- Data Types and Operators

- Data Structures

- Control Flow

- Scripting

- Object - Oriented Programming

- Iterators and Generators

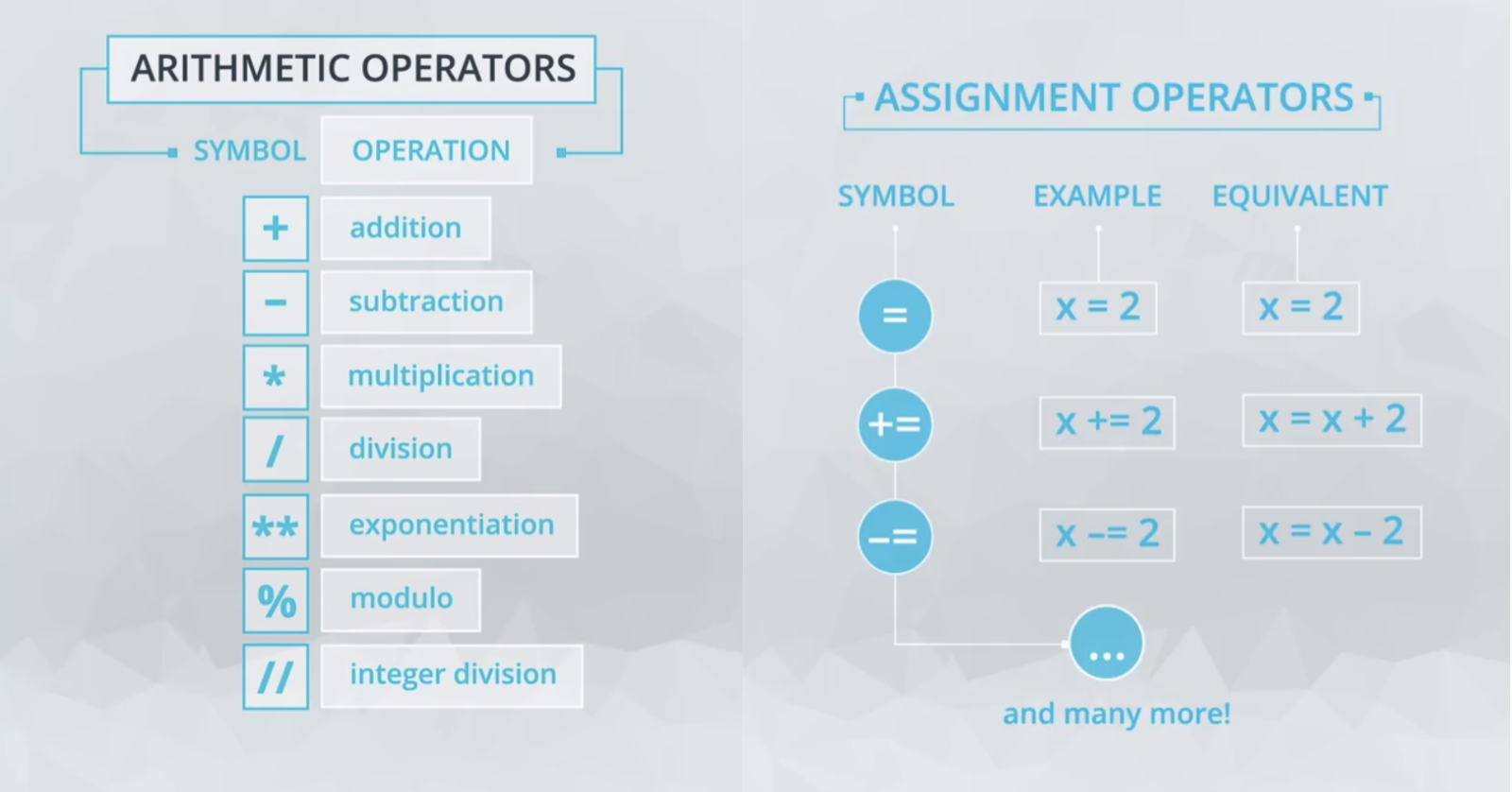

- Addition: +

- Subtraction: -

- Multiplication: *

- Division: /

- Mod (the remainder after dividing): %

- Exponentiation: **

- Divides and rounds down to the nearest integer: //

print(3 + 5) # 8

print(1 + 2 + 3 * 3) # 12

print(3 ** 2) # 9

print(9 % 2) # 1In any case, whatever term is on the left side, is now a name for whatever value is on the right side. Once a value has been assigned to a variable name, you can access the value from the variable name.

The following two are equivalent in terms of assignment:

x = 3

y = 4

z = 5and:

x, y, z = 3, 4, 5However, the above isn't a great way to assign variables in most cases, because our variable names should be descriptive of the values they hold.

Besides writing variable names that are descriptive, there are a few things to watch out for when naming variables in Python.

-

Only use ordinary letters, numbers and underscores in your variable names. They can’t have spaces, and need to start with a letter or underscore.

-

You can’t use Python's reserved words, or "keywords," as variable names. There are reserved words in every programming language that have important purposes, and you’ll learn about some of these throughout this course. Creating names that are descriptive of the values often will help you avoid using any of these keywords.

-

The pythonic way to name variables is to use all lowercase letters and underscores to separate words

There are two Python data types that could be used for numeric values:

int - for integer values float - for decimal or floating point values You can create a value that follows the data type by using the following syntax:

x = int(4.7) # x is now an integer 4

y = float(4) # y is now a float of 4.0You can check the type by using the type function:

>>> print(type(x))

int

>>> print(type(y))

floatBecause the float, or approximation, for 0.1 is actually slightly more than 0.1, when we add several of them together we can see the difference between the mathematically correct answer and the one that Python creates.

>>> print(.1 + .1 + .1 == .3)

FalseThe bool data type holds one of the values True or False, which are often encoded as 1 or 0, respectively.

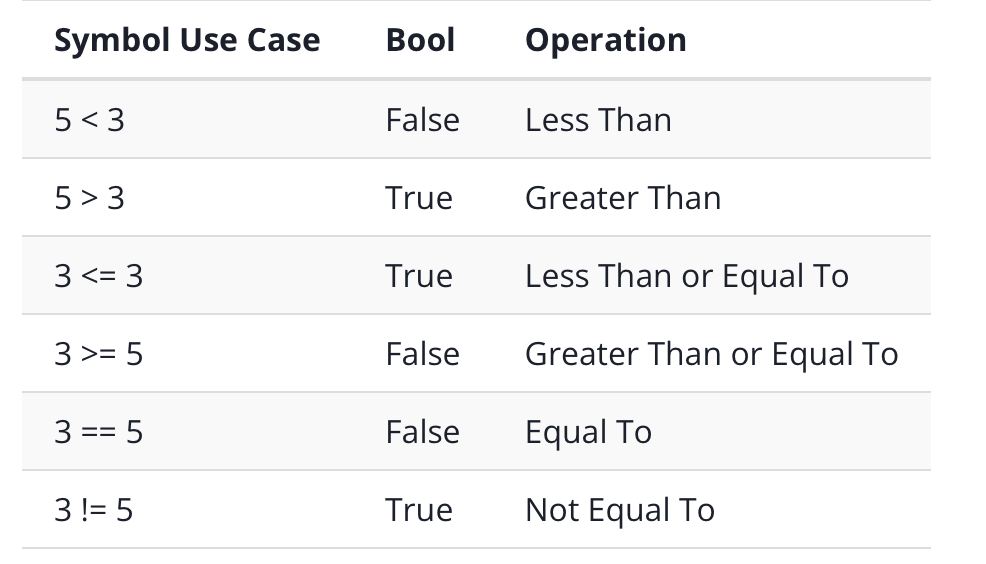

There are 6 comparison operators that are common to see in order to obtain a bool value:

Comparison Operators:

