- Container's operations complexity

- Reference qualifires

- std::optional

- std::any

- Categories of Iterators

- Vector

- Deque

- Stack

- Queue

- Priority Queue

- Forward_List

- List

- HashTable

- The building pipeline

- GCC Compile Flags

- Pointers

- Lvalue vs Xvalue vs Rvalue

- Diamond inheritance problem

- Inheritance and Polymorphism

- Design Patterns

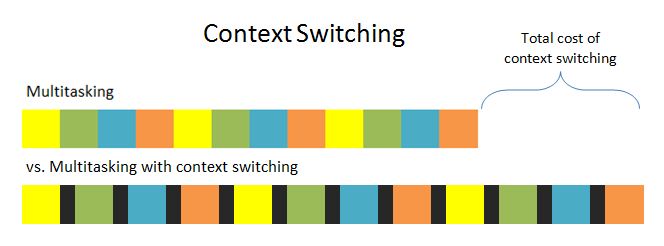

- Multithread Programming

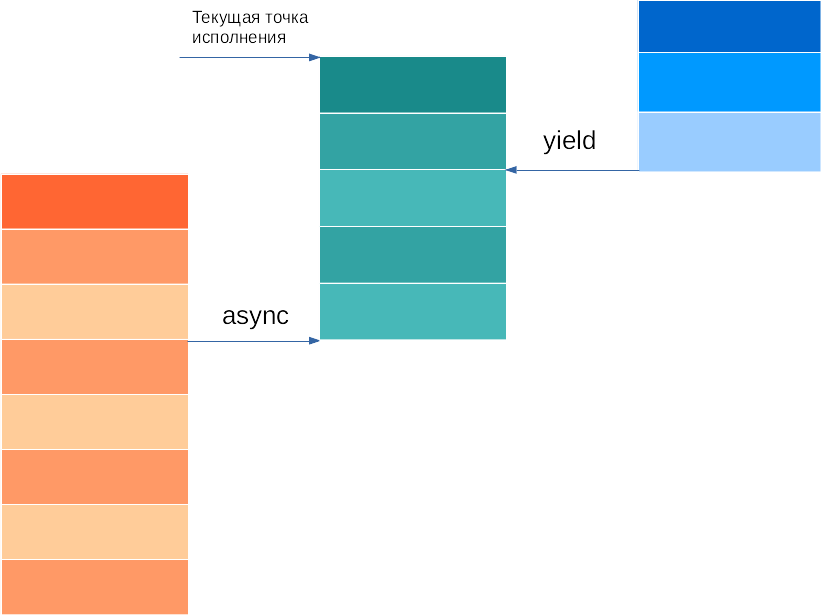

- Async Programming

- Exetrnal and Internal Linkage

- Hunter

- OSI

- Sources

| Container | indexing [] | push_back | insert | erase | find |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vector | O(1) | O(1) amort | O(N) | O(N) | none |

| deque | O(1) | O(1) amort | O(N) | O(N) | none |

| list / forward_list | none | O(1) | O(1) | O(1) | none |

| set / map | O(logN) | none | O(logN) | O(logN) | O(logN) |

| unordered_set / unordered_map | Q(1) mean | none | O(1) mean | O(1) mean | O(1) mean |

class A {

public:

void a() & {

std::cout << 1;

}

void a() && {

std::cout << 2;

}

};

int main() {

A a;

a.a();

A().a();

return 0;

}Output - 12

template<typename T>

class optional {

private:

static_assert(!std::is_const<T>::value, "bad T");

T value_;

bool has_;

public:

constexpr optional() noexcept: has_(false) {}

constexpr optional(std::nullopt_t) noexcept: has_(false) {}

constexpr optional(const optional &other) = default;

optional<T> &operator=(const optional<T> &) = default;

constexpr optional(optional &&other) noexcept: value_(std::move(other.value_)), has_(other.has_) {

other.value_ = T();

other.has_ = false;

}

optional<T> &operator=(optional<T> &&other) noexcept {

if (this != &other) {

value_ = std::move(other.value_);

has_ = other.has_;

other.value_ = T();

other.has_ = false;

}

return *this;

}

template<typename U = T>

optional<T> &operator=(U &&value) {

value_ = std::forward<U>(value);

has_ = true;

return *this;

}

T &operator*() {

return value_;

}

T *operator->() {

return &value_;

}

explicit operator bool() const {

return has_;

}

T &value() {

if (has_) {

return value_;

}

throw std::bad_optional_access();

}

template<class U>

T value_or(U &&default_value) {

if (has_) {

return value_;

}

return static_cast<T>(std::forward<U>(default_value));

}

};class Any {

private:

class Base {

public:

virtual Base *get_copy() const = 0;

virtual const std::type_info &get_type() const noexcept = 0;

virtual ~Base() {}

};

template<typename T>

class Derived : public Base {

public:

T value_;

template<typename U = T>

explicit Derived(U &&value) : value_(std::forward<U>(value)) {}

Base *get_copy() const override {

return new Derived<T>(value_);

}

const std::type_info &get_type() const noexcept override {

return typeid(T);

}

};

Base *data_;

template<class ValueType>

friend ValueType any_cast(const Any &operand);

template<class ValueType>

friend ValueType *any_cast(Any *operand) noexcept;

public:

Any() : data_(nullptr) {}

template<typename ValueType>

explicit Any(ValueType &&other) : data_(new Derived<ValueType>(std::forward<ValueType>(other))) {}

