Table of Contents generated with DocToc

- Setup

- Running Jupyter notebooks

- Variables and Assignment

- Data Types and Type Conversion

- Built-in Functions and Help

- Conditionals

- Lists

- For Loops

- Dictionaries

- Writing functions

- Variable scope

- If we have time

- Libraries

- Virtual environments and packaging

- Numpy

- Plotting with matplotlib

- Multidimensional labeled arrays and datasets with xarray

- Data array: simple example from scratch

- Subsetting arrays

- Plotting

- Vectorized operations

- Split your data into multiple independent groups

- Dataset: simple example from scratch

- Time series data

- Adhering to climate and forecast (CF) NetCDF convention in spherical geometry

- Working with atmospheric data

- Plotting with cartopy

- Working with ocean data

- Running Python scripts from the command line

- Basics of object-oriented programming in Python

- Programming Style and Wrap-Up

- Other advanced Python topics

These notes started few years ago from the official SWC lesson http://swcarpentry.github.io/python-novice-gapminder, but then evolved quite a bit to include other topics. You can find these notes at http://bit.ly/wgeccc.

| instructor | students |

|---|---|

| (1) log in to socrative.com as a teacher | (1) log in to socrative.com as a student |

| (2) start a quiz, select 'python quiz' | (2) enter provided room name |

| (3) select 'teacher paced' | |

| (4) disable student names | |

| (5) start |

| Python pros | Python cons |

|---|---|

| elegant scripting language | slow (interpreted, dynamically typed) |

| powerful, compact constructs for many tasks | |

| very popular across all fields | |

| huge number of external libraries |

Python programs are plain text files, stored with the .py extension.

Many ways to run Python commands:

- from the inside a Unix shell can start a Python shell and type commands

- running Python scripts saved in *.py files

- from Jupyter (formerly iPython) notebooks - stored as JSON files, displayed as HTML

Today we will use a Jupyter notebook. You have several options:

- if you have a university computer ID, go to https://syzygy.ca and under Launch select your institution, then fill in your credentials

- if you have a Google account, go to https://syzygy.ca and under Launch select either Cybera or PIMS, then log in

- if you have a GitHub account, go to https://westgrid.syzygy.ca

- if you have Python+Jupyter installed locally on your machine, then you can start it locally from your shell by typing

jupyter notebook; you will need the following Python packages installed on your computer: numpy, networkx, pandas, scikit-image, matplotlib, xarray, nc-time-axis, cartopy, netcdf (for reading/writing NetCDF files)

This will open a browser page pointing to the Jupyter server (remote except for the last option). Click on New -> Python 3. Explain: tab completion, annotating code, displaying figures inside the notebook.

- Esc - leave the cell (border becomes blue) to the control mode

- "A" - insert a cell above the current cell

- "B" - insert a cell below the current cell

- "X" - delete the current cell

- "M" - turn the current cell into the markdown cell

- "H" - to display help

- Enter - re-enter the cell (border becomes green) from the control mode

- can enter Latex equations in a markdown cell, e.g.

$int_0^\infty f(x)dx$

print(1/2) # to run all commands in the cell, either use the Run button, or press shift+return

- possible names for variables

- don't use built-in function names for variables, e.g. declaring sum won't let you use sum(), same for print

- Python is case-sensitive

age = 100

firstName = 'Jason'

print(firstName, 'is', age, 'years old')

a = 1; b = 2 # can use ; to separate multiple commands in one line

a, b = 1, 2 # assign variables in a tuple notation; same as last line

a = b = 10 # assign a value to multiple variables at the same time

b = "now I am a string" # variables can change their type on the fly

- variables persist between cells

- variables must be defined before use

- variables can be used in calculations

age = age + 3 # another syntax: age += 3

print('age in three years:', age)

Quiz 1: predicting values

With simple variables in Python, assigning var2 = var1 will create a new object in memory var2. Here we have two

distinct objects in memory: initial and position.

Note: With more complex objects, its name could be a pointer. E.g. when we study lists, we'll see that

initialandnewbelow really point to the same list in memory:initial = [1,2,3] new = initial # create a pointer to the same object initial.append(4) # change the original list to [1, 2, 3, 4] print(new) # [1, 2, 3, 4] new = initial[:] # one way to create a new object in memory import copy new = copy.deepcopy(initial) # another way to create a new object in memory

Use square brackets to get a substring:

element = 'helium'

print(element[0]) # single character

print(element[0:3]) # a substring

Quiz 2: getting the second digit of a number (not a string!)

- python is case-sensitive

- use meaningful variable names

print(type(52))

print(type(52.))

print(type('52'))

print(name+' Smith') # can add strings

print(name*10) # can replicate strings by mutliplying by a number

print(len(name)) # strings have lengths

print(1+'a') # cannot add strings and numbers

print(str(1)+'a') # this works

print(1+int('2')) # this works

- Python comes with a number of built-in functions

- a function may take zero or more arguments

print('hello')

print()

print(max(1,2,3,10))

print(min(5,2,10))

print(min('a', 'A', '0')) # works with characters, the order is (0-9, A-Z, a-z)

print(max(1, 'a')) # can't compare these

round(3.712) # to the nearest integer

round(3.712, 1) # can specify the number of decimal places

help(round)

round? # Jupyter Notebook's additional syntax

- every function returns something, whether it is a variable or None

result = print('example')

print('result of print is', result) # what happened here? Answer: print returns None

Python implements conditionals via if, elif (short for "else if") and else. Use an if statement to control whether some block of code is executed or not.

mass = 3.54

if mass > 3.0:

print(mass, 'is large')

Let's modify the mass:

mass = 2.07

if mass > 3.0:

print (mass, 'is large')

Add an else statement:

mass = 2.07

if mass > 3.0:

print(mass, 'is large')

else:

print(mass, 'is small')

Add an elif statement:

x = 5

if x > 0:

print(x, 'is positive')

elif x < 0:

print(x, 'is negative')

else:

print(x, 'is zero')

What is the problem with the following code?

grade = 85

if grade >= 70:

print('grade is C')

elif grade >= 80:

print('grade is B')

elif grade >= 90:

print('grade is A')

A list stores many values in a single structure.

T = [27.3, 27.5, 27.7, 27.5, 27.6] # array of temperature measurements

print('temperature:', T)

print('length:', len(T))

print('zeroth item of T is', T[0])

print('fourth item of T is', T[4])

T[0] = 21.3

print('temperature is now:', T)

primes = [2, 3, 5]

print('primes is initially', primes)

primes.append(7) # append at the end

primes.append(11)

print('primes has become', primes)

print('primes before', primes)

del primes[4] # remove element #4

print('primes after', primes)

a = [] # start with an empty list

a.append('Vancouver')

a.append('Toronto')

a.append('Kelowna')

print(a)

a[99] # will give an error message (past the end of the array)

a[-1] # display the last element; what's the other way?

a[:] # will display all elements

a[1:] # starting from #1

a[:1] # ending with but not including #1

Lists can be heterogeneous and nested:

a = [11, 21, 31]

b = ['Mercury', 'Venus', 'Earth']

c = 'hello'

nestedList = [a, b, c]

print(nestedList)

You can search inside a list:

'Venus' in b # returns True

'Mars' in b # returns False

b.index('Venus') # returns 1 (position index)

And you sort lists alphabetically:

b.sort()

b # returns ['Earth', 'Mercury', 'Venus']

To delete an item from a list:

b.pop(2) # you can use its index

b.remove('Earth') # or you can use its value

Exercise: write a script to find the second largest number in the list [77,9,23,67,73,21].

For loops are very common in Python and are similar to for in other languages, but one nice twist with Python is that you can iterate over any collection, e.g., a list, a character string, etc.

for number in [2, 3, 5]: # number is the loop variable; [...] is a collection

print(number) # Python uses indentation to show the body of the loop

This is equivalent to:

print(2)

print(3)

print(5)

What will this do:

for number in [2, 3, 5]:

print(number)

print(number)

- the loop variable could be called anything

- the body of a loop can contain many statements

- use range to iterate over a sequence of numbers

for i in 'hello':

print(i)

for i in range(0,3):

print(i)

Let's sum numbers 1 to 10:

total = 0

for number in range(10):

total = total + (number + 1) # what's the other way to sum numbers 1 to 10? how about range(1,11)?

print(total)

Quiz 3: revert a string

Exercise: Print a difference between two lists, e.g., [1, 2, 3, 4] and [1, 2, 5].

