Random let me get through half a cup of coffee before he said, “Tell me about the Ghostwheel.“

“It’s a kind of para-physical surveillance device and library.“

Random put down his cup and cocked his head to one side.

“Could you be more specific?“ he said.

“In other words, I had to locate a shadow environment where the operations would remain pretty much invariant but where the physical construct, all of the peripherals, the programming techniques and the energy inputs would be of a different nature.“

“You’ve lost me already.“

Ghostwheel makes using clojure.spec easy, minimises the need for unit tests, detects unexpected side effects at compile time, and helps you see what your code is doing so that you can play, explore and refactor fearlessly.

It’s about getting the mundane, frustrating stuff out of the way in order to let you focus on the creative side of building software and maybe even get some quality hammock time without cryptic stack traces invading your dreams.

Here are some buzzwords and pictures:

-

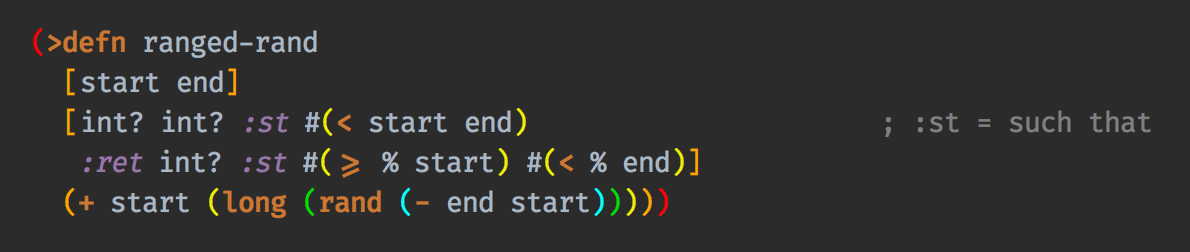

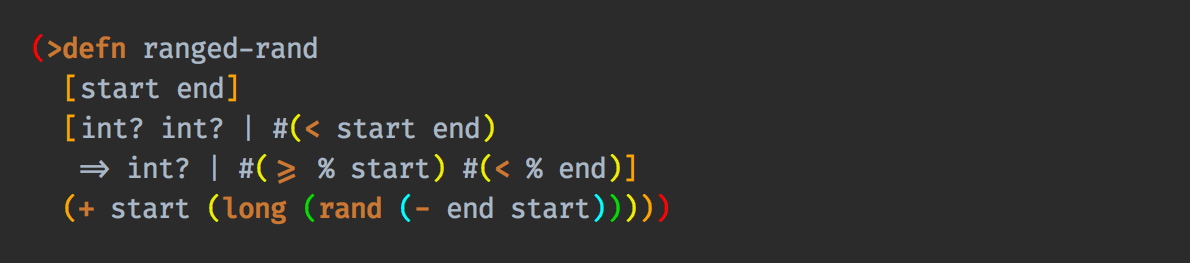

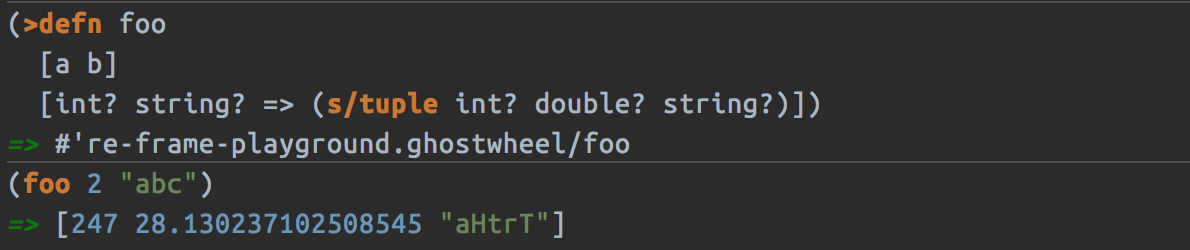

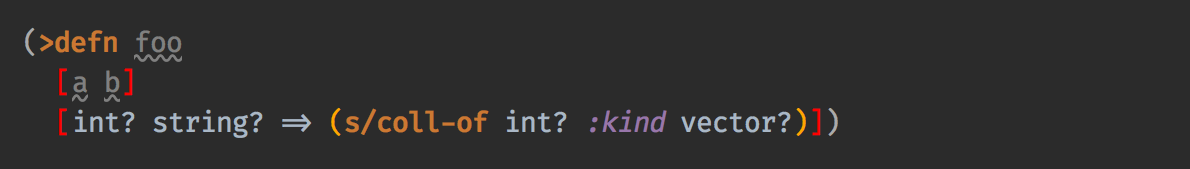

Inline fspec definitions with a concise syntax for single- and multi-arity functions for improved readability and minimal effort spec writing and refactoring

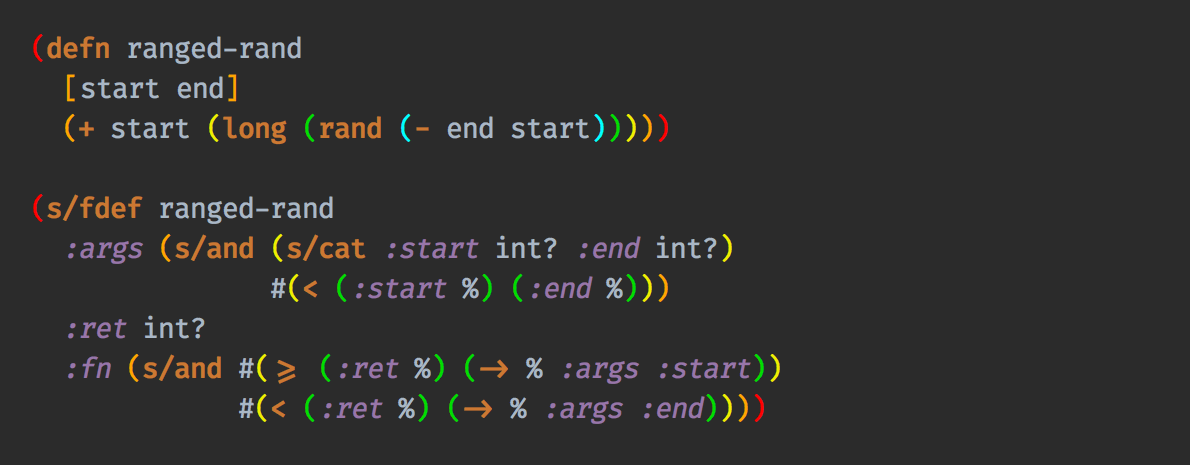

…so instead of writing specced functions like this:

…you can write them like this:

…or using the alternative symbolic operators (with ligatures):