Any(const Any &rhs) : data_(rhs.data_->get_copy()) {}

template<typename ValueType>

Any &operator=(ValueType &&value) {

delete data_;

data_ = new Derived<ValueType>(std::forward<ValueType>(value));

return *this;

}

const std::type_info &type() const noexcept {

return data_->get_type();

}

~Any() {

delete data_;

}

};

template<class ValueType>

ValueType any_cast(const Any &operand) {

if (typeid(ValueType) != operand.type()) {

throw std::bad_any_cast();

}

return dynamic_cast<Any::Derived<ValueType> *>(operand.data_)->value_;

}

template<class ValueType>

ValueType *any_cast(Any *operand) noexcept {

if (operand != nullptr && operand->type() == typeid(ValueType)) {

return &dynamic_cast<Any::Derived<ValueType> *>(operand->data_)->value_;

}

return nullptr;

}| Name | Possibilities | Containers |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Input Iterator | Go through the content 1 time | std::istream |

| 2. Forward Iterator | ++ |

forward_list, unordered_map, unordered_map |

| 3. Bidirectional Iterator | ++, -- |

list, map, set |

| 4. Random Access Iterator | ++, --, +=, -=, <, >, it1 - it2 |

vector, deque |

template <typename Iter>

void Advance(Iter& iter, size_t shift) {

if (std::is_same_v<typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category, std::random_access_iterator_tag>) {

iter += shift;

} else {

for (size_t i = 0; i < shift; ++i, ++iter);

}

}Output - CE

Solution since C++11

template<typename Iter, typename IterCategory>

void AdvanceHandler(Iter& iter, size_t shift, IterCategory) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < shift; ++i, ++iter);

}

template<typename Iter>

void AdvanceHandler(Iter& iter, size_t shift, std::random_access_iterator_tag) {

iter += shift;

}

template <typename Iter>

void Advance(Iter& iter, size_t shift) {

AdvanceHandler(iter, shift, typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category());

}Solution since C++17

template<typename Iter>

void Advance(Iter &iter, size_t shift) {

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category, std::random_access_iterator_tag>) {

iter += shift;

} else {

for (size_t i = 0; i < shift; ++i, ++iter);

}

}template<typename Iter>

typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::difference_type Distance(Iter iter1, Iter iter2) {

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::iterator_category, std::random_access_iterator_tag>) {

return iter2 - iter1;

}

typename std::iterator_traits<Iter>::difference_type dist = 0;

for (; iter1 != iter2; ++iter1, ++dist);

return dist;

}template<typename Container>

class Back_insert_iterator {

private:

Container &container_;

public:

explicit Back_insert_iterator(Container &container) : container_(container) {}

Back_insert_iterator<Container> &operator++() {

return *this;

}

Back_insert_iterator<Container> &operator*() {

return *this;

}

Back_insert_iterator<Container> &operator=(const typename Container::value_type &value) {

container_.push_back(value);

return *this;

}

};

template<typename Container>

Back_insert_iterator<Container> Back_inserter(Container &container) {

return Back_insert_iterator<Container>(container);

}template<typename T>

class Vector {

};

template<>

class Vector<bool> {

private:

uint8_t *data_;

size_t size_;

size_t capacity_;

class BitReference {

private:

uint8_t *ptr_;

size_t shift_;

public:

explicit BitReference(uint8_t *ptr, size_t shift) : ptr_(ptr), shift_(shift) {}

explicit BitReference(uint8_t *ptr, size_t shift, bool state) : ptr_(ptr), shift_(shift) {

*this = state;

}

BitReference &operator=(bool b) {

if (b) {

*ptr_ |= (1u << shift_);

} else {

*ptr_ &= ~(1u << shift_);

}

return *this;

}

explicit operator bool() const {

return *ptr_ & (1u << shift_);

}

};

public:

Vector(size_t size, bool state) : data_(new uint8_t[size / 8 + 1]), size_(size / 8 + 1), capacity_(size / 8 + 1) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

BitReference{data_ + i / 8, i % 8, state};

}

}

BitReference operator[](size_t i) {

return BitReference{data_ + i / 8, i % 8};

}

~Vector() {

delete[] data_;

}

};template<typename T>

class Stack {

private:

struct Node {

T value_;

Node* next_;

};

Node* head_;

};template<typename T>

class Stack {

private:

T* data;

size_t head;

};template<class T>

class SafeStack {

private:

std::stack<T> data_;

std::mutex m_;

public:

T Pop() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lk(m_);

auto value = std::move(data_.top());

data_.pop();

return value;

}

void Push(const T &value) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lk(m_);

data_.push(value);

}

bool TryPop(T &value) {

if (m_.try_lock()) {

value = std::move(data_.top());

data_.pop();

m_.unlock();

return true;

}

return false;

}

};Stack is a LIFO data structure. It has methods push (by default it calls deque.push_back()) and pop (by default it calls deque.pop_back())

Similar to stack, but it's a FIFO data structure. Also has methods push (by default it calls deque.push_back()) and pop (by default it calls deque.pop_front())

template<class T>

class SafeQueue {

private:

std::queue<T> data_;

std::mutex m_;

public:

T Pop() {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lk(m_);

auto value = std::move(data_.front());

data_.pop();

return value;

}

void Push(const T &value) {

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lk(m_);

data_.push(value);

}

bool TryPop(T &value) {

if (m_.try_lock()) {

value = std::move(data_.front());

data_.pop();

m_.unlock();

return true;

}

return false;

}

};Similar to queue but it has logarithmic insertion and extraction, because of it stores objects in an orderly fashion, it allows to get the largest object for the constant time

template<typename T>

class ForwardList {

private:

struct Node {

T value_;

Node* next_;

};

Node* head_;

};How to reverse a forward list?

template<typename T>

class List {

private:

struct Node {

T value_;

Node* next_;

Node* prev_;

};

Node* head_;

};A preprocessor is a macro processor that transforms your program for compilation. At this stage, the work with preprocessor directives takes place. For example, the preprocessor adds headers to the code #include, removes comments, replaces macros #define with their values, selects the necessary pieces of code in accordance with the #if, #ifdef and #ifndef conditions.

Headers included in the program using the #include directive recursively go through the preprocessing stage and are included in the released file. However, each header can be opened several times during preprocessing, therefore, usually, special preprocessing directives are used to prevent circular dependencies.

Let's get the preprocessed code into the output file main.ii (files that have passed the preprocessing stage C ++ have the extension .ii) using the -E flag, which tells the compiler that there is no need to compile (more on that later) the file, but only preprocess it.

At this step, g++ performs its main task - it compiles, that is, it converts the code obtained in the previous step without directives into assembly code. It is an intermediate step between high-level language and machine (binary) code.

Assembly code is a human-readable representation of machine code.

Using the -S flag, which tells the compiler to stop after the compilation stage, we get the assembler code in the file.s output file.

Since x86 processors execute instructions in binary code, it is necessary to translate the assembly code into machine code using assembler.

Assembler converts assembly code into machine code by storing it in an object file.

An object file is an assembly-generated intermediate file that stores a piece of machine code. This piece of machine code, which has not yet been bundled together with other pieces of machine code into a final executable program, is called object code.

Further, it is possible to save this object code into static libraries in order not to compile this code again.

Let's get the machine code using assembler as into the file.o output object file.

The linker links all object files and static libraries into a single executable file, which we can run in the future. In order to understand how the linking occurs, you should talk about the symbol table.

A symbol table is a data structure created by the compiler itself and stored in the object files themselves. The symbol table stores the names of variables, functions, classes, objects, etc., where each identifier (symbol) is associated with its type, scope. Also, the symbol table stores the addresses of data and procedure references in other object files.

It is with the help of the symbol table and the links stored in them that the linker will be able to further build connections between data among many other object files and create a single executable file from them.

Sources:

- -Wpedantic (-pedantic) - checks that the code complies with the ISO C ++ standard, reports on the use of prohibited extensions, on the presence of extra semicolons, lack of line breaks at the end of the file, and other useful things

- -Werror - warning = error

- -Wall - turn on basic warnings

- -Wextra - turn on extra warnings

- -Wshadow - warn whenever a local variable or type declaration shadows another variable

- -Wnon-virtual-dtor - tells the compiler to issue a warning when a class appears to be polymorphic, yet it declares a non-virtual one

- Just a pointer

int a = 4;

int b = 1;

int *p = &a;

*p = 3;

p = &b;

*p = 2;

//there is no error- Pointer to const object

int a = 4;

int b = 1;

const int *p = &a; //it's equal to int const* p = &a;

//*p = 2; - this operation is unavailable because p is a pointer to const int

p = &b; // works fine- Const pointer to non const object

int a = 4;

int b = 1;

int *const p = &a;

*p = 2; //works fine

//++p; - this operation is unavailable because p is a const pointer to int- Const pointer to const object

int a = 4;

int b = 1;

const int *const p = &a;

/*

++p;

p = &b;

these operations are unavailable because p is a const pointer to const int

*/int8_t i8;

int64_t i64;

int8_t *p8 = &i8;

int64_t *p64 = &i64;

p8 += 10; //shift by 10 * sizeof(int8_t) bytes = 10 bytes

p64 += 10; //shift by 10 * sizeof(int64_t) bytes = 80 bytes;- Scooped Ptr - uncopyable, unmovable

Simple implementation

template<class T>

class scoped_ptr {

T *ptr_;

public:

explicit scoped_ptr(T *ptr) : ptr_(ptr) {}

~scoped_ptr() {

delete ptr_;

}

scoped_ptr(const scoped_ptr<T> &) = delete;

scoped_ptr(scoped_ptr<T> &&) = delete;

T *operator->() {

return ptr_;

}

T &operator*() {

return *ptr_;

}

T *get() {

return ptr_;

}

};

template<typename T, typename... Args>

T* make_scoped(Args &&... args) {

return new T(std::forward<Args>(args)...);

}- Weak Ptr - std::weak_ptr models temporary ownership: when an object needs to be accessed only if it exists, and it may be deleted at any time by someone else, std::weak_ptr is used to track the object, and it is converted to std::shared_ptr to assume temporary ownership. It has expired method to check whether the referenced object was already deleted

- Unique Ptr - uncopyable, movable

Simple implementation

template<class T>

class unique_ptr {

T *ptr_;

public:

unique_ptr() : ptr_(nullptr) {}

explicit unique_ptr(T *ptr) : ptr_(ptr) {}

~unique_ptr() {

reset();

}

unique_ptr(unique_ptr<T> &&other) noexcept: ptr_(other.ptr_) {

other.ptr_ = nullptr;

}

unique_ptr<T> &operator=(unique_ptr<T> &&other) {

if (this != &other) {

ptr_ = other.ptr_;

other.ptr_ = nullptr;

}

return *this;

}

void reset(T *ptr = nullptr) {

delete ptr_;

ptr_ = ptr;

