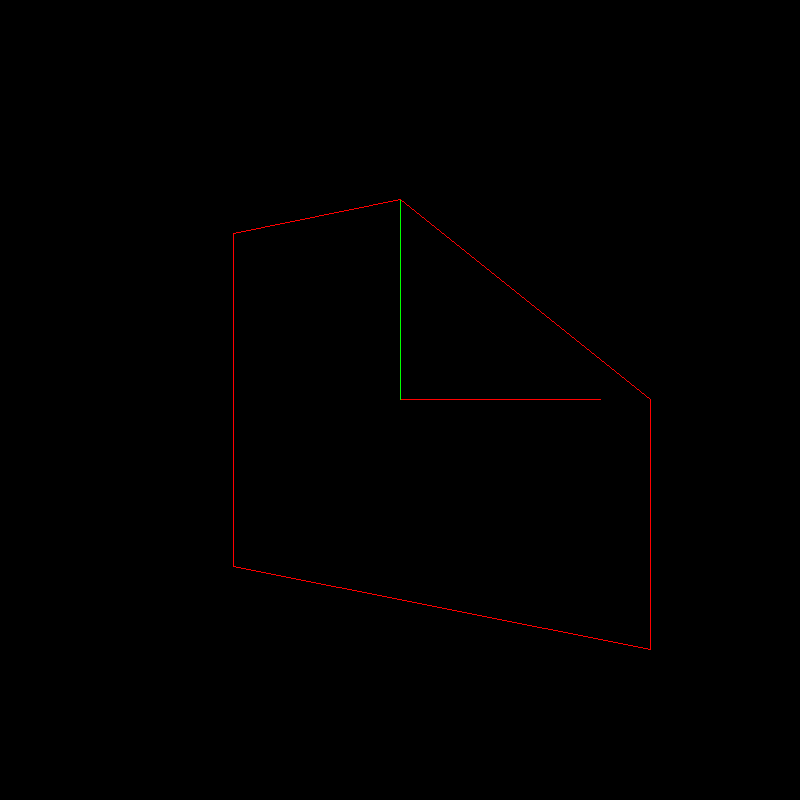

Then the white object (the white square with one corner chopped) will be transformed into the yellow one. Red and green line segments give unit length vectors aligned with x and y, respectively:

All the images for this article were generated using this code.

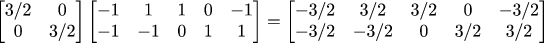

Why do we bother with matrices? Because it is handy. First of all, in matrix form we can express a transformation of the entire object like this:

In this expression the transformation matrix is the same as in the previous one, but the 2x5 matrix is nothing else but the vertices of our squarish object. We simply took all the vertices in an array, multiplied it by the transformation matrix and obtained the transformed object. Cool, is it not?

Well, the true reason hides here: very, very often we wish to transform our object with many transformations in a row. Imagine that in your source code you write transformation functions like

vec2 foo(vec2 p) return vec2(ax+by, cx+dy);

vec2 bar(vec2 p) return vec2(ex+fy, gx+hy);

[..]

for (each p in object) {

p = foo(bar(p));

}This code performs two linear transformations for each vertex of our object, and often we count those vertices in millions. And tens of transformations in a row is not a rare case, resulting in tens millions of operations, really expensive. In matrix form we can pre-multiply all the transformation matrices and to transform our object one time. For an expression with multiplications only we can put parentheses where we want, can we?

Okay, let us continue. We know that diagonal coefficients of the matrix scale our world along the coordinate axes. What other coefficients are responsible for? Let us consider the following transformation:

Here is its action on our object:

It is a simple shearing along the x-axis. Another anti-diagonal element shears our space along the y-axis. Thus, there are two base linear transformations on a plane: scaling and shearing. Many readers react: wait, what about rotations?!

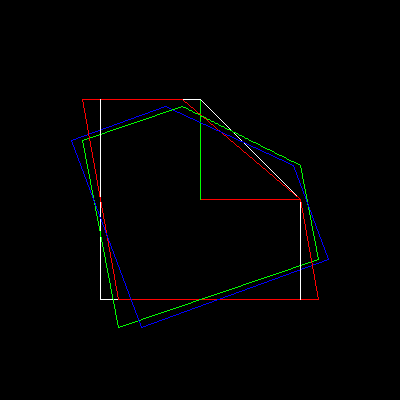

It turns out that any rotation (around the origin) can be represented as a composite action of three shears, here the white object is transformed to the red one, then to the green one and finally to the blue:

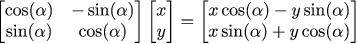

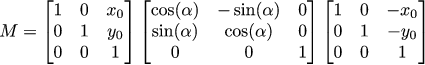

But those are intricate details, to keep the things simple, a rotation matrix can be written directly (do you remember the pre-multiplication trick?):

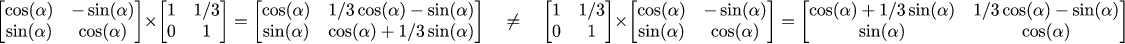

We can multiply the matrices in any order, but let us remember that the multiplication for matrices is not commutative:

It makes sense: to shear an object and then to rotate it is not the same as to rotate it and then to shear it!

So, any linear transformation on a plane is a composition of scale and shear transformations. And it means that we can do any linear transformation we want, the origin wont ever move! Those possibilities are great, but if we can not perform simple translations, our life will be miserable. Can we? Okay, translations are not linear, no problem, let us try to append translations after performing the linear part:

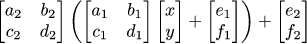

This expression is really cool. We can rotate, scale, shear, and translate. However, let us recall that we are interested in composing multiple transformations. Here is what a composition of two transformations looks like (remember, we need to compose dozens of those):

It is starting to look ugly even for a single composition, add more and things get even worse.

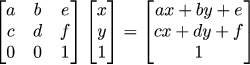

Okay, now it is the time for the black magic. Imagine that I add one column and one row to our transformation matrix (thus making it 3x3) and append one coordinate always equal to 1 to our vector to be transformed:

If we multiply this matrix and the vector augmented by 1 we get another vector with 1 in the last component, but the other two components have exactly the shape we would like! Magic.

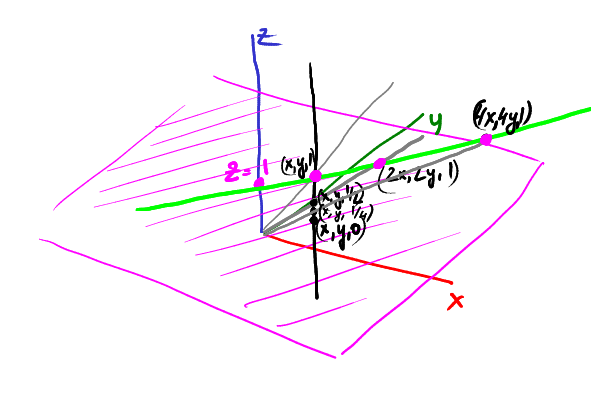

In fact, the idea is really simple. Parallel translations are not linear in the 2D space. So we embed our 2D into 3D space (by simply adding 1 for the 3rd component). It means that our 2D space is the plane z=1 in the 3D space. Then we perform a linear 3D transformation and project the result onto our 2D physical plane. Parallel translations have not become linear, but the pipeline is simple.

How do we project 3D back onto the 2D plane? Simply by dividing by the 3d component:

Who said this? [Shoots] Let us recall the pipeline:

- We embed 2D into 3D by putting it inside the plane z=1

- We do whatever we want in 3d

- For every point we want to project from 3D into 2D we draw a straight line between the origin and the point to project and then we find its intersection with the plane z=1.

