A kata that I use to teach people how to convert legacy non-testable code to 100% testable code. The different branches contain different "phases". The last phase has all tests implemented.

This kata does not teach about test conventions like AAA (Arrange Act Assert) or how to name your tests. It doesn't dictate whether to use BDD (Business Driven Development) style testing or similar. You still have to agree on your team how to structure that. The kata focuses on the "universal" things that apply to all systems and all teams.

This is not a clean code kata! Please note that the code is far from production code, and is "weird" and "ugly" on purpose for demonstrating testability alone. Yes, clean code goes in hand with testable code, but I have decided to only clean up the minimal amount to still be able to demonstrate testability. I may decide to make a clean code kata later.

These excercises are carefully thought through to allow them to be used on real existing systems too (just follow the steps below on any system, and you'll have a testable system).

First we need to make our system testable, and the key point here is that all of the below changes can be performed in a non-intrusive manner (so that we don't break anything).

As a result of this, the code will look "odd" and perhaps even bad in some areas, but this is temporary (we'll get back to cleaning up in later steps once we have coverage).

To see the original non-testable code: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/blob/master/src/TestabilityKata/Program.cs

Important notes before you throw up

- Yes, there are magic strings several places. This is on purpose to make the kata small and easy to understand. This kata demonstrates testability, not clean code.

- No, we don't log exception details in the

Logger. This is not supposed to be a real "production-ready" logger. It is just a class demonstrating testability, and is by no means ready for production code. - Yes, all classes are defined in one file. Again, to make it easier to understand for everyone - not recommended for production code.

- Yes, we instantiate a

CustomFileWriterperLogger.Logcall because the file name of theCustomFileWriteris based on the log level given as argument to that method, and because theCustomFileWriterrequires it in its constructor. This could easily be optimized away, but the point of this code is again to demonstrate testability in all aspects and object composition that could be found in production.

This allows objects to actually have some form of "state" that is scoped to themselves and their own lifetime rather than being application-scoped. Essentially a static class is just "some functions and some global state operating somewhere" in your program. Statics also rarely actually save a lot of lines of code, and they can't be faked out.

If your static dependency has too many references, it can be hard to "just" convert into non-statics. In this case, take your existing static method (let's say it's called SendMail) and rename it into SendMailStatic so that all references will point to this method for backward compatibility. Then take the body of this method and move it into a new non-static method called SendMail. Finally, change the SendMailStatic method so that it instantiates a new instance of itself and calls the non-static SendMail function on that instance. This allows you to take "baby steps" in getting rid of static sickness instead of doing it all. Just remember that static functions can't be faked out.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-1

Important notes before you throw up

- This is a temporary step - don't worry. We will clean up later.

Step 2. Apply manual dependency injection to non-static class dependencies where only one instance of a dependency per class is required

Doing this is part of following the Open/Closed principle (the "O" in SOLID). By injecting dependencies in from the outside, we essentially allow tests to "fake out" the "internals" of our class if they want to, and provide their own versions of dependencies for this class. As an example, it allows us to provide our own Logger for our Program, or our own MailSender for our Logger, even if Logger or MailSender was a third party NuGet package that we couldn't change.

Note that the Logger's CustomFileWriter class dependency has not been converted yet in this step - that will be done in the next step, since the constructor parameter for file name depends on the log level, which is only available by the time the Log method is called.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-1...step-2

Step 3. Apply manual dependency injection via factories for scenarios where creation of objects at runtime is required

This is about continuing step 2, but for the Logger's CustomFileWriter dependency. Since it is created in the Log method and the file name to log to depends on the log level given in this method, we can't just inject a CustomFileWriter into the constructor. Here, we instead create a CustomFileWriterFactory which we then inject, and this factory then injects the dependencies required for creating a CustomFileWriter.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-2...step-3

Important notes before you throw up

- Yes, we create a whole

CustomFileWriterFactoryhere to createCustomFileWriterinstances. We could have used aFunc<T>, but I wanted this code to be readable and understandable by all levels of programming. Once again, this kata focuses on testability, not clean code.

This is about applying the Dependency Inversion principle (the D in SOLID) and making our program more losely coupled. A dependency declared as a class is tightly coupled to "what that class is" (for instance that it's a Tiger class). If it was declared as an interface instead - for instance IAnimal which then had a Bite method, then it would instead just be coupled to "something that can bite".

