Note to the reader: This blog post assumes some understanding of venture finance. If terms like “preferred stock” and “convertible debt” are new to you, we’d suggest reading a few primers first. For the definitive work on how VCs structure investments, we recommend Venture Deals by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson. Y Combinator also has an easy-to-digest guide on raising a Seed Round.

Trust is essential to supporting founders, who put it all on the line — and we believe transparency creates fertile soil for trust. It’s why we put our operating manual online, and it’s also why we’ve decided to publishthe documents we use as templates for our Series Seed and Convertible Note investments, as well as our side letters for Convertible Notes and Simple Agreements for Future Equity (SAFEs).

Transparency permeates every aspect of how we operate, including how we think about our focus on the future of work, what we look for in a startup, and how we make decisions.

We see publishing templates for our investment documents as a natural extension of this transparency. We hope they will give you a better sense of how we structure deals, [which terms we care about]((https://github.com/Bloomberg-Beta/Manual/blob/master/1%20-%20Manual.md#the-deal-terms), and a true-to-life taste of what it's like working with us. We want negotiation to be quick so founders can get back to building a company. We want to avoid wasting time negotiating points that are irrelevant in success and useless in failure. We also believe founders must understand every word of the contracts on which they build their business. We hope our explanations help — and that these templates snap us all to a useful grid.

In this post, we’ll share our thoughts on:

-

How to decide which type of investment to take;

-

Rights we ask for (and why we want them);

-

How we calculate a company’s price-per-share; and

-

Clarifying common misunderstandings about pro rata rights.

We stand on the shoulders of giants. We want to thank the organizations which have done our industry a service by creating (and publishing) the starting versions of these legal documents:

-

Our equity templates are based on Fenwick’s Series Seed documents which have been openly distributed for years. (Cooley has also contributed their own version.)

-

Our SAFE side letter accompanies Y Combinator’s updated SAFE documents. YC’s investment documents have continued to evolve, and we share their commitment to explain the structure behind our investments.

-

The National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) has published its forms since 2003. These documents are a great reference, and many of them serve as a useful standard in negotiations. However for the seed-stage deals where we invest, we find that a lighter-weight template is more appropriate.

It’s worth noting that many investment firms and law firms prefer to use their own versions of these documents. This can make closing a deal faster for investors (since they are already familiar with the terms), though diligent founders should ask what special terms a VC wants and why.

In almost every deal, founders face the choice of which investment instrument to use. Others have written at length on the differences between equity and notes (or SAFEs); we believe it’s ultimately up to the company to decide what works best. The rights we want are the same for all of our documents, so we keep their terms as similar to each other as possible. We’re happy to use whichever investment type the founders prefer.

That said, all things being equal we prefer equity because:

-

Founders and investors know how much of the company they own. We like the transparency and security of both parties knowing their respective ownership at the time of investment, without the “surprise” dilution that often comes when notes convert. This is particularly important when convertible securities are included in the pre-money valuation. (For a detailed breakdown of how this problem can trip up founders and investors, see the “Series Seed Documents” section of this post.)

-

Both sides agree on the valuation. One of the original benefits of the convertible note was that investors and entrepreneurs could defer the issue of valuation. These days, raising notes or SAFEs with a cap is essentially the same as raising a priced equity round (since the cap is almost always the same as the valuation the company would use if issuing equity, aka “the cap is the price”).

-

The company will end up issuing equity later anyway. It’s no longer the case that an equity financing is much slower (or more expensive) than issuing convertible notes. By issuing equity immediately, founders avoid kicking the legal can down the road and having a greater total cost of investment from a two-step deal.

-

Tax advantages through the Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) gain exclusion. Section 1202 of the Internal Revenue Code provides investors an opportunity to avoid tax on some or all of the gain realized from the sale of some startup equity held for more than five years. To qualify for this exlusion, an “interest” in a C corporation must be “stock” — many lawyers believe SAFEs don't qualify. (And while this tax advantage benefits us as investors, it has no direct benefit to founders — and also no cost.)

Nevertheless, there are some benefits to SAFEs and convertible notes:

-

The founders maintain more control (until the SAFE converts). We're fans of founder control. We generally avoid taking board seats, and prefer to be the folks founders have on speed dial if they ever need to talk through a problem. SAFEs and notes come with fewer strings attached, though when they convert into equity later then they can come with whatever governance provisions (rights of approval, etc.) that equity includes.

-

Increased flexibility in raising more before an initial equity offering. High resolution fundraising means that companies can raise smaller sums of money at various points along the way. It’s often easier to add another note to the cap table than to issue another round of priced equity. However, it’s worth pointing out that when companies raise notes at multiple valuations, later investors may include the shares from previous notes when calculating the company’s valuation — the note conversion price (see a similar issue in “The Convertible Note Shuffle” example below).

We’re also agnostic on whether founders should choose to raise using SAFEs or convertible notes. The distribution of our investments between SAFEs and notes has been almost exactly equal. Many investors already have their own templates for convertible notes, so they can often be the fastest way for companies to get from a handshake to a financing.

That said, SAFEs have taken a positive step towards standardizing startup fundraising. They address many of the issues associated with convertible notes (e.g., the “liquidation preference overhang”). What’s more, since a SAFE is not, technically, debt (it’s convertible equity), founders don’t need to worry about paying interest or maturity dates.

However, standard SAFEs leave out the full pro rata and information rights we care about (even with Y Combinator’s newly-issued side letter). Therefore, we typically issue our own side letter along with any SAFE we sign (unless it's a small, "flag" investment, in which case we use the Y Combinator side letter). For companies that use their own convertible note documents, we often issue a similar side letter.

We have based our Series Seed templates on Fenwick’s documents, with the following changes:

Many VCs ask startups to pay the legal costs incurred by the investors (in addition to the company’s own legal costs) when closing a round of financing. We believe legal fees are a cost of doing business and we pay our own attorneys.

Make clear that the pre-money valuation includes the option pool, SAFEs, and convertible securities — aka “the Convertible Note Shuffle”

There are two ways to calculate the pre-money valuation for a company that has SAFEs or notes: by looking just at the valuation of the company’s outstanding capital stock (i.e., ignore the SAFEs or notes), or by assuming those SAFEs and notes have converted (i.e., “include them in the pre-money valuation”). Like the “option pool shuffle,“ including convertible securities in the pre-money is equivalent to a tweak to the price in the next equity financing — because the price would otherwise be higher.

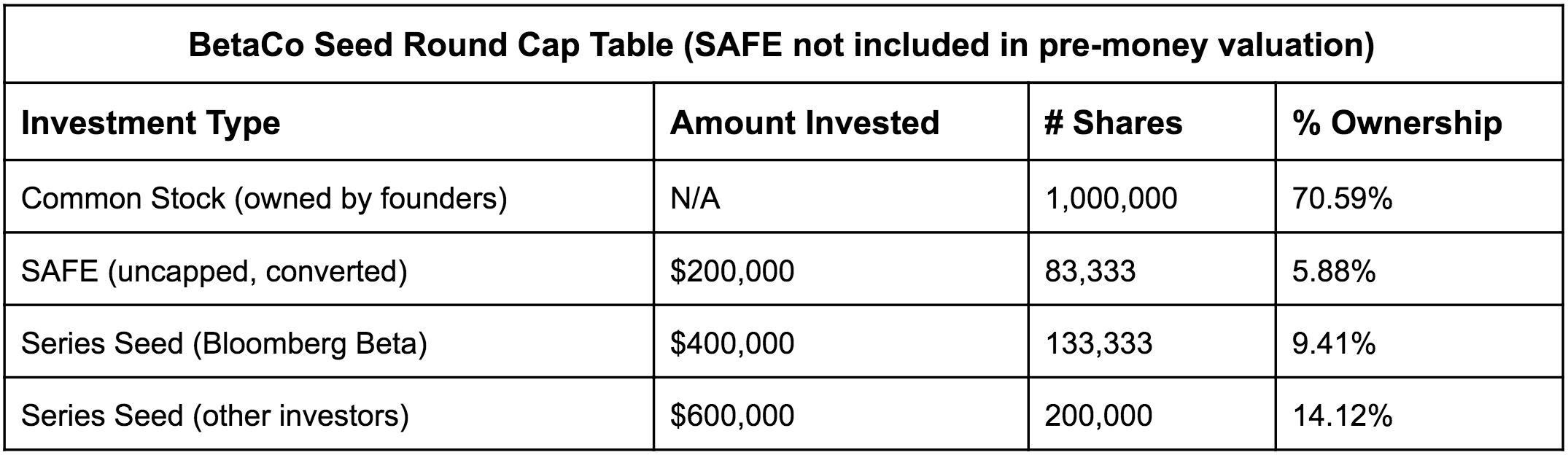

To explore this, meet our new (fictional) portfolio company, BetaCo. BetaCo has received a $200K uncapped SAFE from an angel investor with a 20% discount (a “discount-only” SAFE), and is raising $1M in the next equity financing at a $3M pre-money valuation. The cap table so far is simple (remember, the SAFE hasn’t yet converted into stock):

The post-money valuation of BetaCo will be $4M ($3M pre-money + $1M investment).

Now let’s assume Bloomberg Beta wants to invest $400K into BetaCo under two scenarios:

Scenario 1 — the SAFE is not included in the pre-money valuation:

-

Convert the SAFE with a 20% discount to get the purchasing power of the SAFE (a $200K note divided by 0.8 gives us an actualized value of $250K).

-

Since we are not including the SAFE in the pre-money valuation, the value of the company is fixed at $3M.

-

Divide this by the total number of shares (1,000,000) to get a price-per-share of $3M / 1,000,000 = $3.

-

This means that the SAFE holders get $250K / $3 = 83,333 shares.

-

Bloomberg Beta will get $400K / $3 = 133,333 shares.

-

The remaining Seed investors will get $600K / $3 = 200,000 shares.

-

However, the SAFE holders’ shares were not included in the original pre-money valuation, so the implied post-money becomes $4.25M ($3M pre-money + $1M raise + $250K implied value of SAFE).

In this case, even though the dollar value of the new investors’ shares is the same, both sets of investors have been diluted by the initial value of the SAFE. Here is the new cap table:

Scenario 2 — the SAFE is included in the pre-money valuation, watch the “convertible note shuffle” in action:

-

We convert the SAFE as above with the 20% discount, to get a true value of $250K.

-

Since we are including the SAFE in the pre-money valuation, we have to subtract the amount of the SAFE to find the true value of the company ($3M — $250K = $2.75M).

-

Divide this by the total number of shares (1,000,000) to get a price-per-share of $2.75.

-

The SAFE holder therefore gets $250K / $2.75 = 90,909 shares.

-

Bloomberg Beta gets $400K / $2.75 = 145,454 shares.

-

Any remaining Seed investors will get $600K / $2.75 = 218,181 shares.

The cap table now looks like this:

We prefer including convertible securities in the “pre” — Scenario 2 — because, intuitively, the capital invested to date helped build the value of the company (and most Series A investors assume this treatment). It also makes it easier for new investors to understand and negotiate their ownership stake.

ICOs and issuances of cryptocurrencies are a new and often effective method of raising capital — they can extend a startup’s runway without diluting shareholder ownership. However, if the founders personally hold tokens (other than through their ownership of their startup, which may also own tokens), then it’s easier for interests to become misaligned: the founders’ financial gains are now tied to the price of the token. Our Series Seed documents therefore now contain a protective clause which requires founders to ask for investor approval if their company issues a token (or the right to a future token) after we’ve invested.

We’ve included a side letter with practically all of the SAFEs we’ve signed. The same terms apply to all convertible notes we issue. That said, when we're a small minority investor, especially what we'd consider when we're writing a "flag check," we default to the standard YC side letter to keep things simple.

Pro rata rights give investors the ability to maintain their ownership stake by investing in a startup’s future fundraising rounds. As investors, we see these rights as a way of continuing to support our founders, and increasing our financial stake in investments we believe have outlier potential. The challenge is that SAFE holders get pro rata rights only in the round after they become preferred stockholders of the company. Y Combinator’s new side letter grants these rights in the equity financing when they convert, which is a step in the right direction, but SAFE holders still get diluted when companies issue SAFEs or convertible notes before the next equity round. We’ve even seen companies raise SAFEs on terms closer to a Series A (e.g., a $5M raise on a $35M valuation cap).

For example, imagine we make the very first investment in BetaCo using a $1M SAFE on a $10M post-money cap (with a target ownership of 10%). The initial cap table now looks like this:

After launching, the company raises an additional $2M SAFE from other investors at a $15M cap. Now the cap table is slightly more complicated:

Once the product gets traction, the company completes its first equity financing at a $25M pre-money valuation. The challenge is that we (as investors holding a SAFE at a $10M cap) do not have pro rata rights to maintain our 10% ownership in the SAFE raised at the $15M cap. By the time the Series A is raised at a $25M pre-money valuation, and both tranches of SAFEs convert, we will find our ownership lower than our target 10%.

Bloomberg Beta’s SAFE side letter addresses this issue by giving SAFE holders the right to purchase its pro rata portion of any instruments convertible into equity securities (to cover both SAFEs and convertible notes).

There are a variety of ways investors define pro rata rights, which can make it hard for a founder to know exactly what they are signing away. Many of these definitions revolve around what to include when calculating the overall value (“share capitalization”) of the company (the denominator when calculating pro rata share) — the larger the capitalization, the smaller the pro rata percentage. (The numerator is the number of as-converted shares that the investor owns in the company.) We’ve listed a few of the most common definitions below:

-

Fully Diluted Pro Rata (including unissued options): This is the broadest definition of share capitalization, and results in a lower pro rata percentage for an investor. When calculating an investor’s pro rata percentage under this definition, the denominator includes the entire capitalization of the company, including reserved (but unissued) shares. This is the definition YC uses in its SAFE side letter. Fully Diluted Pro Rata (excluding unissued options): This is similar to the first definition, but excludes unissued options reserved under a plan when calculating the total number of shares. Only outstanding securities are included in the denominator (both preferred and common, notes and SAFEs). As a result, an investor’s pro rata percentage is a little higher than it would be in the first case. This is the definition we typically see in our deals, and is what we use in our Series Seed templates.

-

Fixed Percentage Pro Rata: Some investors will specify in their investment documents they are entitled to X% of the next financing. We find this definition is the simplest, particularly when dealing with notes and SAFEs at different caps, when the calculations might get complicated. This is the definition we often use when issuing notes or SAFEs. We calculate our pro rata percentage based on our anticipated ownership after the financing, using the valuation cap of the note or SAFE.

-

Pro Rata Limited to Existing Investors: This definition is far less common (and more dangerous) than traditional pro rata treatments. In this case, investors are entitled to the same percent they invested in the current round. For example, if Bloomberg Beta invested $1M of a $2M round, we’d be have a pro rata of 50% in the next round — the denominator is entirely based on the securities held by the existing group of investors. If all investors receive these rights, then there may be nothing left to sell to new investors!

Our fund is set up so that any one of us is empowered to take risks fast and early. As a result, we are often the first institutional money invested in a company. To keep a level playing field for anyone investing at the same stage as us, our side letter gives us the right to any more favorable terms offered to a later investor.

When we invest in a company, we care about how the company is doing. However, SAFE holders are not entitled to receive any financial statements (balance sheets, income statements, etc.). To formalize the open relationships we aim to foster with our founders, we ask our portfolio companies to provide us with basic financial information on a regular basis. This includes the right to unaudited quarterly and annual financial statements. We also include a right to be notified of any legal proceedings that could materially and adversely affect the company.

YC’s SAFE does not include a minimum amount the company must raise in order to trigger the SAFE’s conversion into equity — a “Qualified Financing Threshold”. The threshold is designed to protect the investor against an insignificant equity round raised at an artificially high valuation.

Although this kind of insignificant raise is rare (we’ve only seen a handful of examples), we include a minimum financing threshold as protection to cover all notes and SAFEs we buy.

While many companies elect not to implement a major investor clause, we add language to ensure we maintain majority investor rights in the next equity financing in the instances they do.

As with our Series Seed documents, we ask for a protective clause requiring founders to ask for investor approval if their company issues any token (or the rights to a future token) after we’ve invested.

The point of having standard documents is to keep them standard except when it is truly essential to make a change. We’ve often seen lawyers who, thinking they’re doing the founders a favor, insert lots of “founder friendly” provisions that end up costing the company in legal fees and time spent negotiating. In our experience, founders don’t keep those lawyers around for long. We try to start with documents that are fair to founders and investors, and we only ask founders to do things that we would be happy to do in their shoes.

Ultimately these agreements revolve around trust, and we hope that in sharing them we are taking a step towards earning more of yours. As with everything we publish, these templates are living documents, so if there’s a way you think we could be doing things better, submit a pull request!

**Update (Apr ‘20): *To keep things simple in the event of an exit, we’ve added an increasingly common clause to our Series Seed documents which makes clear that Bloomberg Beta and its affiliates (e.g. Bloomberg LP itself) don’t need to change any existing contracts with the company, the acquirer, or their affiliates if those contracts are unrelated to the investment.

We highly recommend reading our detailed breakdown (above) of these documents before diving in, which outlines how the terms in these documents came about, and why we think they help align the interest of entrepreneurs and investors.

As with all content we publish, this repository is a living document, so please feel free to suggest any changes via a pull request!

- Convertible Note

- Note Purchase Agreement

- Term Sheet

- Side Letter (to accompany note documents that do not follow our template)