-

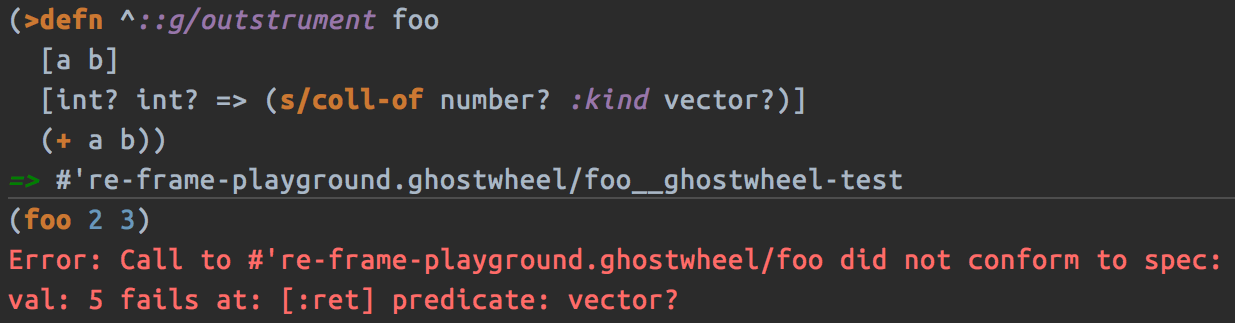

Automagical generative testing – off by default – of specced, side-effect-free functions on namespace reload, with human-readable expound-powered reporting and support for spec instrumentation of internal and external namespaces, including experimental specs for most of clojure.core

-

Explicit side-effect annotations with heuristic compile-time validation (= making sure you stick to naming your unsafe functions with a bang)

-

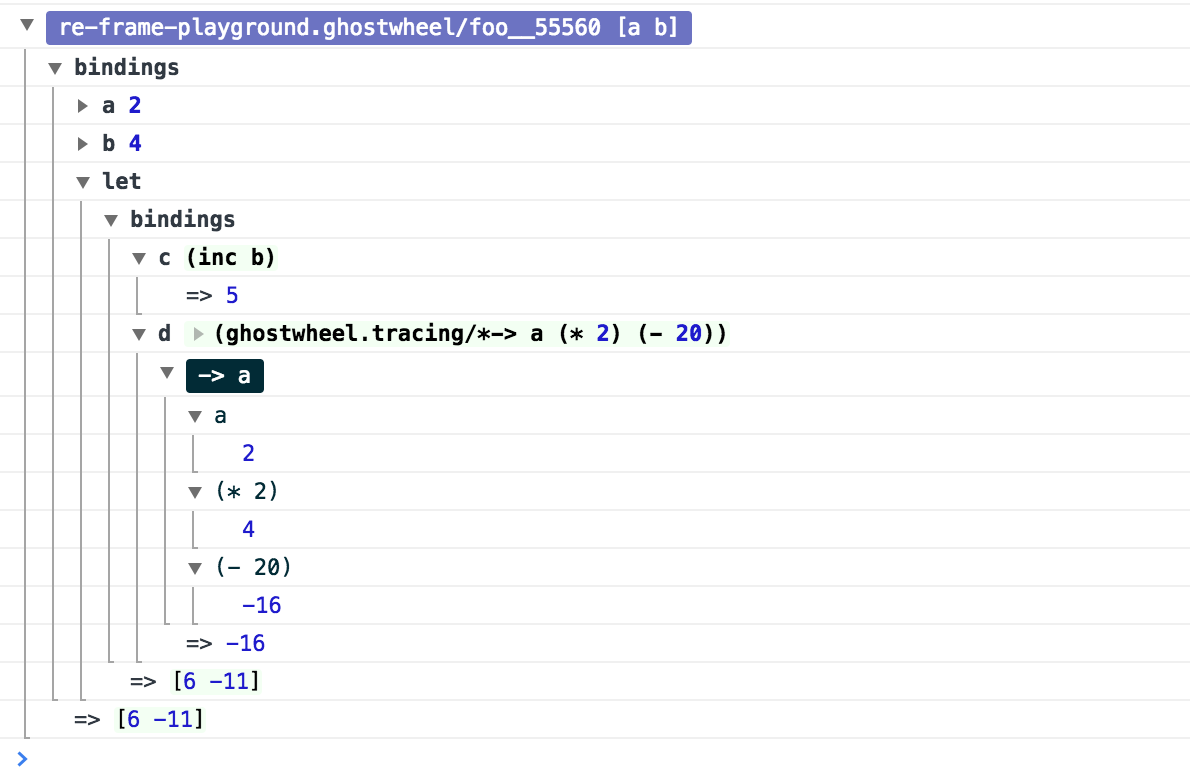

Comprehensive tracing of function I/O, bindings and all threading macros for smooth debugging and exploratory programming

ClojureScript only at the moment.

-

Effortless spec-based stub generation in nil-body functions for rapider prototyping

-

Easy instrumentation of individual functions and namespaces with cljs.spec.test or orchestra on namespace reload

-

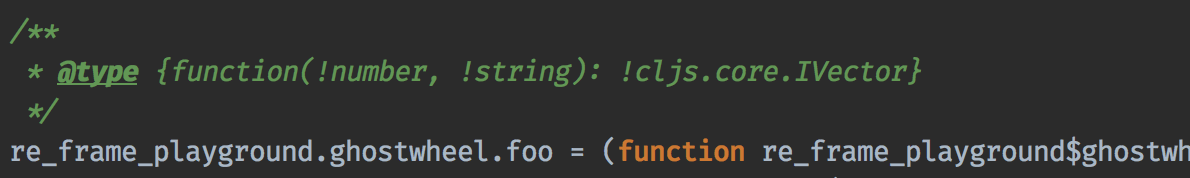

Experimental automatic generation of Google Closure type annotations from fspec definitions

WIP, ClojureScript only.

“There was a button,“ Holden said. “I pushed it.“

“Jesus Christ. That really is how you go through life, isn’t it?“

It’s the age of smartphone notifications, cat videos and Twitter. You are not unlikely to have the attention span of a sleep-deprived parakeet and this walkthrough looks terrifyingly long (it’s just the pictures, really). Here’s your personal read-it/skim-it guide:

Definitely read:

|

🔥

|

← Danger zone. |

|

|

Read this or strange things might happen that’ll freak you out. |

Stuff you simply need to know in order to use Ghostwheel effectively is written as regular text, like this.

Better read:

|

💡

|

Tips and tricks to make the most of Ghostwheel. Not critical but highly recommended. |

Maybe skim:

|

ℹ️

|

This is additional information on how and/or why something works the way it does. Read if you are curious or intend to open an issue and aren’t certain if it’s Ghostwheel’s fault. Otherwise non-essential so feel free to skip or skim it. I’ll be silently judging you. |

-

Install

ClojureScript only – optional, but highly recommended:⚠️ Make sure you use Clojure 1.9.0 or higher and don’t override Ghostwheel’s dependencies with lower versions or you might get strange behaviour. -

Enable

-

On Clojure – launch the REPL / build with the JVM system property

-Dghostwheel.enabled=true -

On ClojureScript – either set

-Dghostwheel.enabled=trueor add:external-config {:ghostwheel {}}to the compiler options in your development build config.🔥Do not enable Ghostwheel in your production build config or you might end up with tracing, testing or instrumentation code in production. When disabled, Ghostwheel doesn’t generate any extra code whatsoever other than simply passing through the plain, unchanged defn.

-

-

Configure

Ghostwheel’s behaviour is determined individually for each function by merging the configuration maps:

ghostwheel.utils/ghostwheel-default-config→ghostwheel.ednconfig file in the project root → compiler options (ClojureScript only) → namespace metadata → function metadata.See the default configuration map for a description of the options – unless explicitly stated otherwise, each one can be overridden on any level.

ℹ️Most of the functionality is disabled by default to avoid any nasty surprises. 💡Note that Ghostwheel uses

ghostwheel.core-qualified keywords for its configuration, except in the top level configuration (ghostwheel.ednor compiler options). To minimise verbosity you can use namespaced maps for the namespace metadata like this:(ns test-chamber.one #:ghostwheel.core{:check true :num-tests 10} ...)

There’s no need for this in the function metadata – if you alias Ghostwheel with

[ghostwheel.core :as g]you can just reference the options as::g/check. -

Use

(:require [ghostwheel.core :as g :refer [>defn >defn- >fdef => | <- ?]])

ClojureScript tracing only – require once, somewhere in your project:(:require [ghostwheel.tracer])ℹ️=>,|,<-and?are optional

25 And the Lord spake unto the Angel that guarded the eastern gate, saying “Where is the flaming sword that was given unto thee?”

26 And the Angel said, “I had it here only a moment ago, I must have put it down somewhere, forget my own head next.”

27 And the Lord did not ask him again.

Function specs are generally defined inline using the >defn macro, except when defining them for functions in external namespaces – mainly for instrumentation – in which case >fdef is used.

>defn is almost identical to defn, except that the first body form must be an inline spec definition using the gspec syntax (to be explained in detail in the next section):

(>defn ranged-rand

"I was lifted straight from the clojure.spec guide"

[start end]

[int? int? | #(< start end)

=> int? | #(>= % start) #(< % end)]

(+ start (long (rand (- end start)))))|

💡

|

Leave out the function body or set it to nil and you get an automatically generated, spec-instrumented stub, which, when passed the correct arguments, returns random data according to the spec. |

|

💡

|

The gspec can be set to nil – in which case no s/fdef block is generated – but it cannot be left out.

|

|

ℹ️

|

Note that the actual parameter symbols are used in the anonymous predicates instead of From the point of view of the programmer and the editor, the function arguments are bound to their respective symbols and can be freely referenced in any expression as expected, including the gspec which is considered just another body form inside the function. |

>fdef is pretty much the same, except for the missing body forms:

(>fdef ranged-rand

[start end]

[int? int? | #(< start end)

=> int? | #(>= % start) #(< % end)])|

💡

|

If you’re using Cursive IDE, it’s probably a good idea to use IntelliJ’s intention actions to tell Cursive to resolve Just place the cursor on |

Specs for multi-arity functions are defined in a similar way. For example, this is what a spec for clojure.core/drop would look like:

(>fdef clojure.core/drop

([n]

[nat-int? => fn?])

([n coll]

[nat-int? (s/nilable seqable?) => seq?]))Same principle when using >defn with multi-arity functions, just add the function bodies.

|

ℹ️

|

Multi-arity functions where the return value specs vary between the different arities are handled correctly using the :fn fspec clause – macroexpand-1 a >defn or >fdef form for details.

|

Sometimes you need to register an fspec under a keyword in the spec registry for use as part of another spec using (s/def ::keyword (s/fspec …)).

Ghostwheel handles this by simply passing a qualified keyword to >fdef instead of a symbol:

(>fdef ::nested-fspec

[i s]

[int? string? => string?])[arg-specs* (| arg-preds+)? => ret-spec (| fn-preds+)? (<- generator-fn)?]

| = :st – such that

=> = :ret – return value, same as in fspec

<- = :gen – generator, same as in fspec

|

ℹ️

|

Throughout this guide the symbolic gspec operators =>, | and <- will be used instead of the equivalent keyword-based :ret, :st and :gen. The two sets are perfectly interchangeable and can even be freely mixed within the same gspec.

|

The number of arg-specs must match the number of function arguments, including a possible variadic argument – Ghostwheel will shout at you if it doesn’t.

arg-specs for variadic arguments are defined as one would expect from standard fspec:

(>fdef clojure.core/max

[x & more]

[number? (s/* number?) => number?])|

ℹ️

|

The The |

? can be used as a shorthand for s/nilable:

(>fdef clojure.core/empty?

[coll]

[(? seqable?) => boolean?])Nested gspecs are defined using the exact same syntax:

(>fdef clojure.core/map-indexed

([f]

[[nat-int? any? => any?] => fn?])

([f coll]

[[nat-int? any? => any?] (? seqable?) => seq?]))In the rare cases when a nilable gspec is needed ? is put in a vector rather than a list:

(>fdef clojure.core/set-validator!

[a f]

[atom? [? [any? => any?]] => any?])|

💡

|

For nested gspecs there’s no way to reference the args in the arg-preds or fn-preds by symbol. The recommended approach here is to register the required gspec separately by using >fdef with a keyword as described in the previous section.

|

|

💡

|

The ghostwheel.specs.clojure.core namespace contains specs for many of the functions in clojure.core. It’s not recommended that you try and instrument it as a whole at this point – there’s a number of ways in which that’s likely to blow up in your face – but it can serve as a good reference on how to write different types of gspecs correctly.

|

|

ℹ️

|

Nested gspecs with one or more any? argspecs desugar to ifn?, so as not to mess up generative testing. This can be overridden by passing a generator – even an empty one, that is simply adding <- or :gen to the gspec – in which case the gspec will desugar exactly as specified. The assumption here is that any? does not imply that the function can in fact handle any type of argument. You should still write out nested gspecs, even if they are as simple as [any? => any?] – this is useful as succinct documentation that this particular function receives exactly one argument.

|

|

ℹ️

|

The gspec syntax has a number of advantages:

|

Set ::g/check and ::g/num-tests to enable generative testing…

(ns re-frame-playground.ghostwheel

#:ghostwheel.core{:check true

:num-tests 10}

...)…and define a simple function:

(>defn addition

[a b]

[pos-int? pos-int? => int? | #(> % a) #(> % b)]

