This repository was born out questioning which would be faster:

let locked = some_async_mutex.lock().await;or

let locked = if let Ok(locked) = some_async_mutex.try_lock() {

locked

} else {

some_async_mutex.lock().await

};These results do not test every situation that locks can find themselves in. Always benchmark your own code rather than relying solelyh on third party benchmarks.

async-lockwins in these benchmarks in all categories. However, this is almost certainly due to a difference in fairness aglorithms between the different implementations.

tl;dr: It's, in-general, faster to try_lock() first.

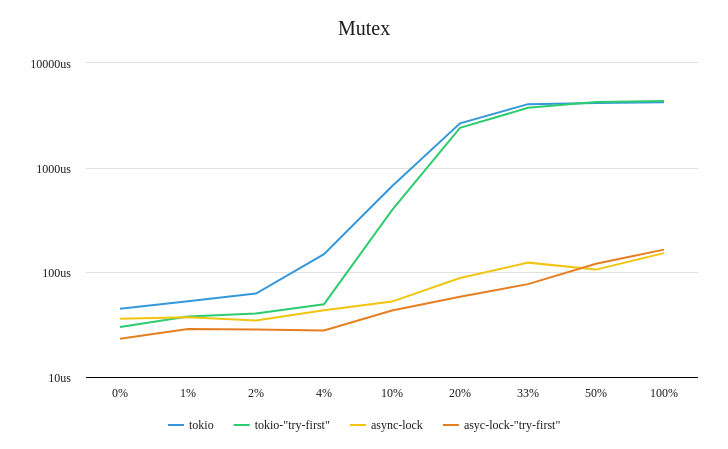

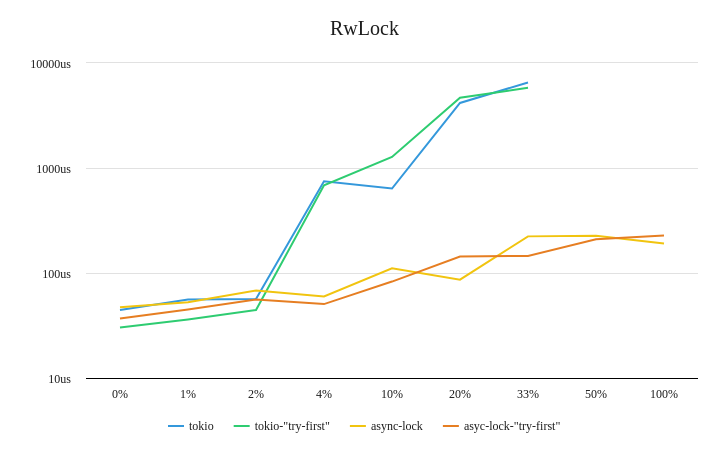

Here's two summary graphs that try to show the relative differences:

Note: the vertical axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale. This choice was made to make the relative differences at each datapoint more visible. Full Criterion report available here.

What's interesting to note is that at almost every measured datapoint, the "try-first" approach beats just calling the async locking function first. And, even when it doesn't, the difference is negligable.

Each of the benchmarks that simulate contention spawn a background async task that cycles through a list of locks locking them one by one in an infinite loop. The criterion benchmark function repeatedly acquires the first lock in the list.

For a 50% contention simulation, the background task cycles through 2 locks. For a 1% contention simulation, the background task cycles through 100 locks.

In BonsaiDb's server implementation, there is a structure ConnectedClient that stores the active connection state for each remote client. Internally, it granularly locks several pieces of data using async-aware locks.

These locks are generally acquired for very short periods of time, but they technically can have contention -- clients can have more than one request processed in parallel. However, in all practical purposes, they are very low-contention locks given how short the locks are held.

Many people suggest switching to parking_lot or std::sync for the highest performance, but those lock types do not play well with async executors. If you have any contention on those locks, they will pause the thread, blocking all other async tasks pending on that thread.

When developing Nebari, I started it as an async-native implementation, but I noticed that the overhead of an async function was noticable in benchmarks when compared to the same code written as a macro and inlined. This was despite all attempts to get the function to inline automatically with optimizations.

With that memory in mind, I hypothesized that calling the non-async function try_lock() and then falling back on lock().await could potentially be faster in low-contention situations. I did not expect to find that it is almost always faster in all situations.

The benchmarks were run on a machine running Manjaro Linux 5.12.19-1 with a AMD Ryzen 7 3800X on Rust version 1.56.1.