Reads in an undirected graph with no multiple edges between any vertices. Calculates the minimum number of vertices you need to cover every edge with at least one vertex. (Vertex cover problem)

We use two packages core and vertex cover. We split the classes based on wether they have functionality for graphs themselves or for the vertex cover problem.

vertex cover consists of two packages, advanced for the actual calculations and Application for text-formatting and using it on real graphs.

By now it contains many parts that don't speed up calculation on small inputs noticably. On very big instances though, they are worth it.

For example the split into disjoint subGraphs actually slows the program down in most cases. But if you hit one big graph that can be split into disjoint subGraphs, the speedup may be 50-fold or more.

And as we're mostly optimizing for the worst case anyway, we're willing to take that drawback.

- Creating the method removeClique, which removes cliques of any size

nwhen less thannvertices are connected outside of the clique. - Applying as many rules as you can on the graph before you try to solve for

k, so you only have to apply them once (doesn't work for the high-degree rule though, as it depends on the valuekof an instance. But all other rules are applicable, you just have to track the change, we chose to use an instance for that). - Using the datastructures Hashmap and Hashset.

For representing the graph, we decided to use a HashMap that maps from integer to a HashSet of integers.

This means: The key is the ID of a vertex and the value (the set) are its neighbours.

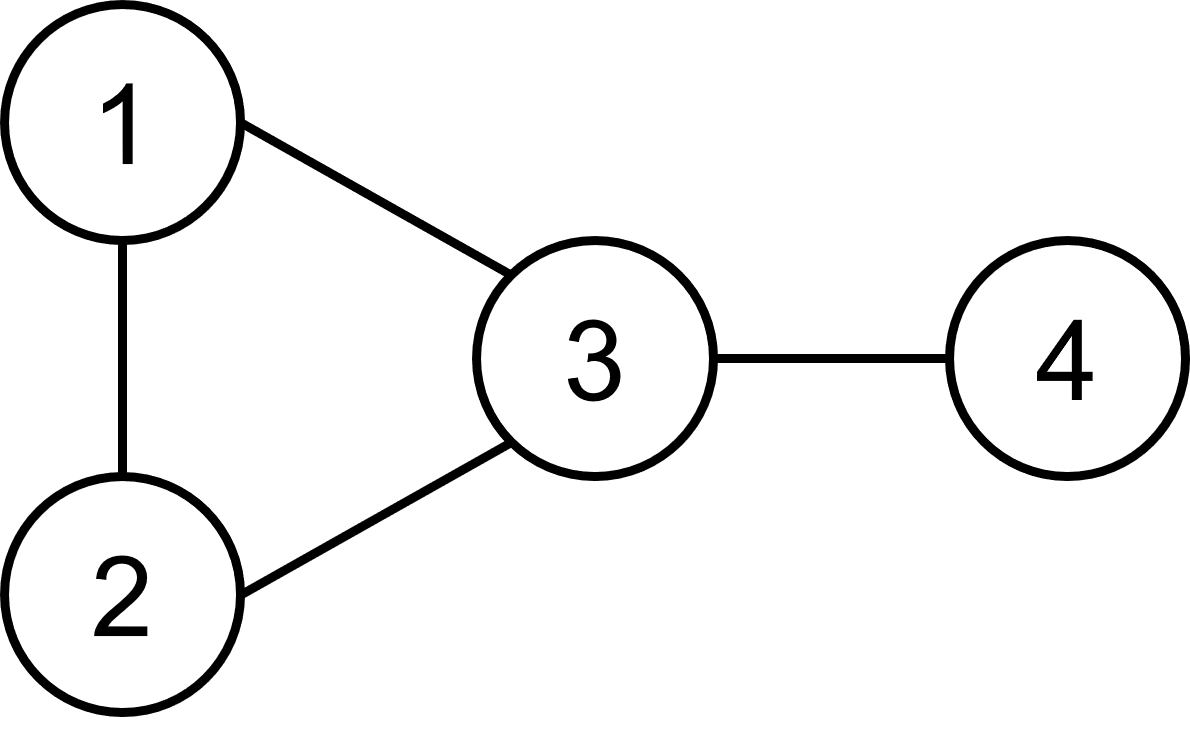

As an example here is the map for the following graph:

- 1 → {2,3}

- 2 → {3,1}

- 3 → {2,4,1}

- 4 → {3}

- This method uses less space than any solution with a matrix (unless the graph contains near the maximum amount of edges).

