Project Lead: Mateo Umaguing

Project Scientists: Avantika Aggarwal, Hanna Boughanem, Paige Lee, Sree Nagaraj, Srivarsha Rayasam, Anish Thalamati

Mechanical Engineer: Audrey Ngai

Developed @ CruX UCLA, Neurotech Organization under guidance from Darren Vawter

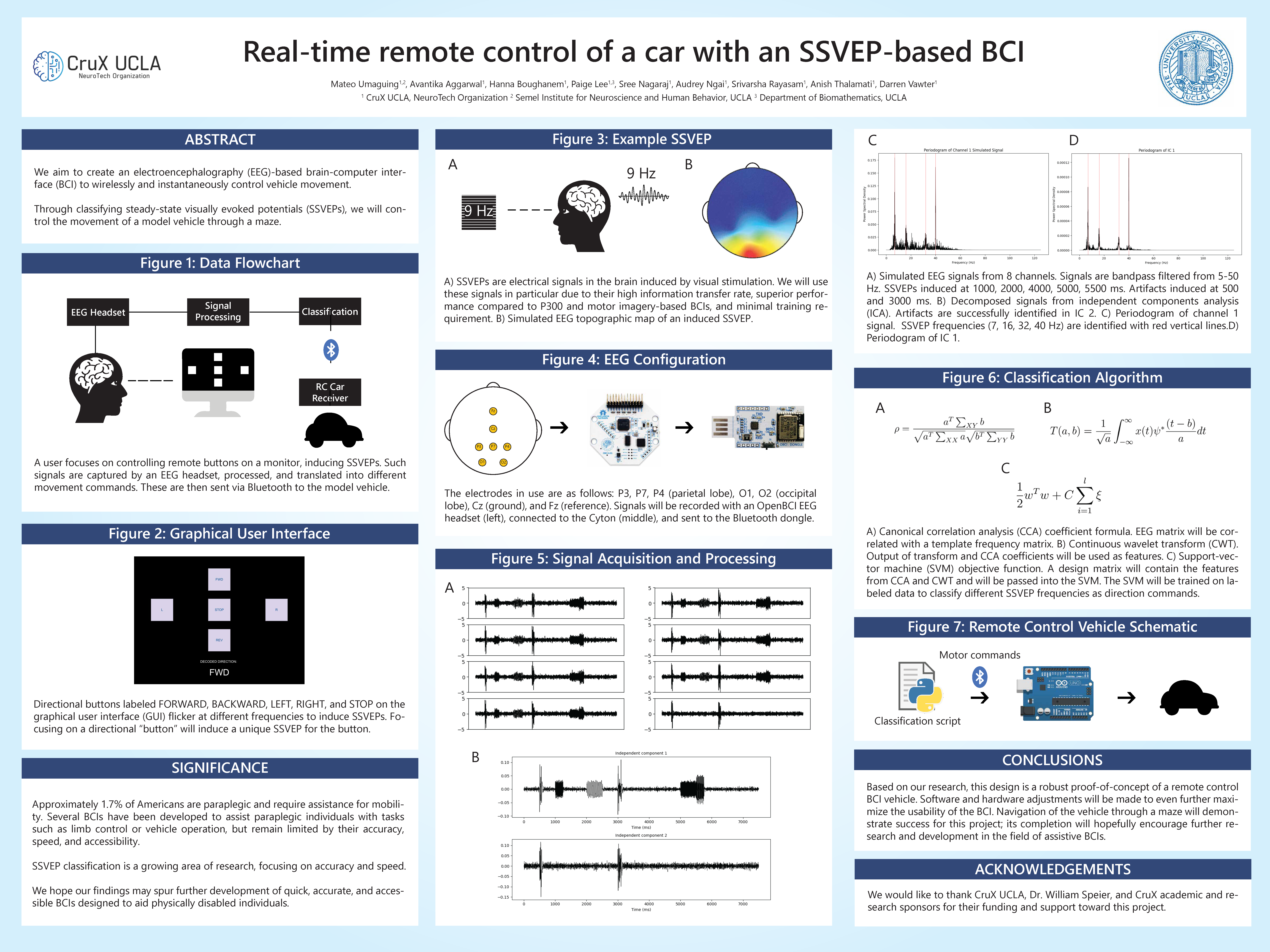

This project aims to design a model car that can be controlled by the brain to navigate through a maze. We will use an OpenBCI EEG headset to collect EEG signals. There are five direction-related buttons with varying flickering frequencies that users may focus on to move the car. So, we will specifically be collecting steady state visually evoked potentials (SSVEP) signals in response to these visual stimuli. After signal processing and feature extraction, we will train and test various machine learning models along with analytical methods to identify which method/model produces the most accurate classifications of SSVEP signals that correspond to the buttons. Lastly, we will implement our selected model and program the car to receive online signals to move through the maze according to the user’s desired directions.

The overall aim of this project is to develop a brain-computer interface (BCI) that can control the movement of a model car.

- Successfully collect EEG signals from the scalp of a participant via OpenBCI headsets.

- Classify steady-state visual-evoked potential (SSVEP) signals using analytical or ML methods.

- Navigate a model car that can successfully respond to the neural signals acquired from an EEG headset through a maze. Significance

- The purpose of this project is to design a model car that can be controlled by the brain rather than motor skills. This is important for paralyzed people, particularly for improving wheelchair design or real cars that they can drive.

- If the car we design can successfully navigate a maze, this will be a significant development because a maze-like environment may be similar to everyday environments that paralyzed people need to navigate in wheelchairs. It won’t likely be similar enough to real-world traffic scenarios, but modifications to adapt this toward traffic scenarios are a possible future direction.

- The experiment will be divided into 3 parts: EEG setup, direction classifier training, and online remote car control.

Fig. 1 - Data Flow Diagram

Schematic displaying the direction and destinations of data in this BCI.

- EEG is configured and fitted on a participant.

- OpenBCI headset is placed on the participant.

- OpenBCI is connected to Cyton, which is connected to the computer.

- Electrodes are gelled to reduce impedance.

- OpenBCI EEG signals are verified through the OpenBCI GUI. Settings within the GUI will be configured in multiple preliminary sessions to maximize signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

- Noisy EEG signals are delivered from the OpenBCI GUI to a Python signal processing script via the lab streaming layer (LSL) system.

- Electrodes of interest are those around the occipital and parietal lobes (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2 - Electrodes Channels of Interest

Available electrodes on the OpenBCI headset are colored. The parietal and occipital electrodes are of interest and are colored in green.

- Signals are passed through a bandpass filter (5-50 Hz) and a notch filter (60 Hz) to remove artifacts. Digital filtering can be accomplished using the OpenBCI GUI and Python (scipy) signal processing toolboxes.

- Independent components analysis will be conducted to remove artifacts.

- Signals are segmented into segments consisting of the last 2 s (this value can be experimentally verified) received from the Cyton for processing.

- Features are extracted from the epochs, primarily in the frequency domain.

- Potential features: mean, variance, max and min values, kurtosis

- Power Spectral Density (in units of watts per Hertz) describes how the power of a particular signal is distributed over different frequencies.

- Local Neighborhood Difference Pattern (LNDP)

- One-Dimensional Local Gradient Pattern (1D-LGP)

- Processed features are then sent to the direction classifier for training/classification.

Fig. 3 - Graphical User Interface

Each button flickers at a different frequency and the bottom text indicates what the decoder is currently detecting.

- The participant is directed to look at a GUI with car direction buttons, a decoded direction indicator, and a live video feed from the car.

- Baseline signal values are recorded while the participant looks at the screen, but not the buttons. These will be signals in which button signals can be compared with to detect when to send commands.

- Buttons will be flickering at 7 Hz, 9 Hz, 11 Hz, 13 Hz, 17 Hz. These values were selected according to past SSVEP-based experiments.

Fig 4. - Training Session Example

During designated segments, the participant will be directed to focus their attention at one of the buttons. The time will be recorded to label parts of the signal according to which button the participant is looking at. Artifacts (i.e. blinks, EMGs) will be induced in order to test artifact removal and to synchronize the time with the labels.

- During several training sessions, the participant will be directed to look at each of the different buttons with differing flickering frequencies in discrete time segments. Differentiated SSVEPs will be captured from the participant looking at the buttons.

- Segments of time within the training session in which the participant is not looking at a button will be designated as “baseline” or rest periods when the car will not move.

- Data from these sessions will be temporally labeled according to which button the participant is looking at during a given time. This will yield labeled data to train the classifiers on.

- Canonical correlation analysis (CCA) will be first implemented as an analytical way to decipher which button is being focused on as used in Ma, Pengfei et al. 2022. This can then be used to extract features for training a ML classifier.

- The continuous wavelet transform has also been used in conjunction with CCA for feature extraction.

- Different classifiers such as support vector machines (SVM) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) will be trained using the labeled data to identify which button the participant is looking at in a given epoch.

- Classifiers will be assessed through F1-scores and cross validation accuracy (Fig. 5).

- We prefer a classifier with low computing time to minimize latency between SSVEP identification and car movement.

Fig. 5 - Simulated Classifier Accuracy and F1 Scores

Different classifiers will be used to decode the EEG signals and will be assessed using various machine learning metrics. The best performing classifier will be used for car navigation.

Fig. 6 - SSVEP Classification Schematic

Detailed flow of data and information from the LSL to the BT receiver on the RC car.

- In another session, the participant is fitted with the EEG headset. The EEG signals are streamed directly to the now trained classifier.

- The participant will look at a given flickering button, and in real-time the classifier will decode which button is being looked at.

- The classifier will then send direction signals (one of LEFT, FWD, RIGHT, REV, STOP) corresponding to the decoded neural signals via Bluetooth to the car. The car will be constructed using Arduino hardware and receive signals through a HC-05 Bluetooth module.

- Once the user “presses” a button, the car will move in the indicated direction until the user focuses their attention onto the “STOP” button.

- The participant, periodically glancing at the car and its position, will attempt to navigate a maze.

Amareswar, Enjeti, et al. “Design of Brain Controlled Robotic Car Using Raspberry Pi.” 2021 5th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/icoei51242.2021.9452957. Hongtao Wang, et al. “Remote Control of an Electrical Car with SSVEP-Based BCI.” 2010 IEEE International Conference on Information Theory and Information Security, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1109/icitis.2010.5689710. Hu , Li. Chapter 2 EEG: Neural Basis and Measurement - Springer. Edited by Zhiguo Zhang, Springer, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/978-981-13-9113-2_2.pdf. Ma, Pengfei, et al. “A classification algorithm of an SSVEP brain-Computer interface based on CCA fusion wavelet coefficients.” Journal of Neuroscience Methods, vol. 371, 1 April 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2022.109502 Rashid, Mamunur, et al. “Current Status, Challenges, and Possible Solutions of EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interface: A Comprehensive Review.” Frontiers in Neurorobotics, vol. 14, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbot.2020.00025. Wang, Hongtao, et al. “The Control of a Virtual Automatic Car Based on Multiple Patterns of Motor Imagery BCI.” Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing, vol. 57, no. 1, 2018, pp. 299–309., https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-018-1883-3. Yu, Yang. “Toward Brain-Actuated Car Applications: Self-Paced Control with a Motor Imagery-Based Brain-Computer Interface.” ScienceDirect, 25 Feb. 2016, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0010482516302074?via%3Dihub. Zhao, QiBin, et al. “EEG-Based Asynchronous BCI Control of a Car in 3D Virtual Reality Environments.” Chinese Science Bulletin, vol. 54, no. 1, 2009, pp. 78–87., https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-008-0547-3.