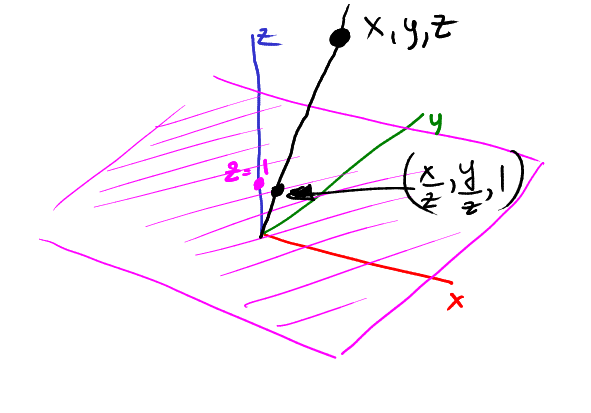

In this image our 2D plane is in magenta, the point (x,y,z) is projected onto (x/z, y/z):

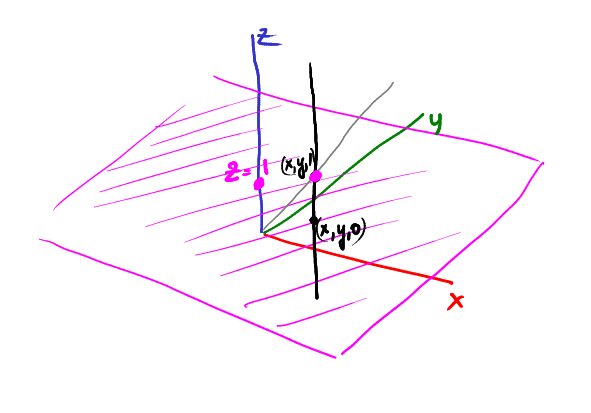

Let us imagine a vertical rail through the point (x,y,1). Where will be projected the point (x,y,1)? Doh, onto (x,y):

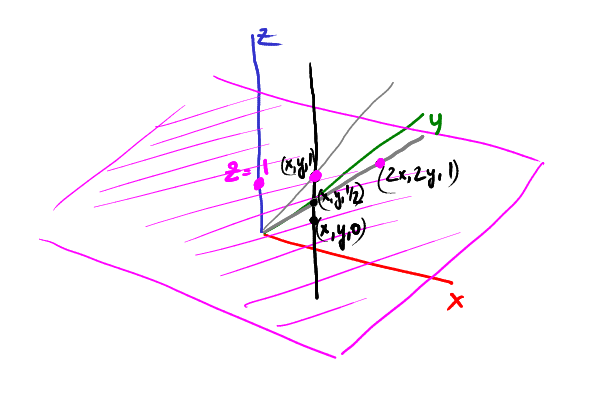

Now let us descend on the rail, for example, the point (x,y,1/2) is projected onto (2x, 2y):

Let us continue, point (x,y,1/4) becomes (4x, 4y):

If we continue the process, approaching to z=0, then the projection goes farther from the origin in the direction (x,y). In other words, point (x,y,0) is projected onto an infinitely far point in the direction (x,y). What is it? Right, it is simply a vector!

Homogeneous coordinates allow to distinguish between a vector and a point. If a programmer writes vec2(x,y), is it a vector or a point? Hard to say. In homogeneous coordinates all things with z=0 are vectors, all the rest are points. Look: vector + vector = vector. Vector - vector = vector. Point + vector = point. Great, is not it?

As i said before, we should be able to accumulate dozens of transformations. Why? Let us imagine we need to rotate an object (2D) around a point (x0,y0). How to do it? Well, we could look up for formulas somewhere, or we can do it by hand, we have all the tools we need!

We know to rotate around the origin, we know how to translate. It is all we need: translate (x0,y0) into the origin, rotate, un-translate, done:

In 3D sequences of actions will be a bit longer, but the idea is the same: we need to know few basic transformations and with their aid we can represent any composed action.

