A modern, object-oriented JSON-RPC 2.0 server for PHP 8.0+ featuring JSON Schema integration and middlewaring.

$ composer require uma/json-rpcSetting up a JsonRpc\Server involves three separate steps: coding the procedures you need,

registering them as services and finally configuring and running the server.

Procedures are akin to HTTP controllers in the MVC pattern, and must implement the UMA\JsonRpc\Procedure interface.

This example shows a possible implementation of the subtract procedure found in the JSON-RPC 2.0 specification examples:

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace Demo;

use stdClass;

use UMA\JsonRpc;

class Subtractor implements JsonRpc\Procedure

{

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public function __invoke(JsonRpc\Request $request): JsonRpc\Response

{

$params = $request->params();

if ($params instanceof stdClass) {

$minuend = $params->minuend;

$subtrahend = $params->subtrahend;

} else {

[$minuend, $subtrahend] = $params;

}

return new JsonRpc\Success($request->id(), $minuend - $subtrahend);

}

/**

* {@inheritdoc}

*/

public function getSpec(): ?stdClass

{

return \json_decode(<<<'JSON'

{

"$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft-07/schema#",

"type": ["array", "object"],

"minItems": 2,

"maxItems": 2,

"items": { "type": "integer" },

"required": ["minuend", "subtrahend"],

"additionalProperties": false,

"properties": {

"minuend": { "type": "integer" },

"subtrahend": { "type": "integer" }

}

}

JSON

);

}

}The logic assumes that $request->params() is either an array of two integers,

or an stdClass with a minuend and subtrahend attributes that are both integers.

This is perfectly safe because the Server matches the JSON schema defined above against

$request->params() before even calling __invoke(). Whenever the input does not conform

to the spec, a -32602 (Invalid params) error is returned and the procedure does not run.

The next step is defining the procedures in a PSR-11 compatible container and configuring

the server. In this example I used uma/dic:

declare(strict_types=1);

use Demo\Subtractor;

use UMA\DIC\Container;

use UMA\JsonRpc\Server;

$c = new Container();

$c->set(Subtractor::class, function(): Subtractor {

return new Subtractor();

});

$c->set(Server::class, function(Container $c): Server {

$server = new Server($c);

$server->set('subtract', Subtractor::class);

return $server;

});At this point we have a JSON-RPC server with one single method (subtract) that is

mapped to the Subtractor::class service. Moreover, the procedure definition is lazy,

so Subtractor won't be actually instantiated unless subtract is actually called in the server.

Arguably this is not very important in this example. But it'd be with tens of procedure definitions, each with their own dependency tree.

Once set up, the same server can be run any number of times, and it will handle most errors defined in the JSON-RPC spec on behalf of the user of the library:

declare(strict_types=1);

use UMA\JsonRpc\Server;

$server = $c->get(Server::class);

// RPC call with positional parameters

$response = $server->run('{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"subtract","params":[2,3],"id":1}');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","result":-1,"id":1}'

// RPC call with named parameters

$response = $server->run('{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"subtract","params":{"minuend":2,"subtrahend":3},"id":1}');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","result":-1,"id":1}'

// Notification (request with no id)

$response = $server->run('{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"subtract","params":[2,3]}');

// $response is NULL

// RPC call with invalid params

$response = $server->run('{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"subtract","params":{"foo":"bar"},"id":1}');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","error":{"code":-32602,"message":"Invalid params"},"id":1}'

// RPC call with invalid JSON

$response = $server->run('invalid input {?<derp');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","error":{"code":-32700,"message":"Parse error"},"id":null}'

// RPC call on non-existent method

$response = $server->run('{"jsonrpc":"2.0","method":"add","params":[2,3],"id":1}');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","error":{"code":-32601,"message":"Method not found"},"id":1}'Since version 4.0.0 you can override the Opis Validator through the container. This allows you to use custom Opis filters, formats and media types.

To do that simply define an Opis\JsonSchema\Validator::class service in the PSR-11 container

and set it to a custom instance of the Validator class.

