- Universal Basic Income Currency

- Previous work and other projects

- Economics

- Sybil Resistance

- Consensus

- The E-Passport

- Proof of Signature Knowledge

- Address structure

- Transactions

- Blocks

- Possible issues

- Other applications

In current cryptocurrency schemes, rewards are distributed to entities that secure the network through Proof of Work or Proof of Stake mechanisms. There are no rewards for being part of the network. Because current reward mechanisms always result in a very asymmetric value distribution between participants, UBIC proposes a monetary system where all participants are rewarded through a universal basic income.

As of 2020, thousands of cryptocurrencies exist and UBIC is not the first project aiming to implement a UBI distribution. The main difference between non-UBI and UBI cryptocurrencies is the need to solve the Sybil attack.

Some projects like "Duniter" for example have created a Web of Trust (WOT) that requires users to "verify" each other. While the idea is simple, actually building a secure Web of Trust is complex and requires advanced graph theory algorithms and manual verification. Another approach, which can be seen through puzzle-solving with “Idena” is a Turing-Test for participants. This type of test consumes a lot of time for willing participants and resistance against artificial intelligence remains a continuous challenge.

UBIC attempts to solve this issue through a new approach, where the innovation gap is much lower, by using existing digital features offered by modern passports.

A currency with unlimited supply is likely to have little to no value. This is why the total supply should be capped to a fixed amount every year. While there will be different currencies running on one unique blockchain, each currency will be associated with one country. They will be identified by U + the iso2 country code.

For example, ‘UCH’ will be the currency for Switzerland, ‘UDE’ for Germany, ‘UAT’ for Austria, and ‘UUK’ for the UK.

A large share of the supply will be equally distributed among addresses that were successfully associated with a passport. What this means is that if the block supply for UCH, the Swiss UBIC currency, is 100 units per block and there are 50 registered passports, each will get 2 units per block. Some weeks later, when there are 500 registered passports and the reward is still 100 units per block, every passport holder will get 0.2 units per block.

The table below shows the distribution rates for each UBIC currency.

| Currency code | Country | UBI yearly emission rate | additional information |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCH | Switzerland | 10,196,640 | |

| UDE | Germany | 100,599,840 | |

| UAT | Austria | 10,617,120 | passports after October 2014 |

| UUK | United Kingdom | 79,838,640 | |

| UIE | Ireland | 5,781,600 | passports after May 2016 |

| UUS | USA | 393,096,240 | |

| UAU | Australia | 29,223,360 | |

| UCN | China | 1,677,767,760 | Hong Kong passports after July 2019 |

| USE | Sweden | 12,036,240 | |

| UFR | France | 81,730,800 | |

| UCA | Canada | 44,150,400 | |

| UJP | Japan | 154,526,400 | passports after May 2016 |

| UTH | Thailand | 81,520,560 | |

| UNZ | New Zealand | 5,571,360 | |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates | 11,300,400 | |

| UFI | Finland | 6,675,120 | |

| ULU | Luxemburg | 525,600 | |

| USG | Singapore | 6,832,800 | |

| UHU | Hungary | 11,931,120 | |

| UCZ | Czech Republic | 12,877,200 | |

| UMY | Malaysia | 38,684,160 | |

| UUA | Ukraine | 54,767,520 | |

| USP | Spain | 108,000,000 | passports after July 2016 |

| UIS | Iceland | 420,480 | passports after February 2013 |

| UEE | Estonia | 1,681,920 | No registration possible yet |

| UMC | Monaco | 52,560 | No registration possible yet |

| ULI | Liechtenstein | 52,560 | No registration possible yet |

| UIS | Iceland | 420,480 | passports after february 2013 |

| UHK | Hong Kong | 8,988,000 | No registration possible yet |

| UES | Spain | 56,764,800 | passports after July 2016 |

| URU | Russia | 176,202,144 | |

| UIL | Israel | 10,833,078 | |

| UPT | Portugal | 12,535,349 | |

| UDK | Denmark | 7,079,789 | |

| UTR | Turkey | 99,990,144 | |

| URO | Romania | 23,668,398 | |

| UPL | Poland | 46,300,314 | |

| UNL | Netherlands | 21,071,093 |

*The numbers displayed are maximum numbers, assuming that one block is minted every minute

In addition to the distribution above, 10% of coins are minted by the validator nodes. The dev fund also collects an additional reward of 10%, which halves every 525,600 blocks, until it reaches 1.25%

UBICs ability to resist Sybil attacks is based on the security features of modern E-Passports. You can join by scanning your E-Passport via NFC. Your identity will NOT be revealed, thanks to a Proof of Signature Knowledge. Instead, there is only a unique hash of your passport stored on the blockchain. More detail on this will be explained later.

UBIC is currently restricted for use in 28 countries which fulfill all security requirements for UBIC to work Sybil-proof. More participants may be able to join when their country follows more secure technical procedures regarding their E-Passports.

Electronic passports, sometimes known as biometric passports, have already been introduced in many countries through the last decade. These passports provide additional security through NFC and Cryptographic technologies, making forgery virtually impossible. The E-Passport is standardized by the DOC9303 paper from the ICAO, therefore all E-passports have to implement a set of required features. There is a bit of freedom regarding the cryptographic algorithms used, and some are not safe enough for UBIC yet. For example, Hong Kong used a 3 as their RSA exponent until June 2019, while UBIC requires a much bigger RSA exponent of 65537 or more. This is why all passports cannot be used with UBIC.

The key part of the E-Passport is the NFC chip that is embedded in it. This chip contains 32kb to 64kb of information distributed in several Data Groups:

- Data Group 1 contains the Machine Readable Zone also known as MRZ, it includes information such as the first name, last name, date of birth, and the date of expiration.

- Data Group 2 contains the facial image.

- Data Group 3 contains the fingerprints. This group can only be accessed using the Extended Access Control, which is only available to governments.

Finally, the Document Security Object is a PKCS7 file that contains the hash of all the different Data Groups. This file is signed using a Document Signing Certificate issued by a government. In the case of UBIC, only the Document Security Objects will be read out to generate a Proof of Signature Knowledge.

Using NFC technology, it is possible to read out passive tags that are up to 10cm away. Theoretically, it would be possible to read out a passport through someone’s pocket, however, this isn't easy because of a security feature known as the Basic Access Control. If enabled, the passport number, date of birth, and date of expiry act as a password, and must be provided for the chip to read out the content.

As described by DOC9303, the Document Signing Certificates are issued at least once every three months and have a limited signing period, after which the private key should be destroyed. This ensures that if one DSC is misused, only a limited set of passports must be reissued. All DSCs have to be signed by a Country Signing Certificate Authority (CSCA).

The Country Signing Certificates are issued by the CSCA. This entity has the highest level of privilege within the governmental Public Key Infrastructure.

The Public Key Directory is a service that provides the Country Signing and Document Signing Certificates. The link to download them is: https://pkddownloadsg.icao.int/ The PKD is not the only source to get those certificates, as some governments publish their Country Signing Certificate, and the ones of other countries they trust, online. DSCs can also be found on passports themselves.

The Proof of Signature Knowledge is the key element that allows UBIC to operate. It does so by providing a way to decently and securely verify that there is a link between a UBIC address and an unknown but genuine passport. The Proof of Signature Knowledge proves the knowledge of a digital signature without revealing it.

Let's be  the hash of the passport information,

the hash of the passport information,  the elliptic curve point extracted from the signature

the elliptic curve point extracted from the signature  On the blockchain will be revealed:

On the blockchain will be revealed:

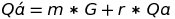

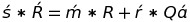

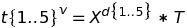

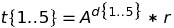

Let's be  the hash of the passport information,

the hash of the passport information,  the RSA exponent typically

the RSA exponent typically  and

and  the signature then the solution to prove knowledge of A according to the Guillou-Quisquater protocol is to reveal:

the signature then the solution to prove knowledge of A according to the Guillou-Quisquater protocol is to reveal:

the RSA exponent typically

the RSA exponent typically

the hash of the passport information

the hash of the passport information where d is a 16 bit salted hash derivated from the UBIC public key and r is a cryptographicaly secure random number

where d is a 16 bit salted hash derivated from the UBIC public key and r is a cryptographicaly secure random number such than

such than

Because 1 < d < e and e usually equals to  the operation above has to be done several times with different values of d, in fact at least 5 times in the current UBIC implementation.

the operation above has to be done several times with different values of d, in fact at least 5 times in the current UBIC implementation.

The operation above has to be repeated for each value of d generated during the proof generation.

An address is a base58 binary and is structured as follows:

<program identifier> <payload length> <payload> <checksum>

1 byte 1-4 bytes x bytes 3 bytes

The program identifier allows UBIC to easily evolve and add new functionalities such as a new Script language for smart contracts.

Example:

<program identifier> <payload length> <payload> <checksum>

0x02 0x14 0x23be5a8564ebc151004d798ef812aa25ee7ff79 0x23f234

0x02 is the program identifier for pay to hash using ripemd160((sha256(public key)) as hashing.

0x14 is the the hexadecimal representation of 20 which is the length of the ripemd160 hash.

0x23be5a8564ebc151004d798ef812aa25ee7ff79 is the payload. In this case the hash of the public key.

0x23f234 is the checksum that is obtained by taking the leading 3 bytes from the result of sha256(<program identifier> <payload length> <payload>)

There is no need to have one address for every currency. One single address can receive, hold, and send all UBIC currencies.

Transactions can have one or more inputs and zero, one, or more outputs. The input values always have to be greater than or equal to the output values. The difference between sum(inputs) - sum(outputs) are the transaction fees that are burned, which is meant to reduce inflation. A transaction can transfer several currencies at one time, however, it is not possible to transform one currency to another.

The standard transaction's structure is as follows:

- network

- txIns

- amount

- inAddress

- nonce

- script

- txOuts

- amount

- script

The network is an uint8_t field, it ensures that a transaction from the test network cannot be broadcasted on the main one.

The nonce is an uint32_t field, it ensures that a transaction cannot be replayed multiple times.

The amount field is a map that maps a currency id (uint8_t) to a currency amount (uint64_t).

The script field is a std::vector<unsigned char> field that is intended to contain a serialized object.

In a scenario where Alice holds 10 UCH and wants to exchange them for 10 UDE from Bob, a transaction could be built for this purpose. Let’s 0x17a6 be Alice's address and 0x98b1 Bob's address. Then the transaction having as inputs 0x17a6(10 UCH), 0x98b1(10 UDE) and as outputs 0x17a6(10 UDE), 0x98b1(10 UCH) would serve this purpose.

Blocks are structured the as follows:

- BlockHeader

- version

- headerHash

- previousHeaderHash

- merkleRootHash

- blockHeight

- timestamp

- payout

- payoutRemainder

- ubiReceiverCount

- votes

- issuerPubKey

- issuerSignature

- Transactions

With UBIC there are no miners. Instead, blocks are validated by delegates. The genesis contains 8 centrally controlled delegates that will support the network in its early stage. As time goes by, new delegates will be added and the genesis delegates will be removed, making UBIC truly decentralized. The addition and removal of delegates is regulated by a voting mechanism in which only delegates are allowed to vote. Delegates can be people, companies, nonprofit organizations, or any entity capable of running a node and willing to support this project. Delegates will be designated by the community and later be voted by the other delegates. Should a delegate misbehave other delegates are encouraged to revoke their privilege by doing an unvote.

For privacy reasons, no personal information is transmitted to the blockchain. UBIC assumes that every individual has only one valid passport but this might not be true. People can get a new passport before the old one is expired or claim that it has been stolen. Because passport revocation lists are not public, UBIC assumes that every passport that hasn't reached the date of expiry is valid. It could be that some individuals end up with 2 or 3 verified addresses but it is unlikely they'll get more because some factors mitigate this risk:

- Genuine passports are worth several thousand dollars on the black market. This is why people who "lose" their passport too often are barred from getting a new one, and draw attention from law enforcement.

- The fees and the time that is required to get a new passport might outweigh the benefit of receiving additional UBI.

- Governments could issue passport revocation lists. A stolen or lost passport will immediately stop receiving additional coins.

Some governments might be hostile to the idea of cryptocurrency. They could then try to harm its growth through legislation or hacking. Because governments are responsible for emitting the Document Signing Certificates, they could spam the network with passport registration transactions. This appears to be unlikely, however, as it will certainly lower their credibility and damage them.

While it is difficult for a non-institutional participant to link an address to an identity, governments that emitted the passport certainly will be able to do so.

Although there is no personal information stored on the blockchain itself, a user could decide to reveal the information contained in the Data Group 1 and/or Data Group 2 to another entity.

Two voting schemes are possible with UBIC. In the first, voting is weighted by the currency holdings of the voters, as it is already done with many cryptocurrencies. In the second scheme, only the UBI receiver can vote, with each carrying a voting weight of 1. This is possible because the country of origin from the voter is known, so votes can also be country-specific.