}

T *release() {

auto ptr = get();

ptr_ = nullptr;

return ptr;

}

void swap(unique_ptr<T> &other) {

std::swap(ptr_, other.ptr_);

}

T *operator->() {

return ptr_;

}

T &operator*() {

return *ptr_;

}

operator bool() const {

return ptr_ != nullptr;

}

T *get() {

return ptr_;

}

};

template<typename T, typename... Args>

unique_ptr<T> make_unique(Args &&... args) {

return unique_ptr<T>(new T(std::forward<Args>(args)...));

}- Shared Ptr - copyable, movable (also has atomic reference counter)

Implementation

template <typename T>

class SharedPtr {

private:

T* ptr_;

std::atomic_uint* counter_;

public:

SharedPtr() : ptr_(nullptr), counter_(nullptr) {}

explicit SharedPtr(T* ptr) : ptr_(ptr), counter_(new std::atomic_uint(1)) {}

SharedPtr(const SharedPtr& r) : ptr_(r.ptr_), counter_(r.counter_) {

++*counter_;

}

SharedPtr(SharedPtr&& r) noexcept : ptr_(r.ptr_), counter_(r.counter_) {

r.ptr_ = nullptr;

r.counter_ = nullptr;

}

~SharedPtr() { reset(); }

auto operator=(const SharedPtr& r) -> SharedPtr& {

if (this != &r) {

reset();

counter_ = r.counter_;

++*counter_;

ptr_ = r.ptr_;

}

return *this;

}

auto operator=(SharedPtr&& r) noexcept -> SharedPtr& {

if (this != &r) {

reset();

counter_ = r.counter_;

ptr_ = r.ptr_;

r.ptr_ = nullptr;

r.counter_ = nullptr;

}

return *this;

}

// проверяет, указывает ли указатель на объект

explicit operator bool() const { return ptr_ != nullptr; }

auto operator*() const -> T& { return *ptr_; }

auto operator->() const -> T* { return ptr_; }

auto get() -> T* { return ptr_; }

void reset() {

if (counter_ == nullptr) {

return;

}

--*counter_;

if (*counter_ == 0) {

delete ptr_;

delete counter_;

}

ptr_ = nullptr;

counter_ = nullptr;

}

void reset(T* ptr) {

reset();

ptr_ = ptr;

counter_ = new std::atomic_uint(1);

}

void swap(SharedPtr& r) {

std::swap(ptr_, r.ptr_);

std::swap(counter_, r.counter_);

}

// возвращает количество объектов SharedPtr, которые ссылаются на тот же

// управляемый объект

auto use_count() const -> size_t {

return counter_ == nullptr ? 0u : static_cast<size_t>(*counter_);

}

};

template<typename T, typename... Args>

SharedPtr<T> make_shared(Args &&... args) {

return SharedPtr<T>(new T(std::forward<Args>(args)...));

}| Lvalue | Xvalue (expired value (also rvalue) since C++11) | Rvalue (Prvalue - pure rvalue) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identifiers: x; | 1. Literals: 5; 0.3f | |

| 2. = operation= (on primitives types) | 2. Binary operations (+, -, *, /, etc.) (on primitives types) | |

| 3. Prefix ++ -- (on primitives types) | 3. Postfix ++ -- | |

| 4. Unary * | 4. Unary &, +, - | |

| 5. Result of ?: (if both operands are lvalue) | 5. Result of ?: (if one of operands is rvalue | |

6. Result of , if rhs-operand is lvalue |

6. Result of , if rhs-operand is rvalue |

|

| 7. Result of function call (or method or custom operator call) if return type is a lvalue-reference | Result of function call (or method, or custom operator call) if return type is a rvalue-reference | 7. ... if return type isn't a reference |

| 8. The result of cast-expression if the result type is lvalue ref | Result of cast-expression if return type is rvalue-reference | 8. ... if the result if not a reference |

int main() {

int x;

int& rx = x;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

int x;

const int& rx = x;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

const int x = 0;

const int& rx = x;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

const int x = 0;

int& rx = x;

return 0;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

int& rx = 4;

return 0;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

const int& rx = 4;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

int x = 0;

int& rx = ++x;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

int x = 0;

int& rx = x++;

return 0;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

/*const*/ int&& rrx = 4;

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

int x;

/*const*/ int&& rrx = x;

return 0;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

int&& rrx1 = 0;

int&& rrx2 = rrx1;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

int&& rrx1 = 0;

int&& rrx2 = 1;

rrx2 = rrx1;

rrx1 = -1;

std::cout << rrx1 << ' ' << rrx2;

}Works, output - -1 0

int main() {

int x = 5;

/*const*/ int&& rrx = 4;

rrx = x; /*not initialization but assignment*/

std::cout << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 5

int main() {

int x = 5;

/*const*/ int&& rrx = 4;

rrx = x; /*not initialization but assignment*/

x = 6;

std::cout << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 5

int main() {

int&& rrx = 4;

int& rx = rrx;

std::cout << rx << ' ' << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 4 4

int main() {

int&& rrx = 4;

int& rx = rrx;

rx = 5;

std::cout << rx << ' ' << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 5 5

int main() {

/*const*/ int x = 4;

int &&rrx = 3;

rrx = x;

int &rx = rrx;

rrx = 6;

std::cout << x << ' ' << rx << ' ' << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 4 6 6

int main() {

int x = 1;

int& rx = x;

int&& rrx = rx;

return 0;

}Doesn't work

int main() {

int x = 1;

int& rx = x;

int&& rrx = std::move(rx);

return 0;

}Works

int main() {

int x = 1;

int& rx = x;

int&& rrx = std::move(rx);

rrx = 4;

std::cout << x << ' ' << rx << ' ' << rrx;

return 0;

}Works, output - 4 4 4

class A {

private:

int a;

public:

A() : a(4) {}

A(const A &other) : a(other.a) {

std::cout << "Copy A" << std::endl;

}

A(A &&other) noexcept: a(other.a) {

other.a = 0;

std::cout << "Move A" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

A &&a1 = A();

[[maybe_unused]] A a2(a1);

}Output - Copy A

class A {

private:

int a;

public:

A() : a(4) {}

A(const A &other) : a(other.a) {

std::cout << "Copy A" << std::endl;

}

A(A &&other) noexcept: a(other.a) {

other.a = 0;

std::cout << "Move A" << std::endl;

}

};

int main() {

A &&a1 = A();

[[maybe_unused]] A a2(std::move(a1));

}Output - Move A

P.S Example of usage comma operator

int a = 1, b = 2;

int i = (a += 2, a + b); // i = 5template<typename U>

void f(U&&) = delete;int& g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto r = g(x);

f<decltype(r)>();

return 0;

}r - int

int& g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto& r = g(x);

f<decltype(r)>();

return 0;

}r - int&

int& g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

// universal reference!!!

auto&& r = g(x);

f<decltype(r)>();

return 0;

}r - int&

const int& g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto& r = g(x);

f<decltype(r)>();

return 0;

}

r - const int&

template<typename U>

auto g(const U& u) {

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<U, int>) {

return 1;

} else { // else is necessary!!!

return 1.1;

}

}

int main() {

f<decltype(g(2))>();

return 0;

}int

template<typename U>

auto g(const U& u) {

if constexpr (std::is_same_v<U, int>) {

return 1;

} else { // else is necessary!!!

return 1.1;

}

}

int main() {

f<decltype(g(2.0f))>();

return 0;

}double

- if expr is not an identifier

- if expr is rvalue, then T

- if expr is lvalue, then T&

- if expr is xvalue, then T&&

int g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto r = g(x);

const decltype(r)& rr = x;

f<decltype(r)>();

f<decltype(rr)>();

return 0;

}int g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto r = g(x);

const decltype(x++)& rr = x;

f<decltype(r)>();

f<decltype(rr)>();

return 0;

}r - int, rr - const int&

int g(int& x) {

return x;

}

int&& h(int&& x) {

return std::move(x);

}

int main() {

int x = 4;

auto r = g(x);

decltype(h(3)) rr = x;

f<decltype(r)>();

f<decltype(rr)>();

return 0;

}CE

template <typename T, typename U>

auto g(const T& t, const U& u) -> decltype(t / u) {

return t / u;

}

int main() {

int u = 2;

f<decltype(g(2, 3))>();

return 0;

}int

template <typename T, typename U>

auto g(const T& t, const U& u) -> decltype(t / u) {

return t / u;

}

int main() {

int u = 2;

f<decltype(g(2, 3.0f))>();

return 0;

}float

It's equal to

template <typename T, typename U>

decltype(auto) g(const T& t, const U& u) {

return t / u;

}&+&=&&&+&=&&+&&=&&&+&&=&&

template<typename T>

std::remove_reference<T>&& move(T&& t) noexcept {

return static_cast<std::remove_reference<T>&&>(t);

}template<typename T>

T&& forward(std::remove_reference<T>& t) noexcept {

return static_cast<T&&>(t);

}class Product {

private:

size_t cost_;

size_t weight_;

public:

virtual ~Product() {}

virtual Product* create() = 0;

size_t cost() const { return cost_; }

size_t weight() const { return weight_; }

};

class Bread : public Product {

public:

Product* create() override {

return new Bread;

}

};

class Milk : public Product {

public:

Product* create() override {

return new Milk;

}

};A factory method defines a method that should be used instead of calling a new one to create product objects. Subclasses can override this method to change the type of products they create.

class Singleton {

private:

Singleton() {}

Singleton(const Singleton&) = delete;

Singleton& operator=(Singleton&) = delete;

public:

static Singleton& getInstance() {

static Singleton instance;

return instance;

}

};It's very simple to implement a single clumsy Singleton - you just need to hide the constructor and provide a static creating method. The same class behaves incorrectly in a multithreaded environment. Multiple threads can simultaneously call the Singleton's getter method and create multiple instances of the object at once.

class IObserver {

private:

std::string _name;

public:

explicit IObserver(const std::string& name) : _name(name) {}

virtual ~IObserver() {}

virtual void OnNotify() = 0;

};

class Log : public IObserver {

public:

Log() : IObserver("log_observer") {}

void OnNotify() override {

std::cout << "log\n";

}

};

class Physic : public IObserver {

public:

Physic() : IObserver("physic_observer") {}

void OnNotify() override {

std::cout << "physic\n";

}

};

class Audio : public IObserver {

public:

Audio() : IObserver("audio_observer") {}

void OnNotify() override {

std::cout << "audio\n";

}

};

class ISubject {

public:

enum class MessageType {

LOG_EVENT,

PHYSIC_EVENT,

AUDIO_EVENT

};

private:

using ObserversConatienr = std::vector<std::shared_ptr<IObserver>>;

std::unordered_map<MessageType, ObserversConatienr> _observers;

public:

virtual ~ISubject() {}

virtual void Attach(MessageType msg, const std::shared_ptr<IObserver>& observer) {

auto it = std::find(_observers[msg].begin(), _observers[msg].end(), observer);

if (it == _observers[msg].end())

_observers[msg].push_back(observer);

}

virtual void Detach(MessageType msg) {

if (_observers.count(msg) == 0 || _observers[msg].empty())

return;

_observers[msg].pop_back();

}

virtual void Notify(MessageType msg) {

if (_observers.count(msg) == 0)

return;

for (auto& o : _observers[msg])

o->OnNotify();

}

virtual void NotifyAll() {

for (auto& [key, value] : _observers)

for (auto& o : value)

o->OnNotify();

}

};

class Subject : public ISubject {};

int main() {

Subject s;

auto log = std::make_shared<Log>();

auto physic = std::make_shared<Physic>();

auto audio = std::make_shared<Audio>();

s.Attach(ISubject::MessageType::LOG_EVENT, log);

s.Attach(ISubject::MessageType::PHYSIC_EVENT, physic);

s.Attach(ISubject::MessageType::AUDIO_EVENT, audio);

s.NotifyAll();

s.Notify(ISubject::MessageType::LOG_EVENT);

return 0;

}Observer is a behavioral design pattern that creates a subscription mechanism that allows one object to watch and respond to events occurring in other objects.

class English {

public:

virtual std::string sayHello() const {

return "Hello";

}

};

class Spanish {

public:

std::string sayHello() const {

return "Hola";

}

};

class Adaptor : public English {

private:

Spanish *spanish_;

std::string translateToEnglish(const std::string& msg) {

// translation

return translatedMsg;

}

public:

Adaptor(Spanish *spanish) : spanish_(spanish) {}

std::string sayHello() const override {

auto spanishHello = spanish_->sayHello();

return translateToEnglish(spanishHello);

}

};

void EnglishSpeakingPerson(English* eng) {

// some code

}

int main() {

Spanish spanish;

Adaptor adaptor(&spanish);

EnglishSpeakingPerson(&adaptor);

return 0;

}The adapter acts as a layer between two objects, converting the calls of one into calls that are understandable to the other.

template<typename mutex>

class lock_guard {

private:

mutex &m_;

public:

explicit lock_guard(mutex &m) : m_(m) {

m_.lock();

}

lock_guard(mutex &m, std::adopt_lock_t) : m_(m) {}

lock_guard(const lock_guard &) = delete;

~lock_guard() {

m_.unlock();

}

};template<class Mutex>

class unique_lock {

Mutex *m_;

bool belongs_;

public:

unique_lock() : m_(nullptr), belongs_(false) {}

~unique_lock() {

if (belongs_) {

m_->unlock();

}

}

unique_lock(unique_lock &&other) noexcept: m_(other.m_), belongs_(other.belongs_) {

other.m_ = nullptr;

other.belongs_ = false;

}

explicit unique_lock(Mutex &m) : m_(&m), belongs_(true) {

m_->lock();

}

unique_lock(Mutex &m, std::defer_lock_t t) noexcept: m_(&m), belongs_(false) {}

unique_lock(Mutex &m, std::adopt_lock_t t) : m_(&m), belongs_(true) {}

void lock() {

if (!m_) {

throw std::system_error(EPERM, std::generic_category());

} else if (!belongs_) {

throw std::system_error(EDEADLK, std::generic_category());

}

m_->lock();

belongs_ = true;

}

void unlock() {

if (!m_) {

throw std::system_error(EPERM, std::generic_category());

}

m_->unlock();

belongs_ = false;

}

unique_lock<Mutex> &operator=(unique_lock<Mutex> &&other) {

if (this != &other) {

if (belongs_) {

unlock();

}

m_ = other.m_;

belongs_ = other.belongs_;

other.m_ = nullptr;

other.belongs_ = false;

}

return *this;

}

};A thread pool is a set of a fixed number of threads that are created when the application starts. Threads then sit and wait for requests coming to them, usually through a semaphore-driven queue. When a request is made and at least one thread is waiting, the thread wakes up, services the request, and returns to waiting on the semaphore. If no threads are available, requests are queued until one of them is available. Thread pools are generally a more efficient way to manage resources than just starting a new thread for each request. However, some architectures allow new threads to be created and added to the pool as the application runs, depending on the load on the request.

Asynchronous programming is a form of parallel programming that allows a unit of work to run separately from the primary application thread. When the work is complete, it notifies the main thread (as well as whether the work was completed or failed).

HandleConnection::pointer connection = HandleConnection::create(*ioService_);

acceptor_.async_accept(*connection->getSocket(),

boost::bind(&Server::handleAccept, this, connection,

boost::asio::placeholders::error));Essentially, coroutines are functions that have multiple entry and exit points.

def async_factorial():

result = 1

while True:

yield result

result *= i

fac = async_factorial()

for i in range(42):

print(next(fac))The program will print the entire sequence of factorial numbers numbered from 0 to 41.

The async_factorial() function will return a generator object that can be passed to the next() function, and it will continue executing the coroutine until the next yield statement while maintaining the state of all local variables of the function. The next() function returns what is passed by the yield statement inside the coroutine. Thus, the async_factorial() function in theory has multiple entry and exit points.

co_awaitA unary operator that allows, in general, to suspend the execution of a coroutine and transfer control to the caller until the calculations represented by the operand are completed;co_yieldA unary operator, a special case of the co_await operator, which allows you to suspend the execution of a coroutine and transfer control and the value of the operand to the caller;co_returnThe statement terminates the coroutine by returning a value; after the call, the coroutine will no longer be able to resume its execution.

More code

- https://blog.feabhas.com/2021/09/c20-coroutines/

- https://www.scs.stanford.edu/~dm/blog/c++-coroutines.html

Waiting for high-level coroutines in c++23...

Depending on the use of the stack, coroutines are divided into stackful, where each coroutine has its own stack, and stackless, where all local variables of the function are stored in a special object.

Since we can put the yield statement anywhere in coroutines, we need to save the entire function context somewhere, which includes the frame on the stack (local variables) and other meta information. This can be done, for example, by completely replacing the stack, as is done in stackful coroutines.

In the figure below, calling async creates a new stack frame and switches thread execution to it. This is practically a new thread, only it will be executed asynchronously with the main one.

yield, in turn, returns back the previous stack frame for execution, keeping a reference to the end of the current one on the previous stack.

int value = 0;

void f() {

++value;

}

int main() {

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

for (size_t i = 0; i < 20; ++i) {

threads.emplace_back(f);

}

for (auto&& thread : threads) {

thread.join();

}

std::cout << value;

return 0;

}Output - who knows...

std::atomic<int> value = 0;

void f() {

++value;

}

int main() {

std::vector<std::thread> threads;

for (size_t i = 0; i < 20; ++i) {

threads.emplace_back(f);

}

for (auto&& thread : threads) {

thread.join();

}

std::cout << value;

return 0;

}Output - 20

Atomicity means the indivisibility of an operation. This means that no thread can see the intermediate state of the operation, it is either in progress or not. If you are using std::atomic<> from a non-trivial template, then most likely this will lead to using standard std::mutex

Most common methods:

load()atomically obtains the value of the atomic objectstore()atomically replaces the value of the atomic object with a non-atomic argumentexchange() = store() + load()atomically replaces the value of the atomic object and obtains the value held previouslycompare_exchange_weak()atomically compares the value of the atomic object with non-atomic argument and performs atomic exchange if equal or atomic load if not

The difference between compare_exchange_weak and compare_exchange_strong is that compare_exchange_weak on some platforms may fail falsely (i.e. return false and fail to exchange even if the values are equal). compare_exchange_strong calls compare_exchange_weak in a loop. When compare_exchange_strong is called in a loop it makes sense to use compare_exchange_weak to avoid nested loops. A very important point is that all operations on atomic types in C ++ 0x are sequentially consistent by default, i.e. all operations with atomic types are performed and observed by other processors in the order in which they were written.

Lock-free - lock-free is the procedure for which the progress of at least one thread performing this procedure is guaranteed. Other threads can wait, but at least one thread must progress.

Wait-free - an operation is called wait-free if it completes in a certain number of steps that do not depend on the state and actions of other threads.

template<typename T>

class Stack {

private:

struct Node {

std::shared_ptr<T> value_;

Node *next_;

explicit Node(const T &value, Node *next = nullptr) : value_(std::make_shared<T>(value)), next_(next) {}

};

std::atomic<Node *> head_;

std::atomic<Node *> need_delete_;

std::atomic<size_t> threads_in_pop_;

void append_list_to_be_deleted(Node *begin, Node *end) {

end->next_ = need_delete_;

while (!need_delete_.compare_exchange_weak(end->next_, begin));

}

void append_list_to_be_deleted(Node *begin) {

auto end = begin;

while (end->next_) {

end = end->next_;

}

append_list_to_be_deleted(begin, end);

}

void delete_nodes(Node *node) {

while (node) {

auto next = node->next_;

delete node;

node = next;

}

}

void try_delete(Node *node) {

if (threads_in_pop_ == 1) {

auto nodes_to_be_deleted = need_delete_.exchange(nullptr);

if (--threads_in_pop_ == 0) {

delete_nodes(nodes_to_be_deleted);

} else if (nodes_to_be_deleted) {

append_list_to_be_deleted(nodes_to_be_deleted);

}

delete node;

} else {

append_list_to_be_deleted(node);

--threads_in_pop_;

}

}

public:

Stack() : head_(nullptr), need_delete_(nullptr), threads_in_pop_(0) {}

void push(const T &value) {

Node* new_node = new Node(value, head_.load());

while (!head_.compare_exchange_weak(new_node->next_, new_node));

/*

* if (head_ == new_node->next_) {

* head_ = new_node;

* return true;

* }

* new_node->next_ = head_;

* return false;

*/

}

std::shared_ptr<T> pop() {

++threads_in_pop_;

auto old_head = head_.load();

while (old_head && !head_.compare_exchange_weak(old_head, old_head->next_));

/*

* if (head_ == old_head) {

* head_ = old_head->next_;

* return true;

* }

* old_head = head_;

* return false;

*/

std::shared_ptr<T> res;

if (old_head) {

res.swap(old_head->value_);

}

try_delete(old_head);

return res;

}

~Stack() {

delete_nodes(head_);

}

};Sources

- http://cppjournal.blogspot.com/2010/11/lock-free-1.html

- http://cppjournal.blogspot.com/2010/11/lock-free-2.html

Now, the ABA problem is an anomaly where Compare and Swap approach alone fails us.

Say, for example, that one activity reads some shared memory (A), in preparation for updating it. Then, another activity temporarily modifies that shared memory (B) and then restores it (A). Following that, once the first activity performs Compare and Swap, it will appear as if no change has been made, invalidating the integrity of the check.

