A password strength calculator that does things properly.

Most password strength meters are terrible. They check for a capital letter, a number, and call it a day. This one uses real cryptographic research, actual GPU benchmarks, and breach data to tell you how long your password would actually take to crack.

Sponsored by Upon: Digital Inheritance Vaults.

Traditional password meters reward complexity theater: swap an a for @, add a 1 at the end, and suddenly you're "strong." But attackers aren't stupid. They know about l33tspeak. They have dictionaries of common substitutions. "P@ssw0rd!" isn't 9 random characters drawn from 95 possibilities, it's a predictable mutation of the #4 most common password on the internet. In fact, it's been breached 120k times and is likely one of the first passwords an attacker will try!

We combine three signals to estimate how quickly an attacker could crack your password:

- Pattern analysis: zxcvbn decomposes your password into dictionary words, keyboard patterns, and substitutions, then estimates how many guesses it would take.

- Breach data: we check Have I Been Pwned to see if your password has leaked, then apply a Zipf's law penalty based on how often it appears.

- Real hardware benchmarks: we use actual RTX 5090 hashcat speeds to show crack times across different hash algorithms and attacker resources.

The final entropy is the minimum of the pattern-based estimate and the breach-based estimate. A password in an attackers list from previous breaches is effectively worthless, no matter how random it looks.

Entropy measures uncertainty, expressed as the number of guesses an attacker would need to find your password. We measure it in bits, where each bit doubles the search space:

| Bits | Possible Combinations | Equivalent To |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1,024 | 4-digit PIN with letters |

| 20 | ~1 million | Weak password |

| 40 | ~1 trillion | Moderate password |

| 60 | ~1 quintillion | Strong password |

| 80 | ~1 septillion | Very strong password |

Mathematically, entropy is the base-2 logarithm of guesses needed, assuming an attacker tries passwords in optimal order. If you pick randomly from a character set of size N for L characters, entropy = L × log₂(N). A 10-character lowercase password has 10 × 4.7 ≈ 47 bits.

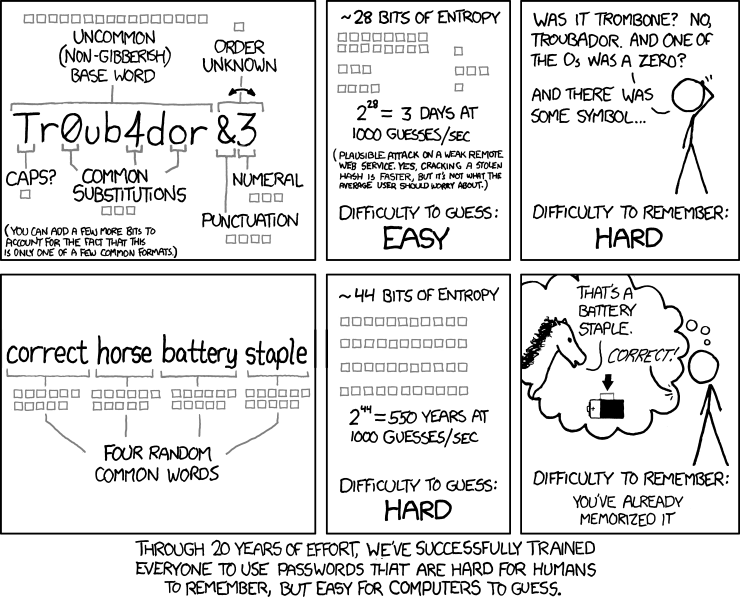

Humans don't pick randomly, though. We use words, patterns, and substitutions that drastically reduce the effective entropy. xkcd #936 illustrates this perfectly:

The comic shows "Tr0ub4dor&3" at ~28 bits versus "correct horse battery staple" at ~44 bits. The complex-looking password is actually weaker. The number of guesses matters, not how "random" it looks to a human.

We use zxcvbn-ts, a TypeScript port of Dropbox's zxcvbn library. Instead of the naive approach (entropy = log₂(charset_size) × length), zxcvbn models how attackers actually crack passwords:

- Dictionary attacks – Checks against common passwords, English words, names, and surnames

- Keyboard patterns – Recognizes "qwerty", "zxcvbn", and "123456"

- Repeated characters – "aaaaaaa" isn't 7 characters of entropy

- Sequences – "abcdef" and "13579" are predictable

- L33t substitutions – "@" for "a", "0" for "o", "$" for "s"

- Dates – Birthdays and anniversaries are common password components

zxcvbn estimates the number of guesses an attacker would need by finding the lowest-cost decomposition of your password into known patterns, which we can then convert into bits via entropy = log₂(guesses).

zxcvbn accurately estimates entropy for human-created passwords but tends to underestimate truly random passwords. For example, "Hn@q8kKYN*" has ~60 bits of true entropy based on its character set, yet zxcvbn estimates only ~33 bits.

Even a randomly-generated password becomes worthless if it's in a breach database. Attackers don't brute-force from scratch, they start with lists of known passwords, sorted by frequency. Your clever passphrase might be unique in your head, but if it leaked from Adobe in 2013, it's in every attacker's wordlist.

We check passwords against Have I Been Pwned's database of 850+ million compromised passwords without ever sending your password over the internet.

