Udacity Self-Driving Car Project 4: Advance Lane Finding

Objective: Use OpenCV to create a software pipeline to identify the lane boundaries in video from a front-facing camera on a car.

Special Thanks: Goes to Kyle Stewart-Frantz for spending time to peer review my work and made sure I double check on its sanity.

NOTE: Please be aware that this report is a snapshot in time and also a journal of my wondering into discovery. A lot of what is written here is about my experiments and logs of what worked and what did not, and my detective reasoning as to why. Notes about what to try next and what we are leaving for future work, so read on dear friend!

Fundamentally, this Python based command line interface (CLI) software is structured internally as a software pipeline, a series of software components, connected together in a sequence or multiple sequences (stages), where the output of one component is the input of the next one. Our pipeline implementation is made up of 7 major components, and we will go into them in detail in section 1.2. The majority of its software is based on the Open Source Computer Vision Library (OpenCV). OpenCV is an open source computer vision and machine learning software library. OpenCV was built to provide a common infrastructure for computer vision applications and to accelerate the use of machine perception in the commercial products. More about OpenCV can be found at http://opencv.org/.

The software must meet the following design goals to be successful:

- Apply a distortion correction to the raw image

- Use color transforms, gradients, etc., to create a threshold binary image

- Apply a perspective transform to rectify binary image ("birds-eye view")

- Detect lane pixels and fit to find lane boundaries

- Determine curvature of the lane and vehicle position with respect to center

- Warp the detected lane boundaries back onto the original image

- Output visual display of the lane boundaries and numerical estimation of the lane curvature and vehicle position.

In addition, we would also like to implement a software pipeline that will:

- Extend the rectified lane lines as far to the horizon as possible

- Keep the correct aspect ratio when projecting the perspective view down to a planar ('birds-eye') view

- Optimize on speed of execution: When not in diagnostics mode, try to spend less time processing each frame. Where possible, pass the last frames information instead of recomputing it. Memory is less expensive than CPU time for real-time applications.

To achieve the design goals, we will create a pipeline made of 7 components. Each of these are described here briefly.

- CameraCal: Python class that handles camera calibrations operations

- ImageFilters: Python class that handles image analysis and filtering operations

- ProjectionManager: Python class that handles projection calculations and operations

- Line: Python class that handles line detection, measurements and confidence calculations and operations. There are two instances of this class: LeftLane and RightLane.

- RoadManager: Python class that handles image, projection and line propagation pipeline decisions

- DiagManager: Python class that handles diagnostic output requests

- P4pipeline.py: Main Python CLI component that handles input/output filename checking, option selections and media IO.

This is a block diagram of how the classes are organized to process an image or a video (sequence of images):

NOTE: This project started out as a Jupyter Notebook, but was abandoned because of versioning issues, and was getting too large. However, we will use the graphics produced by the last version of the Notebook in this document. An HTML version of the notebook can be accessed here.

The P4pipeline.py CLI can be executed in the command line using the following method. For infilename, it will accept JPEG and PNG image files, or MPEG4 video files. Output file extension should match the input as to type of file (single image versus video.)

usage: python P4pipeline.py [options] infilename outfilename

DIYJAC's Udacity SDC Project 4: Advanced Lane Finding Pipeline

positional arguments:

infilename input image or video file to process

outfilename output image or video file

optional arguments:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--diag DIAG display diagnostics: [0=off], 1=filter, 2=proj 3=full

--notext do not render text overlay

NOTE: P4pipeline.py is implemented with fail-safe, so if your specified output file is detected to exists, the pipeline will refuse to run and overwrite it. If this situation occurs, either specify another output filename, or delete the original output file before trying again.

The following sections describe the implementation of the pipeline in detail and why this particular implementation was chosen. Some factors of the architecture decision was based on efficiency, or observed improvements with video processing that were not observed when processing single images. Where such observations were made, the subsequent improvements mostly improved both single image and video processing. Cases where the improvements made single image processing suffer, we decide to make the change anyway, since we are bias toward making the lane boundaries identification video processing better.

One of the goals of the image processing is distortion correction. Image distortion occurs when a camera looks at 3D objects in the real world through lens and transforms them into a 2D image when this transformation is not perfect. The distortions in an image can:

- Change the appearent size of an object

- Change the apparent shape of an object

- Cause an object's appearance to change depending on where it is in the field of view

- Make objects appear closer or farther away than they actually are.

Cameras use curved lenses to form an image, and light rays often bend a little too much or too little at the edges of these lenses. This creates an effect that distorts the edges of images, so that lines or objects appear more or less curved than they actually are. This is called radial distortion, and it is the most common type of distortion. Another type of distortion, is tangential distortion. This occurs when a camera’s lens is not aligned perfectly parallel to the imaging plane, where the camera film or sensor is. This makes an image look tilted so that some objects appear farther away or closer than they actually are. To correct for these two types of distortions, we will be using a technique call camera calibration where black and white pictures of known good chessboard images are placed in various positions and then taken with the camera and lens used for subsequent image or video captures.

OpenCV has a set of functions that will be able to use these chessboard images and calculate the necessary correction matrix using the following formulas for radial distortion correction:

and the following formulas for tangential distortion correction:

You can read more about the technique deployed by OpenCV here. For this part of the pipeline, we obtained a set of 20 black-white chessboard images taken by the camera and lens used for the front-facing camera. The following set of pictures shows we used the chessboard images, located the chessboard corners and apply distorted correction on all of them using the OpenCV libraries.

Once we are done with camera calibrations, we can save the results of the distortion correction matrix generated by the OpenCV calibrateCamera function into a pickle file for later usage without having to regenerate them again and again. The generation, saving to pickle and later retrievals are all handled by the CameraCal module mentioned earlier, and you may view it here.

After generating the camera undistortion matrix, we can now start using test images to practice finding lane lines using our software pipeline as we are in development.

We were given a set of eight test images to start with. However, not being statisfied with just the eight, we added an additional fifteen images from the project, challenge and harder challenge videos to bring the total number of test images to twenty-three. They are shown in the next session where we undistort them like the camera calibration chessboard images.

The first thing the P4pipeline does when it starts its pipeline modules is to use the ImageFilters module to correct the distortion in the image using the generated distortion correction matrix obtained by the CameraCal module using camera calibration techniques as discussed in section 3.1. Below, the twenty-three raw/unprocessed test images are shown on the left and the results of the distortion correction is shown on the right. They may look very similar until you look at their edges. The distortion corrected images have a smaller field of view than the uncorrected image.

Next the ImageFilters module will apply filters to the images in an attempt to isolate the pixels that makes the lane lines. In each of the subsections, we will describe a filter deployed by the ImageFilters module either in sequence or in combination. You may view the ImageFilters module here.

One of the most difficult lane lines to isolate are the yellow lane lines. Since they use only two of the three RGB (Red, Green, Blue) color components, Red and Green, we can just use brightness (Luma) to detect them like white lines. This become perticularly difficult when we encounter yellow lane lines in images with poor visibility:

Using thresholding on the red color channel in an RGB colorspace, we can render this image from the poor visibility image:

How we do it is we apply the following to a RGB image with pixels in unsigned 8-bit integer:

rEdgeDetect = img[:,:,0]/4

rEdgeDetect = 255-rEdgeDetect

rEdgeDetect[(rEdgeDetect>220)] = 0

What this filter does is that it compresses the red color channel space to 1/4 its normal value, then it inverts it so that its lowest value now becomes its highest. Then a threshold is selected to drop any value higher than it to be 0, in this example the value 220 was selected as the threshold. (Remember, since we divided by 4, our range became (255-63 to 255), or (192 to 255.) What we are left with is a set of pixels that at higher than normal intensity compressed and then forced into a higher set of values within the red color channel. However, this filter does not work for all cases, and become perticularly difficult when we encounter yellow lane lines drawn on nearly white concrete backgrounds as shown here:

So, we need to continue searching for additional image filters.

The Sobel operators combine the idea of Gaussian smoothing and differentiation filters and is at the heart of Canny edge detection algorithm. Since the filter takes the first, second, third, or mixed image derivatives of the grayscaled image, the result is more or less resistant to any noise in the image and reliable edges are produced. More about the OpenCV libraries implementation of the Sobel operator is available here.

The Sobel image derivitives in the X direction is given by the following formula assuming a 3x3 kernel.

The Sobel image derivitives in the Y direction is given by the following formula assuming a 3x3 kernel.

Kernels must be 1, 3, 5, or 7. Kernels of larger size will provide a softer smoother gradient image. For our purpose, we need sharp edges, so a kernel of 3 was defaulted. Once we have the results, we need to take the absolute value of the derivative or gradient and scale them back to 8-bit unsigned integers, since we will be, in essence, using it as a bitmap to isolate the lane lines. The ImageFilters module uses the following code to create the filter:

# Define a function that applies Sobel x or y,

# then takes an absolute value and applies a threshold.

def abs_sobel_thresh(self, img, orient='x', thresh=(0, 255)):

# Apply the following steps to img

# 1) Convert to grayscale

# 2) Take the derivative in x or y given orient = 'x' or 'y'

# 3) Take the absolute value of the derivative or gradient

# 4) Scale to 8-bit (0 - 255) then convert to type = np.uint8

# 5) Create a mask of 1's where the scaled gradient magnitude

# is > thresh_min and < thresh_max

# 6) Return this mask as your binary_output image

gray = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY)

if orient == 'x':

sobelx = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 1, 0)

abs_sobel = np.absolute(sobelx)

if orient == 'y':

sobely = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 0, 1)

abs_sobel = np.absolute(sobely)

# Rescale back to 8 bit integer

scaled_sobel = np.uint8(255*abs_sobel/np.max(abs_sobel))

# Create a copy and apply the threshold

ret, binary_output = cv2.threshold(scaled_sobel, thresh[0], thresh[1], cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

# Return the result

return binary_output

Later on, we will discuss how the ImageFilters module will filter the images differently based on the images' statistics that we will explain in section 3.2.3.5, Image Analysis. But for now, for test2 image, as an example of how this filter works:

We applied a threshold of (25,50) for Sobel in the X direction and (50, 150) for Sobel in the Y direction to get this image where Sobel X is in the red color channel and Sobel Y is in the blue color channel:

Again this is still not enough, because we still get nasty results of missing yellow lane line from that test1 image using this filter:

The idea of taking the magnitude (Sobel XY) of the Sobel X and Y results is to see if there is a distance factor in the individual components in the gradient that can be used to further isolate the lines/edges in the image. Sobel XY is calculated by squaring the X and Y components of the Sobel operator and then take the square root of their sum, and, in essence, calculate the magnitude of changes in intensity that being experienced by that pixel in that image. If there is an absence of any one of the components for a particular pixel, then the value produced at that pixel is just the same as for the Sobel X or Y component remaining. The formula is:

The ImageFilters module uses the following function to create the filter:

# Define a function that applies Sobel x and y,

# then computes the magnitude of the gradient

# and applies a threshold

def mag_thresh(self, img, sobel_kernel=3, mag_thresh=(0, 255)):

# Apply the following steps to img

# 1) Convert to grayscale

gray = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY)

# 2) Take the gradient in x and y separately

sobelx = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 1, 0, ksize=sobel_kernel)

sobely = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 0, 1, ksize=sobel_kernel)

# 3) Calculate the magnitude

gradmag = np.sqrt(sobelx**2 + sobely**2)

# 5) Scale to 8-bit (0 - 255) and convert to type = np.uint8

scale_factor = np.max(gradmag)/255

gradmag = (gradmag/scale_factor).astype(np.uint8)

# 6) Create a binary mask where mag thresholds are met

ret, mag_binary = cv2.threshold(gradmag, mag_thresh[0], mag_thresh[1], cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

# 7) Return this mask as your binary_output image

return mag_binary

The idea of taking the directional Sobel is a to try to isolate edges based on an orientation. It is simply the arctangent of the y-gradient divided by the x-gradient. The formula is:

Each pixel of the resulting image contains a value for the angle of the gradient away from horizontal in units of radians, covering a range of −π/2 to π/2. An orientation of 0 implies a horizontal line and orientations of +/−π/2 imply vertical lines. The ImageFilters module uses the following function to create the filter:

# Define a function that applies Sobel x and y,

# then computes the direction of the gradient

# and applies a threshold.

def dir_threshold(self, img, sobel_kernel=3, thresh=(0, np.pi/2)):

# Apply the following steps to img

# 1) Convert to grayscale

gray = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_RGB2GRAY)

# 2) Take the gradient in x and y separately

sobelx = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 1, 0, ksize=sobel_kernel)

sobely = cv2.Sobel(gray, cv2.CV_64F, 0, 1, ksize=sobel_kernel)

# 3) Calculate the direction of the gradient

# 4) Take the absolute value

with np.errstate(divide='ignore', invalid='ignore'):

dirout = np.absolute(np.arctan(sobely/sobelx))

# 5) Create a binary mask where direction thresholds are met

dir_binary = np.zeros_like(dirout).astype(np.float32)

dir_binary[(dirout > thresh[0]) & (dirout < thresh[1])] = 1

# 6) Return this mask as your binary_output image

# update nan to number

np.nan_to_num(dir_binary)

# make it fit

dir_binary[(dir_binary>0)|(dir_binary<0)] = 128

return dir_binary.astype(np.uint8)

Again, later on, we will discuss how the ImageFilters module will filter the images differently based on the images' statistics that we will explain in section 3.2.3.5, Image Analysis. But for now, for test2 image, as an example of how this filter works:

We applied a threshold of (50, 250) for Sobel XY (Magnitude) and (0.7, 1.3) for Sobel directional (we are looking for verticle lines) to get this image where Sobel XY is in the green color channel and Sobel Directional is in the blue color channel:

Again this is still not enough, because we still get nasty results of missing yellow lane line from that test1 image using this filter:

Obviously by now, we know that Sobel operations, in all of its wonderful various forms, will not fulfill our yellow lane line finding needs. Its now time to look at other colorspaces for inspirations. This time we will look at HLS (Hue, Lightness and Saturation). Hue represents color independent of any change in brightness. Lightness represents luminacity or brightness, and can be compared to converting an RGB image to grayscale. Saturation is a measurement of colorfulness as compared to whiteness. The HLS (hue, lightness, saturation) color space is a cylindrical representation of the RGB model. Hue is measured in degrees around the circumference of the cylinder. Red is at 0°, green at 120°, and blue at 240°, then wrapping back to red at 360°. Note that there is a discontinuity at 0° and 360°. Saturation is measured in percent from the center of the cylinder to its radius. Lightness is measured in percent from the bottom to the top of the cylinder. You can find more information about colorspaces here and here

For our lane finding needs, we will drop the Lightness color channel as a means of filtering and look at Hue and Saturation color channels to threshold instead. We are interested in filtering for the yellow lane lines against white background since the Sobel functions are excellent in filtering for edge detection based on luminance already. The Hue color channel is an obvious candidate for filter yellow lane lines, and Saturation (value of color away from white) will help too. The ImageFilters module uses the following function and OpenCV cvtColor function to create these two filters:

# Define a function that thresholds the S-channel of HLS

def hls_s(self, img, thresh=(0, 255)):

# 1) Convert to HLS color space

# 2) Apply a threshold to the S channel

# 3) Return a binary image of threshold result

hls = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_RGB2HLS)

s = hls[:,:,2]

retval, s_binary = cv2.threshold(s.astype('uint8'), thresh[0], thresh[1], cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

return s_binary

# Define a function that thresholds the H-channel of HLS

def hls_h(self, img, thresh=(0, 255)):

# 1) Convert to HLS color space

# 2) Apply a threshold to the S channel

# 3) Return a binary image of threshold result

hls = cv2.cvtColor(img, cv2.COLOR_RGB2HLS)

h = hls[:,:,0]

retval, h_binary = cv2.threshold(h.astype('uint8'), thresh[0], thresh[1], cv2.THRESH_BINARY)

return h_binary

Again, later on, we will discuss how the ImageFilters module will filter the images differently based on the images' statistics that we will explain in section 3.2.3.5, Image Analysis. But for now, for test2 image, as an example of how this filter works:

We applied a threshold of (50, 100) for Hue and (88, 190) for Saturation to get this image where Hue is in the blue color channel and Saturation is in the red color channel:

These two filters appears to be mutually exclusive. The filter created by using thresholding against the Hue color channel can be used to mask out the white background. The filter created by thresholding against the Saturation color channel can be used for finding the yellow lane lines. In practice, this works quite well, even against test1 image's nasty yellow lane line against its white concrete bridge background using this filter:

Success at Last!

As can be seen from the previous set of filters, not a single one of them can produce the lane line isolation that we would like to achieve. However, in combination, they very well may! Below was the first iteration of the filter combination we attempted for the Project video. The ImageFilters module uses this combination at the beginning:

combined[((gradx > 0) | (grady > 0) | ((magch > 0) & (dirch > 0)) | (sch > 0)) & (shadow == 0) & (rEdgeDetect>0)] = 35

And this combination produced the following combination at the end as indicated by the Final Mask Combination column.

The resulting threshold binary image worked well in the video mostly, but was brittle. There were still many places it would fail. If there were only a way we could apply multiple combinations of thresholds to what the images needed for finding lane lines. As it turned out, there was! In comes image analysis.

What is at issue is that we were applying the same thresholds on different images with different lighting conditions. As with previous Machine Learning techniques, we learned that normalization of the data were essential for being able to retrieve useful information. This is no exception. The idea is that based on statistics of the images we have, we should be able to figure out what is the optimum filter combination for each type of image, so that we don't have to treat them all the same. So, first we have to generate a set of useful information on the images as a base to try to figure out how to generate more tailored filter combinations. Below are the results of this study. The ImageFilters module uses the imageQ function to generate the statics:

But now that we have the statistics, how about just correcting the image ourselves? That is what we will try next!

Now that we have some statistics on the images, our reasoning is could we not just use some digital image techniques to rebalance the image? We attempted to do this in ImageFilters module using its balanceEx function as shown below:

NOTE: We could have tried the Gamma correction function in OpenCV, but wanted to experiment with different thresholding and masking techniques.

def balanceEx(self):

# separate each of the RGB color channels

r = self.curRoadRGB[:,:,0]

g = self.curRoadRGB[:,:,1]

b = self.curRoadRGB[:,:,2]

# Get the Y channel (Luma) from the YUV color space

# and make two copies

yo = np.copy(self.curRoadL[:,:]).astype(np.float32)

yc = np.copy(self.curRoadL[:,:]).astype(np.float32)

# use the balance factor calculated previously to calculate the corrected Y

yc = (yc/self.roadbalance)*8.0

# make a copy and threshold it to maximum value 255.

lymask = np.copy(yc)

lymask[(lymask>255.0)] = 255.0

# create another mask that attempts to masks yellow road markings.

uymask = np.copy(yc)*0

# subtract the thresholded mask from the corrected Y.

# Now we just have peaks.

yc -= lymask

# If we are dealing with an over exposed image

# cap its corrected Y to 242.

if self.roadlrgb[0] > 160:

yc[(b>254)&(g>254)&(r>254)] = 242.0

# If we are dealing with a darker image

# try to pickup faint blue and cap them to 242.

elif self.roadlrgb[0] < 128:

yc[(b>self.roadlrgb[3])&(yo>160+(self.roadbalance*20))] = 242.0

else:

yc[(b>self.roadlrgb[3])&(yo>210+(self.roadbalance*10))] = 242.0

# attempt to mask yellow lane lines

uymask[(b<self.roadlrgb[0])&(r>self.roadlrgb[0])&(g>self.roadlrgb[0])] = 242.0

# combined the corrected road luma and the masked yellow

yc = self.miximg(yc,uymask,1.0,1.0)

# mix it back to the original luma.

yc = self.miximg(yc,yo,1.0,0.8)

# resize the image in an attempt to get the lane lines to the bottom.

yc[int((self.y/72)*70):self.y,:] = 0

self.yuv[self.mid:self.y,:,0] = yc.astype(np.uint8)

self.yuv[(self.y-40):self.y,:,0] = yo[(self.mid-40):self.mid,:].astype(np.uint8)

# convert back to RGB.

self.curRoadRGB = cv2.cvtColor(self.yuv[self.mid:self.y,:,:], cv2.COLOR_YUV2RGB)

The resulting image is shown below.

NOTE: Notice that the images are only corrected at the bottom half? This is because we wanted to save on processing time and storage space. Since we needed to find lane line boundaries, we just needed to correct the part of the image that contains them: the lower half!

Once we had the new balanced lower half of the image where the lane lines were, we expected an easy win for just picking an optimal binary threshold combination. This was not the case, as can be seen here. While a lot of images now have lane lines that are easier to identify, it seems we still need multiple filter combinations.

Although this is a feature worth further investigation, it is not an easy win, so we are placing it on hold. Instead we will a set of Image filter combination for the rest of this project.

In the end, we decided to create five combinations. One of them worked very well on the Project Video and another of the five worked very well on the Challenge Video. The five combination's thresholds are described in the table below:

| Filter | Combination 1 | Combination 2 | Combination 3 | Combination 4 | Combination 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red | (> 210) | (> 210) | (>220) | (>220) | (>220) |

| Sobel X | (25, 100) | (25, 100) | (25, 100) | (30, 100) | (25, 100) |

| Sobel Y | (50, 150) | (50, 150) | (50, 150) | (75, 150) | (50, 150) |

| Sobel XY | (50, 250) | (50, 250) | (30, 150) | (30, 150) | (30, 150) |

| Sobel Dir | (0.7, 1.3) | (0.7, 1.3) | (0.6, 1.3) | (0.6, 1.3) | (0.5, 1.3) |

| Hue | (50, 100) | (50, 100) | (125, 175) | (125, 175) | (130, 175) |

| Saturation | (88, 190) | (88, 250) | (20, 100) | (20, 100) | (20, 80) |

Additional filter combinations may be defined later. The RoadManager module currently uses the following logic to decide which filter combination to apply to the image. We will discuss more about the RoadManager in sections 3.2.5, Lane Line Identification and 3.2.6, Lane Line Measurements.

# detected cloudy condition!

if self.curImgFtr.skyText == 'Sky Condition: cloudy' and self.curFrame == 0:

self.cloudyMode = True

# choose a default filter based on weather condition

# NOTE: line class can update filter based on what it wants too

# (different for each lane line).

if self.cloudyMode:

self.curImgFtr.applyFilter3()

self.maskDelta = 20

self.leftLane.setMaskDelta(self.maskDelta)

self.rightLane.setMaskDelta(self.maskDelta)

elif self.curImgFtr.skyText == 'Sky Condition: clear' or \

self.curImgFtr.skyText == 'Sky Condition: tree shaded':

self.curImgFtr.applyFilter2()

elif self.curFrame < 2:

self.curImgFtr.applyFilter4()

else:

self.curImgFtr.applyFilter5()

And as explained earlier, we had some versioning issues with the Jupyter notebook and that was abandoned, but wanted to show what was working up to that point. In the newer CLI implementation of the software pipeline, you may generate a diagnostic screen of the image filters using the following syntax:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=1 <inputfile> <outputfile>

The following sample run:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=1 test_images/test1.jpg output_images/test1diag1.jpg

Produces this output:

You may have noticed that there is a curious yellow line running across the right bottom panel of the test1diag1.jpg diagnostic screen, and ask what that is. This is our attempt at detecting the road horizon in the image as part of the ImageFilter class. It uses the Sobel XY (Magnitude) as a threshold for locating the horizon using this algorithm:

# function to detect the horizon using the Sobel magnitude operation

def horizonDetect(self, debug=False, thresh=50):

if not self.horizonFound:

img = np.copy(self.curRoadRGB).astype(np.uint8)

magch = self.mag_thresh(img, sobel_kernel=9, mag_thresh=(30, 150))

horizonLine = 50

while not self.horizonFound and horizonLine<int(self.y/2):

magchlinesumd = np.sum(magch[horizonLine:(horizonLine+1),:]).astype(np.float32)

if magchlinesum > (self.x*thresh):

self.horizonFound = True

self.roadhorizon = horizonLine + int(self.y/2)

if debug:

self.diag4[horizonLine:(horizonLine+1),:,0] = 255

self.diag4[horizonLine:(horizonLine+1),:,1] = 255

self.diag4[horizonLine:(horizonLine+1),:,2] = 0

else:

horizonLine += 1

But why should we care? In the next stage of the pipeline, we will be performing a perspective to plane transform, and one of the issues with doing these types of transforms are its nonlinearity, particularly at the vanishing point, which is one of the points along the horizon of the perspective image. As you approach the vanishing point, a short vertical distance in pixel space, represent a very large distance when projected in birds-eye view. We will describe this in more details in section 3.2.6, Lane Line Measurements.