Exercise: write a script to get the frequency of the elements in a list. You are allowed to google this problem :)

Since we talk about loops, we should also briefly mention while loops, e.g.

x = 2

while x > 1.:

x /= 1.1

print(x)

You can also form a zip object of tuples from two lists of the same length:

for i, j in zip(a,b):

print(i,j)

And you can create an enumerate object from a list:

for i, j in enumerate(b): # creates a list of tuples with an iterator as the first element

print(i,j)

It's a compact way to create new lists based on existing lists/collections. Let's list squares of numbers from 1 to 10:

[x**2 for x in range(1,11)]

Of these, list only odd squares:

[x**2 for x in range(1,11) if x%2==1]

You can also use list comprehensions to combine information from two or more lists:

week = ['Mon', 'Tue', 'Wed', 'Thu', 'Fri', 'Sat', 'Sun']

weekend = ['Sat', 'Sun']

print([day for day in week]) # the entire week

print([day for day in week if day not in weekend]) # only the weekdays

print([day for day in week if day in weekend]) # in both lists

The syntax is:

[something(i) for i in list1 if i [not] in list2 if i [not] in list3 ...]

Quiz 4: sum up squares of numbers

Exercise: Write a script to build a list of words that are shorter than n from a given list of words ['red', 'green', 'white', 'black', 'pink', 'yellow'].

Lists in Python are ordered sets of objects that you access via their position/index. Dictionaries are unordered sets in which the objects are accessed via their keys. In other words, dictionaries are unordered key-value pairs.

favs = {'mary': 'orange', 'john': 'green', 'eric': 'blue'}

favs

favs['john'] # returns 'green'

favs['mary'] # returns 'orange'

list(favs.values()).index('blue') # will return the index of the first value 'blue'

for key in favs:

print(key) # will print the names

for k in favs.keys():

print(k) # the same

for key in favs:

print(favs[key]) # will print the colours

for v in favs.values():

print(v) # the same

for i, j in favs.items():

print(i,j) # both the names and the colours

Now let's see how to add items to a dictionary:

concepts = {}

concepts['list'] = 'an ordered collection of values'

concepts['dictionary'] = 'a collection of key-value pairs'

concepts

Let's modify values:

concepts['list'] = 'simple: ' + concepts['list']

concepts['dictionary'] = 'complex: ' + concepts['dictionary']

concepts

Deleting dictionary items:

del concepts['list'] # remove the key 'list' and its value

Values can also be numerical:

grades = {}

grades['mary'] = 5

grades['john'] = 4.5

grades

And so can be the keys:

grades[1] = 2

grades

Sorting dictionary items:

favs = {'mary': 'orange', 'john': 'green', 'eric': 'blue', 'jane': 'orange'}

sorted(favs) # returns the sorted list of keys

sorted(favs.keys()) # the same

sorted(favs.values()) # returns the sorted list of values

for k in sorted(favs):

print(k, favs[k]) # full dictionary sorted by the key

Exercise: Write a script to print the full dictionary sorted by the value.

Similar to list comprehensions, we can form a dictionary comprehension:

{k:'.'*k for k in range(10)}

{k:v*2 for (k,v) in zip(range(10),range(10))}

{j:c for j,c in enumerate('computer')}

- functions encapsulate complexity so that we can treat it as a single thing

- functions enable re-use: write one time, use many times

First define:

def greeting():

print('Hello!')

and then we can run it:

greeting()

def printDate(year, month, day):

joined = str(year) + '/' + str(month) + '/' + str(day)

print(joined)

printDate(1871, 3, 19)

Every function returns something, even if it's None.

a = printDate(1871, 3, 19)

print(a)

How do we actually return a value from a function?

def average(values): # the argument is a list

if len(values) == 0:

return None

return sum(values) / len(values)

a = average([1, 3, 4])

print('average of actual values:', a)

Quiz 5: convert from Fahrenheit to Celsius

Quiz 6: convert from Celsius to Fahrenheit

Quiz 7: convert temperature lists

Function arguments in Python can take default values becoming optional:

def addNumber(a, b=1):

return a+b

print(addNumber(5))

print(addNumber(5,3))

With several optional arguments it is important to be able to differentiate them:

def modify(a, b=1, coef=1):

return a*coef + b

print(modify(10))

print(modify(10, 1)) # which argument did we add?

print(modify(10, coef=2))

print(modify(10, coef=2, b=5))

Any complex python function will have many optional arguments, for example:

?print

The scope of a variable is the part of a program that can see that variable.

a = 5

def adjust(b):

sum = a + b

return sum

adjust(10) # what will be the outcome?

- "a" is the global variable => visible everywhere

- "b" and "sum" are local variables => visible only inside the function

Inside a function we can access methods of global variables:

a = []

def add():

a.append(5) # modify global `a`

add()

a # [5]

(1) How would you explain the following:

1 + 2 == 3 # returns True (makes sense!)

0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3 # returns False -- be aware of this when you use conditionals

abs(0.1+0.2 - 0.3) < 1.e-8 # compare floats for almost equality

import numpy as np

np.isclose(0.1+0.2, 0.3, atol=1e-8)

(2) More challening: write a code to solve x^3+4x^2-10=0 with a bisection method in the interval [1.3, 1.4] with tolerance 1e-8.

Most of the power of a programming language is in its libraries. This is especially true for Python which is an interpreted language and is therefore very slow (compared to compiled languages). However, the libraries are often compiled (can be written in compiled languages such as C/C++) and therefore offer much faster performance than native Python code.

A library is a collection of functions that can be used by other programs. Python's standard library includes many functions we worked with before (print, int, round, ...) and is included with Python. There are many other additional modules in the standard library such as math:

print('pi is', pi)

import math

print('pi is', math.pi)

You can also import math's items directly:

from math import pi, sin

print('pi is', pi)

sin(pi/6)

cos(pi)

help(math) # help for libraries works just like help for functions

from math import *

You can also create an alias from the library:

import math as m

print m.pi

Quiz 8: exploring the math library

Quiz 9: random numbers

Quiz 10: forgot to load the library

Quiz 11: degree conversion with math

To install a package into the current Python environment from inside a Jupyter notebook, simply do:

%pip install packageName

In Python you can create an isolated environment for each project, into which all of its dependencies will be installed. This could be useful if your several projects have very different sets of dependencies. On the computer running your Jupyter notebooks, open the terminal and type:

pip install virtualenv

virtualenv climate # create a new virtual environment in your current directory

source climate/bin/activate

which python && which pip

pip install numpy ...

pip install ipykernel # install ipykernel (IPython kernel for Jupyter) into this environment

python -m ipykernel install --user --name=climate # add your environment to Jupyter

...

deactivate

Quit all your currently running Jupyter notebooks and the Jupyter dashboard. If running on syzygy.ca, logout from your session and then log back in.

Whether running locally or on syzygy.ca, open the notebook dashboard, and one of the options in New below Python 3

should be climate.

To delete the environment, in the terminal type:

jupyter kernelspec list # `climate` should be one of them

jupyter kernelspec uninstall climate # remove your environment from Jupyter

/bin/rm -rf climate

As you saw before, Python is not statically typed, i.e. variables can change their type on the fly:

a = 5

a = 'apple'

print(a)

This makes Python very flexible. Out of these variables you form 1D lists, and these can be inhomogeneous:

a = [1, 2, 'Vancouver', ['Earth', 'Moon'], {'list': 'an ordered collection of values'}]

a[1] = 'Sun'

a

Python lists are very general and flexible, which is great for high-level programming, but it comes at a cost. The Python interpreter can't make any assumptions about what will come next in a list, so it treats everything as a generic object with its own type and size. As lists get longer, eventually performance takes a hit.

Python does not have any mechanism for a uniform/homogeneous list, where -- to jump to element #1000 -- you just take

the memory address of the very first element and then increment it by (element size in bytes) x 999. Numpy library

fills this gap by adding the concept of homogenous collections to python -- numpy.ndarrays -- which are

multidimensional, homogeneous arrays of fixed-size items (most commonly numbers).

- This brings large performance benefits!

- no reading of extra bits (type, size, reference count)

- no type checking

- contiguous allocation in memory

- numpy lets you work with mathematical arrays.

Lists and numpy arrays behave very differently:

a = [1, 2, 3, 4]

b = [5, 6, 7, 8]

a + b # this will concatenate two lists: [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

import numpy as np

na = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

nb = np.array([5, 6, 7, 8])

na + nb # this will sum two vectors element-wise: array([6,8,10,12])

na * nb # element-wise product

Numpy arrays have the following attributes:

- ndim = the number of dimensions

- shape = a tuple giving the sizes of the dimensions

- size = the total number of elements

- dtype = the data type

- itemsize = the size (bytes) of individual elements

- nbytes = the total memory (bytes) occupied by the ndarray

- strides = tuple of bytes to step in each dimension when traversing an array

- data = memory address of the array

a = np.arange(10) # 10 integer elements 0..9

a.ndim # 1

a.shape # (10,)

a.nbytes # 80

a.dtype # dtype('int64')

b = np.arange(10, dtype=np.float)

b.dtype # dtype('float64')

In numpy there are many ways to create arrays:

np.arange(11,20) # 9 integer elements 11..19

np.linspace(0, 1, 100) # 100 numbers uniformly spaced between 0 and 1 (inclusive)

np.linspace(0, 1, 100).shape

np.zeros(100, dtype=np.int) # 1D array of 100 integer zeros

np.zeros((5, 5), dtype=np.float64) # 2D 5x5 array of floating zeros

np.ones((3,3,4), dtype=np.float64) # 3D 3x3x4 array of floating ones

np.eye(5) # 2D 5x5 identity/unit matrix (with ones along the main diagonal)

You can create random arrays:

np.random.randint(0, 10, size=(4,5)) # 4x5 array of random integers in the half-open interval [0,10)

np.random.random(size=(4,3)) # 4x3 array of random floats in the half-open interval [0.,1.)

np.random.rand(3, 3) # 3x3 array drawn from a uniform [0,1) distribution

np.random.randn(3, 3) # 3x3 array drawn from a normal (Gaussian with x0=0, sigma=1) distribution

For 1D arrays:

a = np.linspace(0,1,100)

a[0] # first element

a[-2] # 2nd to last element

a[5:12] # values [5..12), also a numpy array

a[5:12:3] # every 3rd element in [5..12), i.e. elements 5,8,11

a[::-1] # array reversed

Similar for multi-dimensional arrays:

b = np.reshape(np.arange(100),(10,10)) # form a 10x10 array from 1D array

b[0:2,1] # first two rows, second column

b[:,-1] # last column

b[5:7,5:7] # 2x2 block

a = np.array([1, 2, 3, 4])

b = np.array([4, 3, 2, 1])

np.vstack((a,b)) # stack them vertically into a 2x4 array (use a,b as rows)

np.hstack((a,b)) # stack them horizontally into a 1x8 array

np.column_stack((a,b)) # use a,b as columns

One of the big reasons for using numpy is so you can do fast numerical operations on a large number of elements. The

result is another ndarray. In many calculations you can use replace the usual for/while loops with functions on

numpy elements.

a = np.arange(100)

a**2 # each element is a square of the corresponding element of a

np.log10(a+1) # apply this operation to each element

(a**2+a)/(a+1) # the result should effectively be a floating-version copy of a

np.arange(10) / np.arange(1,11) # this is np.array([ 0/1, 1/2, 2/3, 3/4, ..., 9/10 ])

Exercise: Let's verify the equation

using summation of elements of an

ndarray.Hint: Start with the first 10 terms

k = np.arange(1,11). Then try the first 30 terms.

An extremely useful feature of ufuncs is the ability to operate between arrays of different sizes and shapes, a set of operations known as broadcasting.

a = np.array([0, 1, 2]) # 1D array

b = np.ones((3,3)) # 2D array

a + b # `a` is stretched/broadcast across the 2nd dimension before addition;

# effectively we add `a` to each row of `b`

In the following example both arrays are broadcast from 1D to 2D to match the shape of the other:

a = np.arange(3) # 1D row; a.shape is (3,)

b = np.arange(3).reshape((3,1)) # effectively 1D column; b.shape is (3, 1)

a + b # the result is a 2D array!

Numpy's broadcast rules are:

- the shape of an array with fewer dimensions is padded with 1's on the left

- any array with shape equal to 1 in that dimension is stretched to match the other array's shape

- if in any dimension the sizes disagree and neither is equal to 1, an error is raised

Example 1:

==========

a: (2,3) -> (2,3) -> (2,3)

b: (3,) -> (1,3) -> (2,3)

-> (2,3)

Example 2:

==========

a: (3,1) -> (3,1) -> (3,3)

b: (3,) -> (1,3) -> (3,3)

-> (3,3)

Example 3:

==========

a: (3,2) -> (3,2) -> (3,2)

b: (3,) -> (1,3) -> (3,3)

-> error

"ValueError: operands could not be broadcast together with shapes (3,2) (3,)"

Note on numpy speed: As chance would have it, last week I was working with a spherical dataset describing Earth's mantle convection. It is on a spherical grid with 13e6 grid points. For each grid point, I was converting from the spherical (lateral - radial - longitudinal) velocity components to the Cartesian velocity components. For each point this is a matrix-vector multiplication. Doing this by hand with Python's

forloops would take many hours for 13e6 points. I used numpy to vectorize in one dimension, and that cut the time to ~5 mins. At first glance, a more complex vectorization would not work, as numpy would have to figure out which dimension goes where. Writing it carefully and following the broadcast rules I made it work, with the correct solution at the end -- while the total compute time went down to a few seconds!

Let's use broadcasting to plot a 2D function with matplotlib:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

x = np.linspace(0, 5, 50)

y = np.linspace(0, 5, 50).reshape(50,1)

z = np.sin(x)**8 + np.cos(5+x*y)*np.cos(x) # broadcast in action!

plt.imshow(z)

plt.colorbar(shrink=0.8)

Exercise: Use numpy broadcasting to build a 3D array from three 1D ones.

Aggregate functions take an ndarray and reduce it along one (or more) axes. E.g., in 1D:

a = np.linspace(1, 2, 100)

a.mean() # arithmetic mean

a.max() # maximum value

a.argmax() # index of the maximum value

a.sum() # sum of all values

a.prod() # product of all values

Or in 2D:

b = np.arange(25).reshape(5,5)

>>> b.sum()

300

b.sum(axis=0) # add rows

b.sum(axis=1) # add columns

a = np.linspace(1, 2, 100)

a < 1.5

a[a < 1.5] # will only return those elements that meet the condition

a[a < 1.5].shape

a.shape

Numpy provides many standard linear algebra algorithms: matrix/vector products, decompositions, eigenvalues, solving linear equations, e.g.

a = np.array([[3,1], [1,2]])

b = np.array([9,8])

x = np.linalg.solve(a, b)

x

np.allclose(np.dot(a, x),b) # check the solution

A lot of other packages are built on top of numpy. E.g., there is a Python package for analysis and visualization of 3D multi-resolution volumetric data called yt which is based on numpy. Check out this visualization produced with yt.

Many image-processing libraries use numpy data structures underneath, e.g.

import skimage.io # scikit-image is a collection of algorithms for image processing

image = skimage.io.imread(fname="https://raw.githubusercontent.com/razoumov/publish/master/grids.png")

image.shape # it's a 1024^2 image, with (R,G,B,\alpha) channels

Let's plot this image using matplotlib:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

plt.imshow(image[:,:,2], interpolation='nearest')

plt.colorbar(orientation='vertical', shrink=0.75, aspect=50)

Using numpy, you can easily manipulate pixels:

image[:,:,2] = 255 - image[:,:,2]

and then rerun the previous (matplotlib) cell.

Another example of a package built on top of numpy is pandas, for working with 2D tables. Going further, xarray was built on top of both numpy and pandas.

One of the most widely used Python plotting libraries is matplotlib. Matplotlib is open source and produces static images.

