Kind of like there are many different styles to fashion, there are also various styles to coding such as imperative, functional, and object oriented. OOP is a popular coding paradigm that’s used by many software companies and a reason for this is that it helps make code more modular, facilitates code reuse, and makes the code base more maintainable. In this section you’ll learn how to do OOP programming in Python along with popular concepts such as classes, methods, inheritance, and polymorphism.

Let’s get our hands dirty and look at some code to gain a better example of how OOP works:

class Equations:

"""this class holds various mathematical equations."""

def polynomials(self,x,y,z):

return 5*x + 10*y + 2.5*z

>>> a1 = Equations()

>>> a1.polynomials(2,3,4)

50.0Believe it or not, there’s actually a lot happening in the above code snippet. One, the class is created with the class keyword and the class name must immediately follow the colon. Following the class name is the docstring which is a string that occurs as the first statement in a module, function, class, or method definition. The docstring is enclosed within triple quotes and lists the details about the class, and should be indented like a regular statement in Python. You can find out more details about the docstring convention in PEP-0008.

To create an instance of copy of the class use the following notation:

reference_variable = ClassName()Therefore, the following statements create several instances of the Equations class:

a = Equations()

b = Equations()

c = Equations()

d = Equations()

e = Equations()All of the above instances are of type Equations. To double check it here’s the following statement:

>>> type(a)

<class '__main__.Equations'>OK, so from the above example we’ve created two objects with the reference variable named a and b respectively. We have invoked the polynomials() method and both objects holds the same values. So, here’s a quick quiz for you. What do you think the following code will print?

if a == b:

print("Equal")

else:

print("Not Equal")Not Equal

I know it’s kinda tricky. Since these are two separate objects they’re not equal. When you’re using the == operator to compare objects you’re comparing their addresses in memory, not the value that they contain. For example, if you just type a or b in the terminal then you’ll get something like the following:

>>> a

<__main__.Equations object at 0x7f0bbbb83b38>

>>> b

<__main__.Equations object at 0x7f0bbb4cf2b0>If you want to compare their values then one way you can do this is by the following code snippet:

a1 = a.polynomials(1,2,3)

b1 = a.polynomials(1,2,3)

if a1 == b1:

print("Equal")

else:

print("Not Equal")Equal

The reason being is because you’re comparing their values not their addresses.

Since a class could have many objects, a convention to help keep track of them is useful. It’s important to know that self is a variable, not a keyword, so you could theoretically use another variable name instead. However, according to PEP 8 it’s always recommended to use self as other Python programmers will quickly understand what’s happening. This concept is better explained with some code.

class Humans:

"""Simple class for modeling humans."""

def first_name(first):

return first

def last_name(last):

return last

>>> name = Humans()

>>> name.first_name("Mike")Here’s the output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: first_name() takes 1 positional argument but 2 were givenWhat the heck? The error doesn’t make any sense because it says takes 1 positional argument but 2 were given. This compiler must be smoking some serious binary stuff because only one argument was provided, yet it claims two were. Let’s try something, let’s update the code so it includes the self keyword.

class Humans:

"""Simple class for modeling humans."""

def first_name(self, first):

return first

def last_name(self, last):

return last

name = Humans()

name.first_name("Mike")

'Mike'

name.last_name("Capone")

'Capone'OK, so the code now works. As you can see the way to fix this was to add self as the first parameter in all of the methods. To call or use a method you must use what’s known as dot notation. This is a style that’s popular in object oriented programming (OOP) languages and the dot means that it accesses a member of the class. You could also use the following notation to call a method of a class:

ClassName().method_name()A concrete example is listed below:

>>> Humans().first_name("Maria")'Maria'

There's some stuff happening behind the scenes. For example, when the method is called this is what’s going on:

class Humans:

"""Simple class for modeling humans."""

def first_name(jane, first):

return first

def last_name(jane, last):

return lastThe object that’s being referenced which is jane replaces self so that the compiler knows what object it’s working with. The self variable doesn’t do anything except just refer to an object, in this case jane.

The __init()__ method There’s a special method in Python that allows objects to be created with an initial state. This method is known as __init()__ which is short for initialization. This is similar to the constructor in other OOP languages like Java. Let’s use it to update the previous class so that we can create variables that can be used across the instance of a class. An example of it is listed below:

class Humans:

"""Simple class for modeling humans."""

def __init__(self,first,last):

self.first = first

self.last = last

def first_name(self):

return self.first

def last_name(self):

return self.last

def full_name(self):

return self.first + " " + self.last

>>> person = Humans("John", "Q")

>>> person.first_name()

'John'

>>> person.last_name()

'Q'

>>> person.full_name()

'John Q'A couple of modifications were made. One, the __init__() method was added which includes the parameters of self, first, and last. Inside the __init__() method the values of __init__() are initialized with the following statements:

self.first = first

self.last = lastThe statements mean to set the objects variable of first equal to first, and the object’s variable of last equal to the value of last. Remember, the self variable is needed so that we can keep track of the object we’re referencing. The rules of object oriented programming dictates that we can manipulate, add, delete, or access the data of a class. For example, we can add a new field by using the dot notation as follows:

person.occupation = "mechanic"To access the field use the dot notation again:

>>> person.occupation

'mechanic'To delete an attribute use the del statement:

>>> del person.occupationYou know it works as when you try to access the attribute it creates an error:

>>> person.occupation

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'Humans' object has no attribute 'occupation'You can also use the dot operator to modify the value of an attribute as shown below:

>>> person.first = "Johnny"

>>> person.first'Johnny'

Also, another way you could of implemented the full_name() method is as follow:

def full_name(self):

return self.first_name() + " " + self.last_name()This uses the self variable again to access the value of the method that’s associated with the object.

Now that we have a general idea on how OOP works in Python we can start designing some simple programs the OOP way. Let’s design a program that models a point in mathematics:

class Point:

"""Models a point in mathematics."""

def __init__(self,x,y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def getX(self):

return self.x

def getY(self):

return self.y

def get_point(self):

point = (self.x, self.y)

return point

>>> p1 = Point(1,2)

>>> p1.getX()

1

>>> p1.getY()

2

>>> p1.get_point()

(1, 2)Python allows inheritance which is a critical component of OOP. Inheritance is when a class receives the properties and methods of a class. Kind of like how a child inherits genes from their parents in the form of 23-chromosomes, subclasses or child classes can inherit attributes of a base class or parent. A simple example of inheritance is illustrated below:

class A:

"""I'm the base class.Bwahahaha."""

pass

class B(A):

"""I'm the child class."""

passIn the above example two classes named A and B are created. The two classes both contain the pass statements so they effectively do squat. The base class is A, and class B, the child class inherits from the parent class by using the syntax:

ChildClass(BaseClass):The above syntax is how you denote that inheritance is taking place. As stated earlier, with inheritance the child class retains the attributes and methods of the parent class. So, let’s test this by looking at some code:

class A:

"""I'm the base class.Bwahahaha."""

def message(self):

print("A")

class B(A):

"""I'm the child class."""

pass

>>> a1 = A()

>>> a1.message()

A

>>> b1 = B()

>>> b1.message()Ok, some updates were made to class A. Instead of simply containing a pass statement, it has a message() method which prints A. The child class is identical to the way it was before. An instance of A and B are created, and then the methods are invoked. When you call a1.message(), A is printed as expected. However, when you call b1.message(), A is also printed. This is somewhat unexpected as in the previous message there’s no method in its class. However, remember that all of the attributes and methods of the parent class is inherited by the child class therefore B can call any method that A has, but the reverse can’t be said.

Poly means many, and morphism means change or form. Combined together and poly + morphism translates into of many forms. One of the benefits of polymorphism is that it allows coders to specify methods in an abstract or general way, and then implement them in particular instances. Think of animals like dogs, bees, cats, cows, and horses. They are all animals and make sounds, but their sounds are all different. Let’s model this concept with some Python code:

class Animal:

def sound(self):

raise NotImplementedError("subclass must implement abstract method.")

class Dogs(Animal):

def sound(self):

pass

class Dogs(Animal):

def sound(self):

return "bark bark bark"

class Bees(Animal):

def sound(self):

return "buzz"

class Cats(Animal):

def sound(self):

return "meow"

class Horses(Animal):

def sound(self):

return "neigh"

class Cows(Animal):

def sound(self):

return "moo"

>>> d = Dogs()

>>> d.sound()

'bark bark bark'

>>> b = Bees()

>>> b.sound()

'buzz'

>>> c = Cats()

>>> c.sound()

'meow'

>>> h = Horses()

>>> h.sound()

'neigh'

>>> c = Cows()

>>> c.sound()

'moo'The base class is Animal and it contains a method named sound(). All of the subclasses extend the Animal class and override the method of sound() to implement their own version of it.

Encapsulation can be thought of as the art of data hiding. Encapsulation restricts access to methods and variables which prevents the data from being modified by accident and therefore makes the code more robust. Let’s model an extremely popular object that we use often which is our bank account:

class BankAccount:

"""A simple bank account class"""

def __init__(self,amount):

self.balance = amount

>>> account = BankAccount(1000000)

>>> account.balance

1000000The result is predictable right? That’s because the variable is public meaning that it can be accessed anywhere. Well, let’s change things up and do some modifications. It’s possible to emulate private and protected variables and methods in Python. You’ll need to use a process called name mangling:

class BankAccount:

def __init__(self, amount):

print("Inside the constructor")

self.__balance = amount

account1 = BankAccount(10000)

account1.__balance

>>> account1.__balance

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'BankAccount' object has no attribute '__balance'In this example a variable named __balance is created inside the constructor. When the constructor is called a message is printed and self.__balance is set to the value of amount. When a BankAccount object is made the value of 10000 is set to account1, and then account.__balance is accessed. The issue with this is that __balance is a private variable meaning that it can only be accessed by the class itself. The value of __balance can be accessed but the way you do this is by returning the value of the private variable through a method. An example of the updated code snippet is listed below:

class BankAccount:

def __init__(self, amount):

print("Inside the constructor")

self.__balance = amount

def getBalance(self):

return self.__balance

>>> account1 = BankAccount(10000)