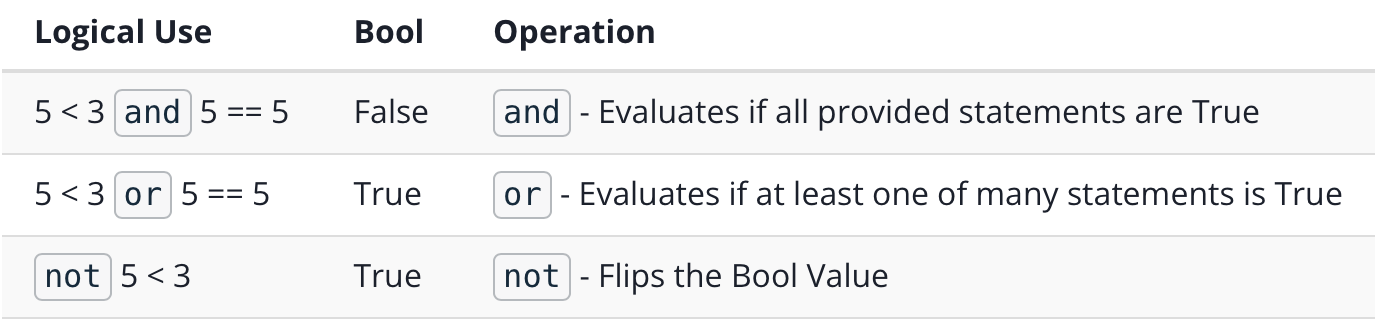

And there are three logical operators you need to be familiar with:

Strings in Python are shown as the variable type str. You can define a string with either double quotes " or single quotes '. If the string you are creating actually has one of these two values in it, then you need to be careful to assure your code doesn't give an error.

>>> my_string = 'this is a string!'

>>> my_string = "this is also a string!"You can also include a \ in your string to be able to include one of these quotes:

>>> this_string = 'Simon\'s skateboard is in the garage.'

>>> print(this_string) # Simon's skateboard is in the garage.If we don't use this, notice we get the following error:

>>> this_string = 'Simon's skateboard is in the garage.'

/*

File "<ipython-input-20-e80562c2a290>", line 1

this_string = 'Simon's skateboard is in the garage.'

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

*/There are a number of other operations you can use with strings as well.

>>> first_word = 'Hello'

>>> second_word = 'There'

>>> print(first_word + second_word)

HelloThere

>>> print(first_word + ' ' + second_word)

Hello There

>>> print(first_word * 5)

HelloHelloHelloHelloHello

>>> print(len(first_word))

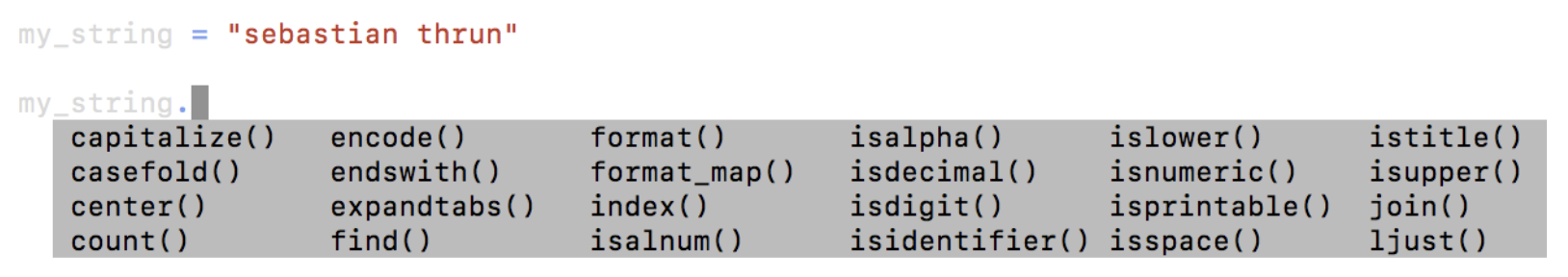

5A method in Python behaves similarly to a function. Methods actually are functions that are called using dot notation. For example, lower() is a string method that can be used like this, on a string called "sample string": sample_string.lower().

Methods are specific to the data type for a particular variable. So there are some built-in methods that are available for all strings, different methods that are available for all integers, etc.

len() is a built-in Python function that returns the length of an object, like a string. The length of a string is the number of characters in the string. This will always be an integer.

There is an example above, but here's another one:

print(len("ababa") / len("ab"))

2.5We will be using the format() string method a good bit in our future work in Python, and you will find it very valuable in your coding, especially with your print statements.

We can best illustrate how to use format() by looking at some examples.

print("Mohammed has {} balloons".format(27))

# output: Mohammed has 27 balloons

animal = "dog"

action = "bite"

print("Does your {} {}?".format(animal, action))

# output: Does your dog bite?

maria_string = "Maria loves {} and {}"

print(maria_string.format("math", "statistics"))

output: Maria loves math and statisticsA helpful string method when working with strings is the .split() method. This function or method returns a data container called a list that contains the words from the input string. We will be introducing you to the concept of lists in the next video.

The split method has two additional arguments (sep and maxsplit). The sep argument stands for "separator". It can be used to identify how the string should be split up (e.g., whitespace characters like space, tab, return, newline; specific punctuation (e.g., comma, dashes)). If the sep argument is not provided, the default separator is whitespace.

True to its name, the maxsplit argument provides the maximum number of splits. The argument gives maxsplit + 1 number of elements in the new list, with the remaining string being returned as the last element in the list.

You have seen four data types so far:

- int

- float

- bool

- string

The function type() can be used to check the data type of any variable you are working with. To convert a variable type to certian type: type_name(variable)

Everyone gets "bugs," or unexpected errors, in their code, and this is a normal and expected part of software development. We all say at one time or another, "Why isn't this computer doing what I want it to do?!"

So an important part of coding is "debugging" your code, to remove these bugs. This can often take a long time, and cause you frustration, but developing effective coding habits and mental calmness will help you address these issues. With determined persistence, you can prevail over these bugs!

Here are some tips on successful debugging that we'll discuss in more detail below:

Understand common error messages you might receive and what to do about them. Search for your error message, using the Web community. Use print statements.

Understanding Common Error Messages There are many different error messages that you can receive in Python, and learning how to interpret what they're telling you can be very helpful. Here are some common ones for starters:

- "ZeroDivisionError: division by zero." This is an error message that you saw earlier in this lesson. What did this error message indicate to us? You can look back in the Quiz: Arithmetic Operators section to review it if needed.

- "SyntaxError: unexpected EOF while parsing" This message is often produced when you have accidentally left out something, like a parenthesis. The message is saying it has unexpectedly reached the end of file ("EOF") and it still didn't find that right parenthesis. This can easily happen with code syntax involving pairs, like beginning and ending quotes also. Take a look at the two lines of code below. Executing these lines produces this syntax error message:

greeting = "hello"

print(greeting.upper- "TypeError: len() takes exactly one argument (0 given)" This kind of message could be given for many functions, like len in this case, if I accidentally do not include the required number of arguments when I'm calling a function, as below. This message tells me how many arguments the function requires (one in this case), compared with how many I gave it (0). I meant to use len(chars) to count the number of characters in this long word, but I forgot the argument.

chars = "supercalifragilisticexpialidocious"

len()Search for Your Error Message

Software developers like to share their problems and solutions with each other on the web, so using Google search, or searching in StackOverflow, or searching in Udacity's Knowledge forum are all good ways to get ideas on how to address a particular error message you're getting.

Copy and paste the error message into your web browser search tab, or in Knowledge, and see what others suggest about what might be causing it. You can copy and paste the whole error message, with or without quotes around it. Or you can search using just key words from the error message or situation you're facing, along with some other helpful words that describe your context, like Python and Mac.

Use Print Statements to Help Debugging

Adding print statements temporarily into your code can help you see which code lines have been executed before the error occurs, and see the values of any variables that might be important. This approach to debugging can also be helpful even if you're not receiving an error message, but things just aren't working the way you want.