The following example defines a new "prime" format for integers that you can then use in your json schemas. (PrimeNumberFormat implementation is omitted for brevity):

$validator = new Opis\JsonSchema\Validator();

$formats = $validator->parser()->getFormatResolver();

$formats->register('integer', 'prime', new PrimeNumberFormat());

$psr11Container->set(Opis\JsonSchema\Validator::class, $validator);

$jsonServer = new UMA\JsonRpc\Server($psr11Container);

// ...A middleware is a class implementing the UMA\JsonRPC\Middleware interface, whose only method accepts an UMA\JsonRPC\Request,

an UMA\JsonRPC\Procedure and returns a UMA\JsonRPC\Response. At some point within its body, this method MUST call $next($request),

otherwise the request won't reach the successive middlewares nor the final procedure. Middlewares are the preferred

option whenever you need to run a chunk of code right before or after every request, regardless of the method.

Here's the minimal skeleton of a middleware:

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace Demo;

use UMA\JsonRpc;

class SampleMiddleware implements JsonRpc\Middleware

{

public function __invoke(JsonRpc\Request $request, JsonRPC\Procedure $next): JsonRpc\Response

{

// Code run before procedure

$response = $next($request);

// Code run after procedure finished

return $response;

}

}In order to activate a middleware you need to register it as a service in the dependency injection container, just like procedures.

declare(strict_types=1);

use Demo\SampleMiddleware;

use UMA\DIC\Container;

use UMA\JsonRpc\Server;

$c = new Container();

$c->set(SampleMiddleware::class, function(): SampleMiddleware {

return new SampleMiddleware();

});

$c->set(Server::class, function(Container $c): Server {

$server = new Server($c);

// method definitions would go here...

$server->attach(SampleMiddleware::class);

return $server;

});Whenever the flow of execution enters the __invoke method of a user-defined middleware, the following can be assumed

about the request:

-

The original payload was a valid JSON-RPC 2.0 request.

-

Its

methodattribute points to a procedure that is actually registered in the server. -

Its

paramsattribute conforms to the Json Schema defined in thegetSchema()of said procedure.

In short, they are the same guarantees that can be made inside the procedure.

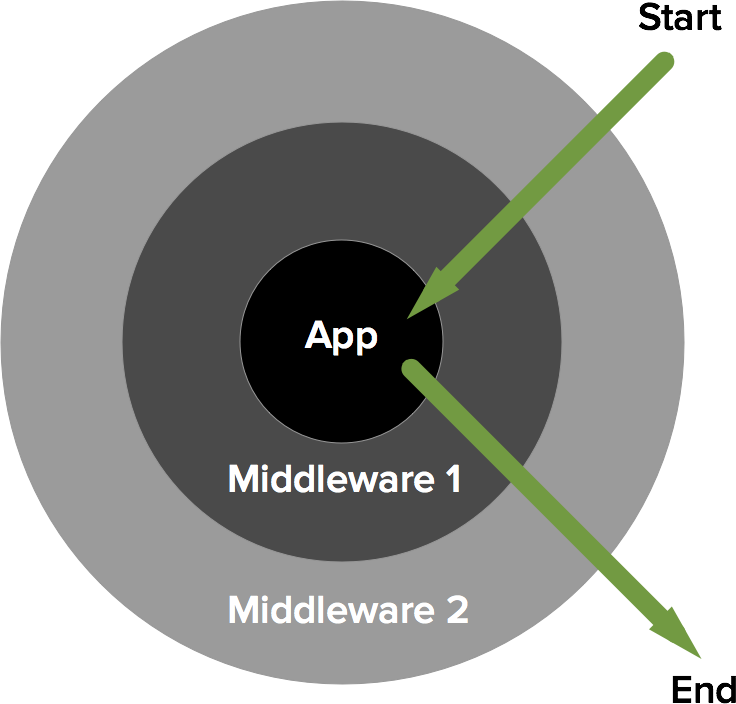

In a way, middlewares can be thought of as decorators of the Server, each one wrapping it in a new layer.

Hence, the last attached layer will be the first to run (and the last, when exiting out of the procedure).

The Slim framework documentation depicts their own middlewaring system with the following image. The same

principle applies to uma\json-rpc.

Suppose you wanted to enqueue incoming notifications to a Beanstalk tube and execute these out of the HTTP context in a separate process. Recall that a notification is a JSON-RPC request with no ID attribute. According to the JSON-RPC 2.0 spec, when a server receives one of these it has to run the method normally, but not return any output.

Instead of placing that logic at the beginning of every procedure or in an awkward base class

you can use a middleware similar to this, leveraging the fact that Request objects can be json-encoded back

to the original payload:

declare(strict_types=1);

namespace Demo;

use Pheanstalk\Pheanstalk;

use UMA\JsonRpc;

/**

* A middleware that enqueues all incoming notifications to a Beanstalkd tube,

* thus avoiding their execution overhead.

*/

class AsyncNotificationsMiddleware implements JsonRpc\Middleware

{

/**

* @var Pheanstalk

*/

private $producer;

public function __construct(Pheanstalk $producer)

{

$this->producer = $producer;

}

public function __invoke(JsonRpc\Request $request, JsonRPC\Procedure $next): JsonRpc\Response

{

if (null === $request->id()) {

$this->producer->put(\json_encode($request));

return new JsonRpc\Success(null);

}

return $next($request);

}

}Yes, some! The most significant is that the spec is built on top of JSON and nothing else (i.e. there

is no talk of HTTP verbs, headers or authentication schemes in it). As a result, JSON-RPC 2.0

is completely decoupled from the transport layer, it can run over HTTP, WebSockets, a console REPL or even

over avian carriers or sheets of paper. This is actually the reason why the interface of Server::run() works

with plain strings.

Additionally, the spec is short and unambiguous and supports "fire and forget" calls and batch processing.

I made the conscious decision of not including this feature, because it increased the complexity of the Server a lot. Therefore middlewares are always run for all requests.

However, as the user you can manually skip them when the method is not the one you want:

use UMA\JsonRpc;

class PickyMiddleware implements JsonRpc\Middleware

{

/**

* @var string[]

*/

private $targetMethods;

public function __construct(array $targetMethods)

{

$this->targetMethods = $targetMethods;

}

public function __invoke(JsonRpc\Request $request, JsonRPC\Procedure $next): JsonRpc\Response

{

if (!in_array($request->method(), $this->targetMethods)) {

return $next($request);

}

// Actual logic goes here

}

}I'm preparing a repo with a handful of examples. It will cover JSON-RPC 2.0 over HTTP, TCP, WebSockets and the command-line interface.

While it is not mandatory to return a JSON Schema from your procedures it is highly recommended to do so, because then your procedures can assume that the input parameters it receives are valid, and this simplifies their logic a great deal.

If you are not familiar with JSON Schemas there's a very good introduction at Understanding JSON Schema.

Since PHP is a language that does not have "mainstream" support for concurrent programming, whenever the server receives a batch request it has to process every sub-request sequentially, and this can add up the total response time.

Hence, a JSON-RPC server served over HTTP should strive to defer any actual work by

relying, for instance, on a work queue such as Beanstalkd or RabbitMQ. A second, out-of-band

JSON-RPC server could then consume the queue and do the actual work.

The protocol actually supports this use case: whenever an incoming request does not have an id,

the server must not send the response back (these kind of requests are called Notifications in the spec).

When a Server is exposed over HTTP, batch requests are a denial of service vector (even if PHP was capable of processing them concurrently).

A malicious client can potentially send a batch request with thousands of sub-requests, effectively clogging the resources of the server.

To minimize that risk, Server has an optional batchLimit parameter that specifies the maximum number of

batch requests that the server can handle. Setting it to 1 effectively disables batch processing, if you don't

need that feature.

PS. An attacker could also send hundreds or thousands of single requests, clogging the server all the same. But given that these are all individual HTTP requests they can be rate-limited at the webserver level.

$server = new \UMA\JsonRpc\Server($container, 2);

$server->set('add', Adder::class);

$response = $server->run('[

{"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "add", "params": [], "id": 1},

{"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "add", "params": [1,2], "id": 2},

{"jsonrpc": "2.0", "method": "add", "params": [1,2,3,4], "id": 3}

]');

// $response is '{"jsonrpc":"2.0","error":{"code":-32000,"message":"Too many batch requests sent to server","data":{"limit":2}},"id":null}'