- It also has reasonably low runtime (the runtime is mostly dependent on the logic of the searchtree anyway).

- Also, we do less erros, because we don't have to manage any indexes of a list if we use a set.

- One class-field is sufficient for all operations we want to perform. (No synchronization is needed.)

The reduction rules are all applied exhaustively, meaning they are repeated as long as they change the graph.

For this reason their implementations all return a boolean which indicates wether a change has been made to the graph/instance. The rules are applied until every method returns false, then we break.

We always have to apply all rules, because one rule may create an opportunity for another rule to be used. As we can't really anticipate these side-effects (yet?), we always have to apply all of them.

A clique is a set of vertices which are all interconnected.

For example: a single point, two connected vertices or a triangle are examples of a clique.

If we find a clique of size n and less than n vertices are connected to a vertex outside of the clique, we can remove the clique and reduce k by n-1.

This is a generalization of the "singleton" and "degree-one" rule ⇒ It also works on arbitrarily big cliques.

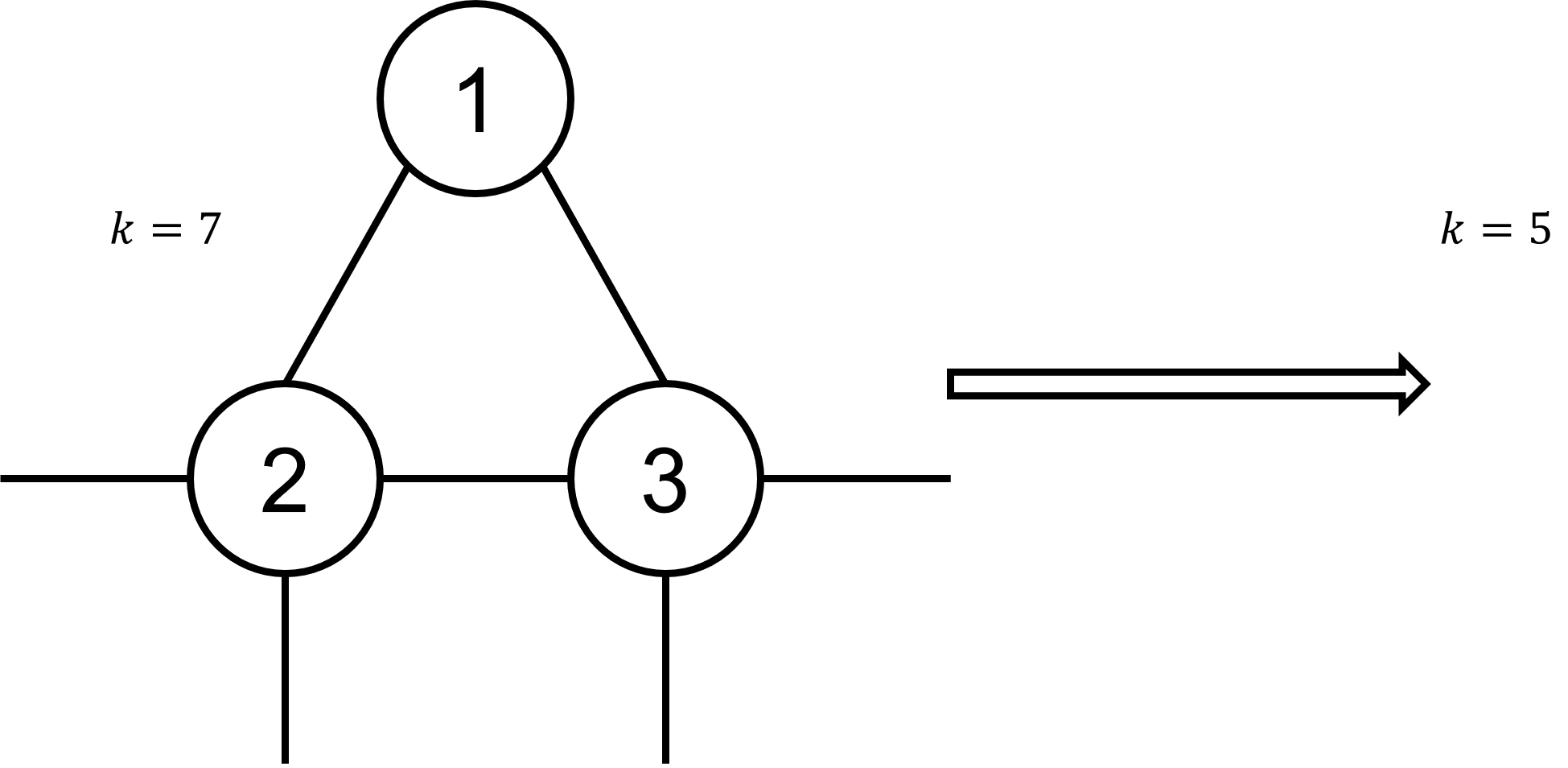

Example:

