Takes a snapshot of the entire db and searches in the snapshot. This means that 2 selects in same transaction have their own snapshot and can see different data.

It is worth noting that UPDATEs and DELETEs get a row-level write lock (continue reading to find out what this means or see solution #S1.b)

When a transaction reads the same row twice but finds different data, because of some other transaction.

Consider the following example:

- Fetch row from db and read value (e.g. value == 1)

- Increment a field (server side) (value++ -> value == 2)

- Save back to db (SET value = 2)

If the above example is run concurrently from 2 apps, then the final value will be 2, not 3.

The same transaction may see different number of rows in the same table because of INSERTs of other transactions.

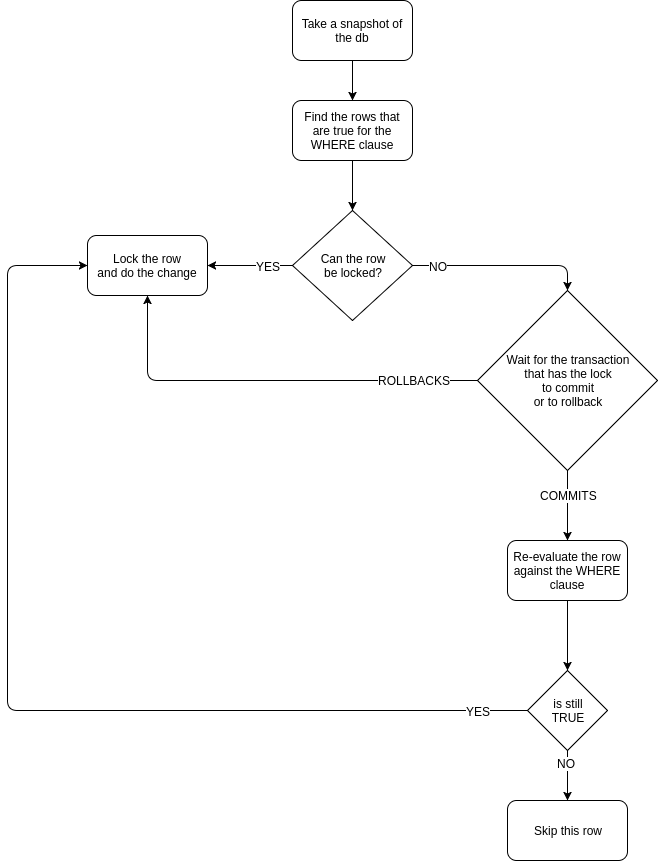

Due to how UPDATEs and DELETEs work, a row can be true for the WHERE clause and still not be updated. Consider the following example:

DB tables->

[name:ints]

n

---

1 -> row#1

2 -> row#2

T1: BEGIN

T1: UPDATE ints SET n = n+1;

T2: BEGIN

T2: DELETE from ints WHERE n = 2; -> blocks since delete is trying to modify rows being updated

T1: COMMIT

T2: COMMIT

DB tables->

[name:ints]

n

---

2

3

No row is being deleted. Because:

- DELETE finds #row2 having the value '2'

- It waits for it to become unlocked

- Once unlocked, it re-evaluates the row, but now it has the value '3', and it's no longer true.

- DELETE skips the row

The catch is that row#1 is not re-evaluated after the first transaction commits. Consult the UPDATE / DELETE image if you can't wrap your head around this, and you'll realize that T2 blocks only on #row2.

This happens when it is not possible to serialize (= execute the one after the other) the 2 transactions and getting the results that each transaction had.

Example:

T0> BEGIN;

T0> SELECT count(*) FROM ints;

count

-------

0

(1 row)

T1> BEGIN;

T1> SELECT count(*) FROM ints;

count

-------

0

(1 ROW)

T1> INSERT INTO ints SELECT 1;

T1> COMMIT;

T0> INSERT INTO ints SELECT 1;

T0> COMMIT;

Both T0 and T1 see count = 0, but there is no way when run sequentially that they both saw count = 0, because they both insert rows. So, if T0 runs first, T1 should see count = 1 and vice versa.