Within testability this allows us to make "fake" implementations of dependencies (for instance, a fake MailSender which doesn't actually send e-mails when running unit tests). More on this later when we get to writing the tests.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-3...step-4

Important notes before you throw up

- Yes, while following the Dependency Inversion principle, we don't follow it exactly by the book here. If we did, we most likely would compose many small interfaces per class, that each defines the minimum methods that make that interface live up to its responsibility. Once again, this is not the case because I wanted the kata to be readable and focus on testability, not necessarily clean code. The important part for the testability here is to be backed by interfaces - not that they are small and clean. Besides, the classes we are dealing with are small in the first place, and may not make sense to split up.

It should be noted that these tests only focus on the "unique" scenarios where something needs to be handled differently from step to step. In general, both negative and positive outcomes of tests (throwing exceptions and/or passing) and most input scenarios should be tested.

This class is relatively important to have coverage on, as it is our main program. Similarly, it's a good idea to determine the right areas to test. Code coverage is not everything. It can be a distraction.

Technically here we could create our own FakeEmailSender class, pass it to our Program instance when instantiating it, and then having this FakeEmailSender report what arguments its SendMail method was called with, and pass the test if these arguments are correct and the method was indeed called.

However, for now we will skip all this and use NSubstitute, which can magically at runtime (it uses the TypeBuilder class in C# for this) create a new class that implements a given interface, and record calls and change its runtime behavior.

So to summarize, this step is about making a fake IEmailSender at runtime using NSubstitute, passing this into the Program instance as a dependency, and then (after executing Program.Run()), we check that the IEmailSender.SendMail method was called with the right arguments.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-4...step-5

Similarly to step 5, we here need to have NSubstitute create a fake dependency which throws an exception. We then run the program, and need to make sure that the Logger's Log method was called with a log level of Error.

Pro-tip: Similarly to how NSubstitute allows you to see if a specific method was called, it can also check if a method was not called. It would be a good idea to also cover the negative cases (testing that the Log method is not called when we don't throw an error), but we are skipping that for now.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-5...step-6

It turns out that this class has no dependencies and was already testable all along - so this should be easy. No faking required here.

Step 7. Test that the mail sender throws an exception if the e-mail is invalid (doesn't contain a @)

Here we can just invoke the method directly and put an ExpectedExceptionAttribute on our test to describe that it should pass instead of failing when a specific exception is thrown.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-6...step-7

The reason we call this an integration test (even if we fake out the EmailSender), is because the CustomFileWriter actually accesses the file system. If we wanted to fake the file system out as well, we could make our own CustomFile class instead of the System.IO.File static reference. However, it is also important to remember that too many abstractions can lead to low code readability, which is very bad and often worse than the extra coverage we miss out on.

It is important to note that an integration test focuses more on testing a "feature" than testing a "specific function or unit". Therefore, instead of tests called CallingSignUpInvokesMailSenderToSendActivationEmail, we may have tests that look at it from a feature or business perspective, such as WhenISignUpIGetAnActivationEmail.

Since we have decided not to make our own fakeable System.IO.File decorator, we have to make a test here that makes sure the file actually doesn't exist on disk before appending lines to it, to see if an e-mail is being sent out. We still need a fake MailSender for this though.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-7...step-8

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

Important notes before you throw up

- In this phase we don't clean up the magic strings or optimize the program flow. This is on purpose, to keep the kata very small and understandable. We're not trying to teach clean code - we're trying to teach testability.

- The steps below focus on cleaning the test code primarily, not the code of the main program as much.

In each test we are faking out several things and repeating ourselves over and over, violating the DRY principle (Don't Repeat Yourself). We should unify the generic setup logic for each test into a test initialization method.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-8...step-9

For this, step I recommend Autofac. Have Autofac register specific interfaces as specific implementations (you can do this manually for each type or automatically for all types in the assembly), and have your brand new IOC container construct your Program instead - injecting all of its dependencies automatically. Also modify the tests so that they use the IOC container for their types too. At first, this may seem counter-productive. We will see why it makes sense in step 11.