The vertices 1, 2 and 3 have edges between each other and only 2 and 3 have even more neighbours. All vertices in this triangle where deleted and k decreased by 2 (number of neighbours of 1).

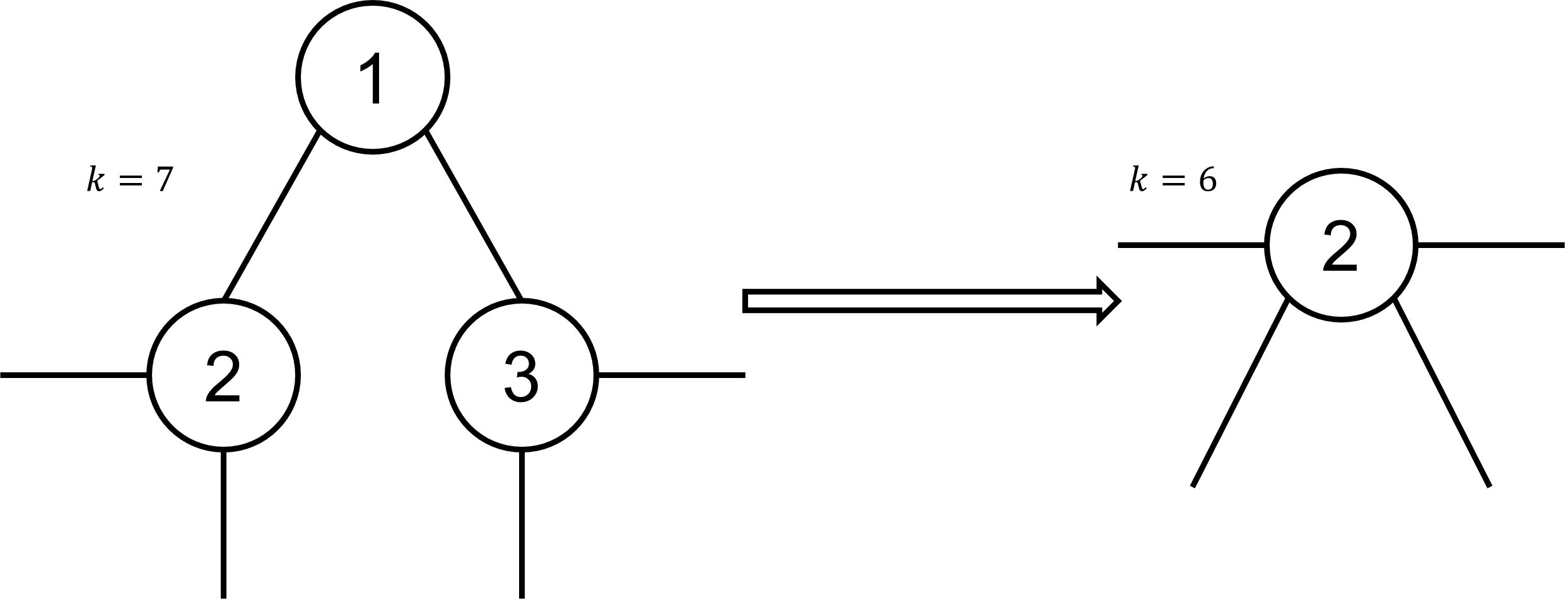

If a vertex key is only connected to two neighbours nb1 and nb2, who are themselves not neighbours of each other, we can remove key, and merge both neighbours together, which means deleting one of them and moving the connections of the

deleted one onto the remaining one.

This is done in the method mergeVertices. The direction of the merge doesn't really affect the runtime from our experience.

Example:

The vertices 2 and 3 aren't neighbours so one of them (in this example 3) was deleted and their neighbours merged.

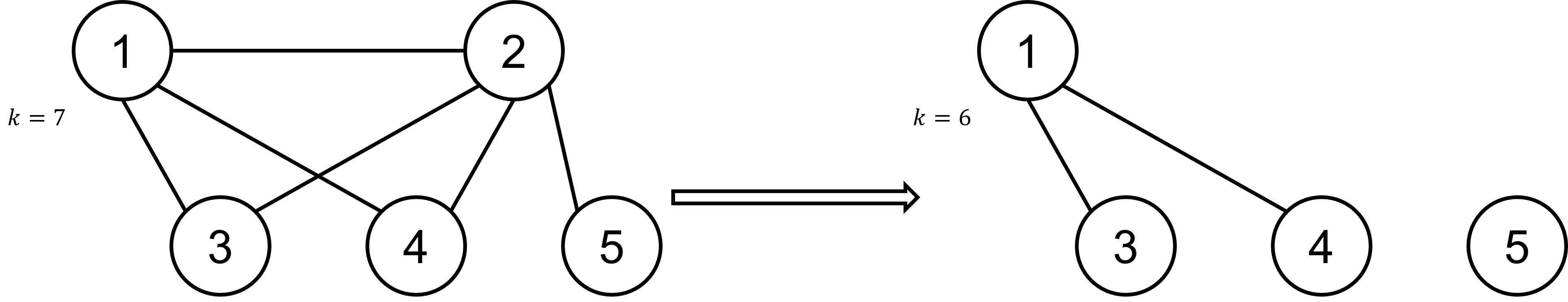

If there are two adjacent vertices v1 and v2 and the set of neighbours of v1 is a subset of the neighbours of

v2, we can remove v2 and reduce k by 1.

You can visualize that rule this way: As v1 and v2 are connected, at least one of them has to be included in the

vertex cover because of the edge between them.

- If both

v1andv2are selected, this rule doesn't make adifference. - If only on is selected, some of the neighbors have to be included in the vertex cover. In this case it's better if only the subset has to be included. Example:

An implementation of the high-degree rule which removes vertices with more neighbours than the value of k.

We try to "guess" what k will be in two different methods in the class GraphUtil. They are called lower-bound l and upper-bound u.

Because the result r for the vertex cover satisfies l <= r <= u, we can restrict our search.

The methods goal is to find as many non-touching edges as possible. While this is a hard problem to solve precisely, we

tackle it by removing an arbitrary edge e for as long as the edge-set is not empty. Because everytime we also remove the adjacent vertices a of e and their adjacent edges, we make sure no other edges exist that could touch e.

While this method already works, it is not perfect:

Imagine a triangle where you remove an edge e. As you also remove its adjacent vertices a, only one vertex o on the opposite site remains.

Now only o is left without edges. We know this is not correct, we can't have a vertex cover of a triangle with k = 1. Therefore, we must treat triangles differently, which we do at the start of the method lower-bound.

We remove all triangles exhaustively by applying our reduction rules. Additionally, these rules are 100% correct and reduce the error we have in our heuristic.

Most importantly, we can use the lower-bound to check if we need stop following a path in the search tree. If k < l is true at any point in time, we know that the instance can't be solved and we can go back up the search tree immediatly.

The upper-bound method always returns a valid solution for the vertex cover problem. It may or may not be optimal, but in many cases, it is surprisingly close.

It works by removing the vertex with the highest degree and adding 1 to the counter.

If you can for example reduce all of edges the graph by removing the current max-degree-vertex 5 times, the value 5 is an upper-bound.

We can use this to stop our search for k one run earlier than in a naive implementation. If we know that u-1 is not valid solution for k, and we also know that u is a valid solution, we can conlcude u must be the result.

This fix may appear small, but because the runtime for an instance based on k is 2k, testing for a number n takes about as long as testing for 0 to n-1.

This can be seen when adding up the runtimes as a geometric series.

Accordingly, this halfes the runtime on average if the upper-bound is optimal.

An UndoStack was also created, so that we don't have to make a copy of the graph every time we go one layer deeper into the search tree.

This stack saves the inverse operations and if we find out that the path in the search tree were currently following doesn't work, we can trace back to the misleading fork in the tree and take the other path.

While this change was beneficial for the runtime from what our tests say so far (apparently constructors are really bad for performance), the runtime reduction was only about 20%.

Some rules on the other hand changed it by a factor of at least 10 each to put it into persepective.

We have tests both for the class Graph and for SearchTree.

Additionally we started to test our heuristics by calculating by what fraction they were off the actual result.