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

from numpy import linspace, sin

x = linspace(0.01,1,300)

y = sin(1/x)

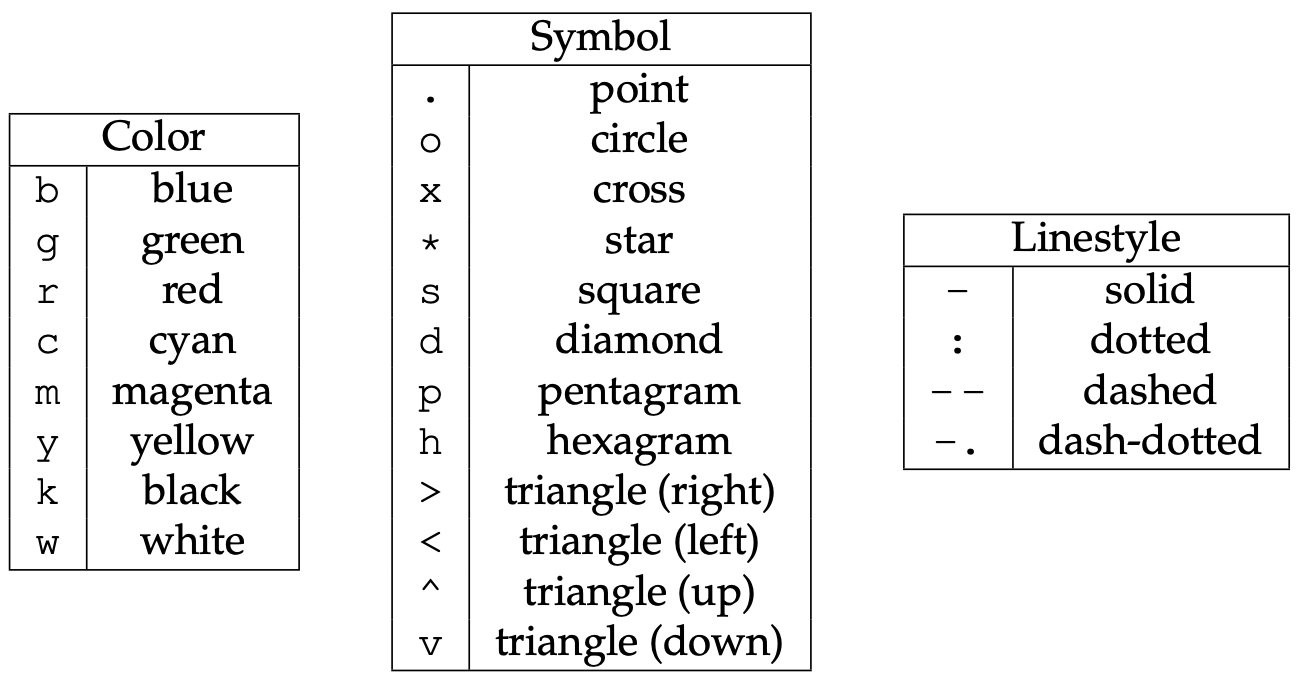

plt.plot(x, y, 'bo-')

plt.xlabel('x', fontsize=18)

plt.ylabel('f(x)', fontsize=18)

# plt.show() # not needed inside the Jupyter notebook

# plt.savefig('tmp.png')

Let's add the second line, the labels, and the legend. Note that matplotlib automatically adjusts the axis ranges to fit both plots:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

from numpy import linspace, sin

x = linspace(0.01,1,300)

y = sin(1/x)

plt.plot(x, y, 'bo-', label='one')

plt.plot(x+0.3, 2*sin(10*x), 'r-', label='two')

plt.legend(loc='lower right')

plt.xlabel('x', fontsize=18)

plt.ylabel('f(x)', fontsize=18)

Let's plot these two functions side-by-side:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,4))

from numpy import linspace, sin

x = linspace(0.01,1,300)

y = sin(1/x)

ax = fig.add_subplot(121) # on 1x2 layout create plot #1 (`axes` object with some data space)

a1 = plt.plot(x, y, 'bo-', label='one')

ax.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('f1')

ax = fig.add_subplot(122) # on 1x2 layout create plot #2

a2 = plt.plot(x+0.2, 2*sin(10*x), 'r-', label='two')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('f2')

Instead of indices, we could specify the absolute coordinates of each plot with fig.add_axes():

- adjust the size

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,4)) - replace the first

fig.add_subplotwithax = fig.add_axes([0.1, 0.7, 0.8, 0.3]) # left, bottom, width, height - replace the second

fig.add_subplotwithax = fig.add_axes([0.1, 0.2, 0.8, 0.4]) # left, bottom, width, height

The 3rd option is plt.axes() -- it creates an axes object (a region of the figure with some data space). These two

lines are equivalent - both create a new figure with one subplot:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,8)); ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8,8)); ax = plt.axes()

Exercise: break the plot into two subplots, the fist taking 1/3 of the space on the left, the second one 2/3 of the space on the right.

Let's plot a simple line in the x-y plane:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

x = np.linspace(0,1,100)

plt.plot(2*np.pi*x, x, 'b-')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('f1')

Replace ax = fig.add_subplot(111) with ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='polar'). Now we have a plot in the

phi-r plane, i.e. in polar coordinates. Phi goes [0,2\pi], whereas r goes [0,1].

?fig.add_subplot # look into `projection` parameter

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='mollweide')

x = np.radians([30,40, 50])

y = np.radians([15, 16, 17])

plt.plot(x, y, 'bo-')

Later, we'll learn how to use this projection parameter with cartopy to map your 2D data from one projection to

another.

Let's try a scatter plot:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

plt.figure(figsize=(10,8))

x = np.random.random(size=1000) # 1D array of 1000 random numbers in [0.,1.]

y = np.random.random(size=1000)

size = 1 + 50*np.random.random(size=1000)

plt.scatter(x, y, s=size, color='lightblue')

For other plot types click on any example in the Matplotlib gallery.

For colours, see Choosing Colormaps in Matplotlib.

Let's plot a heatmap of monthly temperatures at the South Pole:

%matplotlib inline

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import cm

import numpy as np

plt.figure(figsize=(15,10))

months = ['Jan', 'Feb', 'Mar', 'Apr', 'May', 'Jun', 'Jul', 'Aug', 'Sep', 'Oct', 'Nov', 'Dec', 'Year']

recordHigh = [-14.4,-20.6,-26.7,-27.8,-25.1,-28.8,-33.9,-32.8,-29.3,-25.1,-18.9,-12.3,-12.3]

averageHigh = [-26.0,-37.9,-49.6,-53.0,-53.6,-54.5,-55.2,-54.9,-54.4,-48.4,-36.2,-26.3,-45.8]

dailyMean = [-28.4,-40.9,-53.7,-57.8,-58.0,-58.9,-59.8,-59.7,-59.1,-51.6,-38.2,-28.0,-49.5]

averageLow = [-29.6,-43.1,-56.8,-60.9,-61.5,-62.8,-63.4,-63.2,-61.7,-54.3,-40.1,-29.1,-52.2]

recordLow = [-41.1,-58.9,-71.1,-75.0,-78.3,-82.8,-80.6,-79.3,-79.4,-72.0,-55.0,-41.1,-82.8]

vlabels = ['record high', 'average high', 'daily mean', 'average low', 'record low']

Z = np.stack((recordHigh,averageHigh,dailyMean,averageLow,recordLow))

plt.imshow(Z, cmap=cm.winter)

plt.colorbar(orientation='vertical', shrink=0.45, aspect=20)

plt.xticks(range(13), months, fontsize=15)

plt.yticks(range(5), vlabels, fontsize=12)

plt.ylim(-0.5, 4.5)

for i in range(len(months)):

for j in range(len(vlabels)):

text = plt.text(i, j, Z[j,i],

ha="center", va="center", color="w", fontsize=14, weight='bold')

Exercise: Change the text colour to black in the brightest (green) rows and columns. You can do this either by specifying rows/columns explicitly, or (better) by setting a threshold background colour.

Exercise: Modify the code to display only 4 seasons instead of the individual months.