One of the major difference between Project 1 and 4, is the requirement to apply a perspective transform to rectify the binary road image to a ("birds-eye view"). The reason to do this is to more easily identify the lane lines and to make curvature measurements. We will use the Pinhole Camera mathematical model to transform the perspective view of the image plane into a planar 'birds-eye' view (view looking down from above). See here for the mathematics involved in doing projections in a Pinhole Camera model.

But in general, we are using the theoretical geometry of the pinhole camera model to project the (Y1, Y2) perspective image plane to a (x1, x2, x3) 3D space. Then we will use just the (x1, x3) coordinates for the 'birds-eye' view mapping. This equation gives how we derive at the (x1, x2, x3) coordinates giving (y1, y2) coordinates:

Where f is the focal length of the pinhole camera. But where do we find the focal length? Recall we did the Camera Calibration in section 3.1? Part of the calculation was also to derive the camera focal lengths. See here for all of the mathematics involved in doing Camera Calibration Calculations in OpenCV. Once we have the camera focal length, we need to calculate the transform from the image plane to the 'birds-eye' view plane. This involves calculating what is known as the Camera Matrix. This matrix is a 3x4 matrix which describes the mapping of a pinhole camera from 3D points in the world to 2D points in an image.

We will be using OpenCV getPerspectiveTransform and cv2.warpPerspective functions to do the heavy lifting of deriving the Camera Matrix and performing the transformation from the perspective image plane to the 'birds-eye' view, but we still need to find four corners points on the road surface to project on to a planar "birds-eye view. Project 1 back to the rescue with the Houghline function. Recall we used the Houghline function to approximate the lane line locations. Those identified lane lines are parallel in perspective, since they are suppose to form the lane lines which are also in parallel in perspective. If we assume that the base of the lane lines, where the lane meets the bottom of the image, is also parallel to another line that is near the horizon, then we have a rectangle that are formed by the two sets of parallel lines (see the red lines in the left image below.) We can use the corner points of this rectangle as our source points and then map them to a planar surface by warping their points as describe below using the orange and light blue dashed arrow lines. The blue dashed line indicates that the image on both sides of the transform are symmetric and will remain symtric during the transformations. Therefore, we can repurpose so of the old codes from Project 1 to perform the initial task of not just estimate the lane lines, but to also calculate our source points. It is important that we are able to calculate this dynamically because, we do not know in advance if the camera is facing a road going uphill or downhill and the perspective transform for them will be quite different and make it harder to identify lane lines.

We will be using our ProjectionManager module to handling these OpenCV HoughLinesP calculations and initial source point generation. In general, we will be using the HoughLinesP function to find the left and right lane lines. Using linear algebraic calculations, we will identify the Y intercept of both lines. This, in theory, is where both the horizon is at and also the vanishing point in perspective. From there, we will have to calculate a "backoff" from the horizon, since points near the vanishing point is theoretically at infinity and will not be useful. Our current rule of thumb for a standard backoff during initialization is at 30 pixels; however, this is now no longer static and can be dynamically change during video processing based on detected horizon from the ImageFilter module which we will describe in section 3.2.6, Lane Line Measurements. Below is the code segment that the ProjectionManager module uses to perform the backoff calculations:

# find the right and left line's intercept,

# which means solve the following two equations

# rslope = ( yi - ry1 )/( xi - rx1)

# lslope = ( yi = ly1 )/( xi - lx1)

# solve for (xi, yi): the intercept of the left and right lines

# which is: xi = (ly2 - ry2 + rslope*rx2 - lslope*lx2)/(rslope-lslope)

# and yi = ry2 + rslope*(xi-rx2)

xi = int((ly2 - ry2 + rslope*rx2 - lslope*lx2)/(rslope-lslope))

yi = int(ry2 + rslope*(xi-rx2))

# calculate backoff from intercept for right line

if rslope > rightslopemin and rslope < rightslopemax: # right

ry1 = yi + int(backoff)

rx1 = int(rx2-(ry2-ry1)/rslope)

ry2 = ysize-1

rx2 = int(rx1+(ry2-ry1)/rslope)

cv2.line(img, (rx1, ry1), (rx2, ry2), [255, 0, 0], thickness)

# calculate backoff from intercept for left line

if lslope < leftslopemax and lslope > leftslopemin: # left

ly1 = yi + int(backoff)

lx1 = int(lx2-(ly2-ly1)/lslope)

ly2 = ysize-1

lx2 = int(lx1+(ly2-ly1)/lslope)

cv2.line(img, (lx1, ly1), (lx2, ly2), [255, 0, 0], thickness)

# if we have all of the points - draw the backoff line near the horizon

if lx1 > 0 and ly1 > 0 and rx1 > 0 and ry1 > 0:

cv2.line(img, (lx1, ly1), (rx1, ry1), [255, 0, 0], thickness)

# return the left and right line slope, found rectangler box shape and the estimated vanishing point.

return lslope+rslope, lslope, rslope, (lx1,ly1), (rx1,ry1), (rx2, ry2), (lx2, ly2), (xi, yi)

We now have the calculated points: (lx1,ly1), (rx1,ry1), (rx2, ry2) and (lx2, ly2) that we can use as source point for the OpenCV getPerspectiveTransform function, but we still need a destination points for us to warp into. Since our two stated goal outside of the project goals from the beginning is to:

- Extend the rectified lane lines as far to the horizon as possible

- Keep the correct aspect ratio when projecting the perspective view down to a planar ('birds-eye') view

It is reasonable that we will want to maintain symmetry as diagrammed earlier, so we came up with this code segment in the ProjectionManager module to help us map the resulting transform:

# normal image size

self.x, self.y = self.img_size

# generate destination rect for projection of road to flat plane

us_lane_width=12 # US highway width: 12 feet wide

approx_dest=20 # Approximate distance to vanishing point from end of rectangle

scale_factor=15 # scaling for display

top=approx_dest*scale_factor

left=-us_lane_width/2*scale_factor

right=us_lane_width/2*scale_factor

self.curDstRoadCorners = np.float32([[(self.x/2)+left,top],[(self.x/2)+right,top],[(self.x/2)+right,self.y],[(self.x/2)+left,self.y]])

Using these calculated source and destination rectangles, we are now able to perform the perspective transform in ProjectManager unwarp_lane function:

# function to project the undistorted camera image to a plane looking down.

def unwarp_lane(self, img, src, dst, mtx):

# Pass in your image, 4 source points src = np.float32([[,],[,],[,],[,]])

# and 4 destination points dst = np.float32([[,],[,],[,],[,]])

# Note: you could pick any four of the detected corners

# as long as those four corners define a rectangle

# One especially smart way to do this would be to use four well-chosen

# use cv2.getPerspectiveTransform() to get M, the transform matrix

# use cv2.warpPerspective() to warp your image to a top-down view

M = cv2.getPerspectiveTransform(src, dst)

img_size = (img.shape[1], img.shape[0])

warped = cv2.warpPerspective(img, M, img_size, flags=cv2.INTER_LINEAR)

# warped = gray

return warped, M

This function when applied to the test images, has the following outcome when using the last Jupyter notebook version:

NOTE: We were not able to perform two of the perspective transform in the set of test images below. This is because we were unable to find an estimated lane line in two of the video frames in the harder challenge video where the right lane line became obscured or nearly vertical. These are just two of the many failure points in our current, even CLI, implementation.

