-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 8

Iron age

This case study is about the use by art historians (Pr. Jean-Marc Luce and his Master students, CRATA Laboratory, University of Toulouse II, France) of our collaborative picture analysis software suite.

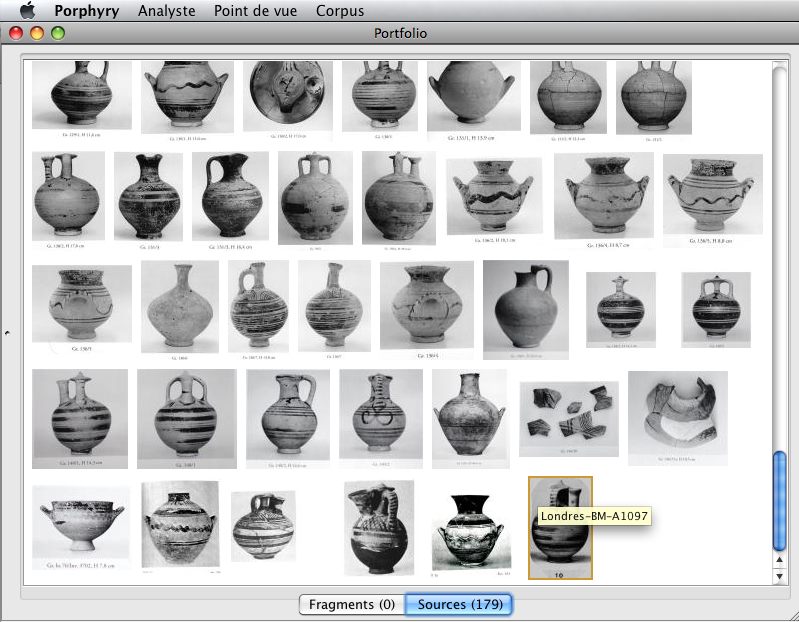

Fig. 1 – Vases photographs named after their storage location and inventory identifier

Fig. 1 – Vases photographs named after their storage location and inventory identifier

In this research project, the objects of study are Iron Age vases discovered in the excavations of the cemetery of Athens called "Kerameikos". These artifacts are documented with photographs named according to their storage location and inventory identifier (see Fig. 1).

The selected vases are particularly important for the understanding of the history of ancient Greece, since they are supposed to be from a short period (called "submycenaean") between the end of the Mycenaean civilization and the beginning of the Greek "dark ages". Indeed, invasions and external influences are supposed to have impacts on the styles the vases took, progressively making the forms simpler and the patterns more geometric.

A recent monograph analyzed features of each vase, and then gathered them into new coherent stylistic groups. In order to review this research work, Jean-Marc Luce used our software (see Fig. 2) to model "how [the], himself, classified it": "I didn't follow his analysis, [nor] all his headings. I just retained the groups".

Fig. 2 – Review of a researcher's hypotheses on stylistic groups

Fig. 2 – Review of a researcher's hypotheses on stylistic groups

Then, in order to initiate Master students to research, he asked each of them to analyse the stylistic features of one type of vases (see Fig. 3):

The tool is interesting for several reasons: [...] it introduces them to ceramics study; [...] it teaches how to "decorticate" and then recompose everything. When they do a dissertation on it they are "driven", they are forced to do a rigorous work.

Fig. 3 – Master student's analysis of stylistic features

Fig. 3 – Master student's analysis of stylistic features

Whether or not the tool really can structure the students, it seems that it is through dialoguing with their professor that they learn:

- how to identify a feature on a vase;

Professor: ``It is not a checker pattern. Zoom in."

- how to name a feature;

Student: ``I didn't know how to name it." Professor: ``Generally, one says ..."

- how to build a group;

Professor (to the observer): ``That's what one learns: combining features to get groups as coherent as possible." Professor (to the student): ``Your systems are fairly compatible, but not always coherent."

- how to interpret a group.

Professor: ``The patterns are varied. [They were] made by hand. It is the most ancient phase." Student: ``It's indeed what it seemed to me."

Fig. 4 – Submycenaean or transition to the next style?

Fig. 4 – Submycenaean or transition to the next style?

Fig.5 – End of mycenean or beginning of submycenean?

Fig.5 – End of mycenean or beginning of submycenean?

By comparing the viewpoints expressed in the new monograph and in an older one, the professor was able to guess that one of the innovations consisted in considering several vases (see Fig. 4) as belonging to a transitional phase towards a later period (`groupe 4') rather than being proper submycenaean. Another innovation consisted in considering vases (see Fig. 5), formerly tagged as from the end of the mycenean period (`HRIIIC récent'), as now being in fact submycenean (`groupe 1', `groupe 2').

Fig. 6 – Do your stylistic features define a group?

Fig. 6 – Do your stylistic features define a group?

Another use of viewpoints comparison was to confront Master students' interpretation and those of senior researchers. Even if the analysis by the student was incomplete and perfectible, the vases she described as having a flat paunch (`panse plate') and a short lip (`lèvre courte') appeared to be exactly what the specialist considered to be the oldest group (see Fig. 6). Moreover, she successfully identified features (oval paunch, flat lip, triangles or circles patterns) which were sufficient criteria to assign a vase to the more recent group. Indeed, as a Master student, comparing one's viewpoint with those of senior researchers should not be seen just as a way to get correct answers, but as a way to take part in the sense-making process followed by specialists, a way to get involved in the `on-going science'.

Aurélien Bénel, Chao Zhou, Jean-Pierre Cahier. Beyond Web 2.0... And Beyond the Semantic Web. In: Randall, David; Salembier, Pascal (Eds.). From CSCW to Web 2.0: European Developments in Collaborative Design. Springer Verlag. 2010. p. 155-171.