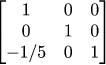

Sure thing! Let us apply the following transformation to our standard squarish object:

Recall that the original object is in white, unit axis vectors are in red and green:

Here is the transformed object:

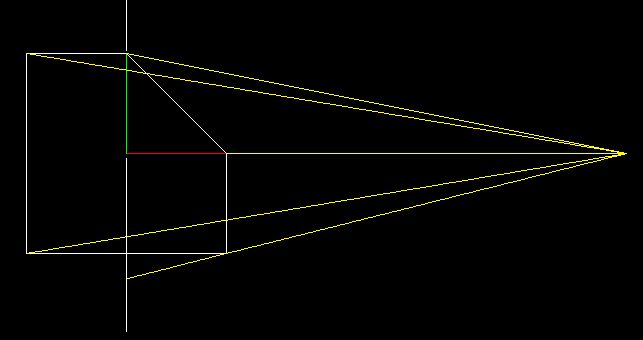

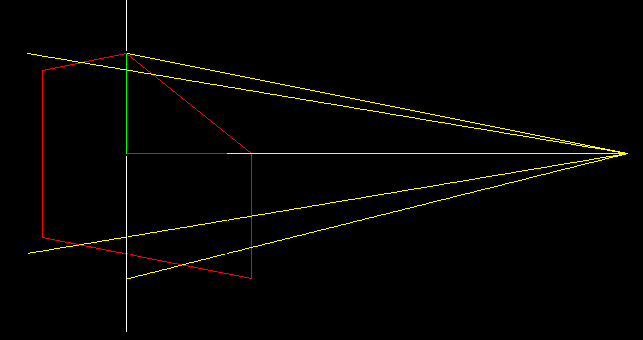

And here another kind of magic (white!) happens. Do you remember our y-buffer exercise? Here we will do the same: we project our 2D object onto the vertical line x=0. Let us harden the rules a bit: we have to use a central projection, our camera is in the point (5,0) and is pointed onto the origin. To find the projection we need to trace straight lines between the camera and the points to be projected (yellow) and to find the intersection with the screen line (white vertical).

Now i replace the original object with the transformed one, but i do not touch the yellow lines we drew before:

If we project the red object onto the screen using standard orthogonal projection, then we find exactly the same points! Let us look closely how the transformation works: all vertical segments are transformed into vertical segments, but those close to the camera are stretched and those far from the camera are shrunk. If we choose the coefficient correctly (in our transformation matrix it is the -1/5 coefficient), we obtain an image in perspective (central) projection!

Let us explain the magic. As for 2D affine transformations, for 3D affine transformations we will use homogeneous coordinates: a point (x,y,z) is augmented with 1 (x,y,z,1), then we transform it in 4D and project back to 3D. For example, if we take the following transformation:

The retro-projection gives us the following 3D coordinages:

Let us remember this result, but put it aside for a while. Let us return to the standard definition of the central projection, without any fancy stuff as 4D transformations. Given a point P=(x,y,z) we want to project it onto the plane z=0, the camera is on the z-axis in the point (0,0,c):

Triangles ABC and ODC are similar. It means that we can write the following: |AB|/|AC|=|OD|/|OC| => x/(c-z) = x'/c. In other words:

By doing the same reasoning for triangles CPB and CP'D, it is easy to find the following expression:

It is really similar to the result we put aside few moments ago, but there we got the result by a single matrix multiplication. We got the law for the coefficient: r = -1/c.

If you simply copy-paste this formula without understanding the above material, I hate you.

So, if we want to compute a central projection with a camera (important!) camera located on the z-axis with distance c from the origin, then we embed the point into 4D by augmenting it with 1, then we multiply it with the following matrix, and retro-project it into 3D.

We deformed our object in a way, that simply forgetting its z-coordinate we will get a drawing in a perspective. If we want to use the z-buffer, then, naturally, do not forget the z. The code is available here, its result is visible in the very beginning of the article.

A quick fix for the compiling error (C++ 14/17) of the code above:

In geometry.cpp, changing from:

template <> template <> Vec3<int>::Vec3<>(const Vec3<float> &v) : x(int(v.x+.5)), y(int(v.y+.5)), z(int(v.z+.5)) {}

template <> template <> Vec3<float>::Vec3<>(const Vec3<int> &v) : x(v.x), y(v.y), z(v.z) {}

To:

template <> template <> Vec3<int>::Vec3(const Vec3<float>& v) : x(int(v.x + .5)), y(int(v.y + .5)), z(int(v.z + .5)) {}

template <> template <> Vec3<float>::Vec3(const Vec3<int>& v) : x(v.x), y(v.y), z(v.z) {}