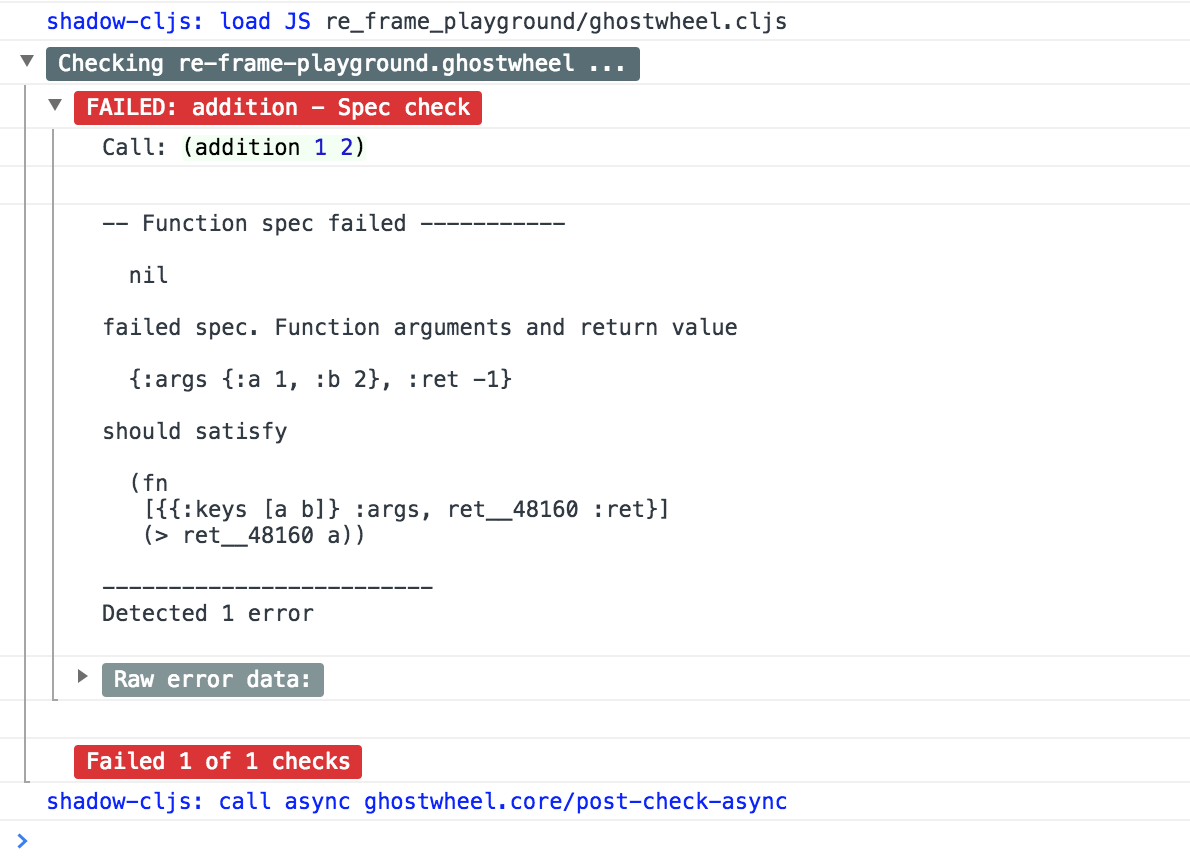

(- a b))This will generate the defn, fdef, and testing code for addition, but it won’t actually run the test. Open the Chrome DevTools console, put (g/check) at the bottom of your namespace and save the file.

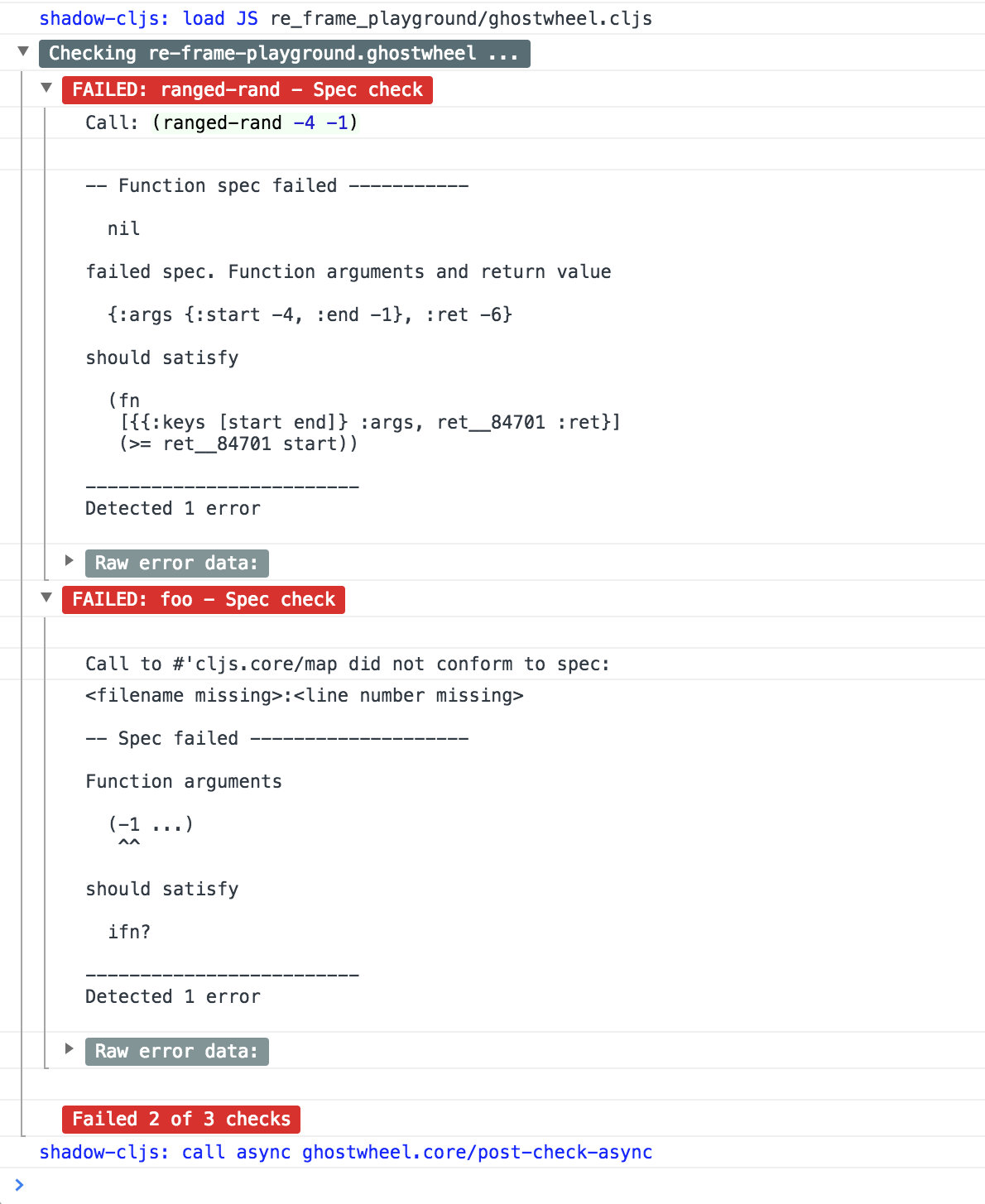

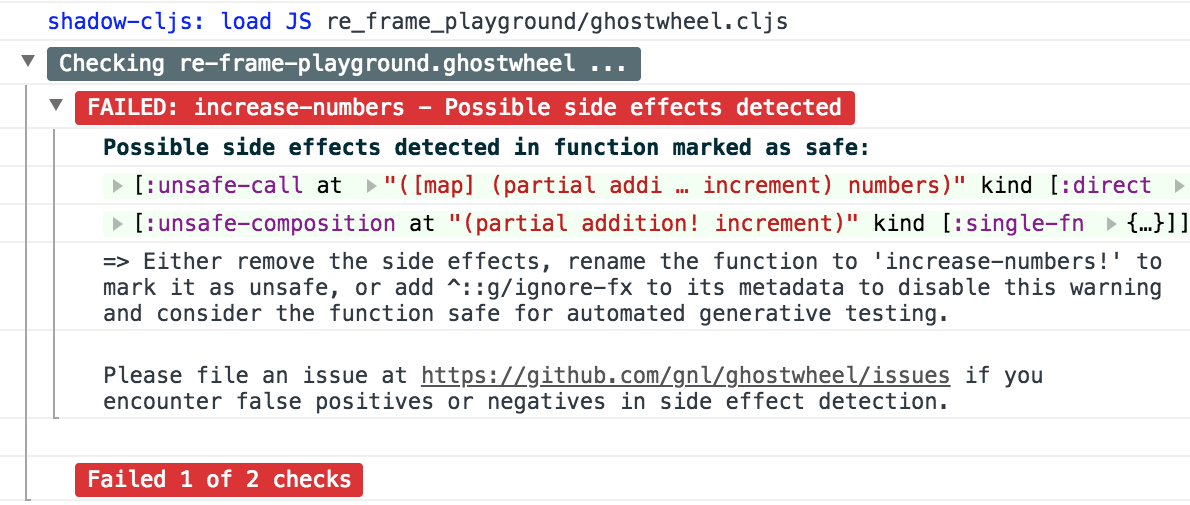

If you have hot-reloading set up correctly and didn’t get too overzealous fixing bugs in the example code before you were told to, you should get something resembling this:

Yay! Ghostwheel is already proving invaluable. Fix it by changing (- a b) to (+ a b), save the file, go back to the console, and rejoice:

|

💡

|

You can test any single or multiple functions or namespaces in the REPL or your test-runner by passing the quoted symbols or namespace regex to |

|

💡

|

You can make re-rendering in a ClojureScript hot-reloading workflow dependent on successful test completion. If you’re using Shadow CLJS you can set the after-load hook like this: The Ghostwheel hook will short-circuit the hook queue if a test fails in any namespace and no re-render will be triggered. |

|

ℹ️

|

In multi-arity functions each arity is tested as a separate function to ensure adequate test coverage, so a function with 3 arities and ::g/num-tests 5 will have 15 spec checks run against it.

|

Depending on the number and kind of functions in a namespace as well as the dependencies between namespaces, even basic testing on every reload could take long enough to make your fancy hot-reloading workflow useless. The general idea here is to keep ::g/num-tests low enough that the tests complete in a reasonable amount of time, but high enough that you still catch a relatively large number of errors on every run.

|

ℹ️

|

Keep in mind that the tests are only executed per namespace reload – whenever (g/check) is called – so if you’re working on some view and hot-reloading its namespace, only the tests defined there (if any) would run. If you change something deep down in a namespace that’s heavily depended on, more namespaces will be reloaded and more tests will run.

|

Either way – you should not be relying on this alone, especially for functions with complex input and a larger number of parameters. Setup a separate test build config just like you would when writing unit tests, enable ::g/extensive-tests, set ::g/num-tests-ext as high as possible without making your test times unacceptable, and run the whole thing in a CI environment or manually on a regular basis – before coffee breaks, merges to master, releases, etc.

Tweak the ::g/num-tests and ::g/num-tests-ext numbers on a global, namespace and function level as needed and feel free to share what worked for you, so the defaults and recommendations can be improved based on more real world data.

“These bridges are made from natural light that I pump in from the surface. If you rubbed your cheek on one, it would be like standing outside with the sun shining on your face. It would also set your hair on fire, so don’t actually do it.“

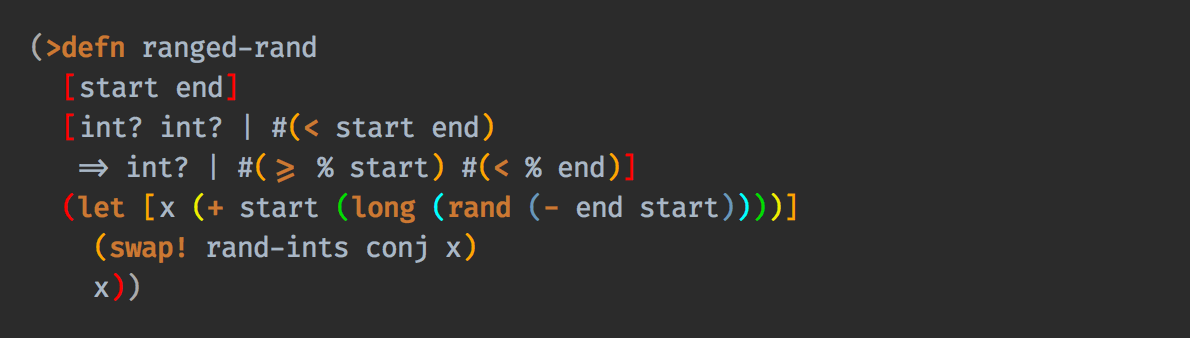

By default functions are considered pure and during compile time Ghostwheel will do its magic to detect potential side effects in any function defined with >defn – calling functions with an ! at the end, do blocks, multiple-form when, let and defn/fn, known unsafe operations, stuff like that – and store the evidence so that it can politely inform you of your transgressions during testing.

It won’t run any automatic generative tests if a function is found to be unsafe, whether it’s due to detected side effects or explicit annotation.

|

ℹ️

|

Ghostwheel assumes functions to be (STM- and test-) safe by default, that is – not having unsafe/permanent side effects, which isn’t necessarily the same thing as pure. For the purpose of this guide we will however use the terms interchangeably, to the absolute horror of purists everywhere. |

You can disable side effect detection with the ::g/ignore-fx option in which case Ghostwheel will simply trust the name of the function (…! = unsafe) and behave accordingly.

|

🔥

|

If you set ::g/ignore-fx true for an actually unsafe function that has been incorrectly named as safe, and have ::g/check enabled, ::g/num-tests set to > 0 as well as a valid gspec and a call to (g/check) at the bottom of the namespace, generative testing will be performed, side effects and all. This could be bad.

|

|

🔥

|

Side effect detection is a heuristic and in no way fail-safe operation, relying heavily on the assumption that you’re not actively trying to shoot yourself in the foot. That being said, so far it seems to work pretty great in practice, and where it occasionally fails, the likelihood of false positives is significantly higher than that of false negatives so the chances of side effects actually seeping through the cracks and setting your hair on fire are relatively low. |

This is pretty much the gist of it – read on for a more detailed description of what all this looks like in practice.

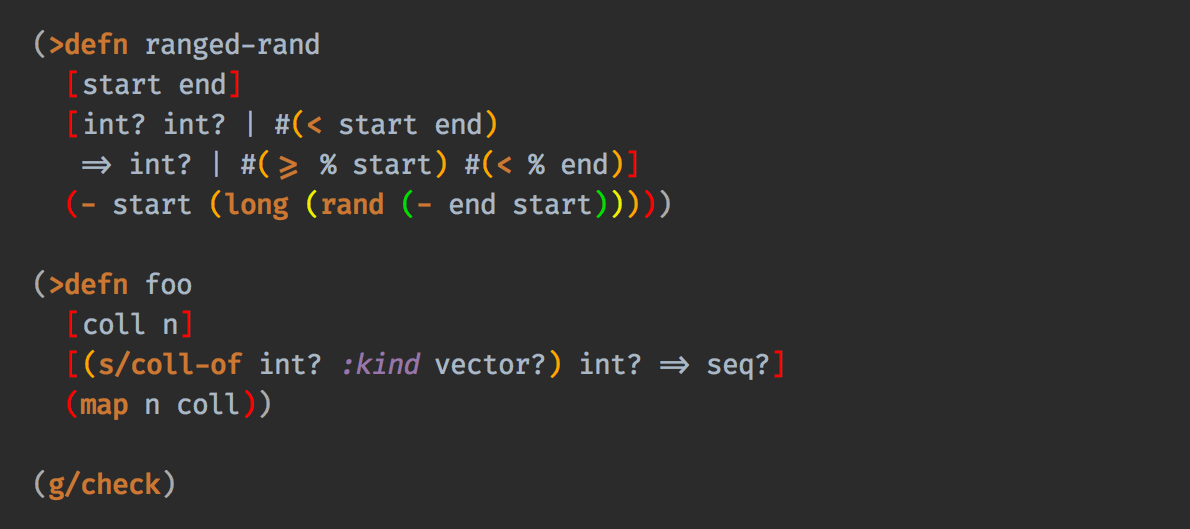

Let’s take the function we defined in the previous section and map it over a collection of numbers, but make sure you have ::g/check and ::g/num-tests set correctly first.

(>defn addition

[a b]

[pos-int? pos-int? => int? | #(> % a) #(> % b)]

(+ a b))

(>defn increase-numbers

[increment numbers]

[int? (s/coll-of int?) => (s/coll-of int?)]

(map (partial addition increment) numbers))

(g/check)The two should check out fine:

We will then decide that it’s a good idea to send an email every time two numbers are added together and modify addition accordingly:

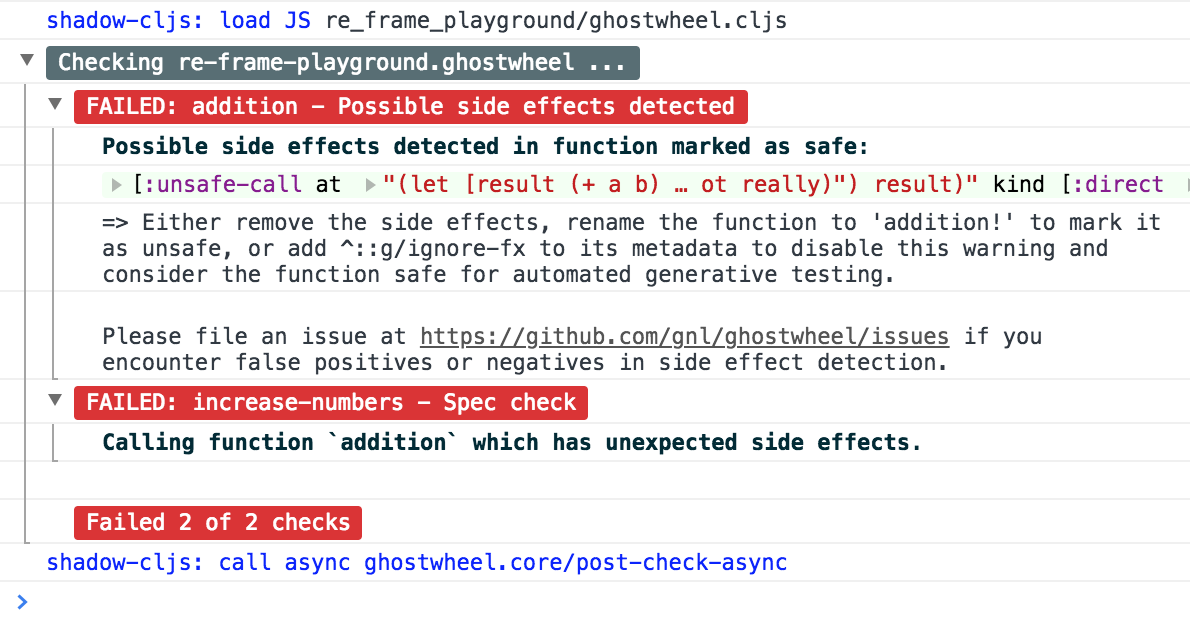

(>defn addition

[a b]

[pos-int? pos-int? => int? | #(> % a) #(> % b)]

(let [result (+ a b)]

(println "Sending mail with" result "(not really)")

result))So that didn’t go too well. Both addition and its caller increase-numbers fail their checks – addition because of the detected side effects, and increase-numbers because it’s calling the former, the body of which is now replaced with exception-throwing code until the whole messy situation is remedied.

|

ℹ️

|

The whole "replaced with exception-throwing code" thing does sound kinda scary, admittedly, but it’s necessary – otherwise, while addition may fail its side effect checks and thus be excluded from testing, increase-numbers would still be happily passing its own, calling addition and sending out mails.

|

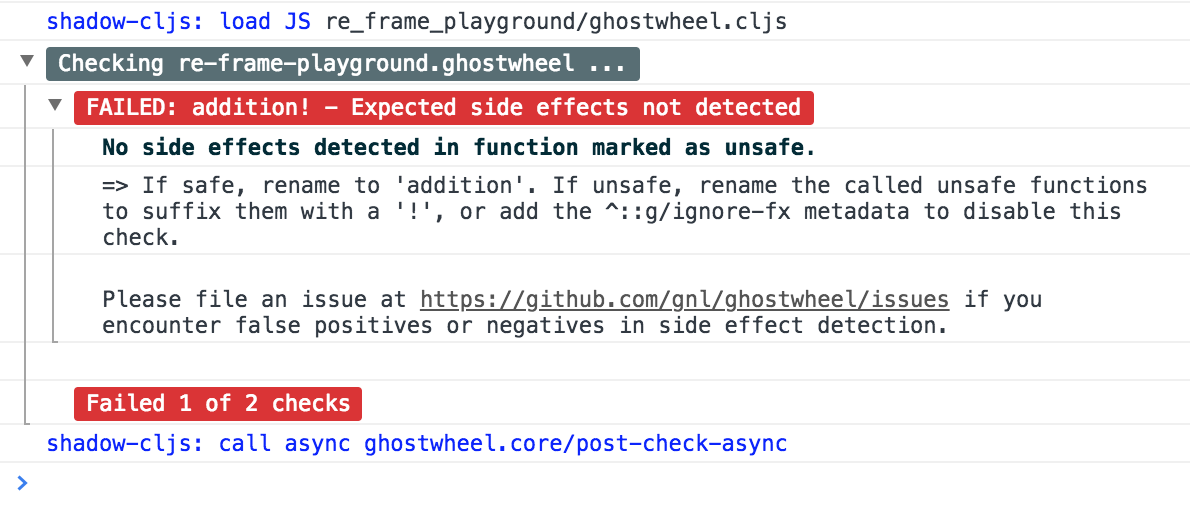

If you’re serious about the impurity, traitor to the Church of Functional Programming that you are, you can make Ghostwheel shut up by renaming your function to suffix it with a ! thus officially marking it as unsafe. Use your IDE to rename addition to addition! now.

Okay, so it doesn’t quite shut up yet, but it’s for your own good. Even though Ghostwheel is now happy about addition! being correctly marked as unsafe, the infestation of impurity is still actively spreading to its callers!

Worry not – Ghostwheel will help you nip this insidious corruption in the bud. Correctly naming an unsafe function will cause all the previously innocent pure functions, which were calling the now branded offender in good faith, to fail their purity inspections as well and be given a chance for redemption. Go ahead and rename increase-numbers to increase-numbers!.

Don’t be too quick to breathe a sigh of relief. The checks are fine, but that’s just because all the side-effectful stuff is out in the open – as mentioned above, no generative testing is being done so whether your impure functions are doing what you think they’re doing is anyone’s guess. Not great, but that’s what you get for messing with the dark side.

|

ℹ️

|

That being said, some work’s being done to make the testing and stubbing of side-effectful functions easy as well, but we ain’t there yet. |

Having recognised the error of your ways, please go ahead and remove the side effect from addition!:

(>defn addition!