But as explained earlier, we had some versioning issues with the Jupyter notebook and that was abandoned, but wanted to show what was working up to that point. In the newer CLI implementation of the software pipeline, you may generate a diagnostic screen of the image perspective projection using the following syntax:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=2 <inputfile> <outputfile>

The following sample run:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=2 test_images/test5.jpg output_images/test5diag2.jpg

Produces this output:

To understand perspective images, you have to understand what is the vanishing point. The vanishing point is formed by where the two estimated red lane lines meet with the yellow horizon line in the perspective image above in the upper-left panel. It is important to realize that when we did the transform, we effectively stretched the pixels near the vanishing point to fit the top of our new planar 'birds-eye' view, while at the same time compressed the pixels near the bottom of our perspective image. To understand this stretching effect better, we drew a dark green hexagon in the perspective image, and then projected it onto the planar 'birds-eye' view in the lower-left panel. Notice how the bottom of the hexagon is now much smaller in the birds-eye view than in the perspective image? What about the top of the hexagon? The sides of the two longer sides of the hexagon are now parallel in the 'birds-eye' view. What kind of stretching do you think are involved? Also, notice how far to the top that the concrete bridge ends in the perspective image, but it seem quite short in comparison in the planar birds-eye view? What's happening there?

This is all done inline to keep the birds-eye view aspect ratio correct as one of our stated goals. This can be seen from the clearer more defined details of the concrete bridge as compared to the rest of birds-eye image. It is important to keep in mind that the perspective transform is non-linear, especially near the horizon and particularly at the vanishing point. What this means is that as you go closer and closer to the horizon/vanishing point in the perspective image, things are going farther and farther away. This become quite non-intuitive in that what we assume is quite near, is often quite far away. This particular article should shed some light on this subject: Slow Down, Those lane lines are longer than you think!

Since we have compress the pixels at the bottom of the new birds-eye view image, it is reasonable to hypothesize that more accurate lane line information is there as well. Especially since the source points for the transformation was the estimated lane lines themselves. To indicate this, we drew two parallel red lines from the bottom of the birds-eye image to near where the backoff points should be. Those two red parallel lines are, in essence, the initial lane line estimates, so we will start from there in the next section.

Now that we have transformed our perspective view to a planar 'birds-eye' view, its time to identify the lane lines on the road surface. We could just start by using the lane line estimates that we used for projection in the first place, but what is the fun in that? Instead, we will go ahead and use a histogram of the lane lines that we have already isolated using our ImageFilter module.

What we will do is to sum the pixels columns and whatever pixel location has the highest sum will be where the lane line will start. To make this more weighted towards the bottom of the 'birds-eye' image, we will only take the sum of the bottom half of the image. In the new CLI implementation, this function is now controlled by the RoadManager module's find_lane_locations function. Here is its implementation:

# function to find starting lane line positions

# return left and right column positions

def find_lane_locations(self, projected_masked_lines):

height = projected_masked_lines.shape[0]

width = projected_masked_lines.shape[1]

lefthistogram = np.sum(projected_masked_lines[int(height/2):height,0:int(width/2)], axis=0).astype(np.float32)

righthistogram = np.sum(projected_masked_lines[int(height/2):height,int(width/2):width], axis=0).astype(np.float32)

leftpos = np.argmax(lefthistogram)

rightpos = np.argmax(righthistogram)+int(width/2)

# print("leftpos",leftpos,"rightpos",rightpos)

return leftpos, rightpos, rightpos-leftpos

NOTE: We know there are some assumptions made here about the starting location of the left and right lane lines being in their respective quadrants (III and IV); howerver, besides the harder challenge video, this model fits the normal cases. So to keep this implementation simple, we will leave it as is for this phase of development.

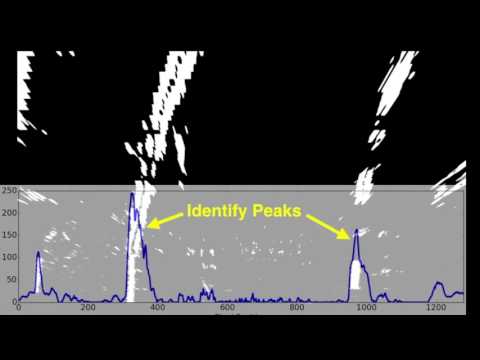

The results of the histogram should be something like this when graphed:

At the end of the histogram sumation, we will take the argmax of the different quadrants and use the computed column location for the base of the lane lines location.

Using the computed Lane Line base column positions as the start, we can now use a technique to 'walk up' the lane lines. The idea is to 'walking up' the lane lines by iteratively taking the histograms of the binary 'birds-eye' view image, section by section until the complete lane lines are found. Below is a video of this concept:

The implementation of this algorithm is handled by the Line module in the find_lane_nearest_neighbors and find_lane_lines_points functions. The find_lane_lines_points function will call find_lane_nearest_neighbors iteratively to calculate histograms of the lane line as it moves up the image. But, unlike before, we will not be using argmax to compute an exact point or column position, but instead add each point we found into a pair of X,Y arrays for later processing:

# function to find lane line positions given histogram row, last column positions and n_neighbors

# return column positions

def find_lane_nearest_neighbors(self, histogram, lastpos, nneighbors):

ncol = len(histogram)-1

x = []

list = {"count":0, "position":lastpos}

for i in range(nneighbors):

if (lastpos+i) < len(histogram) and histogram[lastpos+i] > 0:

x.append(lastpos+i)

if list['count'] < histogram[lastpos+i]:

list['count'] = histogram[lastpos+i]

list['position'] = lastpos+i

if (lastpos-i) > 0 and histogram[lastpos-i] > 0:

x.append(lastpos-i)

if list['count'] < histogram[lastpos-i]:

list['count'] = histogram[lastpos-i]

list['position'] = lastpos-i

return list['position'], x

# function to set base position

def setBasePos(self, basePos):

self.pixelBasePos = basePos

# function to find lane lines points using a sliding window histogram given starting position

# return arrays x and y positions

def find_lane_lines_points(self, masked_lines):

xval = []

yval = []

nrows = masked_lines.shape[0] - 1

neighbors = 12

pos1 = self.pixelBasePos

start_row = nrows-16

for i in range(int((nrows/neighbors))):

histogram = np.sum(masked_lines[start_row+10:start_row+26,:], axis=0).astype(np.uint8)

pos2, x = self.find_lane_nearest_neighbors(histogram, pos1, int(neighbors*1.3))

y = start_row + neighbors

for i in range(len(x)):

xval.append(x[i])

yval.append(y)

start_row -= neighbors

pos1 = pos2

self.allX = np.array(xval)

self.allY = np.array(yval)

In addition, since the Line module is instantiated twice, one for each left and right lane lines, the find_lane_lines_points will also have to be called twice by the RoadManager module, once for each left and right lanes lines.

Once we found the points associated with the lane line, we need to be able to fit it into a 2nd degree polynomial in the form:

x = Ay^2 + By + C

Where A, B and C are polynomial coefficient constants returned by numpy polyfit() function. This may seem non-intuitive, but, from the equation's perspective, we are looking at the road from its side rotated 90 degrees from its base. Here is an example of what this looks like with the fitting polynomial drawn on top, red is the left lane and blue is the right lane:

And here is the relevant code segment in the Line module:

# Fit a (default=second order) polynomial to lane line

# Use for initialization when first starting up or when lane line was lost and starting over.

def fitpoly(self, degree=2):

if len(self.allY) > 150:

# We need to increase our pixel count by 2 to get to 100% confidence.

# and maintain the current pixel count to keep the line detection

self.confidence_based = len(self.allY)*2

self.confidence = len(self.allY)/self.confidence_based

self.detected = True

self.currentFit = np.polyfit(self.allY, self.allX, degree)

polynomial = np.poly1d(self.currentFit)

self.currentX = polynomial(self.allY)

# create linepoly

xy1 = np.column_stack((self.currentX+30, self.allY)).astype(np.int32)

xy2 = np.column_stack((self.currentX-30, self.allY)).astype(np.int32)

self.linePoly = np.concatenate((xy1, xy2[::-1]), axis=0)

# create mask

self.linemask = np.zeros_like(self.linemask)

cv2.fillConvexPoly(self.linemask, self.linePoly, 64)

## Add the point at the bottom.

## NOTE: we walked up from the bottom - so the base point should be the first point.

allY = np.insert(self.allY, 0, self.y-1)

allX = polynomial(allY)

self.XYPolyline = np.column_stack((allX, allY)).astype(np.int32)

# create the accumulator

self.bestFit = self.currentFit

You may have notice that there are gaps between the detected lane lines points and wonder why not all of points are accounted. The Line module's find_lane_nearest_neighbors and find_lane_line_points algorithms actually want to have gaps in between for two reasons:

- Faster: Less point counting means less time spent processing.