For this we need a data file -- let's download it. Open a terminal inside your Jupyter dashboard. Inside the terminal, type:

wget http://bit.ly/pythfiles -O pfiles.zip

unzip pfiles.zip && rm pfiles.zip # this should unpack into the directory data-python/

You can now close the terminal panel. Let's switch back to our Python notebook and check our location:

%pwd # simply run a bash command with a prefix

%ls # make sure you see data-python/

Let's plot tabulated topographic elevation data:

~~~ {.python}

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm

from matplotlib.colors import LightSource

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

table = pd.read_csv('data-python/mt_bruno_elevation.csv')

z = np.array(table)

nrows, ncols = z.shape

x = np.linspace(0,1,ncols)

y = np.linspace(0,1,nrows)

x, y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

ls = LightSource(270, 45)

rgb = ls.shade(z, cmap=cm.gist_earth, vert_exag=0.1, blend_mode='soft')

fig, ax = plt.subplots(subplot_kw=dict(projection='3d'), figsize=(10,10)) # figure with one subplot

ax.view_init(20, 30) # (theta, phi) viewpoint

surf = ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, facecolors=rgb, linewidth=0, antialiased=False, shade=False)

Exercise: replace

fig, ax = plt.subplots()withfig = plt.figure()followed byax = fig.add_subplot(). Don't forget about the3dprojection.

Let's replace the last two lines with (running this takes ~10s on my laptop):

ax.view_init(20, 30)

surf = ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, facecolors=rgb, linewidth=0, antialiased=False, shade=False)

for angle in range(90):

print(angle)

ax.view_init(20, 30+angle)

plt.savefig('frame%04d'%(angle)+'.png')

And then we can create a movie in bash:

ffmpeg -r 30 -i frame%04d.png -c:v libx264 -pix_fmt yuv420p -vf "scale=trunc(iw/2)*2:trunc(ih/2)*2" spin.mp4

Here is something visually very different, still using ax.plot_surface():

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm

from matplotlib.colors import LightSource

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from numpy import pi, sin, cos, mgrid

dphi, dtheta = pi/250, pi/250 # 0.72 degrees

[phi, theta] = mgrid[0:pi+dphi*1.5:dphi, 0:2*pi+dtheta*1.5:dtheta]

# define two 2D grids: both phi and theta are (252,502) numpy arrays

r = sin(4*phi)**3 + cos(2*phi)**3 + sin(6*theta)**2 + cos(6*theta)**4

x = r*sin(phi)*cos(theta) # x is also (252,502)

y = r*cos(phi) # y is also (252,502)

z = r*sin(phi)*sin(theta) # z is also (252,502)

ls = LightSource(270, 45)

rgb = ls.shade(z, cmap=cm.gist_earth, vert_exag=0.1, blend_mode='soft')

fig, ax = plt.subplots(subplot_kw=dict(projection='3d'), figsize=(10,10))

ax.view_init(20, 30)

surf = ax.plot_surface(x, y, z, facecolors=rgb, linewidth=0, antialiased=False, shade=False)

Xarray library is built on top of numpy and pandas, and it brings the power of pandas to multidimensional arrays. There are two main data structures in xarray:

- xarray.DataArray is a fancy, labelled version of numpy.ndarray

- xarray.Dataset is a collection of multiple xarray.DataArray's that share dimensions

import xarray as xr

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

data = xr.DataArray(

np.random.random(size=(4,3)),

dims=("y","x"), # dimension names (row,col); we want `y` to represent rows and `x` columns

coords={"x": [10,11,12], "y": [10,20,30,40]} # coordinate labels/values

)

dataWe can access various attributes of this array:

data.values # the 2D numpy array

data.values[0,0] = 0.53 # can modify in-place

data.dims # ('y', 'x')

data.coords # all coordinates, cannot modify!

data.coords['x'][1] # a number

data.x[1] # the sameLet's add some arbitrary metadata:

data.attrs = {"author": "AR", "date": "2020-08-26"}

data.attrs["name"] = "density"

data.attrs["units"] = "g/cm^3"

data.x.attrs["units"] = "cm"

data.y.attrs["units"] = "cm"

data.attrs # all attributes

data # all attributes show here as well

data.x # only `x` attributesWe can subset using the usual Python square brackets:

data[0,:] # first row

data[:,-1] # last columnIn addition, xarray provides these functions:

- isel() selects by index, could be replaced by [index1] or [index1,...]

- sel() selects by value

- interp() interpolates by value

data.isel() # same as `data`

data.isel(y=1) # second row

data.isel(y=0, x=[-2,-1]) # first row, last two columnsdata.x.dtype # it is integer

data.sel(x=10) # certain value of `x`

data.y # array([10, 20, 30, 40])

data.sel(y=slice(15,30)) # only values with 15<=y<=30 (two rows)There are aggregate functions, e.g.

meanOfEachColumn = data.mean(dim='y') # apply mean over y

spatialMean = data.mean()

spatialMean = data.mean(dim=['x','y']) # sameFinally, we can interpolate:

data.interp(x=10.5, y=10) # first row, between 1st and 2nd columns

data.interp(x=10.5, y=15) # between 1st and 2nd rows, between 1st and 2nd columns

?data.interp # can use different interpolation methodsMatplotlib is integrated directly into xarray:

data.plot(size=8) # 2D heatmap

data.isel(x=0).plot(marker="o", size=8) # 1D line plotYou can perform element-wise operations on xarray.DataArray like with numpy.ndarray:

data + 100 # element-wise like numpy arrays

(data - data.mean()) / data.std() # normalize the data

data - data[0,:] # use numpy broadcasting => subtract first row from all rowsdata.groupby("x") # 3 groups with labels 10, 11, 12

data.groupby("x").map(lambda v: v-v.min()) # apply separately to each group

# from each column (fixed x) subtract the smallest value in that columnLet's initialize two 2D arrays with the identical dimensions:

coords = {"x": np.linspace(0,1,5), "y": np.linspace(0,1,5)}

temp = xr.DataArray( # first 2D array

20 + np.random.randn(5,5),

dims=("y","x"),

coords=coords

)

pres = xr.DataArray( # second 2D array

100 + 10*np.random.randn(5,5),

dims=("y","x"),

coords=coords

)From these we can form a dataset:

ds = xr.Dataset({"temperature": temp, "pressure": pres,

"bar": ("x", 200+np.arange(5)), "pi": np.pi})

dsAs you can see, ds includes two 2D arrays on the same grid, one 1D array on x, and one number:

ds.temperature # 2D array

ds.bar # 1D array

ds.pi # one elementSubsetting works the usual way:

ds.sel(x=0) # each 2D array becomes 1D array, the 1D array becomes a number, plus a number

ds.temperature.sel(x=0) # 'temperature' is now a 1D array

ds.temperature.sel(x=0.25, y=0.5) # one element of `temperature`We can save this dataset to a file:

%pip install netcdf4

ds.to_netcdf("test.nc")

new = xr.open_dataset("test.nc") # try reading itWe can even try opening this 2D dataset in ParaView - select (x,y) and deselect Spherical.

Exercise: Recall the 2D function we plotted when we were talking about numpy's array broadcasting. Let's scale it to a unit square x,y∈[0,1]:

x = np.linspace(0, 1, 50) y = np.linspace(0, 1, 50).reshape(50,1) z = np.sin(5*x)**8 + np.cos(5+25*x*y)*np.cos(5*x)This is will our image at z=0. Then rotate this image 90 degrees (e.g. flip x and y), and this will be our function at z=1. Now interpolate linearly between z=0 and z=1 to build a 3D function in the unit cube x,y,z∈[0,1]. Check what the function looks like at intermediate z. Write out a NetCDF file with the 3D function.

In xarray you can work with time-dependent data. Xarray accepts pandas time formatting,

e.g. pd.to_datetime("2020-09-10") would produce a timestamp. To produce a time range, we can use:

import pandas as pd

time = pd.date_range("2000-01-01", freq="D", periods=365*3+1) # 2000-Jan to 2002-Dec (3 full years)

time

time.month # same length (1096), but each element is replaced by the month number

time.day # same length (1096), but each element is replaced by the day-of-the-month

?pd.date_range

Using this time construct, let's initialize a time-dependent dataset that contains a scalar temperature variable (no

space) mimicking seasonal change. We can do this directly without initializing an xarray.DataArray first -- we just need

to specify what this temperature variable depends on:

import xarray as xr

import numpy as np

ntime = len(time)

temp = 10 + 5*np.sin((250+np.arange(ntime))/365.25*2*np.pi) + 2*np.random.randn(ntime)

ds = xr.Dataset({ "temperature": ("time", temp), # it's 1D function of time

"time": time })

ds.temperature.plot(size=8)

We can do the usual subsetting:

ds.isel(time=100) # 101st timestep

ds.sel(time="2002-12-22")

Time dependency in xarray allows resampling with a different timestep:

ds.resample(time='7D') # 1096 times -> 157 time groups

weekly = ds.resample(time='7D').mean() # compute mean for each group

weekly.temperature.plot(size=8)

Now, let's combine spatial and time dependency and construct a dataset containing two 2D variables (temperature and pressure) varying in time. The time dependency is baked into the coordinates of these xarray.DataArray's and should come before the spatial coordinates:

time = pd.date_range("2020-01-01", freq="D", periods=91) # January - March 2020

ntime = len(time)

n = 100 # spatial resolution in each dimension

axis = np.linspace(0,1,n)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(axis,axis) # 2D Cartesian meshes of x,y coordinates

initialState = (1-Y)*np.sin(np.pi*X) + Y*(np.sin(2*np.pi*X))**2

finalState = (1-X)*np.sin(np.pi*Y) + X*(np.sin(2*np.pi*Y))**2

f = np.zeros((ntime,n,n))

for t in range(ntime):

z = (t+0.5) / ntime # dimensionless time from 0 to 1

f[t,:,:] = (1-z)*initialState + z*finalState

coords = {"time": time, "x": axis, "y": axis}

temp = xr.DataArray(

20 + f, # this 2D array varies in time from initialState to finalState

dims=("time","y","x"),

coords=coords

)

pres = xr.DataArray( # random 2D array

100 + 10*np.random.randn(ntime,n,n),

dims=("time","y","x"),

coords=coords

)

ds = xr.Dataset({"temperature": temp, "pressure": pres})

ds.sel(time="2020-03-15").temperature.plot(size=8) # temperature distribution on a specific date

ds.to_netcdf("evolution.nc")

The file evolution.nc should be 100^2 x 2 variables x 8 bytes x 91 steps = 14MB. We can load it into ParaView and play

back the pressure and temperature!

So far we've been working with datasets in Cartesian coordinates. How about spherical geometry -- how do we initialize and store a dataset in spherical coordinates (longitude - latitude - elevation)? Very easy: define these coordinates and your data arrays on top, put everything into an xarray dataset, and then specify the following units:

ds.lat.attrs["units"] = "degrees_north" # this line is important to adhere to CF convention

ds.lon.attrs["units"] = "degrees_east" # this line is important to adhere to CF convention

Exercise: Let's do it! Create a small (one-degree horizontal + some vertical resolution), stationary (no

time dependency) dataset in spherical geometry with one 3D variable and write it to spherical.nc. Load it into

ParaView to make sure the geometry is spherical.

I took one of the ECCC historical model datasets (contains only the near-surface air temperature) published on the CMIP6 Data-Archive and reduced its size picking only a subset of timesteps:

import xarray as xr

data = xr.open_dataset('/Users/razoumov/tmp/xarray/atmosphere/tas_Amon_CanESM5_historical_r1i1p2f1_gn_185001-201412.nc')

data.sel(time=slice('2001', '2020')).to_netcdf("tasReduced.nc") # last 168 steps

Let's download this file in the terminal:

wget http://bit.ly/atmosdata -O tasReduced.nc

First, quickly check this dataset in ParaView (use Dimensions = (lat,lon)).

data = xr.open_dataset('tasReduced.nc')

data # this is a time-dependent 2D dataset: print out the metadata, coordinates, data variables

data.time # time goes monthly from 2001-01-16 to 2014-12-16

data.tas # metadata for the data variable (time: 168, lat: 64, lon: 128)

data.tas.shape # (168, 64, 128) = (time, lat, lon)

data.height # at the fixed height=2m

These five lines all produce the same result:

data.tas[0] - 273.15 # take all values in the second and third dims, convert to Celsius

data.tas[0,:] - 273.15

data.tas[0,:,:] - 273.15

data.tas.isel(time=0) - 273.15

air = data.tas.sel(time='2001-01-16') - 273.15

These two lines produce the same result (1D vector of temperatures as a function of longitude):

data.tas[0,5]

data.tas.isel(time=0, lat=5)

Check temperature variation in the last step:

air = data.tas.isel(time=-1) - 273.15 # last timestep, to celsius

air.shape # (64, 128)

air.min(), air.max() # -43.550903, 36.82956

Selecting data is slightly more difficult with approximate floating coordinates:

data.tas.lat

data.tas.lat.dtype

data.tas.isel(lat=0) # the first value lat=-87.86

data.lat[0] # print the first latitude and try to use it below

data.tas.sel(lat=-87.86379884) # does not work due to floating precision

data.tas.sel(lat=data.lat[0]) # this works

latSlice = data.tas.sel(lat=slice(-90,-80)) # only select data in a slice lat=[-90,-80]

latSlice.shape # (168, 3, 128) - 3 latitudes in this slice

Multiple ways to select time:

data.time[-10:] # last ten times

air = data.tas.sel(time='2014-12-16') - 273.15 # last date

air = data.tas.sel(time='2014') - 273.15 # select everything in 2014

air.shape # 12 steps

air.time

air = data.tas.sel(time='2014-01') - 273.15 # select everything in January 2014

Aggregate functions:

meanOverTime = data.tas.mean(dim='time') - 273.15

meanOverSpace = data.tas.mean(dim=['lat','lon']) - 273.15 # mean over space for each timestep

meanOverSpace.shape # time series (168,)

meanOverSpace.plot(marker="o", size=8) # calls matplotlib.pyplot.plot

Interpolate to a specific location:

victoria = data.tas.interp(lat=48.43, lon=360-123.37)

victoria.shape # (168,) only time

victoria.plot(marker="o", size=8) # simple 1D plot

victoria.sel(time=slice('2001','2020')).plot(marker="o", size=8) # zoom in on the 21st-century points, see seasonal variations

Let's plot in 2D:

air = data.tas.isel(time=-1) - 273.15 # last timestep

air.time

air.plot(size=8) # 2D plot, very poor resolution (lat: 64, lon: 128)

air.plot(size=8, y="lon", x="lat") # can specify which axis is which

What if we have time-dependency in the plot?

a = data.tas[-6:] - 273.15 # last 6 timesteps => 3D dataset => which coords to use for what?

a.plot(x="lon", y="lat", col="time", col_wrap=3)

Breaking into groups and applying a function to each group:

len(data.time) # 168 steps

data.tas.groupby("time") # 168 groups

def standardize(x):

return (x - x.mean()) / x.std()

standard = data.tas.groupby("time").map(standardize) # apply this function to each group

standard.shape # (1980, 64, 128) same shape as the original but now normalized over each group

Cartopy lets you process your geospatial data in order to produce maps, e.g. using various map projections. All plotting is still being done by Matplotlib.

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import cartopy.feature as cfeature

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.coastlines()

ax.coastlines(resolution='50m', color='gray', linewidth=2) # valid scales are "110m", "50m", "10m"

ax.add_feature(cfeature.OCEAN)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.LAND)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.BORDERS, linestyle=':')

Try the following projections (and bring online help on these):

- PlateCarree(0) is the equi-rectangular/Cartesian projection (meridians are vertical straight lines)

- Orthographic(-100,55)

- Mollweide(0)

- Robinson(0)

- InterruptedGoodeHomolosine(0)

More information on cartopy projections.

Let's only plot North America:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.Mollweide(-100))

ax.coastlines()

ax.add_feature(cfeature.OCEAN)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.LAND)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.BORDERS, linestyle=':')

ax.set_extent([-160, -51, 5, 85])

You can zoom in much further, and the high-resolution data will be downloaded from online sources. E.g. let's focus on Vancouver Island:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.coastlines()

ax.add_feature(cfeature.OCEAN)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.LAND)

ax.add_feature(cfeature.BORDERS, linestyle=':')

ax.set_extent([-129, -122, 46, 53])

Let's overlay the Natural Earth shaded relief on top of our map and display the night shade:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.Mollweide())

ax.stock_img() # add the Natural Earth shaded relief image

ax.add_feature(cfeature.BORDERS, linestyle=':')

import datetime

import pytz

date = datetime.datetime.now() # local time now

utc = datetime.datetime.utcnow() # UTC time now

date, utc

from cartopy.feature.nightshade import Nightshade

ax.add_feature(Nightshade(utc, alpha=0.2))

Let's plot 1D data (a line connecting two points on top of our map):

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12,12))

ax = plt.axes(projection=ccrs.Robinson(-150))

ax.stock_img()

vancouver = (-123.12, 49.28)

perth = (115.86, -31.95)

lon = [vancouver[0], perth[0]]

lat = [vancouver[1], perth[1]]

plt.plot(lon, lat, color='blue', linewidth=2, marker='o') # does not work!

We need to tell matplotlib that our line is a straight line in spherical geometry:

plt.plot(lon, lat, color='blue', linewidth=2, marker='o', transform=ccrs.Geodetic())

If you want to add a straight line in planar geometry:

plt.plot(lon, lat, color='gray', linestyle='--', transform=ccrs.PlateCarree())

Most matplotlib plotting functions will work with cartopy projections: lines (plot), heatmaps and images (plot or

imshow), scatter plots (scatter), vector plots (quiver). Let's plot our 2D atmospheric data with Cartopy

projections. Read the data again:

import xarray as xr

data = xr.open_dataset('tasReduced.nc')

temp = data.tas.sel(time="2014-12-16") - 273.15 # extract last timestep, convert to Celsius

temp.shape # (1, 64, 128)

temp.coords # the coordinates are 1D, so plotting is easy

The data is defined on a 2D Cartesian projection. First, let's plot data in the same projection:

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree())

ax.coastlines()

ax.gridlines()

temp.plot(ax=ax, cbar_kwargs={'shrink': 0.4}) # since we are using PlateCarree(), Cartopy assumes

# that the data is also in PlateCarree() coordinates, which is true

Now let's switch the projection. Then we have to tell Cartopy our data's coordinate system explicitly with transform:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.InterruptedGoodeHomolosine()) # use this projection

ax.coastlines()

ax.gridlines()

temp.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), cbar_kwargs={'shrink': 0.4})

# `transform` tells Cartopy the coordinate system of our data

Let's switch the projection and zoom in on Vancouver Island:

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.Mollweide(-125))

ax.coastlines()

ax.gridlines()

temp.plot(ax=ax, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), cbar_kwargs={'shrink': 0.4})

ax.set_extent([-129, -122, 46, 53])

We can see that our data is really low resolution.

I took another ECCC historical model dataset (containing 3D ocean temperature) published on the CMIP6 Data-Archive and reduced its size picking only a subset of timesteps:

import xarray as xr

data = xr.open_dataset('/Users/razoumov/tmp/xarray/ocean/thetao_Omon_CanESM5_historical_r1i1p2f1_gn_201101-201412.nc')

data.sel(time=slice('2014-10-16', '2014-12-16')).to_netcdf("thetaoReduced.nc") # last 3 steps

Let's download the file:

wget http://bit.ly/oceanfile -O thetaoReduced.nc

Estimating the file size 360x291x45 x 8 bytes x 3 steps / 1024^2 should result in 108MB, however, it is only 25MB due to NetCDF compression.

First, load it into ParaView:

- use Vertical Scale = -1 and Vertical Bias = 5e4

- pass through Threshold max = 100

- Rescale to All Timesteps

Now, let's load this data and plot it in Matplotlib:

import xarray as xr

data = xr.open_dataset('thetaoReduced.nc')

data

data.thetao.min(), data.thetao.max() # the data is in Celsius

data.thetao.shape

temp = data.thetao.isel(time=-1, lev=0) # extract last timestep, elevation level 0

latIndexNearEquator = int(temp.shape[0]/2)

temp[latIndexNearEquator].values # see how land is encoded with `nan`s

# temp[latIndexNearEquator] = 35

temp = data.isel(time=-1).thetao[0] # extract last timestep, elevation level 0

temp.plot(size=8, cmap="viridis", vmin=-10, vmax=35)

temp.coords # now coordinates are two-dimensional

In this plot we are using the 2D cell indices in x and y. If we want to plot in a non-Cartesian projection, we need to

use data.coords. However, this dataset's coordinate system is unusual: it is a tripolar grid. Ideally, something like

these lines should work -- but it does not:

# temp.plot(x="longitude", y = "latitude", size=8, cmap="viridis", vmin=-10, vmax=35)

# temp.plot.pcolormesh("longitude", "latitude")

So, this is an open question: how do you plot this dataset in an arbitrary projection using Cartopy?

My clumsy, very approximate solution:

temp.shape # 291x360

import numpy as np

tnew = xr.DataArray(

temp,

dims=("lat","lon"),

coords={"lat": np.linspace(-90,89.74176788,291), "lon": 73.5+np.linspace(0.01,359.99,360)}

)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14,12))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree()) # use this projection

ax.coastlines()

ax.gridlines()

tnew.plot(ax=ax, cmap="viridis", vmin=-10, vmax=35, transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(), cbar_kwargs={'shrink': 0.4})

# `transform` tells Cartopy the coordinate system of our data

In this lesson we'll work with bash command line, instead of the Jupyter notebook. We want to write a python script 'read.py' that takes a set of gapminder_gdp_*.csv files (one/few/many) as an argument and prints out various statistic (min, max, mean) for each year for all countries in that file:

$ ./read.py --min data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv # minimum for each year

$ ./read.py --max data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv # maximum for each year

$ ./read.py --mean data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv data-python/gapminder_gdp_asia.csv

It would be best to open two shells for the following programming, and keep nano always open in one shell.

Put the following into a file called read.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

print('argument is', sys.argv)

and then run it from bash:

$ chmod u+x read.py

$ ./read.py # it'll produce: argument is ['read.py'] (the name of the script is always there)

$ ./read.py one two three # it'll produce: argument is ['read.py', 'one', 'two', 'three']

Let's modify our script:

import sys

print(sys.argv[1:])

$ python read.py one two three # it'll produce ['one', 'two', 'three']

Let's modify our script:

import sys

for f in sys.argv[1:]:

print(f)

$ python read.py one two three # it'll produce one two three (one per line)

$ python read.py data-python/gapminder_gdp_*

$ python read.py data-python/gapminder_gdp_americas.csv data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv

$ python read.py data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv # same as last line

Let's actually read the data:

import sys

import pandas as pd

for f in sys.argv[1:]:

print('\n', f[26:-4].capitalize())

data = pd.read_csv(f, index_col='country')

print(data.shape, '\n')

$ python read.py data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv

$ wc -l !$ # the output should be consistent

Let's modify our script changing print(data.shape) -> print(data.mean()) to compute average per year for each file:

$ python read.py data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv

Let's add an action flag and calculate statistics based on the flag:

import sys

import pandas as pd

action = sys.argv[1]

for f in sys.argv[2:]:

print('\n', f[26:-4].capitalize())

data = pd.read_csv(f, index_col='country')

if 'continent' in data.columns.tolist(): # if 'continent' column exists

data = data.drop('continent',1) # delete it (1 stands for column, 0 for row)

if action == '--min':

values = data.min().tolist()

elif action == '--mean':

values = data.mean().tolist()

elif action == '--max':

values = data.max().tolist()

print(values,'\n')

$ python read.py --min data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv

$ python read.py --max data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv

$ python read.py --mean data-python/gapminder_gdp_{americas,europe}.csv

$ python read.py --mean data-python/gapminder_gdp_*.csv # should print data for all five continents

Let's add assertion for action (syntax is: assert n > 0.0, 'should be positive') right after the definition of action:

assert action in ['--min', '--mean', '--max'], 'action must be one of: --min --mean --max'

and try passing some other action.

Now let's package processing of a file (reading + computing + printing) as a function:

import sys

import pandas as pd

action = sys.argv[1]

assert action in ['--min', '--mean', '--max'], 'action must be one of: --min --mean --max'

filenames = sys.argv[2:]

def process(filename, action):

print('\n', filename[26:-4].capitalize())

data = pd.read_csv(filename, index_col='country')

if 'continent' in data.columns.tolist(): # if 'continent' column exists

data = data.drop('continent',1) # delete it (1 stands for column, 0 for row)

if action == '--min':

values = data.min().tolist()

elif action == '--mean':

values = data.mean().tolist()

elif action == '--max':

values = data.max().tolist()

print(values,'\n')

for f in filenames:

process(f, action)

Python scripts can process standard input. Consider the following script:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

for line in sys.stdin:

print(line, end='')

In the terminal make it executable (chmod u+x scriptName.py), and then run it:

./scriptName.py # repeat each line you type until Ctrl-C

echo one two three | ./scriptName.py # print back the line

cat file.extension | ./scriptName.py # process this file (filename=sys.stdin) from standard input

tail -1 scriptName.py | ./scriptName.py # print its own last line

Let's add support for Unix standard input. Delete 'print('\n', f[26:-4].capitalize())' and change the last two lines to:

if len(filenames) == 0:

process(sys.stdin,action) # process standard input

else:

for f in filenames: # same as before

print('\n', f[26:-4].capitalize())

process(f,action)

$ python read.py --mean data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv

$ python read.py --mean < data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv # anyone knows why this could be useful?

Here is why: you can do preprocessing in bash before passing the data to your Python script, e.g.

$ head -5 data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv | python read.py --mean # process only first five countries

cp data-python/gapminder_gdp_asia.csv a1

cat data-python/gapminder_gdp_europe.csv | sed '1d' >> a1 # add all European data without the header

cat a1 | python read.py --mean # merge Asian and European data and calculate joint statistics

Here is our full script:

import sys

import pandas as pd

action = sys.argv[1]

assert action in ['--min', '--mean', '--max'], 'action must be one of: --min --mean --max'

filenames = sys.argv[2:]

def process(filename, action):

data = pd.read_csv(filename, index_col='country')

if 'continent' in data.columns.tolist(): # if 'continent' column exists

data = data.drop('continent',1) # delete it (1 stands for column, 0 for row)

if action == '--min':

values = data.min().tolist()

elif action == '--mean':

values = data.mean().tolist()

elif action == '--max':

values = data.max().tolist()

print(values,'\n')

if len(filenames) == 0:

process(sys.stdin,action) # process standard input

else:

for f in filenames: # same as before

print('\n', f[26:-4].capitalize())

process(f,action)

Object-oriented programming is a way of programming in which you bundle related variables and functions into objects, and then manipulate and use these objects as a whole. We already saw many examples of objects on Python, e.g. lists, dictionaries, numpy arrays, that have both variables and methods inside them. In this section we will learn how to create our own objects.

You can think of:

- variables as properties / attributes of an object

- functions as some operations / methods you can perform on this object

Let's define out first class:

class Planet:

# internally we store all numbers in cgs units

hostObject = "Sun" # class attribute (the same value for every class instance)

def __init__(self, radius, mass): # sets the initial state of a newly created object

self.radius = radius*1e5 # instance attribute, convert km -> cm

self.mass = mass*1.e3 # instance attribute, convert kg->g

Let's define some instances of this class:

mercury = Planet(radius=2439.7, mass=3.285e23) # enter km and kg

venus = Planet(6051.8, 4.867e24) # enter km and kg

venus.radius, venus.mass, venus.hostObject

Instances are guaranteed to have the attributes that we expect.

Question: How can we define an instance without passing the values? E.g., I would like to say

earth=Planet()and then pass the attribute values separately like this:earth = Planet() earth.radius = 6371 # these are dynamic variables that we can redefine earth.mass = 5.972e24 Planet().radius # prints 'nan'

Let's add inside our class an instance method (with proper indentation):

def density(self): # it acts on the class instance

return self.mass/(4./3.*math.pi*self.radius**3) # [g/cm^3]

Redefine the class, and now:

earth = Planet()

earth.radius = 6371*1e5 # here we need to convert manually

earth.mass = 5.972e24*1e3

import math

earth.density() # 5.51 g/cm^3

Let's add another method (remember the indentation!):

def g(self): # free fall acceleration

return 6.67259e-8*self.mass/self.radius**2 # G in [cm^3/g/s^2]

and now

earth = Planet(6371,5.972e24)

mars = Planet(3389.5,6.39e23)

earth.g() # 981.7 cm/s^2

mars.g() / earth.g() # 0.378

Let's add another method (remember the indentation!):

def describe(self):

print('density =', self.density(), 'g/cm^3')

print('free fall =', self.g(), 'cm/s^2')

Redefine the class, and now:

jupyter = Planet(radius=69911, mass=1.898e27)

jupyter.describe() # should print 1.32 g/cm^3 and 2591 cm/s^2

print(jupyter) # says it is an object at this memory location (not very descriptive)

Let's add our last method (remember the indentation!):

def __str__(self): # special method to redefine the output of print(self)

return f"My radius is {self.radius/1e5}km and my mass is {self.mass/1e3}kg"

Redefine the class, and now:

jupyter = Planet(radius=69911, mass=1.898e27)

print(jupyter) # prints the full sentence

Important: As with any complex object in Python, assigning an instance to a new variable will simply create a pointer, i.e. if you modify one in place, you'll see the change through the other one too:

new = jupyter

jupyter.mass = -1

new.mass # also -1

If you want a separate copy:

import copy

new = copy.deepcopy(jupyter)

jupyter.mass = -2

new.mass # still -1

Let's create a child class Moon that would inherit the attributes and methods of Planet class:

class Moon(Planet): # it inherits all the attributes and methods of the parent process

pass

phobos = Moon(radius=22.2, mass=1.08e16)

deimos = Moon(radius=12.6, mass=2.0e15)

phobos.g() / earth.g() # 0.0001489

isinstance(phobos, Moon) # True

isinstance(phobos, Planet) # True - all objects of a child class are instances of the parent class

isinstance(jupyter, Planet) # True

isinstance(jupyter, Moon) # False

issubclass(Moon,Planet) # True

Child classes can have their own attributes and methods that are distinct from (i.e. override) the parent class:

class Moon(Planet):

hostObject = 'Mars'

def g(self):

return 'too small to compute accurately'

phobos = Moon(radius=22.2, mass=1.08e16)

deimos = Moon(radius=12.6, mass=2.0e15)

mars = Planet(3389.5,6.39e23)

phobos.hostObject, mars.hostObject # ('Mars', 'Sun')

phobos.g(), mars.g() # ('too small to compute accurately', 371.1282569773226)

One thing to keep in mind about class inheritance is that changes to the parent class automatically propagate to child classes (when you follow the sequence of definitions), unless overridden in the child class:

class Parent:

...

def __str__(self):

return "Changed in the parent class"

...

class Moon(Planet):

hostObject = 'Mars'

def g(self):

return 'too small to compute accurately'

deimos = Moon(radius=12.6, mass=2.0e15)

print(deimos) # prints "Changed in the parent class"

You can access the parent class namespace from inside a method of a child class by using super():

class Moon(Planet):

hostObject = 'Mars'

def parentHost(self):

return super().hostObject # will return hostObject of the parent class

deimos = Moon(radius=12.6, mass=2.0e15)

deimos.hostObject, deimos.parentHost() # ('Mars', 'Sun')

We already saw that in Python you can loop over a collection using for:

for i in 'weather':

print(i)

for j in [5,6,7]:

print(j)

Behind the scenes Python creates an iterator out of a collection. This iterator has a __next__() method, i.e. it does

something like:

a = iter('weather')

a.__next__() # 'w'

a.__next__() # 'e'

a.__next__() # 'a'

You can build your own iterator as if you were defining a function - this is called a generator in Python:

def square(x): # `x` is an input string in this generator

for letter in x:

yield int(letter)**2 # yields a sequence of numbers that you can cycle through

[i for i in square('12345')] # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

a = square('12345')

[a.__next__() for i in range(3)] # [1, 4, 9, 16, 25]

- comment your code as much as possible

- use meaningful variable names

- very good idea to break complex programs into blocks using functions

- change one thing at a time, then test

- use revision control

- use docstrings to provide online help

def average(values):

"Return average of values, or None if no values are supplied."

if len(values) > 0:

return(sum(values)/len(values))

print(average([1,2,3,4]))

print(average([]))

help(average)

def moreComplexFunction(values):

"""This string spans

multiple lines.

Blank lines are allowed."""

help(moreComplexFunction)

- very good idea to add assertions to your code to check things

assert n > 0., 'Data should only contain positive values'

is the same as

import sys

if n <= 0.:

print('Data should only contain positive values')

sys.exit(1)

- Python 3 documentation https://docs.python.org/3

- Matplotlib gallery http://matplotlib.org/gallery.html

- NumPy is a scientific computing package http://www.numpy.org

- SciPy is a rich collection of scientific utilities http://www.scipy.org/scipylib

- Python Data Analysis Library http://pandas.pydata.org

- list.sort() and list.index(value); heterogeneous lists

- to/from matplotlib, to/from numpy