Postgres does not complain (does not throw errors (in the default isolation level)), but it can still create problems in your app.

Solves #P1 (Non-repeatable reads) and #P2 (Lost update)

Solves #P1 (Non-repeatable reads)

Add FOR SHARE after the SELECT statement. This will acquire a read lock in the matched rows. These rows will not be able to be updated or deleted from another transaction until the lock is released. This ensures that these rows will have the same value for the duration of the transaction. Of course, the transaction itself (the current one, with the read lock) can update/delete these rows and the changes will be visible within the transaction.

Solves #P2 (Lost update)

Add FOR UPDATE after the SELECT statement. This will acquire a write lock in the matched rows. This blocks other transactions when they try to acquire either a read or a write lock on the same row.

Now the #P2 example is not longer an issue. Consider P1 and P2 being two apps trying to access and increment a value in the same row:

- P1.1 Fetch row from db and read value (e.g. value == 1) with

FOR UPDATE - P2.1 Fetch row from db and read value with

FOR UPDATE-> blocks, becauseFOR UPDATEtries to acquire a write lock, while a write lock is present - P1.2. Increment the field (server side) (value++ -> value == 2)

- P1.3. Save back to db (SET value = 2) and COMMIT

- P2.1. -> unblocks, because the write lock is released, reads value == 2

- P2.2. Increment the field (server side) (value++ -> value == 3)

- P2.3. Save back to db (SET value = 3) and COMMIT

Now the value will have the expected value of 3

Note: You can use SKIP LOCKED in order to add a virtual WHERE locked = false and skip the locked rows from being selected and you being blocked, if you don't want that.

Can solve all the problems. Generally, while the isolation levels can solve #P1 and #P2, they do so in a less elegant way (aborting transactions), so #P1 and #P2 should best be solved with row-level locks (#S1) and not with different isolation levels.

There are 3 different isolation levels:

- Read committed (This is the default)

- Repeatable read

- Serializable

To see the current isolation level:

SHOW default_transaction_isolation;

To set a different level:

SET default_transaction_isolation='serializable';

Note: The isolation level is different per connected client basis.

Solves #P1, #P2, #P3 and #P4 (all apart from serialization anomaly)

When the transaction starts, it takes a snapshot of the database. All the following queries within the transaction will use this snapshot to do their changes.

What does this mean for the queries?

- SELECT: It "sees" only what is in the snapshot and nothing more. The select does not see any changes of every other transaction that commits after this transaction has begun.

- UPDATE / DELETE: If they stumble upon a locked row, they wait for it to be commited / rolled back. If the row gets commited by the other transaction, the snapshot is considered to be "out of date" and the current transaction aborts. If the row gets rolled back by the other transaction, then the query continues as if nothing has happened.

This means that when someone uses 'Repeatable read', their code has to be prepared to retry transactions if any of them fail.

#P3 (Phantom read) is solved because the rows that the transaction sees are from the snapshot in the beginning of the transaction, so no more/less rows can be read due to other transactions.

#P4 (Skipped modification) is solved by aborting all the transactions that wait for write lock in a row that is finally commited ("out of date" row).

Can solve all the problems.

This isolation level behaves exactly like 'Repeatable read', but it can also detect when two transactions cannot serialize correctly, and it will abort one of them to prevent a serialization anomaly. This comes with an overhead cost because Postgres now has an extra job - to detect the serialization anomalies.

This means that when someone uses 'Serializable', their code has to be prepared to retry transactions if any of them fail.

- Solve #P1 - Non-repeatable reads -> use #S1.a, row level read lock (

FOR SHARE) - Solve #P2 - Lost update -> use #S1.b, row level write lock (

FOR UPDATE) - Solve #P3 - Phantom read and #P4 - Skipped modification -> use #S2.a, 'Repeatable read' isolation level (RETRY TRANSACTION ON FAIL)

- Solve #P5 - Serialization anomaly -> use #S2.b, 'Serializable' isolation level (RETRY TRANSACTION ON FAIL)

Sources and full credit to: