A simple framework for shell configuration management.

Features • Concepts • Installation • Usage

- Introduction

- Features

- Dependencies

- Supported shells

- Design & Concepts

- Installation

- Usage

- Updating

- Repositories using xsh

- References & Credits

The primary goal of xsh is to provide a uniform, consistent and modular structure for organizing shell configuration.

Each type of shell comes with its own set of startup files and initialization rules. Xsh abstracts away the complexity, allowing users to focus on configuration by avoiding the most common traps and pitfalls. Its modular configuration interface also encourages users to keep their configuration structured, maintainable and readable.

This project might be of interest to you if:

- You are frustrated by the

complexity and inconsistency

of

bashstartup rules, or you simply noticed that it doesn't behave as you would expect in some cases. - You like to keep your configuration structured, or would like to improve the readability and maintainability of your current configuration.

- You maintain configuration for multiple shells, and would like to keep a consistent structure while being able to reuse some parts.

- You want to quickly try out some shell plugin manager(s), or would like to decouple some of your custom configuration from your current plugin manager.

- Consistent startup/shutdown behavior for all supported shells.

- Self-contained configuration modules that can hook into

env,login,interactiveandlogoutruncoms for any supported shell. - Reusability of POSIX modules for other shells.

- Quickly bootstrap a configuration for a supported shell with

xsh bootstrap. - Quickly create new module runcoms with

xsh create. - Register modules from shell initialization files with

xsh module. - Load dependent modules from other modules with

xsh load. - List registered modules for the current shell with

xsh list. - Benchmark runcom/module loading times with

XSH_BENCHMARK.

See usage for examples and information about xsh commands.

- GNU

coreutils util-linux(forcolumn)sed- A POSIX-compatible shell that is supported.

On most Linux systems, these programs should already be installed.

For Unix systems using the BSD implementations of coreutils, so far only macOS

is supported and requires the installation of GNU coreutils:

brew install coreutilsThe coreutils prefixed with g will automatically be used if available.

Due to my refusal to forfeit the use of local, xsh is

not strictly POSIX-compatible. However most of the widely used shells derived

from the historical Bourne Shell are supported (which is what really matters):

ashdashbashand itsshemulationkshimplementations that supportlocalmkshzshand itsshandkshemulations

Feel free to open an issue if you'd like another shell to be supported.

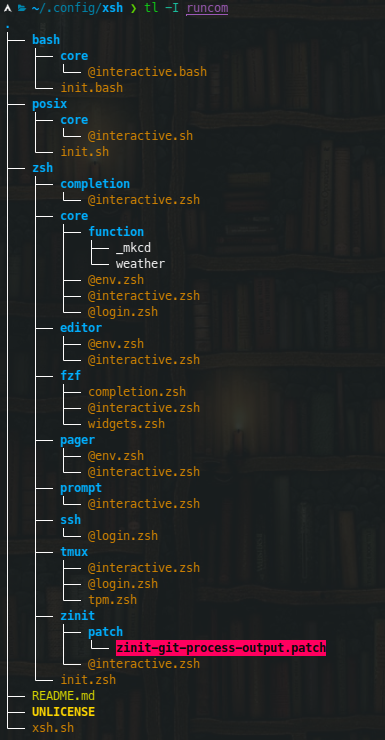

The design of xsh is built around three main concepts: shells, modules and runcoms.

Shells are the first class citizens of xsh. Configuration for specific shells

resides in a directory under $XSH_CONFIG_DIR matching that shell's name.

The default value of XSH_CONFIG_DIR is ~/.config/shell.

This document uses <shell> to refer to shell directories.

Each shell directory must contain an initialization file named init.<ext>.

If the initialization file for a shell isn't found when the shell starts up,

xsh will fallback to the initialization file for posix shells instead

(posix/init.sh). This special shell is precisely meant to be used as the

default fallback, but it is not required to bootstrap it if one doesn't need

that behavior.

Modules are simply pluggable pieces of configuration for a given shell.

Practically speaking, modules are directories in <shell>/.

Each module directory contains the runcoms that should be loaded by xsh,

as well as any additional files you would like to put there.

See the wikipedia page about runcoms.

Some disambiguation is needed here to avoid confusion between shell runcoms, xsh runcoms and module runcoms.

Shell runcoms are the shell-specific initialization files that are abstracted

away by xsh. When a shell starts or exits, it will load these files according

to its own set of rules, which xsh translates into a uniform and consistent

behavior for all shells. You normally don't need to worry about these, but for

reference the implementation for each shell can be found in the runcom

directory.

Xsh runcoms, or simply runcoms in the context of this document, are the resulting abstract concept. They can be seen as layers of configuration that are loaded by the shell in different contexts. There are conventionally 4 types of runcoms:

env: Always loaded regardless of how the shell is invoked.login: Loaded for login shells only.interactive: Loaded for interactive shells only.logout: Loaded for login shells on logout.

Module runcoms are the files loaded by xsh during shell initialization. They always belong to a module and should be written in the language of that module's shell. Each module should define at least one of the four runcoms.

To summarize, when a shell starts or exits, it loads its own specific shell runcoms. From the context of these files, xsh determines the abstract runcoms and attempts to load the corresponding module runcoms for each registered module.

Runcoms are always loaded in the following order:

- Shell startup:

env -> login -> interactive - Shell shutdown:

logout

This naturally means that all env module runcoms will run before all login

module runcoms, etc. Note that login-shells are not necessarily interactive,

and the reverse is also true. So during shell startup you can also have

env -> login and env -> interactive.

There is also the notable exception that the sh shell doesn't source any file

for non-login, non-interactive shells. This is the only case where the env

runcom won't be loaded.

To differentiate module runcoms from other files and to emphasize the special

role of these files in module directories, they must respect the following

naming scheme: [name]@<runcom>.<ext>.

For example, the file representing the login runcom for the core module of

the bash shell is bash/core/@login.bash.

Note that for the (somewhat special) posix shell, the extension is .sh and

not .posix

An optional name can be added to module runcoms, e.g. zsh/core/core@login.zsh.

Multiple files can also be defined for the same runcom, they will be loaded in the order defined by the current locale (alphabetically).

It is therefore possible to further split the configuration in multiple ordered files:

zsh/core/

01-opt@interactive.zsh

02-alias@interactive.zsh

...

You can change the special character for runcom files by setting the environment

variable XSH_RUNCOM_PREFIX (default @). Like XSH_DIR this should be set

before you user's login shell is started. Alternatively, it can be set on a

per-shell basis in the xsh initialization file

for that shell.

git clone https://github.com/sgleizes/xsh ~/.config/xshThe default location of the xsh repository is

${XDG_CONFIG_HOME:-$HOME/.config}/xsh. If you wish to use a different location,

the XSH_DIR environment variable must be set to that location before your

user's login shell is started, for instance in ~/.pam_environment.

The default location of your shell configuration is

${XDG_CONFIG_HOME:-$HOME/.config}/shell. If you want to store it at a

different location, you can set the XSH_CONFIG_DIR environment variable. This

must also be set before your user's login shell is started.

First, xsh must be made available in the current shell:

. "${XSH_DIR:-${XDG_CONFIG_HOME:-$HOME/.config}/xsh}/xsh.sh"Note that sourcing the script at this point will warn you that the initialization file for the current shell could not be found:

xsh: init: no configuration found for 'zsh'

This is expected and can be safely ignored since we haven't bootstrapped any

shell yet. You can now use the xsh function to bootstrap the current shell:

xsh bootstrapOr, to bootstrap multiple shells at once:

xsh bootstrap --shells posix:bash:zshIf you already have any of the shell runcoms in your $HOME, the bootstrap

command will automatically back them up so that the links to xsh runcoms can be

created.

The bootstrap command also creates a default initialization file and a core

module for the target shell(s).

Your existing configuration should have been automatically backed-up during the bootstrap operation. For simple cases it can be quickly migrated into the default module by using commands from the following snippet:

XSH_CONFIG_DIR="${XSH_CONFIG_DIR:-${XDG_CONFIG_HOME:-$HOME/.config}/shell}"

# For POSIX shells

cp "$HOME/.profile.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/posix/core/@login.sh"

cp "$HOME/.shrc.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/posix/core/@interactive.sh"

# For bash

cp "$HOME/.bash_profile.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/bash/core/@login.bash"

cp "$HOME/.bashrc.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/bash/core/@interactive.bash"

cp "$HOME/.bash_logout.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/bash/core/@logout.bash"

# For zsh

cp "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshenv.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/zsh/core/@env.zsh"

cp "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogin.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/zsh/core/@login.zsh"

cp "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshrc.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/zsh/core/@interactive.zsh"

cp "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogout.~1~" "$XSH_CONFIG_DIR/zsh/core/@logout.zsh"Note that this might not be exactly equivalent to your original setup, as the subtle differences between the original runcoms are now abstracted away. This is only meant as a quick way to start.

If you use one of the popular

zsh frameworks and plugin managers,

they can certainly be integrated in xsh. Some demonstration modules are

available in the xsh-modules

repository to quickly integrate with oh-my-zsh, prezto, zinit...

You can check that xsh is working properly by invoking your favorite shell with

XSH_VERBOSE=1:

XSH_VERBOSE=1 zshThis will print every unit that xsh sources during the shell startup process. You should at the very least see the xsh initialization file for the target shell be loaded. If an error occurs, it probably means that your shell is not supported.

Otherwise, everything should be ready for you to start playing around with your modules. See below for the next steps.

If you want to go back to your previous setup at any point, simply overwrite the

links created by xsh in your $HOME or ZDOTDIR by your original, backed-up

config:

# For POSIX shells

mv "$HOME/.profile.~1~" "$HOME/.profile"

mv "$HOME/.shrc.~1~" "$HOME/.shrc"

# For bash

mv "$HOME/.bash_profile.~1~" "$HOME/.bash_profile"

mv "$HOME/.bashrc.~1~" "$HOME/.bashrc"

mv "$HOME/.bash_logout.~1~" "$HOME/.bash_logout"

# For zsh

mv "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshenv.~1~" "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshenv"

mv "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogin.~1~" "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogin"

mv "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshrc.~1~" "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zshrc"

mv "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogout.~1~" "${ZDOTDIR:-$HOME}/.zlogout"If the backup doesn't exist for any file above, you can safely delete the link created by xsh for that file.

Assuming xsh bootstrap was run (see Installation), the

xsh source file will be read and executed whenever your shell starts,

at which point two things happen:

-

The shell function

xshis sourced. All xsh commands are available through this function.Documentation about available commands and options can be shown by invoking

xshwith no arguments. Usexsh help <command>to get more detailed information about a specific command. -

The command

xsh initis executed. This will source the initialization file for the current shell. See below.

Each type of shell must have a dedicated xsh initialization file located at

<shell>/init.<ext>. This file is automatically created by xsh bootstrap.

Its role is to register the modules to be loaded for each runcom: env,

login, interactive and logout.

The order in which the modules are registered defines the order in which

they will be loaded.

Modules can be registered using the xsh module command. Note that registering

a module doesn't directly execute that module's runcoms.

The default and most minimal xsh initialization file registers a single module:

xsh module coreThis will simply register the core module for all runcoms of the current

shell. For example, when xsh loads the env runcom, it will look for the

corresponding runcom file <shell>/core/@env.<ext>.

You can also register a module from another shell, if that other shell's language can be properly interpreted by the executing shell (e.g. loading a zsh module from a posix shell is not a good idea). For example:

File:

bash/init.bash

xsh module core -s posixThis will look for the runcoms of the core module in posix/core instead of

bash/core.

Additionally, in the following situation:

posix/core/

@env.sh

@interactive.sh

bash/core/

@login.bash

One might want to load the module runcoms from the posix shell if they don't exist in the current shell's module. The following achieves that behavior:

File:

bash/init.bash

xsh module core -s bash:posixNote that if a module runcom doesn't exist for a registered module, xsh will ignore it silently. If you like, you can explicitly specify which runcoms should be loaded when registering a module:

File:

bash/init.bash

xsh module core interactive:env:loginThis has the benefit of making the initialization file explicit about which

modules contribute to each runcom. This also affects xsh list and avoids

performing unnecessary file lookup every time a shell starts up.

See also xsh help and xsh help module.

A default core module with an interactive runcom file is automatically

created by xsh bootstrap. You can quickly create new module runcoms using the

xsh create command.

This command works similarly to the xsh module command:

xsh create ssh login:interactiveThis will create a new ssh module for the current shell, containing two runcom

files @login.<ext> and @interactive.<ext>. You can also use this command to

add a runcom to an existing module.

Note that the potentially new module needs to be registered in the initialization file for it to be automatically loaded.

See also xsh help and xsh help create.

The module contents and organization is entirely up to you. During this design process, you might find a need to express dependencies between modules, or to have a module runcom conditionally loaded by another module.

You can achieve this by using the xsh load command.

For example, in the following situation:

posix/core/

@env.sh

@interactive.sh

bash/core/

@interactive.bash

Even if you register the core module using xsh module core -s bash:posix,

the interactive runcom of the posix module would not be loaded, as it is found

in the bash module directory first.

You can load that runcom from the bash module as a dependency:

File:

bash/core/@interactive.bash

xsh load core -s posixThis will load posix/core/@interactive.sh directly.

That command can also be used to load a runcom of a different module as part of a module's configuration. This is usually needed if loading the dependee module is conditionally based on a predicate from the dependent module:

File:

bash/core/@interactive.bash

if some_predicate; then

xsh load other

fiThis will load bash/other/@interactive.bash directly.

See also xsh help and xsh help load.

The list of modules registered in the current shell can be displayed:

xsh listYou can also see which modules are loaded by xsh and in which order:

XSH_VERBOSE=1 zshXsh can also benchmark the loading time for each runcom:

XSH_BENCHMARK=1 zshCombining both options will show the loading time for each module runcom:

XSH_VERBOSE=1 XSH_BENCHMARK=1 zshNote that benchmarking for all shells other than zsh adds a significant

overhead (see benchmarking limitations), and so does not

accurately reflect the real loading time of your entire configuration.

It can still be useful to compare the loading times between different runcoms

and modules though.

It can be troublesome at first to figure out in which runcom a particular piece of configuration should reside. The Zsh documentation is a good place to start, along with this section of the Zsh FAQ.

-

The

envruncom should be kept as minimal as possible, as it defines the environment for non-login, non-interactive shells. It directly affects the execution of scripts and should never produce any output. It can for example set common environment variables likeEDITOR,PAGER, etc. -

The

loginruncom runs when your user's session starts, it defines the environment that will be inherited by all processes from that session. It can also be used to perform specific tasks at login-time, or to avoid performing a particular task every time you start an interactive shell. It is a good place to alter yourPATH, start anssh-agent, set theumask, etc. -

The

interactiveruncom is for everything else, this is where most of your configuration should reside. -

The

logoutruncom runs when your login shell is about to exit. You can use it to display a friendly goodbye message, or to cleanup old files from the trash, etc.

I have personally gone for that approach where I have a common set of

"essential" interactive settings (mostly aliases) defined for the posix shell,

that are loaded from other shells using xsh load.

This is so that I don't feel lost or frustrated whenever I need to use another shell. I also use it as a way to clearly distinguish basic, generic shell configuration from the more advanced, shell-specific configuration. It allows basic configuration to be factorized in a single place while being effective for all shells.

Naturally it implies that these common settings are written in a posixly correct manner. Some people might find that it adds clutter and complexity for little benefit.

You can specify the location of your shell configuration using the

XSH_CONFIG_DIR environment variable. Note that this must be set before your

user's login shell is started (e.g. in ~/.pam_environment).

If you prefer to have it all in one place, you can store shell configuration in the same directory than the xsh repository (in fact this used to be the default).

However, if you use git to version your shell configuration, keeping it inside

the xsh repository would be problematic.

Setting it to $HOME/.config or $HOME/.config/shell (the default) will result

in a

XDG-compliant

structure, with the configuration for each shell residing in ~/.config/<shell>

or ~/.config/shell/<shell>.

There is no strict requirement that the runcoms be env, login, interactive

and logout. These are simply the runcoms that are hooked to shell

initialization, but it is possible to add other "layers" of configuration that

are hooked to other things.

For this to work as expected, the modules must be registered with the custom runcom explicitly in the init file. They can then be loaded using:

xsh runcom my-custom-runcomOr, to load that runcom for a specific module only:

xsh load core my-custom-runcomImagination is the only limit here, but here are a few use cases I have thought of:

- Custom configuration hooks for users of a system, provided by system administrators.

- Specific commands or scripts related to a module, e.g.

xsh load pacman installto install CLI dependencies usingpacman. - Loading plugins of a specific shell plugin manager (

xsh runcomcan be called from the @interactive runcom of any module).

- Command arguments containing spaces, tabs or newlines are split in separate arguments.

- The module names must not contain spaces,

:or;characters.

The use of local is not strictly POSIX-compatible. However, it is widely

supported even by the most primitive POSIX-compliant shells (dash, ash and

some ksh implementations). Since xsh will probably be of little interest to

the people using shells even more primitive than this, support for these shells

will probably never be added.

See this post.

It should be noted that there are differences between the implementations,

e.g. local variables in dash and ash inherit their value in the parent scope

by default. To enforce truly distinct variables the form local var= is used to

preserve compatibility with these shells.

Benchmarking uses the date +%N command (except for zsh), which is not

supported by all implementations of date and also incurs a significant

performance impact due to the outer process and command substitution, which

is a shame when it comes to benchmarking...

Unfortunately, the invocation of bash runcoms is dependent on patches added by OS distributors and compile-time options. The implementation for the runcoms of each shell has not been tested on a variety of OS distributions so far, so please open an issue if you find that xsh is not behaving like it should on your distribution.

This project is still in early development stage, depending on the received feedback I might introduce breaking changes. Please make sure to check the release notes before upgrading.

Updating to the latest version only requires to git pull from the xsh

directory. Use git checkout <tag> to use a specific version.

The xsh-modules repository provides examples of integration with the most popular plugin managers.

My personal dotfiles repository also includes an extensive xsh-powered configuration that could help illustrating the benefits of a modular configuration.

If you decide to migrate your dotfiles to xsh, please add the xsh tag to your

repository so that we can all see the results of your hard work and be inspired

from it!

- The inspiration for creating this thing originated from this blog post.

- A little bit of shell history.

- The POSIX shell specification.