We'll suggest particular occasions to use this approach in upcoming helpful places in this course.

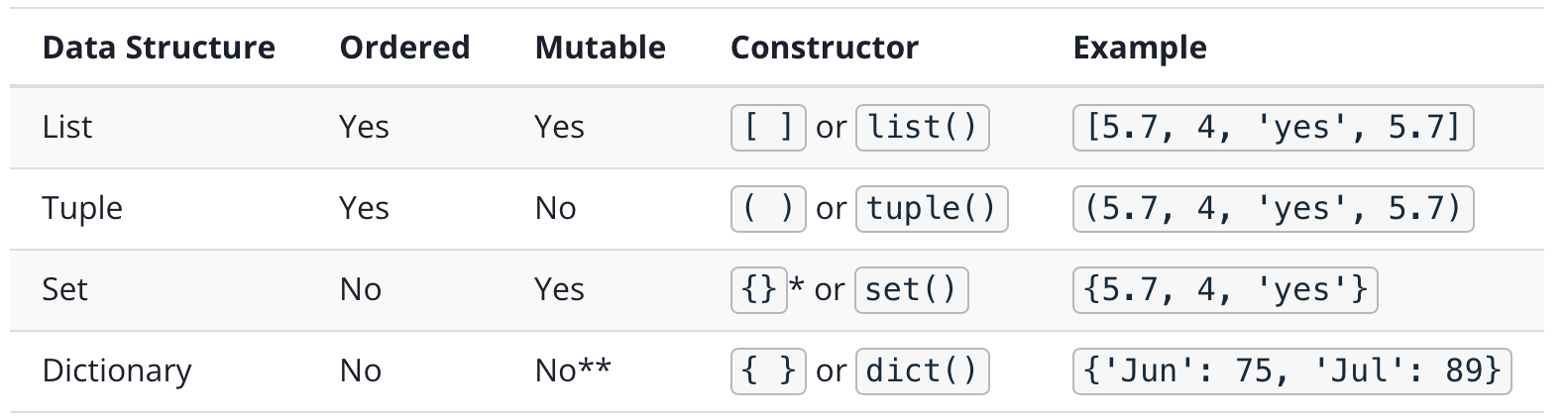

A list is one of the most common and basic data structures in Python. You saw here that you can create a list with square brackets. Lists can contain any mix and match of the data types you have seen so far.

list_of_random_things = [1, 3.4, 'a string', True]This is a list of 4 elements. All ordered containers (like lists) are indexed in python using a starting index of 0. Therefore, to pull the first value from the above list, we can write:

>>> list_of_random_things[0]

1Alternatively, you can index from the end of a list by using negative values, where -1 is the last element, -2 is the second to last element and so on.

>>> list_of_random_things[-1]

True

>>> list_of_random_things[-2]

a stringSlice and Dice with Lists

You saw that we can pull more than one value from a list at a time by using slicing. When using slicing, it is important to remember that the lower index is inclusive and the upper index is exclusive.

>>> list_of_random_things = [1, 3.4, 'a string', True]

>>> list_of_random_things[1:2]

[3.4]If you know that you want to start at the beginning, of the list you can also leave out this value.

>>> list_of_random_things[:2]

[1, 3.4]This type of indexing works exactly the same on strings, where the returned value will be a string.

>>> list_of_random_things[1:]

[3.4, 'a string', True]in and not in

We can also use in and not in to return a bool of whether an element exists within our list, or if one string is a substring of another.

>>> 'this' in 'this is a string'

True

>>> 'in' in 'this is a string'

True

>>> 'isa' in 'this is a string'

False

>>> 5 not in [1, 2, 3, 4, 6]

True

>>> 5 in [1, 2, 3, 4, 6]

FalseMutability and Order

Mutability is about whether or not we can change an object once it has been created. If an object (like a list or string) can be changed (like a list can), then it is called mutable. However, if an object cannot be changed with creating a completely new object (like strings), then the object is considered immutable.

>>> my_lst = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> my_lst[0] = 'one'

>>> print(my_lst)

['one', 2, 3, 4, 5]As shown above, you are able to replace 1 with 'one' in the above list. This is because lists are mutable. However, the following does not work:

>>> greeting = "Hello there"

>>> greeting[0] = 'M'This is because strings are immutable. This means to change this string, you will need to create a completely new string. There are two things to keep in mind for each of the data types you are using:

- Are they mutable?

- Are they ordered?

Order is about whether the position of an element in the object can be used to access the element. Both strings and lists are ordered. We can use the order to access parts of a list and string. However, you will see some data types in the next sections that will be unordered. For each of the upcoming data structures you see, it is useful to understand how you index, are they mutable, and are they ordered.

Useful Functions for Lists:

- len() returns how many elements are in a list.

- max() returns the greatest element of the list. How the greatest element is determined depends on what type objects are in the list. The maximum element in a list of numbers is the largest number. The maximum elements in a list of strings is element that would occur last if the list were sorted alphabetically. This works because the the max function is defined in terms of the greater than comparison operator. The max function is undefined for lists that contain elements from different, incomparable types.

- min() returns the smallest element in a list. min is the opposite of max, which returns the largest element in a list.

- sorted() returns a copy of a list in order from smallest to largest, leaving the list unchanged.

- join() is a string method that takes a list of strings as an argument, and returns a string consisting of the list elements joined by a separator string.

name = "-".join(["García", "O'Kelly"])

print(name)

# output: García-O'Kelly- append() A helpful method adds an element to the end of a list.

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd']

letters.append('z')

print(letters)

#output: ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'z']A tuple is another useful container. It's a data type for immutable ordered sequences of elements. They are often used to store related pieces of information. Consider this example involving latitude and longitude:

location = (13.4125, 103.866667)

print("Latitude:", location[0])

print("Longitude:", location[1])Tuples are similar to lists in that they store an ordered collection of objects which can be accessed by their indices. Unlike lists, however, tuples are immutable - you can't add and remove items from tuples, or sort them in place. Tuples can also be used to assign multiple variables in a compact way.

dimensions = 52, 40, 100

length, width, height = dimensions

print("The dimensions are {} x {} x {}".format(length, width, height))The parentheses are optional when defining tuples, and programmers frequently omit them if parentheses don't clarify the code. In the second line, three variables are assigned from the content of the tuple dimensions. This is called tuple unpacking. You can use tuple unpacking to assign the information from a tuple into multiple variables without having to access them one by one and make multiple assignment statements.

A set is a data type for mutable unordered collections of unique elements. One application of a set is to quickly remove duplicates from a list.

numbers = [1, 2, 6, 3, 1, 1, 6]

unique_nums = set(numbers)

print(unique_nums)

#output: {1, 2, 3, 6}Sets support the in operator the same as lists do. You can add elements to sets using the add method, and remove elements using the pop method, similar to lists. Although, when you pop an element from a set, a random element is removed. Remember that sets, unlike lists, are unordered so there is no "last element".

fruit = {"apple", "banana", "orange", "grapefruit"} # define a set

print("watermelon" in fruit) # check for element

fruit.add("watermelon") # add an element

print(fruit)

print(fruit.pop()) # remove a random element

print(fruit)

/* outputs:

False

{'grapefruit', 'orange', 'watermelon', 'banana', 'apple'}

grapefruit

{'orange', 'watermelon', 'banana', 'apple'} */A dictionary is a mutable data type that stores mappings of unique keys to values. Here's a dictionary that stores elements and their atomic numbers.

elements = {"hydrogen": 1, "helium": 2, "carbon": 6}Dictionaries can have keys of any immutable type, like integers or tuples, not just strings. It's not even necessary for every key to have the same type! We can look up values or insert new values in the dictionary using square brackets that enclose the key.

print(elements["helium"]) # print the value mapped to "helium"

elements["lithium"] = 3 # insert "lithium" with a value of 3 into the dictionaryWe can check whether a value is in a dictionary the same way we check whether a value is in a list or set with the in keyword. Dicts have a related method that's also useful, get. get looks up values in a dictionary, but unlike square brackets, get returns None (or a default value of your choice) if the key isn't found.

print("carbon" in elements) # True

print(elements.get("dilithium")) # NoneCarbon is in the dictionary, so True is printed. Dilithium isn’t in our dictionary so None is returned by get and then printed. If you expect lookups to sometimes fail, get might be a better tool than normal square bracket lookups because errors can crash your program.

Identity Operators

- is - evaluates if both sides have the same identity

- is not - evaluates if both sides have different identities

n = elements.get("dilithium")

print(n is None) # True

print(n is not None) # False- You can use curly braces to define a set like this: {1, 2, 3}. However, if you leave the curly braces empty like this: {} Python will instead create an empty dictionary. So to create an empty set, use set().

- A dictionary itself is mutable, but each of its individual keys must be immutable.

If Statement

An if statement is a conditional statement that runs or skips code based on whether a condition is true or false. Here's a simple example.

if phone_balance < 5:

phone_balance += 10

bank_balance -= 10If, Elif, Else

-

if: An if statement must always start with an if clause, which contains the first condition that is checked. If this evaluates to True, Python runs the code indented in this if block and then skips to the rest of the code after the if statement.

-

elif: elif is short for "else if." An elif clause is used to check for an additional condition if the conditions in the previous clauses in the if statement evaluate to False. As you can see in the example, you can have multiple elif blocks to handle different situations.

-

else: Last is the else clause, which must come at the end of an if statement if used. This clause doesn't require a condition. The code in an else block is run if all conditions above that in the if statement evaluate to False.

if season == 'spring':

print('plant the garden!')

elif season == 'summer':

print('water the garden!')

elif season == 'fall':

print('harvest the garden!')

elif season == 'winter':

print('stay indoors!')

else:

print('unrecognized season')Python has two kinds of loops - for loops and while loops. A for loop is used to "iterate", or do something repeatedly, over an iterable.

An iterable is an object that can return one of its elements at a time. This can include sequence types, such as strings, lists, and tuples, as well as non-sequence types, such as dictionaries and files.

cities = ['new york city', 'mountain view', 'chicago', 'los angeles']

for city in cities: #

print(city)

print("Done!")

/* output:

new york city

mountain view

chicago

los angeles

Done! */Components of a for Loop

- The first line of the loop starts with the for keyword, which signals that this is a for loop

- Following that is city in cities, indicating city is the iteration variable, and cities is the iterable being looped over. In the first iteration of the loop, city gets the value of the first element in cities, which is “new york city”.

- The for loop heading line always ends with a colon :

- Following the for loop heading is an indented block of code, the body of the loop, to be executed in each iteration of this loop. There is only one line in the body of this loop - print(city). 5.After the body of the loop has executed, we don't move on to the next line yet; we go back to the for heading line, where the iteration variable takes the value of the next element of the iterable. In the second iteration of the loop above, city takes the value of the next element in cities, which is "mountain view".

- This process repeats until the loop has iterated through all the elements of the iterable. Then, we move on to the line that follows the body of the loop - in this case, print("Done!"). We can tell what the next line after the body of the loop is because it is unindented.

Using the range() Function with for Loops

range() is a built-in function used to create an iterable sequence of numbers. You will frequently use range() with a for loop to repeat an action a certain number of times. Any variable can be used to iterate through the numbers, but Python programmers conventionally use i, as in this example:

for i in range(3):

print("Hello!")

/* output:

Hello!

Hello!

Hello! */range(start=0, stop, step=1) The range() function takes three integer arguments, the first and third of which are optional:

- The 'start' argument is the first number of the sequence. If unspecified, 'start' defaults to 0.

- The 'stop' argument is 1 more than the last number of the sequence. This argument must be specified.

- The 'step' argument is the difference between each number in the sequence. If unspecified, 'step' defaults to 1.

By now you are familiar with two important concepts:

- Counting with for loops

- The dictionary get method. These two can actually be combined to create a useful counter dictionary, something you will likely come across again. For example, we can create a dictionary, word_counter, that keeps track of the total count of each word in a string.

The following are a couple of ways to do it:

Method 1: Using a for loop to create a set of counters

Let's start with a list containing the words in a series of book titles:

book_title = ['great', 'expectations','the', 'adventures', 'of', 'sherlock','holmes','the','great','gasby','hamlet','adventures','of','huckleberry','fin']Step 1: Create an empty dictionary.

word_counter = {}Step 2: Iterate through each element in the list. If an element is already included in the dictionary, add 1 to its value. If not, add the element to the dictionary and set its value to 1.

for word in book_title:

if word not in word_counter:

word_counter[word] = 1

else:

word_counter[word] += 1What's happening here?

- The for loop iterates through each element in the list. For the first iteration, word takes the value 'great'.

- Next, the if statement checks if word is in the word_counter dictionary.

- Since it doesn't yet, the statement word_counter[word] = 1 adds great as a key to the dictionary with a value of 1.

- Then, it leaves the if else statement and moves on to the next iteration of the for loop. word now takes the value expectations and repeats the process.

- When the if condition is not met, it is because thatword already exists in the word_counter dictionary, and the statement word_counter[word] = word_counter[word] + 1 increases the count of that word by 1.

- Once the for loop finishes iterating through the list, the for loop is complete.

We can see the output by printing out the dictionary. Printing word_counter results in the following output.

{'great': 2, 'expectations': 1, 'the': 2, 'adventures': 2, 'of': 2, 'sherlock': 1, 'holmes': 1, 'gasby': 1, 'hamlet': 1, 'huckleberry': 1, 'fin': 1}Method 2: Using the get method

Step 1: Create an empty dictionary.

word_counter = {}Step 2: Iterate through each element, get() its value in the dictionary, and add 1. Recall that the dictionary get method is another way to retrieve the value of a key in a dictionary. Except unlike indexing, this will return a default value if the key is not found. If unspecified, this default value is set to None. We can use get with a default value of 0 to simplify the code from the first method above.

for word in book_title:

word_counter[word] = word_counter.get(word, 0) + 1What's happening here?

- The for loop iterates through the list as we saw earlier. The for loop feeds 'great' to the next statement in the body of the for loop.

- In this line: word_counter[word] = word_counter.get(word,0) + 1, since the key 'great' doesn't yet exist in the dictionary, get() will return the value 0 and word_counter[word] will be set to 1.

- Once it encounters a word that already exists in word_counter (e.g. the second appearance of 'the'), the value for that key is incremented by 1. On the second appearance of 'the', the key's value would add 1 again, resulting in 2.

- Once the for loop finishes iterating through the list, the for loop is complete.

ֿPrinting word_counter shows us we get the same result as we did in method 1.

{'great': 2, 'expectations': 1, 'the': 2, 'adventures': 2, 'of': 2, 'sherlock': 1, 'holmes': 1, 'gasby': 1, 'hamlet': 1, 'huckleberry': 1, 'fin': 1}When you iterate through a dictionary using a for loop, doing it the normal way (for n in some_dict) will only give you access to the keys in the dictionary - which is what you'd want in some situations. In other cases, you'd want to iterate through both the keys and values in the dictionary. Let's see how this is done in an example. Consider this dictionary that uses names of actors as keys and their characters as values.

cast = {

"Jerry Seinfeld": "Jerry Seinfeld",

"Julia Louis-Dreyfus": "Elaine Benes",

"Jason Alexander": "George Costanza",

"Michael Richards": "Cosmo Kramer"

}Iterating through it in the usual way with a for loop would give you just the keys, as shown below:

for key in cast:

print(key)

/* outputs:

Jerry Seinfeld

Julia Louis-Dreyfus

Jason Alexander

Michael Richards */If you wish to iterate through both keys and values, you can use the built-in method items like this:

for key, value in cast.items():

print("Actor: {} Role: {}".format(key, value))

/* outputs:

Actor: Jerry Seinfeld Role: Jerry Seinfeld

Actor: Julia Louis-Dreyfus Role: Elaine Benes

Actor: Jason Alexander Role: George Costanza

Actor: Michael Richards Role: Cosmo Krameritems is a method that returns tuples of key, value pairs, which you can use to iterate over dictionaries in for loops.

For loops are an example of "definite iteration" meaning that the loop's body is run a predefined number of times. This differs from "indefinite iteration" which is when a loop repeats an unknown number of times and ends when some condition is met, which is what happens in a while loop. Here's an example of a while loop.

card_deck = [4, 11, 8, 5, 13, 2, 8, 10]

hand = []

# adds the last element of the card_deck list to the hand list

# until the values in hand add up to 17 or more

while sum(hand) < 17:

hand.append(card_deck.pop())This example features two new functions. sum returns the sum of the elements in a list, and pop is a list method that removes the last element from a list and returns it.

Components of a While Loop

- The first line starts with the while keyword, indicating this is a while loop.

- Following that is a condition to be checked. In this example, that's sum(hand) <= 17.

- The while loop heading always ends with a colon :.

- Indented after this heading is the body of the while loop. If the condition for the while loop is true, the code lines in the loop's body will be executed.

- We then go back to the while heading line, and the condition is evaluated again. This process of checking the condition and then executing the loop repeats until the condition becomes false.

- When the condition becomes false, we move on to the line following the body of the loop, which will be unindented.

The indented body of the loop should modify at least one variable in the test condition. If the value of the test condition never changes, the result is an infinite loop.

Sometimes we need more control over when a loop should end, or skip an iteration. In these cases, we use the break and continue keywords, which can be used in both for and while loops.

- break terminates a loop

- continue skips one iteration of a loop

zip and enumerate are useful built-in functions that can come in handy when dealing with loops.

zip returns an iterator that combines multiple iterables into one sequence of tuples. Each tuple contains the elements in that position from all the iterables. For example, printing:

list(zip(['a', 'b', 'c'], [1, 2, 3])) would output [('a', 1), ('b', 2), ('c', 3)].

Like we did for range() we need to convert it to a list or iterate through it with a loop to see the elements. You could unpack each tuple in a for loop like this.

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c']

nums = [1, 2, 3]

for letter, num in zip(letters, nums):

print("{}: {}".format(letter, num))In addition to zipping two lists together, you can also unzip a list into tuples using an asterisk.

some_list = [('a', 1), ('b', 2), ('c', 3)]

letters, nums = zip(*some_list)This would create the same letters and nums tuples we saw earlier.

enumerate is a built in function that returns an iterator of tuples containing indices and values of a list. You'll often use this when you want the index along with each element of an iterable in a loop.

letters = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

for i, letter in enumerate(letters):

print(i, letter)

/* outputs:

0 a

1 b

2 c

3 d

4 e */In Python, you can create lists really quickly and concisely with list comprehensions. This example from earlier:

some_list = [('a', 1), ('b', 2), ('c', 3)]

letters, nums = zip(*some_list)can be reduced to:

capitalized_cities = [city.title() for city in cities]List comprehensions allow us to create a list using a for loop in one step.

You create a list comprehension with brackets [], including an expression to evaluate for each element in an iterable. This list comprehension above calls city.title() for each element city in cities, to create each element in the new list, capitalized_cities.

Conditionals in List Comprehensions

You can also add conditionals to list comprehensions (listcomps). After the iterable, you can use the if keyword to check a condition in each iteration.

squares = [x**2 for x in range(9) if x % 2 == 0] # = [0,4,16,36,64]If you would like to add else, you have to move the conditionals to the beginning of the listcomp, right after the expression, like this.

squares = [x**2 if x % 2 == 0 else x + 3 for x in range(9)]Function Header

Let's start with the function header, which is the first line of a function definition.

- The function header always starts with the def keyword, which indicates that this is a function definition.

- Then comes the function name (here, cylinder_volume), which follows the same naming conventions as variables. You can revisit the naming conventions below.

- Immediately after the name are parentheses that may include arguments separated by commas (here, height and radius). Arguments, or parameters, are values that are passed in as inputs when the function is called, and are used in the function body. If a function doesn't take arguments, these parentheses are left empty.

- The header always end with a colon :.

Function Body

The rest of the function is contained in the body, which is where the function does its work.

- The body of a function is the code indented after the header line. Here, it's the two lines that define pi and return the volume.

- Within this body, we can refer to the argument variables and define new variables, which can only be used within these indented lines.

- The body will often include a return statement, which is used to send back an output value from the function to the statement that called the function. A return statement consists of the return keyword followed by an expression that is evaluated to get the output value for the function. If there is no return statement, the function simply returns None.

Below, you'll find a code editor where you can experiment with this.

Naming Conventions for Functions Function names follow the same naming conventions as variables.

- Only use ordinary letters, numbers and underscores in your function names. They can’t have spaces, and need to start with a letter or underscore.

- You can’t use Python's reserved words or keywords for function names, as discussed earlier with variable names. Here again is that table of Python's reserved words.

- Try to use descriptive names that can help readers understand what the function does.

Default Arguments

We can add default arguments in a function to have default values for parameters that are unspecified in a function call.

def cylinder_volume(height, radius=5):

pi = 3.14159

return height * pi * radius ** 2In the example above, radius is set to 5 if that parameter is omitted in a function call. If we call cylinder_volume(10), the function will use 10 as the height and 5 as the radius. However, if we call cylinder_volume(10, 7) the 7 will simply overwrite the default value of 5.

Also notice here we are passing values to our arguments by position. It is possible to pass values in two ways - by position and by name. Each of these function calls are evaluated the same way.

cylinder_volume(10, 7) # pass in arguments by position

cylinder_volume(height=10, radius=7) # pass in arguments by nameVariable scope refers to which parts of a program a variable can be referenced, or used, from.

It's important to consider scope when using variables in functions. If a variable is created inside a function, it can only be used within that function. Accessing it outside that function is not possible.

# This will result in an error

def some_function():

word = "hello"

print(word)In the example above and the example below, word is said to have scope that is only local to each function. This means you can use the same name for different variables that are used in different functions.

# This works fine

def some_function():

word = "hello"

def another_function():

word = "goodbye"Variables defined outside functions, as in the example below, can still be accessed within a function. Here, word is said to have a global scope.

# This works fine

word = "hello"

def some_function():

print(word)

some_function()Notice that we can still access the value of the global variable word within this function. However, the value of a global variable can not be modified inside the function. If you want to modify that variable's value inside this function, it should be passed in as an argument. You'll see more on this in the next quiz.

Scope is essential to understanding how information is passed throughout programs in Python and really any programming language. Good practice: It is best to define variables in the smallest scope they will be needed in. While functions can refer to variables defined in a larger scope, this is very rarely a good idea since you may not know what variables you have defined if your program has a lot of variables.

You can use lambda expressions to create anonymous functions. That is, functions that don’t have a name. They are helpful for creating quick functions that aren’t needed later in your code. This can be especially useful for higher order functions, or functions that take in other functions as arguments.

With a lambda expression, this function:

def multiply(x, y):

return x * ycan be reduced to:

multiply = lambda x, y: x * yBoth of these functions are used in the same way. In either case, we can call multiply like this:

multiply(4, 7) # = 28Components of a Lambda Function

- The lambda keyword is used to indicate that this is a lambda expression.

- Following lambda are one or more arguments for the anonymous function separated by commas, followed by a colon :. Similar to functions, the way the arguments are named in a lambda expression is arbitrary.

- Last is an expression that is evaluated and returned in this function. This is a lot like an expression you might see as a return statement in a function.

With this structure, lambda expressions aren’t ideal for complex functions, but can be very useful for short, simple functions.

map() is a higher-order built-in function that takes a function and iterable as inputs, and returns an iterator that applies the function to each element of the iterable.

numbers = [

[34, 63, 88, 71, 29],

[90, 78, 51, 27, 45],

[63, 37, 85, 46, 22],

[51, 22, 34, 11, 18]

]

def mean(num_list):

return sum(num_list) / len(num_list)

averages = list(map(mean, numbers))

print(averages)

# with lambda

averages = list(map(lambda x: sum(x) / len(x), numbers))

print(averages) # output: [57.0, 58.2, 50.6, 27.2]filter() is a higher-order built-in function that takes a function and iterable as inputs and returns an iterator with the elements from the iterable for which the function returns True.

cities = ["New York City", "Los Angeles", "Chicago", "Mountain View", "Denver", "Boston"]

short_cities = list(filter(lambda x: len(x) < 10, cities))

print(short_cities) # output: ['Chicago', 'Denver', 'Boston']1, Open your terminal and use cd to navigate to the directory containing that script file. 2. Now that you’re in the directory with the file, you can run it by typing python first_script.py and pressing enter. Note: You may have to enter python3 instead of python to execute Python 3 if you have both versions installed on your computer.

We can get raw input from the user with the built-in function input, which takes in an optional string argument that you can use to specify a message to show to the user when asking for input.

name = input("Enter your name: ")

print("Hello there, {}!".format(name.title()))This prompts the user to enter a name and then uses the input in a greeting. The input function takes in whatever the user types and stores it as a string. If you want to interpret their input as something other than a string, like an integer, as in the example below, you need to wrap the result with the new type to convert it from a string.

num = int(input("Enter an integer"))

print("hello" * num)We can also interpret user input as a Python expression using the built-in function eval. This function evaluates a string as a line of Python.

num = int(input("Enter an integer"))

print("hello" * num)If the user inputs 2 * 3, this outputs 6.

- Syntax errors occur when Python can’t interpret our code, since we didn’t follow the correct syntax for Python. These are errors you’re likely to get when you make a typo, or you’re first starting to learn Python.

- Exceptions occur when unexpected things happen during execution of a program, even if the code is syntactically correct. There are different types of built-in exceptions in Python, and you can see which exception is thrown in the error message.

Try Statement

We can use try statements to handle exceptions. There are four clauses you can use (one more in addition to those shown in the video).

- try: This is the only mandatory clause in a try statement. The code in this block is the first thing that Python runs in a try statement.

- except: If Python runs into an exception while running the try block, it will jump to the except block that handles that exception.

- else: If Python runs into no exceptions while running the try block, it will run the code in this block after running the try block.

- finally: Before Python leaves this try statement, it will run the code in this finally block under any conditions, even if it's ending the program. E.g., if Python ran into an error while running code in the except or else block, this finally block will still be executed before stopping the program.

Specifying Exceptions

We can actually specify which error we want to handle in an except block like this:

try:

# some code

except ValueError:

# some code

# if we want this handler to address more than one type of exception,

# we can include a parenthesized tuple after the except with the exceptions.

try:

# some code

except (ValueError, KeyboardInterrupt):

# some code

# if we want to execute different blocks of code depending on the exception, you can have multiple except blocks.

try:

# some code

except ValueError:

# some code

except KeyboardInterrupt:

# some codeWhen you handle an exception, you can still access its error message like this:

try:

# some code

except ZeroDivisionError as e:

# some code

print("ZeroDivisionError occurred: {}".format(e))This would print something like this:

ZeroDivisionError occurred: integer division or modulo by zeroSo you can still access error messages, even if you handle them to keep your program from crashing! If you don't have a specific error you're handling, you can still access the message like this:

try:

# some code

except Exception as e:

# some code

print("Exception occurred: {}".format(e))Exception is just the base class for all built-in exceptions. You can learn more about Python's exceptions here.

Reading a File

f = open('my_path/my_file.txt', 'r')

file_data = f.read()

f.close()- First open the file using the built-in function, open. This requires a string that shows the path to the file. The open function returns a file object, which is a Python object through which Python interacts with the file itself. Here, we assign this object to the variable f.

- There are optional parameters you can specify in the open function. One is the mode in which we open the file. Here, we use r or read only. This is actually the default value for the mode argument.

- Use the read method to access the contents from the file object. This read method takes the text contained in a file and puts it into a string. Here, we assign the string returned from this method into the variable file_data.

- When finished with the file, use the close method to free up any system resources taken up by the file.

Writing to a File

f = open('my_path/my_file.txt', 'w')

f.write("Hello there!")

f.close()- Open the file in writing ('w') mode. If the file does not exist, Python will create it for you. If you open an existing file in writing mode, any content that it had contained previously will be deleted. If you're interested in adding to an existing file, without deleting its content, you should use the append ('a') mode instead of write.

- Use the write method to add text to the file.

- Close the file when finished.

With

Python provides a special syntax that auto-closes a file for you once you're finished using it.

with open('my_path/my_file.txt', 'r') as f:

file_data = f.read() # inside the scope

# outside the scope , file closed automatically but you don't lose the data

print(file_data) # works fine ,can use all string methods on file_data We can actually import Python code from other scripts, which is helpful if you are working on a bigger project where you want to organize your code into multiple files and reuse code in those files. If the Python script you want to import is in the same directory as your current script, you just type import followed by the name of the file, without the .py extension.

import useful_functionsIt's the standard convention for import statements to be written at the top of a Python script, each one on a separate line. This import statement creates a module object called useful_functions. Modules are just Python files that contain definitions and statements. To access objects from an imported module, you need to use dot notation.

import useful_functions

useful_functions.add_five([1, 2, 3, 4])We can add an alias to an imported module to reference it with a different name.

import useful_functions as uf

uf.add_five([1, 2, 3, 4])Using a main block

To avoid running executable statements in a script when it's imported as a module in another script, include these lines in an if name == "main" block. Or alternatively, include them in a function called main() and call this in the if main block.

Whenever we run a script like this, Python actually sets a special built-in variable called name for any module. When we run a script, Python recognizes this module as the main program, and sets the name variable for this module to the string "main". For any modules that are imported in this script, this built-in ** name** variable is just set to the name of that module. Therefore, the condition if name == "main"is just checking whether this module is the main program.

# useful_functions.py

def mean(num_list):

return sum(num_list) / len(num_list)

def add_five(num_list):

return [n + 5 for n in num_list]

def main():

print("Testing mean function")

n_list = [34, 44, 23, 46, 12, 24]

correct_mean = 30.5

assert(mean(n_list) == correct_mean)

print("Testing add_five function")

correct_list = [39, 49, 28, 51, 17, 29]

assert(add_five(n_list) == correct_list)

print("All tests passed!")

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()Techniques for Importing Modules

There are other variants of import statements that are useful in different situations.

- To import an individual function or class from a module:

from module_name import object_name- To import multiple individual objects from a module:

from module_name import first_object, second_object- To rename a module:

import module_name as new_name- To import an object from a module and rename it:

from module_name import object_name as new_name- To import every object individually from a module (DO NOT DO THIS):

from module_name import *- If you really want to use all of the objects from a module, use the standard import module_name statement instead and access each of the objects with the dot notation.

import module_nameModules, Packages, and Names

In order to manage the code better, modules in the Python Standard Library are split down into sub-modules that are contained within a package. A package is simply a module that contains sub-modules. A sub-module is specified with the usual dot notation.

Modules that are submodules are specified by the package name and then the submodule name separated by a dot. You can import the submodule like this.

import package_name.submodule_nameA class is a user-defined blueprint or prototype from which objects are created. Classes provide a means of bundling data and functionality together. Creating a new class creates a new type of object, allowing new instances of that type to be made. Each class instance can have attributes attached to it for maintaining its state. Class instances can also have methods (defined by their class) for modifying their state.

# class definition syntax:

class ClassName:

# Statement

# object definition syntax:

obj = ClassName()

print(obj.atrr)Class creates a user-defined data structure, which holds its own data members and member functions, which can be accessed and used by creating an instance of that class. A class is like a blueprint for an object.

Some points on Python class:

- Classes are created by keyword class.

- Attributes are the variables that belong to a class.

- Attributes are always public and can be accessed using the dot (.) operator. Eg.: Myclass.Myattribute

Class Objects

An Object is an instance of a Class. A class is like a blueprint while an instance is a copy of the class with actual values. It’s not an idea anymore, it’s an actual dog, like a dog of breed pug who’s seven years old. You can have many dogs to create many different instances, but without the class as a guide, you would be lost, not knowing what information is required. An object consists of :

- State: It is represented by the attributes of an object. It also reflects the properties of an object.

- Behavior: It is represented by the methods of an object. It also reflects the response of an object to other objects.

- Identity: It gives a unique name to an object and enables one object to interact with other objects.

class Dog:

# A simple class

# attribute

attr1 = "mammal"

attr2 = "dog"

# A sample method

def fun(self):

print("I'm a", self.attr1)

print("I'm a", self.attr2)

# Driver code

# Object instantiation

luka = Dog()

# Accessing class attributes

# and method through objects

print(luka.attr1)

luka.fun()self

- Class methods must have an extra first parameter in the method definition. We do not give a value for this parameter when we call the method, Python provides it.

- If we have a method that takes no arguments, then we still have to have one argument.

- This is similar to this pointer in C++ and this reference in Java.

When we call a method of this object as myobject.method(arg1, arg2), this is automatically converted by Python into MyClass.method(myobject, arg1, arg2) – this is all the special self is about.

init method

The init method is similar to constructors in C++ and Java. Constructors are used to initializing the object’s state. Like methods, a constructor also contains a collection of statements(i.e. instructions) that are executed at the time of Object creation. It runs as soon as an object of a class is instantiated. The method is useful to do any initialization you want to do with your object.

class Dog:

# Class Variable

animal = 'dog'

# The init method or constructor

def __init__(self, breed, color):

# Instance Variable

self.breed = breed

self.color = color

# A sample method

def fun(self):

print("I like to play:)

print("Let's go for a walk!")

# Objects of Dog class

Luka = Dog("Pug", "brown")

Buzo = Dog("Bulldog", "black")

print('Luka details:')

print('Luka is a', Rodger.animal)

print('Breed: ', Luka.breed)

print('Color: ', Luka.color)

print('\nBuzo details:')

print('Buzo is a', Buzo.animal)

print('Breed: ', Buzo.breed)

print('Color: ', Buzo.color)

Luka.fun()

# Class variables can be accessed using class

# name also

print("\nAccessing class variable using class name")

print(Dog.animal)Output:

Rodger details:

Rodger is a dog

Breed: Pug

Color: brown

Buzo details:

Buzo is a dog

Breed: Bulldog

Color: black

I like to play

Let's go for a walk!

Accessing class variable using class name

dogConstructors

Constructors are generally used for instantiating an object. The task of constructors is to initialize(assign values) to the data members of the class when an object of the class is created. In Python the init() method is called the constructor and is always called when an object is created. Syntax of constructor declaration :

# # parameterized constructor

def __init__(self, a, b):

# body of the constructorTypes of constructors :

- default constructor: The default constructor is a simple constructor which doesn’t accept any arguments. Its definition has only one argument which is a reference to the instance being constructed.

- parameterized constructor: constructor with parameters is known as parameterized constructor. The parameterized constructor takes its first argument as a reference to the instance being constructed known as self and the rest of the arguments are provided by the programmer.

Destructors

Destructors are called when an object gets destroyed. In Python, destructors are not needed as much as in C++ because Python has a garbage collector that handles **memory management automatically. ** The del() method is a known as a destructor method in Python. It is called when all references to the object have been deleted i.e when an object is garbage collected. Syntax of destructor declaration :

def __del__(self):

# body of destructorNote : A reference to objects is also deleted when the object goes out of reference or when the program ends.

Note : The destructor was called after the program ended or when all the references to object are deleted i.e when the reference count becomes zero, not when object went out of scope.

Therefore, if your instances are involved in circular references they will live in memory for as long as the application run.

Inheritance is the capability of one class to derive or inherit the properties from another class.

Benefits of inheritance are:

- It represents real-world relationships well.

- It provides the reusability of a code. We don’t have to write the same code again and again. Also, it allows us to add more features to a class without modifying it.

- It is transitive in nature, which means that if class B inherits from another class A, then all the subclasses of B would automatically inherit from class A.

Class BaseClass:

{Body}

Class DerivedClass(BaseClass):

{Body}class Person(object):

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# To get name

def getName(self):

return self.name

# To check if this person is an employee

def isEmployee(self):

return False

# Inherited or Subclass (Note Person in bracket)

class Employee(Person):

# Here we return true

def isEmployee(self):

return True

# Driver code

emp = Person("Geek1") # An Object of Person

print(emp.getName(), emp.isEmployee())

emp = Employee("Geek2") # An Object of Employee

print(emp.getName(), emp.isEmployee())

""" output

Geek1 False

Geek2 True """Subclassing (Calling constructor of parent class)

A child class needs to identify which class is its parent class. This can be done by mentioning the parent class name in the definition of the child class.

Eg: class subclass_name (superclass_name):

# parent class

class Person(object):

# __init__ is known as the constructor

def __init__(self, name, idnumber):

self.name = name

self.idnumber = idnumber

def display(self):

print(self.name)

print(self.idnumber)

# child class

class Employee(Person):

def __init__(self, name, idnumber, salary, post):

self.salary = salary

self.post = post

# invoking the __init__ of the parent class

Person.__init__(self, name, idnumber)

# creation of an object variable or an instance

a = Employee('Rahul', 886012, 200000, "Intern")

# calling a function of the class Person using its instance

a.display()

# output: Rahul 886012Different types of Inheritance:

-

Single inheritance: When a child class inherits from only one parent class, it is called single inheritance. We saw an example above.

-

Multiple inheritances: When a child class inherits from multiple parent classes, it is called multiple inheritances.

class Base1(object):

def __init__(self):

self.str1 = "Geek1"

print("Base1")

class Base2(object):

def __init__(self):

self.str2 = "Geek2"

print("Base2")

class Derived(Base1, Base2):

def __init__(self):

# Calling constructors of Base1

# and Base2 classes

Base1.__init__(self)

Base2.__init__(self)

print("Derived")

def printStrs(self):

print(self.str1, self.str2)

ob = Derived()

ob.printStrs()

""" output

Base1

Base2

Derived

Geek1 Geek2 """- Multilevel inheritance: When we have a child and grandchild relationship.

class Base(object):

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# To get name

def getName(self):

return self.name

# Inherited or Sub class (Note Person in bracket)

class Child(Base):

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name, age):

Base.__init__(self, name)

self.age = age

# To get name

def getAge(self):

return self.age

# Inherited or Sub class (Note Person in bracket)

class GrandChild(Child):

# Constructor

def __init__(self, name, age, address):

Child.__init__(self, name, age)

self.address = address

# To get address

def getAddress(self):

return self.address

# Driver code

g = GrandChild("Geek1", 23, "Noida")

print(g.getName(), g.getAge(), g.getAddress())

# output: Geek1 23 Noida- Hierarchical inheritance More than one derived class are created from a single base.

- Hybrid inheritance: This form combines more than one form of inheritance. Basically, it is a blend of more than one type of inheritance.

**Private members of the parent class **

We don’t always want the instance variables of the parent class to be inherited by the child class i.e. we can make some of the instance variables of the parent class private, which won’t be available to the child class. We can make an instance variable private by adding double underscores before its name. For example:

class C(object):

def __init__(self):

self.c = 21

# d is private instance variable

self.__d = 42

class D(C):

def __init__(self):

self.e = 84

C.__init__(self)

object1 = D()

# produces an error as d is private instance variable

print(object1.d)

""" output

File "/home/993bb61c3e76cda5bb67bd9ea05956a1.py", line 16, in

print (object1.d)

AttributeError: type object 'D' has no attribute 'd' """Since ‘d’ is made private by those underscores, it is not available to the child class ‘D’ and hence the error.

Encapsulation is one of the fundamental concepts in object-oriented programming (OOP). It describes the idea of wrapping data and the methods that work on data within one unit. This puts restrictions on accessing variables and methods directly and can prevent the accidental modification of data. To prevent accidental change, an object’s variable can only be changed by an object’s method. Those types of variables are known as private variables.

Protected members

Protected members (in C++ and JAVA) are those members of the class that cannot be accessed outside the class but can be accessed from within the class and its subclasses. To accomplish this in Python, just follow the convention by prefixing the name of the member by a single underscore “_”.

Although the protected variable can be accessed out of the class as well as in the derived class(modified too in derived class), it is customary(convention not a rule) to not access the protected out the class body.

Private members

Private members are similar to protected members, the difference is that the class members declared private should neither be accessed outside the class nor by any base class. In Python, there is no existence of Private instance variables that cannot be accessed except inside a class.

However, to define a private member prefix the member name with double underscore “__”.

In programming, polymorphism means the same function name (but different signatures) being used for different types.

# len() being used for a string

print(len("geeks"))

# len() being used for a list

print(len([10, 20, 30]))

# output: 3,5Polymorphism with class methods:

The below code shows how Python can use two different class types, in the same way. We create a for loop that iterates through a tuple of objects. Then call the methods without being concerned about which class type each object is. We assume that these methods actually exist in each class.

class India():

def capital(self):

print("New Delhi is the capital of India.")

def language(self):

print("Hindi is the most widely spoken language of India.")

def type(self):

print("India is a developing country.")

class USA():

def capital(self):

print("Washington, D.C. is the capital of USA.")

def language(self):

print("English is the primary language of USA.")

def type(self):

print("USA is a developed country.")

obj_ind = India()

obj_usa = USA()

for country in (obj_ind, obj_usa):

country.capital()

country.language()

country.type()

""" output

New Delhi is the capital of India.

Hindi is the most widely spoken language of India.

India is a developing country.

Washington, D.C. is the capital of USA.

English is the primary language of USA.

USA is a developed country. """**Polymorphism with Inheritance: **

In Python, Polymorphism lets us define methods in the child class that have the same name as the methods in the parent class. In inheritance, the child class inherits the methods from the parent class. However, it is possible to modify a method in a child class that it has inherited from the parent class. This is particularly useful in cases where the method inherited from the parent class doesn’t quite fit the child class. In such cases, we re-implement the method in the child class. This process of re-implementing a method in the child class is known as Method Overriding.

class Bird:

def intro(self):

print("There are many types of birds.")

def flight(self):

print("Most of the birds can fly but some cannot.")

class sparrow(Bird):

def flight(self):

print("Sparrows can fly.")

class ostrich(Bird):

def flight(self):

print("Ostriches cannot fly.")

obj_bird = Bird()

obj_spr = sparrow()

obj_ost = ostrich()

obj_bird.intro()

obj_bird.flight()

obj_spr.intro()

obj_spr.flight()

obj_ost.intro()

obj_ost.flight()

""" output

There are many types of birds.

Most of the birds can fly but some cannot.

There are many types of birds.

Sparrows can fly.

There are many types of birds.

Ostriches cannot fly. """Polymorphism with a Function and objects: It is also possible to create a function that can take any object, allowing for polymorphism. In this example, let’s create a function called “func()” which will take an object which we will name “obj”. Though we are using the name ‘obj’, any instantiated object will be able to be called into this function. Next, let’s give the function something to do that uses the ‘obj’ object we passed to it. In this case, let’s call the three methods, viz., capital(), language() and type(), each of which is defined in the two classes ‘India’ and ‘USA’. Next, let’s create instantiations of both the ‘India’ and ‘USA’ classes if we don’t have them already. With those, we can call their action using the same func() function:

def func(obj):

obj.capital()

obj.language()

obj.type()

obj_ind = India()

obj_usa = USA()

func(obj_ind)

func(obj_usa)All variables which are assigned a value in the class declaration are class variables. And variables that are assigned values inside methods are instance variables.

# Class for Computer Science Student

class CSStudent:

stream = 'cse' # Class Variable

def __init__(self,name,roll):

self.name = name # Instance Variable

self.roll = roll # Instance Variable

# Objects of CSStudent class

a = CSStudent('Geek', 1)

b = CSStudent('Nerd', 2)

print(a.stream) # prints "cse"

print(b.stream) # prints "cse"

print(a.name) # prints "Geek"

print(b.name) # prints "Nerd"

print(a.roll) # prints "1"

print(b.roll) # prints "2"

# Class variables can be accessed using class

# name also

print(CSStudent.stream) # prints "cse"

# Now if we change the stream for just a it won't be changed for b

a.stream = 'ece'

print(a.stream) # prints 'ece'

print(b.stream) # prints 'cse'

# To change the stream for all instances of the class we can change it

# directly from the class

CSStudent.stream = 'mech'

print(a.stream) # prints 'ece'

print(b.stream) # prints 'mech'

""" output

cse

cse

Geek

Nerd

1

2

cse

ece

cse

ece

mech """Class Method

The @classmethod decorator is a built-in function decorator that is an expression that gets evaluated after your function is defined. The result of that evaluation shadows your function definition. A class method receives the class as an implicit first argument, just like an instance method receives the instance

class C(object):

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

....

# fun: function that needs to be converted into a class method

# returns: a class method for function.- A class method is a method that is bound to the class and not the object of the class. They have the access to the state of the class as it takes a class parameter that points to the class and not the object instance.

- It can modify a class state that would apply across all the instances of the class. For example, it can modify a class variable that will be applicable to all the instances.

Static Method

A @staticmethod does not receive an implicit first argument. A static method is also a method that is bound to the class and not the object of the class. This method can’t access or modify the class state. It is present in a class because it makes sense for the method to be present in class.

class C(object):

@staticmethod

def fun(arg1, arg2, ...):

...

# returns: a static method for function fun.Difference Between Class Method and Static Method

- A class method takes cls as the first parameter while a static method needs no specific parameters.

- A class method can access or modify the class state while a static method can’t access or modify it.

- In general, static methods know nothing about the class state. They are utility-type methods that take some parameters and work upon those parameters. On the other hand class methods must have class as a parameter.

- We use @classmethod decorator in python to create a class method and we use @staticmethod decorator to create a static method in python.

When to use the class or static method?

We generally use the class method to create factory methods. Factory methods return class objects ( similar to a constructor ) for different use cases. We generally use static methods to create utility functions.

Iterables are objects that can return one of their elements at a time, such as a list. Many of the built-in functions we’ve used so far, like 'enumerate,' return an iterator.

An iterator is an object that represents a stream of data. This is different from a list, which is also an iterable, but is not an iterator because it is not a stream of data.

Generators are a simple way to create iterators using functions. You can also define iterators using classes, which you can read more about here.

Here is an example of a generator function called my_range, which produces an iterator that is a stream of numbers from 0 to (x - 1).

def my_range(x):

i = 0

while i < x:

yield i

i += 1Notice that instead of using the return keyword, it uses yield. This allows the function to return values one at a time, and start where it left off each time it’s called. This yield keyword is what differentiates a generator from a typical function.

Remember, since this returns an iterator, we can convert it to a list or iterate through it in a loop to view its contents. For example, this code:

for x in my_range(5):

print(x)

""" outputs:

0

1

2

3

4 """Generators are a lazy way to build iterables. They are useful when the fully realized list would not fit in memory, or when the cost to calculate each list element is high and you want to do it as late as possible. But they can only be iterated over once.

Generator Expressions

Here's a cool concept that combines generators and list comprehensions! You can actually create a generator in the same way you'd normally write a list comprehension, except with parentheses instead of square brackets. For example:

sq_list = [x**2 for x in range(10)] # this produces a list of squares

sq_iterator = (x**2 for x in range(10)) # this produces an iterator of squaresThis can help you save time and create efficient code!