This is a guide containing tools and tricks every developer starting on the open source journey will need. It can also serve as a quick reference for some of the tricky commands for the pros. Feel free to suggest changes or contribute!

Starting your own project with others? Learn about the [Basic Workflow](https://github.com/chhavip/Git-Guide/blob/master/Basic%20Workflow.md) when working on collaborative projects.

##Table of Contents:

##Common Terms Some of the basic terms used while working with git are:

-

Repository : A basic folder or a collection of files that represents one project. The name of this repository is Git-Guide. When you clone, you clone an entire repository and every repository is identified by a unique URL.

-

Local Repository : The project folder which exists in your machine, locally. It is where you make your changes and push them to the github repository. No one can make changes to your local repository directly other than yourself, you need to sync (connect) this local repository with a repository on github (or any VCS system) in order to push and pull changes.

-

Remote Repository : This is the respository hosted on github (or any other VCS) to which your local repository is connected. You push your changes to this and others working on the same project can see your changes. Only those with write permissions to this repository can make direct changes to it. Many people can make changes to this repository and you can pull those changes to your local repository and push your own to this. A single local repository can be connected to multiple remote repositories. Remote repositories are referred by keywords like origin and upstream.

-

Fork: This is how you make a copy of a project owned by someone else. A person or organisation. Apart from the owner of the repository, no one is allowed to make direct changes to the project. So fork is used to make a copy of the project that is owned by you.

-

Clone: You got the project in your account, now what? A clone is just that, a copy. It does not care about ownership. It is aimed to bring the copy of the project hosted on github or any other VCS system in your machine. This is where you will make the changes and later update your remote project

-

Commit: This is a checkpoint in your project history. All the commits are recorded in git logs with the description provided by user. After you add, modify or remove any files, a commit is made to save these changes in history.

-

Push: This is how you send the changes made in your local repository to your remote. All your changes remain unsynced until you have pushed them and this is necessary step to keep the changes parallel. Only the files you commit(as in the previous definition) are pushed and rest of the changes remain local to your project.

-

Fetch: This is in very simple terms means to download any updates and changes from a remote repository. This does not mean that you have included the changes in your project. Just download.

-

Merge: This means to merge or combine updates fetched from remote repository with your local one. This may lead to merge conflicts if a change in remote is incompatible with a change in your local project.

-

Pull: This means to fetch any updates that may have occured in a remote branch in your local repository and merge them. This is basically a fetch followed by a merge.

-

Pull Request (PR): Pull Request or PR as it is generally known, is a method to contribute to open development projects by including bug fixes or adding new features. Its a way of contributing by asking the owner of project to include changes made in the external/forked repository.

##Set Up In order to set up the user through terminal:

git config --global user.name <name>

git config --global user.email <email>

This is the user your commits and PR will be shown through.

##Forking a Project and Making Changes In order to work on an existing project that is not owned by you, follow the following steps:

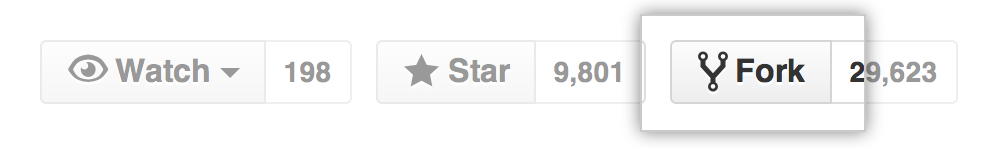

Forkthe project from the respective repository. This will redirect you to your fork of the project which is basically a copy of the original project but you are its owner.

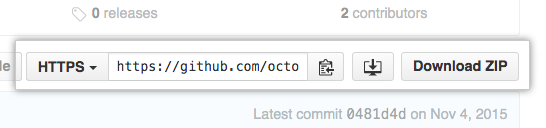

- Copy the HTTPS link of the project and go to the location through terminal or command prompt where you want to have the repository locally

- Run

git clone <link to your fork>. This will give you a local copy of the project which you can work with.

- Any changes in the local repository can be tracked by running

git statusin that directory. Files in red will be the ones that have been modified, added or deleted. - To have your remote repository(the one hosted online also referred to as origin) reflect the changes, do

git add <file-path>for all the files who's changes you wish to see in the remote. You can also rungit add .to add all the files that have been changed (not advisable though). - Run

git statusonce again and you will see the files that you have added in green. - In case you need to un-add any file, run

git reset HEAD -- <file path> - To commit the changes (equivalent to locking down the changes you have made), run

git commit -m "Your commit message" - So far you have made and saved the changes in your local repository, to send the changes to your fork in github, run

git pushwhich will ask for your username and password. Fill and you are ready to go.

NOTE: This by default pushes all your local branches to remote with the same name. We will go through branching later.

##Setting up Upstream

When a repository is cloned, it has a default remote called origin that points to your fork on GitHub, not the original repository it was forked from. To keep track of the original repository, you should add another remote named upstream:

-

Open terminal or git bash in your local repository and type:

git remote add upstream <url of original project> -

Run

git remote -vto check the status, you should see something like the following:

origin https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/project-name.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/YOUR_USERNAME/project-name.git (push)

upstream https://github.com/OWNER_USERNAME/project-name.git (fetch)

upstream https://github.com/OWNER_USERNAME/project-name.git (push)

-

To update your local copy with remote changes, run the following:

git fetch upstreamgit merge upstream/masterAs you may have guessed already, quicker way to the same would be

git pull upstream master, because Pull is essentially a Fetch operation followed by Merge operation.This will give you an exact copy of the current remote, but make sure you don't have any local changes.

##Branching and Pull Requests

Branches exist in github to enable you to work on different features simultaneously without they interfering with each other and also to preserve the master branch. Usually the master branch of your project should be kept clean and no feature should be developed directly in the master branch. Follow the following steps to create branches and be able to sync them:

-

Make sure you are in the master branch :

git checkout master. -

Sync your copy with remote copy :

git pull. -

Create a new branch with a meaningful name :

git checkout -b branch_name. -

Add the files you changed :

git add file_name(avoid usinggit add .). This is called "staging" the files. -

Commit your changes

git commit -m "Message briefly explaining the feature". -

Push to your repo

git push origin branch-name

This will push the changes you made to your fork on github under the branch name you gave.

To have the owner of the original project review your changes, create a Pull Request explaining the changes you made. If it is satisfactory, it will be merged with the original project.

###Common Branch Commands:

git branch will give you all the branches your local repository has.

git branch -a will give you all the branches your local and remote repositories have

git branch -d the_local_branch will delete a local branch that you had by the given name. Make sure you dont have any loose ends in the branch or a delete won't be allowed.

After deleting the local branch, if you wish to delete the remote branch of the same name, use:

git push origin :the_remote_branch but be careful while using this.

##Squashing Commits Often it is required while contributing that your entire feature change is in the form of one single commit, this is where squashing comes in. Be aware of the type of commits you are trying to squash. There can be two:

- Commits in your local repository

- Commits you have already pushed to remote

First of all be sure to run git log and see your recent commit history, this will help you decide which commits you wish to squash.

If for example you wish to squash the last two commits into a single one, run:

git checkout my_branch to make sure you are on your required branch

git reset --soft HEAD~2 where 2 represents the number of commits to be sqaushed, can be replaced with your need

git commit -m "New commit message to represent the squashed commits"

The above two instruction will locally squash the number of commits you chose to. In case you had already pushed the commits to your remote repository, run the following command to make your remote reflect the changes:

git push --force origin my_branch

This is a forced update that makes the remote repository squash the commits into one.

###Fixing PR when other changes get Merged leading to Conflicts

This is in continuation with requirement of having a single commit in your PR, suppose you did some work and submitted a PR to the main repository but before your request could be merged, changes were made by other developers in the repository and now your PR presents merge conflicts. You could fetch the work, resolve merge conflicts and push again but that will lead to MERGE COMMIT that is undesirable at times. The flow below can be followed to prevent the same:

This assumes the following:

- You have submitted a PR for a feature

- Changes have been made to remote before your PR got merged and now there are merge conflicts between your PR and remote

The steps to follow:

- Checkout your branch with the features required

git checkout my_branch - Fetch changes from remote

git fetch upstream - Stash local changes(if any)

git stash - Rebase to the latest branch in upstream (let it be master in our case)

git rebase upstream/master - The following two steps are required only if merge conflicts occur:

- If any merge conflicts are occuring, fix them in the project then add the files by using

git add <file name>orgit checkout -- <file name>(if you dont want your local changes) - After the changes have been fixed run

git rebase --continue - Now the remote changes have been applied and your work has been applied on top of it

- Force push to your branch to update the PR by using

git push --force origin my_branch

##Undoing Commits Undoing commits means to remove the last commit you made from your history tree. This is not needed usually but more in the case a commit was made by mistake or was not complete. The following steps should usually be followed before having pushed to remote repository but you can force push your changes to reflect them on the remote. Now, getting down to undoing commits and the different scenarios:

A-B-C

↑

master

###Completely Removing the last Commit

Suppose C was your last commit and you want to go back to B, removing any work that you done on the way from B to C.

The command for that is:

git reset --hard HEAD~1

The result is:

A-B

↑

master

###Keeping the work of the last Commit Now if you want just remove the commit but keep all the work you had done till that commit then starting from:

(F)

A-B-C

↑

master

You need to run:

git reset HEAD~1

This will result in the following:

(F)

A-B-C

↑

master

In both cases HEAD is pointer to the last commit and reset tells git to move it back one place. If you dont use --hard, your files will remain as they were and running a git status will show you all your changes preserved but the commit will be lost.

##Merge Conflicts

###Why do they occur? When working on a shared project, you and your fellow collaborators are bound to make changes to the same file unkowing to each other and one of you might push his/her changes to the original repository while the other is in middle of his/her changes. Now when the latter person will try to fetch the new code into his/her local repository, git won't know who's changes to keep as a given file has been modified by both.

A typical merge conflict message looks like this:

$ git checkout style

Switched to branch 'style'

$ git merge master

Auto-merging lib/hello.py

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in lib/hello.py

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

Now your hello.py has merge conflicts as it was modified by you and someone else working on the project.

###Removing Merge Conflicts There are two cases where merge conflicts occur

- A file is modified by both users

- A file is modified by one or the other user while deleted by the other

##Disclaimer: This guide is aimed particularly at people starting open source contribution for the first time and aims to familiarise them with required patterns and expected contribution behaviour.