[a b]

[pos-int? pos-int? => int? | #(> % a) #(> % b)]

(let [result (+ a b)]

result))To preserve the balance in the universe, purity can spread just as efficiently as its sinister counterpart – if you remove side effects from a function, Ghostwheel will warn you if it’s still marked as unsafe and as soon as you rename it to remove the bang, it will now show the same warning for its potentially purified callers, and so on, until harmony is restored. Once you’ve renamed increase-numbers! as well, this should be the result:

This is nice. You can relax now. If any false positives/negatives come up, just add ::g/ignore-fx true to the function metadata to disable side effect detection and open an issue on github to help improve it.

In fact, the mere act of opening the box will determine the state of the cat, although in this case there were three determinate states the cat could be in: these being Alive, Dead, and Bloody Furious.

Specs are all nice and good, but often enough we want to take a peek at what’s going on under the hood while it’s going. Set the ::g/trace option to anything from 0 to 5 to determine the trace verbosity and performance impact, and you’re good to go.

| Trace level | What gets traced (additive) | What it’s good for |

|---|---|---|

0 |

Nothing |

Production |

1 |

The function call is logged without any data |

Render functions |

2 |

Function I/O |

Event handlers |

3 |

Local bindings |

General debugging |

4 |

Threading macros |

Better debugging |

5 |

Anonymous functions |

Noisy debugging |

|

💡

|

::g/trace true is equivalent to ::g/trace 4, so you can just add the ^::g/trace metadata to the function name.

|

|

💡

|

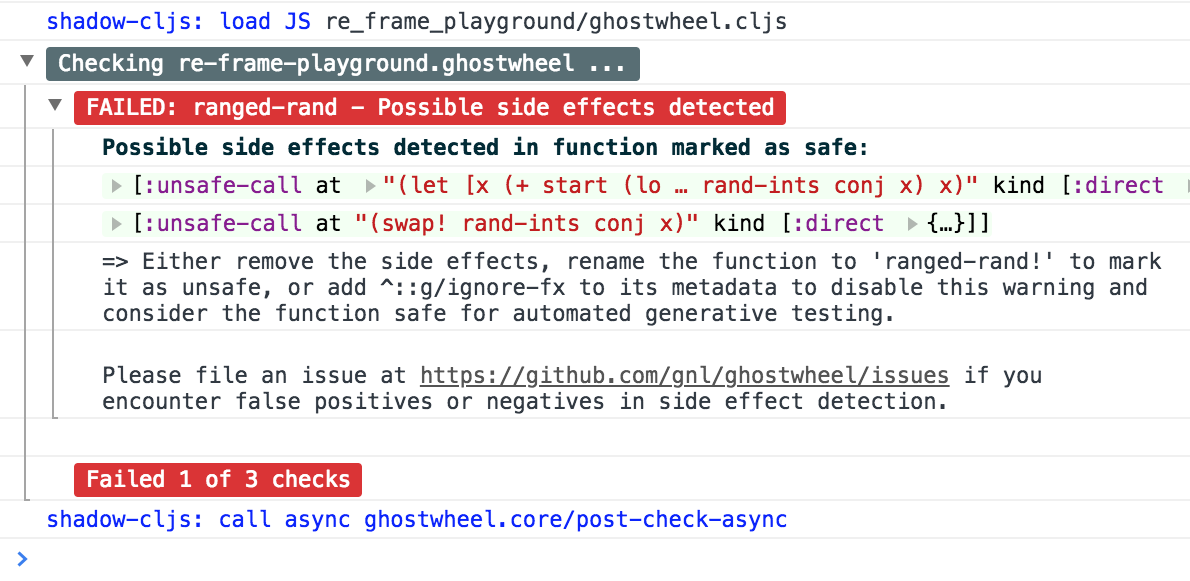

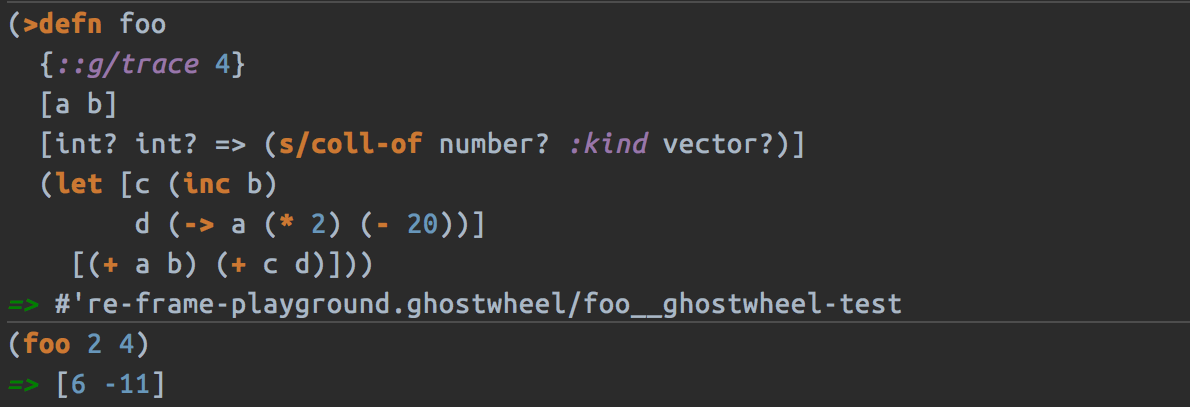

A great workflow for working on a function is enabling the trace and passing a callback to (>defn ^::g/trace foo

[a b]

[int? int? => (s/coll-of number? :kind vector?)]

(let [c (inc b)

d (-> a (* 2) (- 20))]

[(+ a b) (+ c d)]))

(g/check #(foo 2 4))For this to work you’ll also have to set your build system hooks correctly. This way you immediately see data flowing through the function on file save after every change (or the check results, if you messed up). Take a moment to zen out and revel in the intoxicating sense of power. |

|

💡

|

If you don’t like the painstakingly selected default shade of blue-violet, you can change it with the ::g/trace-color option. Philistine.

|

“I USHERED SOULS INTO THE NEXT WORLD. I WAS THE GRAVE OF ALL HOPE. I WAS THE ULTIMATE REALITY. I WAS THE ASSASSIN AGAINST WHOM NO LOCK WOULD HOLD.“

“Yes, point taken, but do you have any particular skills?“

The blood of generations of LISPers is coursing through your veins? You’ve howled naked at the moon in arcane rituals ordained by the dark forces you summoned in order to gain your abilities? At this point you don’t even see the parens?

Or maybe you just like breaking things and telling people about it. Either way, there’s enough work to go around. First and foremost:

-

Put it to use and report any issues you run into

-

Submit PRs with gspecs for external libraries to the ghostwheel.specs repo

Other than that, here’s the rather loose roadmap, not necessarily sorted by priority or particularly rich on detail. PRs are welcome if anything should tickle your fancy (or annoy the hell out of you), but if you are planning on doing anything bigger maybe open an issue first so we can discuss it.

-

Automatically re-run failed gen-tests with tracing enabled.

-

Enable spec-based generation of safe stubs for gen-testing unsafe functions

-

Solve miscellaneous issues around fully instrumenting the

ghostwheel.specs.clojure.corenamespace during testing -

Get the Closure type annotations working properly

-

Integrate bhauman/spell-spec

The quickest and easiest way is probably to use Shadow CLJS and copy an external namespace into the src directory with the correct directory structure – it will then override whatever’s on the classpath. See the Shadow CLJS guide for details.

For a more solid environment - setup a playground project with something like re-frame, link your Ghostwheel repo under the checkouts folder and add checkouts/ghostwheel/src to the source path. This way Shadow CLJS will watch the Ghostwheel namespaces for changes as well and hot-reload accordingly.

A similar setup should be possible with Figwheel as well – feel free to contribute documentation for that if you’re using it.

For debugging the code generating functions in ghostwheel.core there’s a code block at the bottom of the namespace which you can use to trace them at runtime in ClojureScript. Some of the symbol generation here and there can trip it up, but it generally works quite well.

-

Q: Can I trust Ghostwheel not to break my code?

A: Every build is extensively tested with a combination of manually written and generated tests for a large number of configuration option combinations (including all tracing levels) with production and development build configurations in three environments - Clojure, node, and headless Chrome. The generated code is evaluated to make sure it behaves exactly like the code that went in and the fspec generation is tested with a number of convoluted gspecs to make sure everything desugars as expected.

In production mode with Ghostwheel disabled, the gspec vectors are simply stripped from the

>defnblocks and a plaindefnis generated, independent of any other configuration. There are less than 20 lines of Ghostwheel code involved in this scenario and they are also unit-tested to ensure that the produceddefnis identical to the>defnminus the gspecs.>fdefandg/checksimply output nil.Test coverage for the somewhat less critical parts (testing, instrumentation, etc.) is not yet 100% but getting there.

Purely cosmetic bugs in tracing and reporting are more difficult to test and thus more likely.

All that being said, Ghostwheel is Alpha software and you should proceed with care, especially on Clojure where it’s even more Alpha.

-

Q: Can I use Ghostwheel for test generation with existing fspecs defined with

s/fdef?A: Adding support for this was considered and ultimately decided against for the time being. It would add complexity and a maintenance workload in order to enable the use of a small subset of Ghostwheel’s functionality in a subpar manner, because there’s a number of checks and validations Ghostwheel cannot perform without the inline gspecs, and some aspects of its behaviour would change as well.

You can still use Ghostwheel with nil gspecs and take advantage of the side effect detection, tracing functionality and easy instrumentation. Extracting the test generation code into a separate library may be considered further down the line.

What is on the roadmap however, is the ability to convert fspecs to gspecs for an easier migration of existing code bases.

-

Q: What does tracing have to do with testing and why is it not a separate project?

A: Primarily because tracing needs to be aware of the automated testing so as not to interfere with it. That aside, I rely heavily on both spec-checking and tracing in my own workflow and like having the UI tightly integrated like this.

If you’re only interested in tracing you can use

>defnwith nil gspecs and the default configuration plus a per function^::g/trace. There are also some vague plans in the works to involve tracing in the testing process, but that’s still taking shape. -

Q: How are

>defnand>fdefpronounced in conversation?A: Ghostwheel-def-n / g-def-n and ghostwheel-f-def / g-f-def respectively.

-

Q: Why not use a statically typed language?

A: Not touching that one with a ten foot pole.

Ghostwheel builds on clojure.spec, expound, orchestra, clairvoyant, re-frame tracer, and lambdaisland’s uniontypes.

Some other projects and people without which/whom it likely wouldn’t exist in its current form or at all, in no particular order:

plumatic’s schema for offering a glimpse into the future of generative testing for quite some time before spec was introduced;

Thomas Heller’s Shadow CLJS and Bruce Hauman’s Figwheel – for providing robust hot-reloading which is essential to ClojureScript development and to the Ghostwheel experience in particular;

BinaryAge’s CLJS DevTools, without which ClojureScript tracing and data inspection would be a lot less fun;

Philip Kamenarsky for introducing me to Clojure and Haskell, providing valuable feedback during the development of Ghostwheel, and many insightful conversations about some of the concepts that inspired it;

David Nolen for his initial work and documentation on integrating Google Closure type checking and his work on ClojureScript in general;

And last but not least, our cherished BDFL and his minions, working tirelessly to bestow upon us the magic of Clojure, without which Ghostwheel would be somewhere between significantly more difficult to write and plain impossible.

The demon hath return’d from the darkest depths of the underworld, whither he was banish’d when he dared raise his crooked hand against the Macro. His soul – wrapp’d in shadows, his mind – clouded, full of evil and despair. He is the AntiLISP. He speaketh with a twisted tongue and casteth confusion with his words – sweet and cunning – about types and proofs.

Hearken! Raise your armies! Sharpen your parens and gather your bravest heroes! War is upon us.

Clojure is beautiful. The simplicity, clarity, flexibility and immediacy of it; immutable data, macros, the powerful REPL, paredit/parinfer, STM, the list goes on.

On the other hand, the lack of easy, comprehensive type verification before spec came along, sometimes meant frustrating time spent hunting down pointless runtime exceptions – with stack traces and error messages ranging from not particularly helpful to openly mocking – and less willingness to do major refactoring for justified fear of breaking something not immediately visible and painful to debug.

When making changes to any medium sized codebase, one could, despite being careful and having the best of intentions, end up with a less than stellar experience.

In this context spec is a huge step forward and elevates Clojure onto a whole new level of robustness, maintainability, and painless usability. And it does so the Clojure way - by providing simple and powerful tools, making their application easy and natural, and getting out of the way, leaving it up to the programmer to decide how and to what extent they want to use them.

When it comes to defining function specs, however, it’s quite verbose and the actual day to day usage is a little rough around the edges. The gspec syntax was born as a solution, taking inspiration from some static type systems and mathematical notation, while staying Clojure-like enough to be a seamless fit.

Generating the nil-body stubs and automatically defining the tests naturally followed from there, which in turn inspired the heuristic side effect detection to serve as a safeguard against inadvertently doing I/O during testing and to provide additional insight into the code by helping keep unsafe operations explicit.

It is my hope that Ghostwheel will help lower the barrier to using spec and contribute to its wider adoption, which will reduce the need for writing unit tests to a minimum and generally do wonders for overall Clojure code quality.

While spec provides the ability to quickly track down many type and logic errors, it doesn’t remove the need to observe the function in operation, as a tool for both debugging and thinking. Common techniques for achieving this include:

-

running code fragments in the REPL for parts of a function that one wants to see in action, which can force one to create intermediate mock data (which may or may not be an accurate representation of the original environment) or to break functions and bindings apart beyond the point where it would make sense from a complexity/readability perspective;

-

interspersing logging statements throughout the code and sometimes forgetting them there or breaking something along the way and introducing weird bugs, not to mention the hassle of adding and removing them while trying to zero in on the point of interest;

-

setting breakpoints and using a step-by-step debugger, which can be quite akin to trying to take in a landscape through a straw.

Compared to these, seeing the data as it flows through each part of a function at a glance in a tree of evaluated expressions is quite a bit more efficient, enjoyable, and conducive to thinking about the operations and architecture involved on a higher level.

Essentially, Ghostwheel is about reaching a higher state of flow by removing the barriers between your mind and your code, and taking a lot of pedestrian busywork off your shoulders to put it where it belongs – with the computer.

Now go forth and create, fellow maker. Use your new-found powers for good.

Copyright (c) 2018 George Lipov

Licensed under the Eclipse Public License 2.0