HIBP stores SHA-1 hashes of every leaked password in their database, which we query using a protocol called k-anonymity:

- We SHA-1 hash your password locally (e.g.

password123becomesCBFDAC6008F9CAB4083784CBD1874F76618D2A97) - We send only the first 5 characters of the hash to HIBP (

CBFDA) - HIBP returns ~500 hash suffixes that match that prefix

- We check locally if our full hash suffix is in the list

The server never sees your password or even its full hash. The 5-character prefix matches ~500 other hashes, providing plausible deniability. We also use the Add-Padding: true header to prevent response length analysis.

If your password appears in 10,000 breaches, how much does that actually hurt you?

Attackers don't try passwords randomly. They try them in order of popularity, and password frequency distributions follow Zipf's law, the same power law that governs word frequency in natural language. The most common password is tried first, the second most common second, and so on. A password that appears twice as often gets tried much earlier, not just a little earlier.

Research on password distributions ("A Large-Scale Study of Web Password Habits" and subsequent analysis) suggests that password frequency follows:

frequency(rank) = C / rank^s

We use the exponent s ≈ 0.78 for passwords as per the research papers. Inverting this formula lets us estimate rank from frequency:

rank = (C / frequency)^(1/s)

entropy = log₂(rank)

We use pessimistic parameters: C = 1,000,000, anchored to "password" appearing roughly 1 million times in breaches. This aligns with leaked datasets like RockYou and Collection #1, where the most common passwords appear millions of times.

| Breach Count | Estimated Rank | Entropy (bits) |

|---|---|---|

| 42,000,000 | ~1 | ~0 |

| 1,000,000 | ~1 | ~0 |

| 100,000 | ~19 | ~4.2 |

| 10,000 | ~363 | ~8.5 |

| 1,000 | ~6,918 | ~12.8 |

| 100 | ~132,000 | ~17 |

| 10 | ~2,500,000 | ~21.3 |

| 1 | ~48,000,000 | ~25.5 |

We also apply a hard cap of 25 bits for any breached password. Even if a password only appears once in a breach, the attacker's wordlist is only ~1 billion entries (log₂(1 billion) is ~30 bits of entropy) and we want to be conservative.

The crack time table uses real-world benchmarks from hashcat running on an NVIDIA RTX 5090 (the current fastest consumer GPU for password cracking). Sources:

- RTX 5090 hashcat benchmarks by Chick3nman

- RTX 4090 benchmarks for comparison

- Argon2id benchmarks from hashcat 7.0.0

| Algorithm | RTX 5090 Speed | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MD5 | 220.6 GH/s | 220 billion attempts per second |

| SHA-1 | 70.2 GH/s | Still catastrophically fast |

| SHA-512 | 10 GH/s | Faster than you'd expect |

These are message digests, not password hashes. They're designed to be fast, which is exactly wrong for password storage. If you see a site storing passwords as MD5... run. Even with salts, fast hashes remain unsafe because attackers can still test billions of guesses per second per account.

KSFs are specifically designed to be slow, memory-hard, or both. We benchmark with production-realistic parameters:

| Algorithm | Parameters | RTX 5090 Speed |

|---|---|---|

| PBKDF2 | 310,000 iterations (Django 4.x default) | ~36 kH/s |

| bcrypt | cost 10 (1,024 rounds) | ~9.5 kH/s |

| scrypt | N=16384, r=1, p=1 | ~7.8 kH/s |

| Argon2id | m=64MiB, t=3, p=1 (RFC 9106) | ~2.2 kH/s |

Argon2id is the current recommendation from the Password Hashing Competition. It's memory-hard, requiring 64MB of RAM per hash attempt, which makes GPU parallelization expensive. The parameters we use match the "first recommendation" from RFC 9106.

The table shows crack times across different attacker resources:

- 1 GPU: Individual attacker or researcher

- 10-100 GPUs: Small organization or dedicated attacker

- 1,000-10,000 GPUs: Large corporation or criminal enterprise

- 1,000,000 GPUs (Nation State): Theoretical upper bound rather than any known deployed system in 2025

For a given password, the time to crack is:

average_time = (2^entropy) / (2 × hash_rate × gpu_count)

We divide by 2 because on average, you'll find the password halfway through the search space.

A 12-character random password using lowercase letters and digits has about 62 bits of entropy. Here's how crack times differ based on how the site stores your password:

| Storage Method | 1 GPU | 10k GPUs | Nation State |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD5 | 105 years | 4 days | Instant |

| Argon2id | 66M years | 6.6k years | 66 years |

The same password, stored properly, goes from being crackable by a well-funded attacker to almost impossible to crack.

- Use a password manager: randomly generate every password except your master password.

- Entropy beats complexity theater: 4 random dictionary words ("correct horse battery staple") outperform complex-looking mutations ("Tr0ub4dor&3") because attackers know about l33tspeak.

- Check your passwords against breaches: if it's leaked, it's worthless, no matter how random it looks.

- Use unique passwords everywhere: credential stuffing means one breach compromises all accounts sharing that password.

- Demand proper password storage: Use a strongly configured key stretching function like Argon2id (ideally with PAKE such as OPAQUE and per-user salts). If a service stores your password with MD5 or SHA, they are failing you.

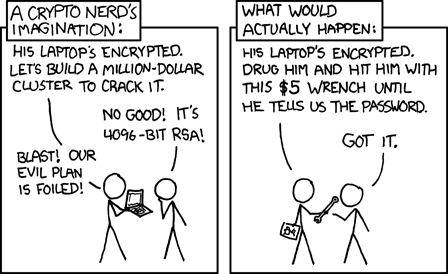

- 80+ bits of entropy remains out of reach, even for nation-states with theoretical million-GPU clusters. But don't forget rule #538: