Rust described from the perspective of JavaScript developer.

You could use C, C++, C#, Go, Java, Kotlin, Haskell or a hundred others. Rust is notoriously difficult even for system programmers to get into. Why bother with Rust? Think about your languages as tools in your toolbox. When you fill your toolbox, you don’t want 10 tools that solve similar problems. You want tools that complement each other and give you the ability to fix everything an anything. You already have JavaScript, a developer super-tool. It’s a high level language that’s good enough to run just about everything everywhere. If you’re picking up a new language, you might as well go to the extreme and pick a no-compromise, low-level powerhouse. Also, WebAssembly. Rust’s tooling and support for WebAssembly is better than everything else out there. You can rewrite CPU-heavy JavaScript logic into Rust and run it as WebAssembly. Which basically makes you a superhero. With JavaScript and Rust, there’s nothing you can’t handle. - book "From JavaScript to Rust" written by Jarrod Overson, Vino Technologies, and contributors

In addition to that:

C/C++ level performance, with...

- nice ergonomics and a language server

- automatic memory management

- a package manager and code formatter

- Rust is a big language - there is a whole bunch of stuff to learn.

- Smaller ecosystem than C/C++ (but FFI)

- Slower iteration cycle than most languages

- due to strict compiler

- "fighting" the borrow checker

- slow compile times for full builds

- tests can take awhile to build

There is a number of design decisions some of which are in the name of performance. (TBC)

Rust is programming language that comiples to either machine code (binary executable) or WASM.

- Mozilla (firefox - rendering stuff)

- Microsoft (rewriting some of the core low level windows things)

- Dropbox (perf)

- NextJS 12 (JS/TS Rust based compiler - swc)

fn main() {

println!("Hello, World!");

}

// rustc app.rs

// file ex. - app.rs

fn main() {

let greeting = "Hello";

let subject = "World";

println!("{}, {}!", greeting, subject);

}

// println logs output to the console (supports interpolation as part of its own implementation)

-------------------------------------------------

let subject = "World";

let greeting = format!("Hello, {}!", subject);

// format returns the string

-------------------------------------------------

fn main() {

let crach_reason = "Server crashed.";

panic!("I crashed! {}", crash_reason);

println!("This will never get run");

// panic ends the program (not like ex. throw) - we're exiting right now.

}

- rust-analyzer (matklad.rust-analyzer)

By default, rust-analyzer runs cargo check on save to gather project errors and warnings. cargo check essentially just compiles your project looking for errors.

If you want more, then you’re looking for clippy. Clippy is like the ESlint of the Rust universe. Get clippy via rustup component add clippy.

"rust-analyzer.checkOnSave.command": "clippy"

- Disable inline hints (obviously optional)

"rust-analyzer.inlayHints.enable": false,

"rust-analyzer.inlayHints.chainingHints": false,

"rust-analyzer.inlayHints.parameterHints": false

- Prompt before downloading updates

"rust-analyzer.updates.askBeforeDownload": true

- For debugging pruposes.

vadimcn.vscode-lldb

- Syntax highlighting for TOML files

bungcip.better-toml

- Latest versions of dependencies and quick access to update

serayuzgur.crates

fn main() {

println!("Hello, World!");

}

main()function is required in standalone executables. It’s the entrypoint to your CLI app.println!()is a macro that generates code to print arguments toSTDOUT.macrosare like inline transpilers that generate code during compilation.

Rust uses let and const keywords just like JavaScript, though where you want to use const just about everywhere in JavaScript, you want to use let in most Rust.

Try to run code syntax below (running cargo run from terminal window in Rust project root directory)

fn main() {

let greeting = "Hello, world!"; println!("{}", greeting);

}

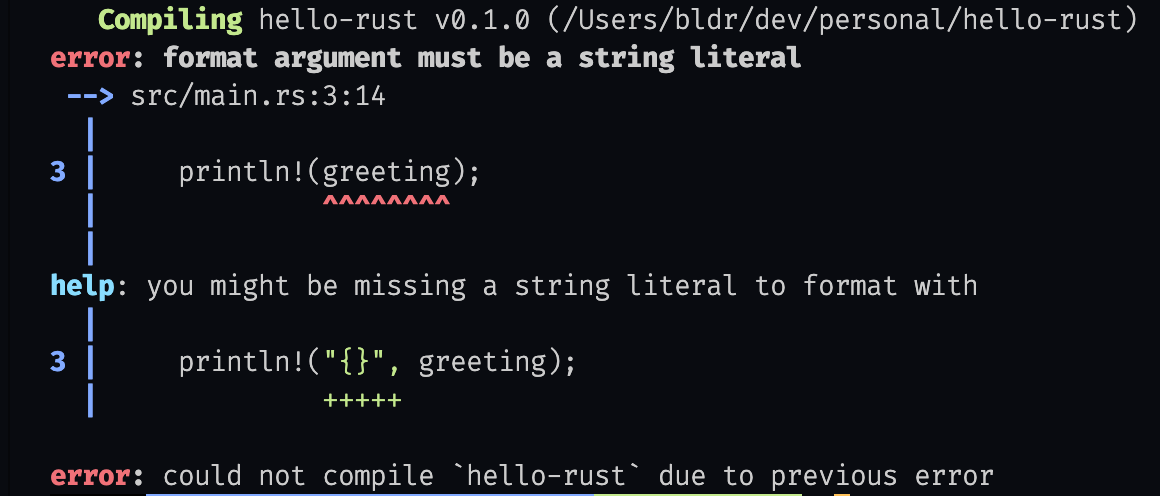

Example of error message in Rust (while running code mentioned above)

Error message is also shown if the IDE is set up as mentioned in p. 7

Who doesn't love refactoring code in the sake of making reusable, perfectly crafted pieces? Try running following example:

fn main() {

greet("World");

}

fn greet(target: String) {

println!("Hello, {}", target);

}

There are indeed two separate string types in Rust (String and str), and although they’re technically different types, they are –for most intents and purposes – the same thing. They both represent a UTF-8 string of characters, stored in a contiguous region of memory.

The only practical difference between String and str is the way memory is managed.

It’s helpful to think about them in terms of how memory is allocated. The two Rust string types can be thought of as such:

str: a stack allocated, immutable, fixed-length UTF-8 string, which can be borrowed as&strand sometimes&’static str, but can’t be moved,String: a heap allocated, growable UTF-8 string, which can be borrow as&Stringand&str, and can be moved

Since the size of str is unknown, you can only handle it behind a pointer. This means that you can only ever interact with str as a borrowed type aka &str - a reference to some UTF-8 data, normally called a "string slice" or just a "slice". This is the preferred way to pass strings around. A slice is just a view onto some data, and that data can be anywhere, e.g.

- In static storage: a string literal "foo" is a &'static str. The data is hardcoded into the executable and loaded into memory when the program runs.

- Inside a heap allocated String: String dereferences to a &str view of the String's data.

- On the stack.

let mut s = String::from("Hello, World!");

println!("{}", s.capacity()); // logs 13

s.push_str("Here I come!");

println!("{}", s.len()); // logs 25

let s = "Hello, World!";

println!("{}", s.capacity()); // compile error: no method named `capacity` found for type `&str`

println!("{}", s.len()); // logs 13

&String - reference to a String, also called a borrowed type. This is nothing more than a pointer which you can pass around without giving up ownership.

&String can be coerced to a &str:

fn main() {

let s = String::from("Hello, World!");

foo(&s);

}

fn foo(s: &str) {

println!("{}", s);

}

In the above example, foo() can take either string slices or borrowed Strings, which is very convenient. As such, you almost never need to deal with &Strings.

In summary, use String if you need owned string data (like passing strings to other threads, or building them at runtime), and use &str if you only need a view of a string.

- Use String anytime you need a mutable string.

- Use str for immutable strings which are known at compile time, or when initializing a String.

- Write functions which accept &str as an argument for strings, unless you need to take ownership of the string, in which case use String.

Where you want const in JavaScript, you want let in Rust. Where you’d use let in JavaScript, you’d use let mut in Rust. The keyword mut is required to declare a variable as mutable (changeable). That’s right, everything in Rust is immutable (unchangeable) by default.

One major difference with Rust is that you can only reassign a variable with a value of the same type.

fn main() {

let mut mutable = 1;

println!("{}", mutable);

mutable = "3"; // Notice this isn't a number.

println!("{}", mutable);

}

That said, you can assign a different type to a variable with the same name by using another let statement

fn main() {

let myvar = 1;

println!("{}", myvar);

let myvar = "3";

println!("{}", myvar);

}