While in many scenarios this doesn’t cause a problem, at times, A is not as equal to A as we might think.

Let’s think about a multithreaded scenario when Thread 1 and Thread 2 are operating on the same bank account. When Thread 1 wants to withdraw some money, it reads the actual balance to use that value for comparing the amount in the CAS operation later. However, for some reason, Thread 1 is a bit slow — maybe it’s blocked.

In the meantime, Thread 2 performs two operations on the account using the same mechanism while Thread 1 is suspended. First, it changes the original value, which has already been read by Thread 1, but then, it changes it back to the original value.

Once Thread 1 resumes, it will appear as if nothing has changed, and CAS will succeed:

Sources

A translation unit refers to an implementation (.c/.cpp) file and all header (.h/.hpp) files it includes. If an object or function inside such a translation unit has internal linkage, then that specific symbol is only visible to the linker within that translation unit. If an object or function has external linkage, the linker can also see it when processing other translation units. The static keyword, when used in the global namespace, forces a symbol to have internal linkage. The extern keyword results in a symbol having external linkage.

The compiler defaults the linkage of symbols such that:

- Non-const global variables have external linkage by default

- Const global variables have internal linkage by default

- Functions have external linkage by default

Lets quickly discuss the difference between declaring a symbol and defining a symbol: A declaration tells the compiler about the existence of a certain symbol and makes it possible to refer to that symbol everywhere where the explicit memory address or required storage of that symbol is not required. A definition tells the compiler what the body of a function contains or how much memory it must allocate for a variable.

Situations where a declaration is not sufficient to the compiler are, for example, when a data member of a class is of reference or value (as in, neither reference nor pointer) type. At the same time, it is always allowed to have pointers to a declared (but not defined) type, because pointers require fixed memory capacity (e.g. 8 bytes on 64-bit systems) and do not depend on the type pointed to. When you dereference that pointer, the definition does become necessary. Also, for function declarations, all parameters (no matter whether taken by value, reference or pointer) and the return type need only be declared and not defined. Definitions of parameter and return value types only become necessary for the function definition.

// declarations

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

// definition

int f() {

std::cout << "I'm f()";

}

int main() {

f();

return 0;

}Output - I'm f()

// declarations

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

int f();

// definitions

int f() {

std::cout << "I'm f()";

}

int f() {

std::cout << "I'm also f()";

}

int main() {

f();

return 0;

}Output - CE (due to ODR)

class A;

class B {

private:

A* a;

};We don't care about the definition of class A, because pointers have fixed size

In C++ there exists the concept of forward declaring a symbol. What we mean by this is that we declare the type and name of a symbol so that we can use it where its definition is not required. By doing so, we don’t have to include the full definition of a symbol (usually a header file) when it is not explicitly necessary. This way, we reduce dependency on the file containing the definition. The main advantage of this is that when the file containing the definition changes, the file where we forward declared that symbol does not need to be re-compiled (and therefore, also not all further files including it).

class A;

void f (A& a) {

// some code

}By forward declaring A, the only files requiring recompilation are a.hpp and f.cpp (assuming that’s where f is defined).

header.hpp

int x = 5;main.cpp

extern int x;

int main() {

std::cout << x;

return 0;

}header.hpp

void f() {

std::cout << "I'm f()";

}first.cpp

#include <header.hpp>

/*other code*/

second.cpp

#include <header.hpp>

/*other code*/

The linker found two definitions for the same symbol f. Because it had external linkage, f was visible to the linker when processing both first.cpp and second.cpp. Naturally, this violates the One-Definition-Rule, so this causes a linker error.

header.hpp

static int x = 10;first.hpp

void f1();second.hpp

void f2();first.cpp

#include <header.hpp>

void f1() {

x = 11;

}second.cpp

#include <header.hpp>

void f2() {

x = -11;

}main.cpp

#include <header.hpp>

#include <first.hpp>

#include <second.hpp>

int main() {

f1();

f2();

std::cout << x;

return 0;

}Output - 10

Sources:

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cpp-pm/gate/master/cmake/HunterGate.cmake -O cmake/HunterGate.cmakeThe goal is to represent bits of information as signals

- Bandwidth

- Delay

- Number of errors

Targets:

- Defining the start / end of a frame in a bitstream

- Error detection and correction

If the network architecture allows multiple access to the communication channel:

- Addressing

- Consistent channel access

1. Specify the number of bytes of the frame

Advantages:

- Easy to implement

Disadvantages:

- 1 error -> reading sequence out of order

2. Inserting bytes and bits

The beginning and end of each frame are marked with special sequences of bytes and bits

Examples:

- BSC protocol (DLE STX (Start of Text) | DLE ETX (End of Text))

- HDLC and PPP (01111110 - start and end of the frame)

3. Physical layer facilities

Preamble (Ethernet):

- Length = 8 bytes

- The first 7 bytes = 10101010

- The last bytes = 10101011

Transmitting an unused character (fast Ethernet):

- The beginning of the frame - J (11000) and K (10001)

- The end of the frame - T (01101)

- Error detection

- Check sum

- Error correction

- Error correction codes (with redundant information)

- Resending data

- If an error is found in the frame or it did not reach the recipient, it can be sent again

Resending data model (Stopping and waiting)

There is also a sliding window technology used in the transport layer of the TCP protocol.

Sources:

- A.A. Borodin's lectures

- C++ ФПМИ 1 курс

- Video of some Indian from YouTube