- Allow for increase confidence in subsequent frame processing

What this means is that since we are optimizing on speed, the less time we spend on processing each frame matters. Counting just half the lane line points is good enough for when we initialize the Line module. Especially if it needs to do this in the middle of the video when a faster line-tracking algorithm has a miss and needs to start over (see section 3.3.2 Lane Tracking for further discussion). In addition, we are assuming only half the points were counted in our confidence lane line detection algorithm (see section 3.3.3 Confidence Calculations)

Getting the line measurements out was the most difficult part of project 4. In particular, since we wanted to have both a correct aspect ratio of the 'birds-eye' view and being able to project as far into the horizon as possible, this makes calculating the length of the road in the 'birds-eye' view difficult, since distance near the vanishing point as explained earlier may not be deterministic.

Then a fellow student, Kyle Stewart-Frantz, came forward with information that were not available before, the actual location of where the video was taken and an estimate of what the radius of curvature of the road at frame 93 of the project video. Here is the location as drawn on Google Map with the approximate radius curvature in meters:

From the reviewer, it seems that the first curve should have an estimated radius of curvature about 900m (+/- 20m error). Looking at my model and projection calculations, I was not quite sure how to resolve the differences, until I found US Department of Transportation's Federal Highway Administration's guidelines on Width and Patterns of Longitudinal Pavement Markings (Section 3A.05.) In the guidelines it states: "Broken lines should consist of 3 m (10 ft) line segments and 9 m (30 ft) gaps, or dimensions in a similar ratio of line segments to gaps as appropriate for traffic speeds and need for delineation." So, that mean one set of line and the gap between the lines together should be 12 m in length. Going back into the projection, we try to find a location nearly straight and start taking some measurements in the 'birds-eye' view. Frame 338 fit the description and is shown below:

And here is another from frame 362:

After taking some measurements from both frames, we believe the Y projected distance is approximately 52 meters instead of the assumed 30 meters, but we want to caution that this may just be a at this particular location. Due to the dynamic nature of the environment where the road horizon rises and falls, the projected distance may change at anytime and may not be predictable at this close to the vanishing point. However, even though this is a rough approximation, it is a better one than the 30 meters that we started with. Once we updated the Line module's radius_in_meters function with the new 52 meters value:

# Define conversions in x and y from pixels space to meters given lane line separation in pixels

# NOTE: Only do calculation if it make sense - otherwise give previous answer.

def radius_in_meters(self, distance):

if len(self.allY) > 0 and len(self.currentX) > 0 and len(self.allY) == len(self.currentX):

#######################################################################################################

# Note: We are using 54 instead of 30 here since our throw for the perspective transform is much longer

# We estimate our throw is 54 meters based on US Highway reecommended guides for Longitudinal

# Pavement Markings. See: http://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/htm/2003r1/part3/part3a.htm

# Section 3A.05 Widths and Patterns of Longitudinal Pavement Markings

# Guidance:

# Broken lines should consist of 3 m (10 ft) line segments and 9 m (30 ft) gaps,

# or dimensions in a similar ratio of line segments to gaps as appropriate for

# traffic speeds and need for delineation.

# We are detecting about 4 and 1/3 sets of dashed line lanes on the right side:

# 4.33x(3+9)=4.33x12=52m

########################################################################################################

ym_per_pix = 52/720 # meters per pixel in y dimension

xm_per_pix = 3.7/distance # meteres per pixel in x dimension (at the base)

#

# Use the middle point in the distance of the road instead of the base where the car is at

ypoint = self.y/2

fit_cr = np.polyfit(self.allY*ym_per_pix, self.currentX*xm_per_pix, 2)

self.radiusOfCurvature = ((1 + (2*fit_cr[0]*ypoint + fit_cr[1])**2)**1.5)/(2*fit_cr[0])

return self.radiusOfCurvature

Our RoadManager averages the left and right lane line measurements:

self.radiusOfCurvature = (self.leftLane.radiusOfCurvature + self.rightLane.radiusOfCurvature)/2.0

And we end up with 896.388019m measurement at the first curve at frame 93 (Full Diagnostics):

And here is frame 93 in its final form:

In addition, whenever the left and right lane lines are observed to be nearly straight, we will state this instead of giving a bad radius of curvature measurement. An example of this is shown below:

Here we are asked to measure the position of the vehicle with respect to the lane lines. If the vehicle is equal distance away from both the left and right, then it is centered. If the vehicle is shorter distance away from the left lane than the right lane, then it is left of center. If it shorter distance away from the right lane than the left lane, then it is right of center. When a particular lane is shorter distance away, we can measure is shorter distance to the middle of the vehicle and use that as the positioning measurement. We use the Line module's meters_from_center_of_vehicle function to measure each lanes distance away from the vehicle's center.

# Define conversion in x off center from pixel space to meters given lane line separation in pixels

def meters_from_center_of_vehicle(self, distance):

xm_per_pix = 3.7/distance # meteres per pixel in x dimension given lane line separation in pixels

pixels_off_center = int(self.pixelBasePos - (self.x/2))

self.lineBasePos = xm_per_pix * pixels_off_center

return self.lineBasePos

We have to pass in a distance parameter, since we may not be able to predict how far apart in pixel space the lane lines could be in the 'birds-eye' view. It is up to RoadManager to calculate this measurement and send it to the meters_from_center_of_vehicle function as shown in the code segment below:

# take and calculate some measurements

distance = self.rightLane.pixelBasePos - self.leftLane.pixelBasePos

self.leftLane.radius_in_meters(distance)

self.leftLane.meters_from_center_of_vehicle(distance)

self.rightLane.radius_in_meters(distance)

self.rightLane.meters_from_center_of_vehicle(distance)

It is here that I like to thank Kyle Stewart-Frantz again. It was he that pointed out that my meter to centimeter conversion was off by a factor of 10! Thanks again Kyle!

After all of this processing, the software pipeline now needs to somehow show that it was able to identify the lane lines. The best way to do this is to somehow paint the image of where the lane lines are and their boundaries. Since we fitted a polynomial equation to describe the line, we can use it to create the points necessary to draw a polygon of the surface of the road. The following code segment is what the RoadManager module does to do this with the help of its left and right Line, ImageFilters and ProjectionManager modules:

# create road mask polygon for reprojection back onto perspective view.

roadpoly = np.concatenate((self.rightLane.XYPolyline, self.leftLane.XYPolyline[::-1]), axis=0)

roadmask = np.zeros((self.y, self.x), dtype=np.uint8)

cv2.fillConvexPoly(roadmask, roadpoly, 64)

self.roadsurface[:,:,0] = self.curImgFtr.miximg(leftprojection,self.leftLane.linemask, 0.5, 0.3)

self.roadsurface[:,:,1] = roadmask

self.roadsurface[:,:,2] = self.curImgFtr.miximg(rightprojection,self.rightLane.linemask, 0.5, 0.3)

# unwarp the roadsurface

self.roadunwarped = self.projMgr.curUnWarp(self.curImgFtr, self.roadsurface)

# create the final image

self.final = self.curImgFtr.miximg(self.curImgFtr.curImage, self.roadunwarped, 0.95, 0.75)

Below are some results from the Jupyter notebook version before it was abandoned:

NOTE: We were not able to perform at least one of the perspective transform in the set of test images below, and some are poorly done. This is because we were unable to find an estimated lane line in most of the video frames in the harder challenge video where the right lane line became obscured, nearly vertical or hidden by a passing vehicle. These are just three of the many failure points in our current, even CLI, implementation.

You may also use the CLI to display the road mask rendering by invoking the --diag=2 option like so:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=2 test_images/test5.jpg output_images/test5diag2.jpg

This will produces this output:

Enjoy!

As explained in the previous sections, there are diagnostics screen available from the DiagManager to help you with any errors you see happening and see where it may be occuring. If you believe it is an ImageFilter bug, you may want to use the --diag=1 option to invoke the ImageFilter diagnostics as shown here:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=1 test_images/test1.jpg output_images/test1diag1.jpg

will produce this image:

If you believe it is a ProjectionManager bug, you may want to use the --diag=2 option to invoke the ProjectionManager diagnostics as shown here:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=2 test_images/test1.jpg output_images/test1diag2.jpg

will produce this image:

If you believe it is a RoadManager or Line module bug, you may want to use the --diag=3 option to invoke the Full Diagnotics Mode as shown here:

python P4pipeline.py --diag=3 test_images/test1.jpg output_images/test1diag3.jpg

will produce this image:

Whereas section 3.2 was about processing a single image, this section is about processing video. Both are similar in that we need to identify lane lines; however, when dealing with video, one must be able to process the video, frame by frame, efficiently. This means if the software pipeline finds that the frames are similar, then to build up efficiency, find ways to incorporate its findings to the next frame. This will be the topic in this section.