Inside the constructor

>>> account1.getBalance()

10000You can also make variables protected in Python. This means that the variable could be accessed by the class itself, and subclasses. You denote a protected variable in Python by appending a single underscore at the beginning of the variable name as shown below in the following code snippet:

class BankAccount:

def __init__(self, amount):

print("Inside the constructor")

self.__balance = amount

def getBalance(self):

return self.__balanceMethods like variables can also be made private and protected, and just like their variable counterparts, you do this by modifying their name with double and single underscores respectively…

According to the Python docs the super keyword returns a proxy object that delegates method calls to a parent or sibling of a type. This can be beneficial when you need to access inherited methods that have been overridden in a child class. It can also be useful in a case of single inheritance when the parent class needs to be accessed without being named explicitly.

class ParentClass:

"""super() demo"""

def __init__(self, x, y, z):

self.x = x

self.y = y

self.z = z

print(self.x, self.y, self.z)

class SubClass(ParentClass):

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

print(self.x, self.y)

super().__init__(6,7,9)

>>> p = ParentClass(1,2,3)

1 2 3

>>> s = SubClass(4,5)

4 5

6 7 9In this example there’s a parent class along with its child class. The parent class contains a constructor which initializes three variables and then prints them. In the subclass there’s also a constructor which initializes two variables and then prints them. The subclass makes a call to the parent class’s constructor using the super() method, and three arguments are passed to it. The control flow goes to the parent class and then the code executes which results in the three variables being printed.

They’re many types of polygons, so many in fact that they can probably be explored in a separate book. To gain a better understanding of Polygons we’re going to model them in Python. Create a class named Polygon that contains the attributes for a polygon such as:

• number of sides • area • perimeter

Methods should be created that returns the values of each of these data. Therefore, the Polygon class should have three methods:

• number_of_sides() • area() • perimeter()

Then, create several subclasses that are concrete implementations of specific polygons. The polygons we’re going to model are:

• Triangle • Rhombus • Pentagon • Hexagon • Heptagon • Octagon • Nonagon • Decagon

Each of these polygons should represent a class of a corresponding name that provides a concrete implementation. Here are the details and formulas for the following polygons that should be translated into Python code.

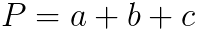

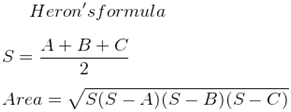

Triangle: A 3-sided polygon:

In Heron’s formula, S represents semi perimeter. This value is needed to plug into the second Area formula.

Rhombus: A 4-sided polygon:

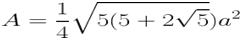

Pentagon: A 5-sided polygon:

The following formula is the area for a regular pentagon:

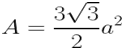

Hexagon: A 6-sided polygon:

The following formula is for a regular hexagon.

Heptagon: A 7-sided polygon:

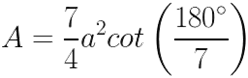

The following formula is for a regular heptagon.

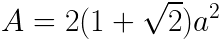

Octagon: An eight sided polygon:

The following formula is for a regular octagon.

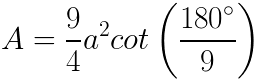

Nonagon: A nine sided polygon:

The following formula is for a regular nonagon.

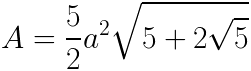

Decagon: A ten sided polygon:

The following formula is for a regular decagon.

Here are some test cases of what the output should look like when certain methods are ran:

tri = Triangle()

print("Triangle Area:", tri.area(5, 10))

print("Herons formula:", tri.herons_formula(5, 4, 3))

print("Perimeter:", tri.perimeter(20, 71, 90))

rho = Rhombus()

print("Rhombus Area:", rho.area(12.3, 83.9))

print("Perimeter:", rho.perimeter(5))

pent = Pentagon()

print("Pentagon Area:", pent.area(5))

print("Perimeter:", pent.perimeter(7.5))

hex = Hexagon()

print("Hexagon Area:", hex.area(5))

print("Perimeter:", hex.perimeter(11.25))

hep = Heptagon()

print("Heptagon Area:", hep.area(10))

print("Perimeter:", hep.perimeter(8))

oct = Octagon()

print("Octagon Area:", oct.area(10))

print("Perimeter:", oct.perimeter(7))

non = Nonagon()

print("Nonagon Area:", non.area(6))

print("Perimeter", non.perimeter(5))

dec = Decagon()

print("Decagon Area:", dec.area(10))

print(dec.perimeter(11.25))

Triangle Area: 25.0

Herons formula: 6.0

Perimeter: 181

Rhombus Area: 515.985

Perimeter: 20

Pentagon Area: 43.01193501472417

Perimeter: 37.5

Hexagon Area: 64.9519052838329

Perimeter: 67.5

Heptagon Area: 363.39124440015894

Perimeter: 56

Octagon Area: 482.84271247461896

Perimeter: 56

Nonagon Area: 222.5456709758244

Perimeter 45

Decagon Area: 769.4208842938134

112.5