Note that the configuration of Autofac should ideally be turned into an Autofac module, so that it can be re-used by your test projects See the changeset below if you are in doubt of what this means.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-9...step-10

Documentation: https://github.com/ffMathy/FluffySpoon.Testing

By introducing auto-faking and extracting the logic for creating the container into a separate class, we can automatically scan for a class' dependencies in the constructor and register them as fakes. This is great, because if a new dependency is added to a class, our existing tests won't break, and they will still compile.

You may think "why are we automatically faking all dependencies? What if I want to test the interaction between a class and its real dependencies?" - well, in that case we're talking about an integration test, and not a unit test. Autofaking is not useful for integration tests.

After this step, run all tests to make sure you haven't broken anything.

To see this change: https://github.com/ffMathy/testability-kata/compare/step-10...step-11

TL;DR: Classes should do just one thing. Make sure your classes only have one reason to change.

Testability aspect: Decreases the amount of tests that need to be written to test the same things. Reduces duplication. Reduces chance of tests breaking over time when your system changes.

TL;DR: Objects should be open for extension, but closed for modification. You should be able to control "how" a class uses its dependencies without changing that class' code.

Testability aspect: Allows us to fake dependencies of a class, and recording the class' usage of these dependencies in unit tests. This way, we only test the "unit" itself, and not everything it interacts with - this would be covered by individual unit tests as well.

TL;DR: We should be able to substitute any object with a different object implementing the same interface, without causing nasty side-effects. If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, but needs batteries, you probably have the wrong abstraction.

Testability aspect: This makes it possible for us to substitute and fake any dependency of a class, and count on that it won't change the flow of the program into something bad.

TL;DR: An interface should have as few methods and properties as possible, while still living up to its responsibility. A lot of small interfaces is often easier to test than a few large ones - and a class can implement many interfaces.

Testability aspect: More atomic interfaces may lead to more atomic tests. We can also decide to remove an interface implementation from an object without it requiring a big redesign of our tests.

TL;DR: A class should not care about what its dependencies "are", but what they "do". Depend on interfaces (what something "does"), not classes (what something "is").

Testability aspect: By depending on interfaces (something that "does" something) we can substitute that functionality out and fake it for a class' dependencies.

Inheritance (especially used entirely for code-reuse and not polymorphism) can potentially break a large part of the SOLID principles (except Open/Closed principle, which can be based on inheritance), and make your code harder to test.

A classic example is having some UserService which inherits from a BaseService to re-use methods that are defined on that base service. The reason this can be bad for testability is that if you have 100 services and need to test them all, then all of the functionality defined in BaseService would have to be faked out and configured for all these 100 tests.

Instead, you could use composition (which by the way only makes you spend one extra line of code). This lets you make a test for BaseService separately, and then only focus on testing the things that are unique to the individual services on top of that.

Note that this only applies if your base class is only there for code-reuse and not polymorphism. If extracting the class into a separate class would break encapsulation by making your protected fields public or if the base class is small enough, it may not worth it.

More information: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Composition_over_inheritance

Here we have the BaseMethod defined on Bar for quick code-reuse. For each test we would now have to fake out and configure BaseMethod for all of our tests.

public class Foo: Bar {

public void MainMethod() {

base.BaseMethod();

}

}

public class Bar {

public void BaseMethod() { }

}Note how we only lose very few lines of code! Think about this for a second - not bad for a more losely coupled system.

public class Foo

{

Bar bar;

public Foo(Bar bar) {

this.bar = bar;

}

public void MainMethod() {

bar.BaseMethod();

}

}

public class Bar {

public void BaseMethod() { }

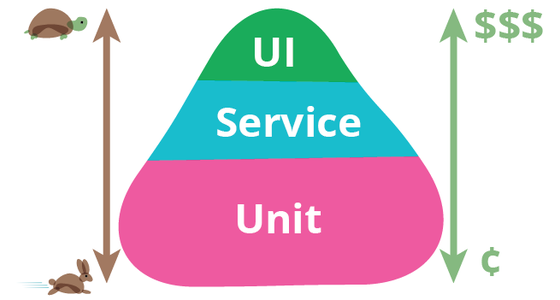

}The higher we go abstraction wise, the more maintenance is required (they get more fragile to changes), the slower the tests run and the more time they take to build and get running. However, unit tests don't make integration tests obsolete or the other way around. Both are needed to gain a healthy coverage in your system.

Just a regular geek: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mathiaslorenzen/