There are three test videos from Udacity for this section. They are:

- Project Video: This video shows the forward facing view of a multi-lane highway. The road markings are mostly good, with some low contras areas around bridges. The weather conditions are nice and the sky is clear.

- Challenge Video: This video shows the forward facing view of a multi-lane highway. The road markings are faded and the pavements are in need of repair. The weather conditions are nice, but the sky are cloudy.

- Harder Challenge Video: This video shows the forward facing view of a winding two-lane country road. The road markings are good at the beginning, but become poor as there are locations of poor visibility and high and low lit areas as the video continues. The weather is nice, but the environment is in a forest surrounded by trees, which has interesting lighting issues.

For all videos, frame 1 to N initialization is the same, since there are no prior images to pass forward. The software pipeline is essentially performing all of the steps in section 3.2 using the first frame of the video as the single image. This process is also repeated if there is a failure in subsequent lane tracking (see section 3.3.4, Confidence Calculations). Currently, N is set to 2. Examples of first frame initializations are shown below:

Project Video: Frame 1

Challenge Video: Frame 1

Harder Challenge Video: Frame 1

Once we reach the beyond the first N frames then it becomes more interesting. The subsequent frames are still going through the CameraCal module which does the distortion correction mentioned in section 3.2.2 and the ImageFilter module which performs image filtering from section 3.2.3. However, by now the lane tracking should be close to 100% confidence (see section 3.3.4, Confidence Calculations). So, now the ProjectionManager no longer needs to perform its line approximation to find its source points to transform the image from perspective view to 'birds-eye' view mentioned in section 3.2.4. Instead, it will start using the source points as it was discovered when the lane lines reached 100% confidence. As mentioned before, there are hooks for the RoadManager module to tweak the source points based on the apparent vertical location of the horizon and vanishing point as discovered by the ImageFilter module.

# an attempt to dampen the bounce of the car and the road surface.

# called by RoadManager class

def setSrcTop(self, newTop, sideDelta):

if newTop > self.gradient0:

self.ytopbox = newTop-15

self.xtop1 += sideDelta

self.xtop2 -= sideDelta

self.lane_info = (self.lane_info[0], \

self.lane_info[1], \

self.lane_info[2], \

(self.lane_info[3][0]+sideDelta, newTop), \

(self.lane_info[4][0]-sideDelta, newTop), \

self.lane_info[5], \

self.lane_info[6], \

self.lane_info[7])

This ProjectionManager setSrcTop function was an attempt to dampen the bounce of the car and the road surface as detected by a rapid change in the vanishing point; however, we concluded that additional experimentation would need to occur that went beyond the scope of this project and have placed it on hold.

As explained before in section 3.2.5, Lane Line Identification, the first one or two frames went through the exercise of creating histograms and walking up the lanes in the 'birds-eye' view, and then finally fitted a 2nd degree polynomial with the lane lines laying on its sides. Below is a reminder of the image of the road from its side rotated 90 degrees from its base, as an example from section 3.2.5.3 Fitting a 2nd Degree Polynomial:

Again, notice that there are gaps between the discovered lane line points? In the next frame, you will find that these points are now filled:

So, what just happen? How come the 2nd frame was able to more accurately find the lane line points that we had to work hard to find before? Simple really, as part of fitting the 2nd degree polynomial, the Line module also generated a line mask. This line mask is similar to the region of interest that we used before in Project 1, but instead of masking the entire region where the lane lines could be, we are creating a mask using the found lane line in the previous frame 'birds-eye' view and now applying it to the new frame. We are creating this mask using the polynomial we fitted before and creating a polygon by adding an offset to either side. By default it is +/-30 on both sides of the polyline during initialization, but afterwards drops to only +/-5:

# create linepoly

xy1 = np.column_stack((self.currentX+self.maskDelta, self.allY)).astype(np.int32)

xy2 = np.column_stack((self.currentX-self.maskDelta, self.allY)).astype(np.int32)

self.linePoly = np.concatenate((xy1, xy2[::-1]), axis=0)

# create mask

self.linemask = np.zeros_like(self.linemask)

cv2.fillConvexPoly(self.linemask, self.linePoly, 64)

After that the RoadManager module activates this mask at the appropriate time and counts the number of pixel points that is masked, like when the region of interest was applied in Projection 1:

# apply the line masking poly

def applyLineMask(self, img):

#print("img: ", img.shape)

#print("self.linemask: ", self.linemask.shape)

img0 = img[:,:,1]

masked_edge = np.copy(self.linemask).astype(np.uint8)

masked_edge[(masked_edge>0)] = 255

return cv2.bitwise_and(img0, img0, mask=masked_edge)

Remember, these masks are applied by the Line modules individually, so the left lane line has its own mask, and the right lane line has its own mask too. If the lane lines were successfully found, the found points are gathered together and another polynomial is fitted. This polynomial in turn will then create its own polyline and a line mask and the process repeats. Now its time to figure out if we were successful in finding the lane in this frame.

After the masking of the lane line points, the Line module counts the number of pixels were captured by its mask and then calculates its confidence of finding the lane line in this frame. Remember in section 3.2.5.3, Fitting a 2nd Degree Polynomial, we said that we were only counting half of the points? We mention that there were two reasons:

- Faster: Less point counting means less time spent processing

- Allow for increase Confidence in Subsequent frame processing

Speed we already talked about before, since our python script was doing the counting, it was less efficient than if Numby or OpenCV did the job. Now, lets explain why counting half would increase confidence. As explained before, we counted half of the points and then doubled it for the self.confidence_based. This was because we were quite sure that in the subsequent frame, the lane line points would be there to reach double the point count as long as we were accurate in our findings at the beginning. For example, here is the Frame 1 again in the Project Video in the Projection Diagnostics:

Notice that at 50% confidence in frame 1, the confidence level of the left lane line had a count of 600 pixel points, while the right side had a count of 503 pixel points. Now let's look at the frame 2:

Notice that the confidence levels on both lines are now at 100%, since they are capped there. Also notice that the left pixel counts are now at 5477 and the right at 3611. This is an increase by a factor of at least 6X, so should not be a problem. The other thing to notice is that the current frame's lane lines predicted by the last frame were very accurate with hardly any false positives or false negatives. At 10 frames out:

Both Left and right lane line pixel counts have dropped a little. Left is at 5381, and right is at 2147, and confidence is still at 100% for both. At 100 frames out:

Right lane line pixel counts have dropped a little, but the left lane line is now even higher. Left is at 5381, and right is at 2147, and confidence is still at 100% for both. Now how is it counting the pixels, and is it fast? The RoadManager is counting the pixels using Numpy nonzero function to do the counting, using the following code segment:

# Left Lane Projection setup

leftprojection = self.leftLane.applyLineMask(self.curImgFtr.getProjection(self.leftLane.side))

leftPoints = np.nonzero(leftprojection)

self.leftLane.allX = leftPoints[1]

self.leftLane.allY = leftPoints[0]

self.leftLane.fitpoly2()

# Right Lane Projection setup

rightprojection = self.rightLane.applyLineMask(self.curImgFtr.getProjection(self.rightLane.side))

rightPoints = np.nonzero(rightprojection)

self.rightLane.allX = rightPoints[1]

self.rightLane.allY = rightPoints[0]

self.rightLane.fitpoly2()

Looking at this pattern, it seems that this algorithm could sustain itself forever, but all good things must come to an end, so in this section we will discuss what happens when we lose track of the lane lines and how do we recover. For example, the first concrete bridge after the curve has always been a challenge. First it was the yellow lane lines on white concrete background, now we find that it causes the projection to become misaligned, and so the lane lines no longer match for the right lane line. At frame 560, the right lane line finally drops below its 50% threshold at 238 pixel count on the concrete bridge and declares it no longer has confidence in its tracking abilities:

At frame 561, the RoadManger module initiates a complete restart and goes back to the same routine as described in section 3.2.

This in turns sets up a confidence of 50% with a threshold of 716 pixel count for the left lane and 321 pixel count for the right lane. At frame 562, the RoadManager and Line modules attempt to restart the faster process at outlined previously in this section:

And was successful in reaching 100% confidence on both left and right lane lines again, with a pixel count of 8549 for the left lane line and a 2882 pixel count for the right lane. However, the software pipeline was not able to completely recover and suffered another relapse at frame 637, just after passing the bridge:

The thing to notice is that the horizon line and vanishing point have now come too close to the backoff point and we are now mapping a much larger area than we should. In this particular case, its the perspective transform source coordinates at fault and needs to be corrected. In the next frame, as before, the RoadManager and Line modules initiates a complete restart and goes back to the same routine as described in section 3.2 that results in frame 638:

And by frame 639, the left lane pixel count is now back up to 6608 and the right lane line pixel count is at 2086. Confidence is restored at 100% once again, and the process repeats until the end of the video frames is reached.

During this process of analyzing lane line-tracking loss, we used our diagnostics tools to figure why we were failing so often. We actually had a lot more failures before, and our predictions were less accurate. We wanted to find a better way to prevent these failures in the first place while maintaining a more efficient process. In this section, we discussed some failure prevention methods we discovered.

Before putting together our intervention method, we notice that the Line modules only fed their statistics forward to the RoadManager and there were no active feedback mechanism to have the Line module improve its performance by the RoadManager module. So, there were alot of information being gathered by the RoadManager that were not placed into service to accurately predict the lane line locations. We decided to change that.

One of our discovery was that when the Line module loses track of a lane line; it is usually the points towards the horizon that were missed. If we do not actively try to move back up and re-discover the lane line positions, we would lose the lane line completely and have to restart the process. At first we tried different ways for the RoadManager to predict where the roadmarkings were and then force the Line component to search there. This ended in all sorts of interesting lane line patterns that did not necessarily conform to what was actually in the video. What we ended up doing was just to have the RoadManager tell the Line component to go higher, but only a little at a time (ten pixels). It seems this general request was all that was needed because the Line module actually knew what to do using its fitted polynomials. It just needed to be told to extend its lane line mask higher up to encompass the extra points that were missed before. Below are the new code segments added to RoadManager module to enable this:

# If we are in the harder challenge, our visibility is obscured,

# so only do this if we are certain that our visibility is good.

# i.e.: not in the harder challenge!

if self.curImgFtr.visibility > -30:

# if either lines differs by greater than 50 pixel vertically

# we need to request the shorter line to go higher.

if abs(self.leftLaneLastTop[1]-self.rightLaneLastTop[1])>50:

if self.leftLaneLastTop[1] > self.rightLaneLastTop[1]:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(self.rightLaneLastTop[1])

else:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(self.leftLaneLastTop[1])

# if our lane line has fallen to below our threshold, get it to come back up

# but only move up 10 pixels at a time.

if leftTop is not None and leftTop[1]>self.mid-100:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(leftTop[1]-10)

if leftTop is not None and leftTop[1]>self.leftLaneLastTop[1]:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(leftTop[1]-10)

if rightTop is not None and rightTop[1]>self.mid-100:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(rightTop[1]-10)

if rightTop is not None and rightTop[1]>self.rightLaneLastTop[1]:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(rightTop[1]-10)

# visibility poor...

# harder challenge... need to be less agressive going back up the lane...

# let at least 30 frame pass before trying to move forward.

elif self.curFrame > 30:

# if either lines differs by greater than 50 pixel vertically

# we need to request the shorter line to go higher.

if abs(self.leftLaneLastTop[1]-self.rightLaneLastTop[1])>50:

if self.leftLaneLastTop[1] > self.rightLaneLastTop[1] and leftTop is not None:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(leftTop[1]-10)

elif rightTop is not None:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(rightTop[1]-10)

# if our lane line has fallen to below our threshold, get it to come back up

# but only move up 10 pixels at a time.

if leftTop is not None and leftTop[1]>self.mid+100:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(leftTop[1]-10)

if leftTop is not None and leftTop[1]>self.leftLaneLastTop[1]:

self.leftLane.requestTopY(leftTop[1]-10)

if rightTop is not None and rightTop[1]>self.mid+100:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(rightTop[1]-10)

if rightTop is not None and rightTop[1]>self.rightLaneLastTop[1]:

self.rightLane.requestTopY(rightTop[1]-10)

You may have noticed that we split up how the RoadManager behaves based on detected visibility score from the ImageFilter. This is because during low visibility conditions, the road horizon may be a very short distance away, and we should not aggressively climb back up the lane lines in case they are not there!

When we put in the code segment to request for a movement in the Line module's polyline length, we needed an interface to have the Line module respond to this request. We decided that the response for these requests should happen in the next frame, since trying to do everything in the current frame would slow things down, and have unpredictable results, so we added a new Line module requestTopY function.

# road manager request to move the line detection higher

# otherwise the algorithm is lazy and will lose the entire line.

def requestTopY(self, newY):

self.newYTop = newY

This function sets a new request into the Line module for a new top for its polynomial to reach. In the next frame, the Line module respond by adding the requested point to its allY and calculates its corresponding X point:

# honoring the road manager request to move higher

## NOTE: these points are counted by numpy - it does topdown, so our top point

## is now at the front of the list.

if self.newYTop is not None:

x = polynomial([self.newYTop])

self.allY = np.insert(self.allY, 0, self.newYTop)

self.allX = np.insert(self.allX, 0, x[0])

self.newYTop = None

So, what does this behavior look like in practice? This animated GIF file shows the answer. After a partial lane line miss, the RoadManager will start requesting the lane lines to climb higher, and we see this walking up the lane effect.

As explained earlier, the project video shows the forward facing view of a multi-lane highway. The road markings are mostly good, with some problems at the low contras areas around bridges. The weather conditions are nice and the sky is clear.

This video is mostly clean and the problem areas are isolated to the bridges. The CLI software pipeline is able to handle the video easily with just three restarts at frames: 199, 561 and 638.

At frame 198 in the project video, we find that there the right lane was unable to keep track of the dashed line pavement marking while it curved and dropped to only 443 pixel counts, which was below 50% confidence.

At frame 199, the RoadManager module initiates a complete restart and goes back to the same routine as described in section 3.2. This in turns sets up a confidence of 50% with a threshold of 728 pixel count minimum for the left lane line and 609 pixel count minimum for the right lane line.

At frame 200, the RoadManager and Line modules attempt to restart the faster process as discussed in detail previously in section 3.3.5, Losing Track and Recovery:

The recovery was successful with confidence restored to 100% for both left and right lane lines and with high pixel counts of 6865 and 5242 respectively. This issue may be resolvable with the increase the width of the line mask by increasing the self.maskDelta from 5 to perhaps 12; however, this may introduce false positive pixel masking, something to look into in the future.

At frame 560 in the project video, we find that there was a jarring bounce that caused the projection to become misaligned, and so the lane lines no longer match for the right lane line. Notice that the top of the 'birds-eye' view of the lane lines is much wider apart than at the bottom. At frame 560, the right lane line finally drops below its 50% threshold at 238 pixel count on the concrete bridge and declares it no longer has confidence in its tracking abilities:

At frame 561, the RoadManger module initiates a complete restart and goes back to the same routine as described in section 3.2.

This in turns sets up a confidence of 50% with a threshold of 716 pixel count for the left lane and 321 pixel count for the right lane. At frame 562, the RoadManager and Line modules attempt to restart the faster process as discussed in detail previously in section 3.3.5, Losing Track and Recovery:

And was successful in reaching 100% confidence on both left and right lane lines again, with a pixel count of 8549 for the left lane line and a 2882 pixel count for the right lane.

However, the software pipeline was not able to completely recover from the bounce experienced at frame 561, and suffered another relaps at frame 637, just after passing the bridge:

The thing to notice is that the horizon line and vanishing point have now come too close to the backoff point and we are now mapping a much larger area than we should. In this particular case, its the perspective transform source coordinates at fault and needs to be corrected. In the next frame, as before, the RoadManager and Line modules initiates a complete restart and goes back to the same routine as described in section 3.2 that results in frame 638: