Python's built-in None constant may not be sufficient to distinguish situations where a value is undefined from situations where it is defined as undefined. Does that sound too abstract? Then read below the more detailed description of the problem and what solutions exist for it.

Programmers encounter uncertainty everywhere. We don't know in advance whether a user will enter a valid value into a form, or whether a given operation on two numbers is possible. To highlight uncertainty as a separate entity, programmers have come up with so-called sentinel objects. These can be very different: NULL, None, nil, undefined, NaN, and an infinite number of others.

Different programming languages and environments offer different models for representing uncertainty as objects. This is usually related to how a particular language has evolved and what forms of uncertainty its users most often encounter. Globally, I distinguish three main models:

-

One simple sentinel object. This approach works great in most cases. In most real code, we don't need to distinguish between more than one type of uncertainty. This is the default model offered by Python (although there is much room for debate here: for example, exceptions can, in a sense, also be considered sentinel objects). However, it breaks down when we need to distinguish between situations where we know we don't know something and situations where we don't know that we don't know something.

-

Two sentinel objects. This is more common in languages where, for example, a lot of user input is processed and where it is necessary to distinguish between different types of empty values. If our task is to program Socrates, that will be quite sufficient.

-

An infinite recursive hierarchy of sentinel objects. From a philosophical point of view, uncertainty cannot be considered as a finite object, because that would already be a definite judgment about uncertainty. Therefore, we should consider uncertainty as consisting of an infinite number of layers. In practice, such structures can arise, for example, when we extract data from a large number of diverse sources but want to clearly distinguish at which stage of the pipeline the data was not found.

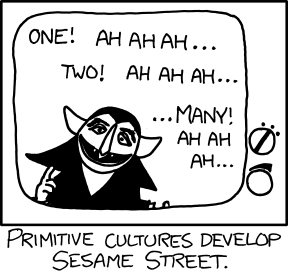

Yes, this library was also created by primitive cultures

The first option is almost always sufficient. The denial library offers special primitives that cover the second and third options, providing complete coverage of uncertainty options for Python:

- The first option is built into Python and does not require any third-party libraries:

None. - The second option is represented by the

InnerNoneconstant fromdenial. It is practically the same asNone, just a secondNone. - For the most complex cases, you can create your own sentinel objects using the

InnerNoneTypeclass fromdenial.

As you can see, denial provides primitives only for rare cases of complex forms of uncertainty, which are practically never encountered in everyday programming. However, this is much more common among programmers who create their own libraries.

Install it:

pip install denialYou can also quickly try out this and other packages without having to install using instld.

This library defines an object that is proposed to be used in almost the same way as a regular None. This is how it is imported:

from denial import InnerNoneThis object is equal only to itself:

print(InnerNone == InnerNone)

#> True

print(InnerNone == False)

#> FalseThis object is also an instance of InnerNoneType class (an analog of NoneType, however, is not inherited from this), which makes it possible to check through isinstance:

from denial import InnerNoneType

print(isinstance(InnerNone, InnerNoneType))

#> TrueLike None, InnerNone (as well as all other InnerNoneType objects) always returns False when cast to bool:

print(bool(InnerNone))

#> Falseⓘ It is recommended to use the

InnerNoneobject inside libraries where a value close toNoneis required, but meaning a situation where the value is not really set, rather than set asNone. This object should be completely isolated from the user code space. None of the public methods of your library should return this object.

If None and InnerNone are not enough for you, you can create your own similar objects by instantiating InnerNoneType:

sentinel = InnerNoneType()This object will also be equal only to itself:

print(sentinel == sentinel)

#> True

print(sentinel == InnerNoneType()) # Comparison with another object of the same type

#> False

print(sentinel == InnerNone) # Also comparison with another object of the same type

#> False

print(sentinel == None) # Comparison with None

#> False

print(sentinel == 123) # Comparison with an arbitrary object

#> FalseYou can also pass an integer or a string to the class constructor. An InnerNoneType object is equal to another such object with the same argument:

print(InnerNoneType(123) == InnerNoneType(123))

#> True

print(InnerNoneType('key') == InnerNoneType('key'))

#> True

print(InnerNoneType(123) == InnerNoneType(1234))

#> False

print(InnerNoneType('key') == InnerNoneType('another key'))

#> False

print(InnerNoneType(123) == InnerNoneType())

#> False

print(InnerNoneType(123) == 123)

#> False💡 Any

InnerNoneTypeobjects can be used as keys in dictionaries.

⚠️ For most situations, I do not recommend passing arguments to the class constructor. This can lead to situations where two identifiers from different parts of your code accidentally end up being the same, which can result in errors that are difficult to catch. If you do not pass arguments, the uniqueness of eachInnerNoneTypeobject created is guaranteed.

All InnerNoneType objects have beautiful string mappings:

print(InnerNone)

#> InnerNone

print(InnerNoneType())

#> InnerNoneType(1)

print(InnerNoneType())

#> InnerNoneType(2)

print(InnerNoneType(123))

#> InnerNoneType(123, auto=False)You can also add a documentation string to the object, it will also be displayed:

print(InnerNoneType(doc='My doc string!'))

#> InnerNoneType(1, doc='My doc string!')

print(InnerNoneType(123, doc='My doc string!'))

#> InnerNoneType(123, doc='My doc string!', auto=False)Documentation strings are not taken into account when comparing InnerNoneType objects.

When used in a type hint, the expression

Noneis considered equivalent totype(None).

None is a special value for which Python type checkers make an exception, allowing it to be used as an annotation of its own type. Unfortunately, this behavior cannot be reproduced without changing the internal implementation of existing type checkers, which I would not expect until the PEP is adopted. However, there is one type checker that can work with objects from denial: simtypes. But this thing is very primitive and is only intended for runtime.

Therefore, it is suggested to use class InnerNoneType as a type annotation:

def function(default: int | InnerNoneType):

...In case you need a universal annotation for None and InnerNoneType objects, use the SentinelType annotation:

from denial import SentinelType

variable: SentinelType = InnerNone

variable: SentinelType = InnerNoneType()

variable: SentinelType = None # All 3 annotations are correct.And on the contrary, some programmers are very attentive to type safety and prefer to shift more of the work of checking types to automatic type checkers such as mypy. In such cases, it may be useful to create your own types based on InnerNoneType:

class MySentinelType(InnerNoneType):

...

def some_function(sentinel: MySentinelType):

...Using the derived class at runtime is completely identical to using the original InnerNoneType type and allows you to conveniently narrow down the scope of use of a specific type.

If you need to prevent more than one instance of your class from being created, use the singleton flag:

class MySentinelType(InnerNoneType, singleton=True):

...

sentinel = MySentinelType()

second_sentinel = MySentinelType()

#> ...

#> denial.errors.DoubleSingletonsInstantiationError: Class "MySentinelType" is marked with a flag prohibiting the creation of more than one instance.To avoid misunderstandings, if you mark a class with the singleton flag, all its descendants must also have this tag.

The problem of distinguishing types of uncertainty is often faced by programmers and they solve it in a variety of ways. This problem concerns all programming languages, because it ultimately describes our knowledge, and the questions of cognition are universal for everyone. And everyone (including me!) has their own opinions on how to solve this problem.

Current state of affairs

Some programming languages are a little better thought out in this matter than Python. For example, JavaScript explicitly distinguishes between undefined and null. I think this is due to the fact that form validation is often written in JS, and it often requires such a distinction. However, this approach is not completely universal, since in the general case the number of layers of uncertainty is infinite, and here there are only 2 of them. In contrast, denial provides both features: the basic InnerNone constant for simple cases and the ability to create an unlimited number of InnerNoneType instances for complex ones. Other languages, such as AppleScript and SQL, also distinguish several different types of undefined values. A separate category includes the languages like Rust, Haskell, OCaml, and Swift, which use algebraic data types.

The Python standard library uses at least 15 sentinel objects:

- _collections_abc: marker

- cgitb.UNDEF

- configparser: _UNSET

- dataclasses: _HAS_DEFAULT_FACTORY, MISSING, KW_ONLY

- datetime.timezone._Omitted

- fnmatch.translate() STAR

- functools.lru_cache.sentinel (each @lru_cache creates its own sentinel object)

- functools._NOT_FOUND

- heapq: temporary sentinel in nsmallest() and nlargest()

- inspect._sentinel

- inspect._signature_fromstr() invalid

- plistlib._undefined

- runpy._ModifiedArgv0._sentinel

- sched: _sentinel

- traceback: _sentinel

Since the language itself does not regulate this in any way, there is chaos and code duplication. Before creating this library, I used one of them, but later realized that importing a module that I don't need for anything other than sentinel is a bad idea.

Not only did I come to this conclusion, the community also tried to standardize it. A standard for sentinels was proposed in PEP-661, but at the time of writing it has still not been adopted, as there is no consensus on a number of important issues. This topic was also indirectly raised in PEP-484, as well as in PEP-695 and in PEP-696. Unfortunately, while there is no "official" solution, everyone is still forced to reinvent the wheel on their own. Some, such as Pydantic, are proactive, as if PEP-661 has already been adopted. Personally, I don't like the solution proposed in PEP-661, mainly because of the implementation examples that suggest using a global registry of all created sentinels, which can lead to memory leaks and concurrency limitations.

In addition to denial, there are many packages with sentinels in Pypi. For example, there is the sentinel library, but its API seemed to me overcomplicated for such a simple task. The sentinels package is quite simple, but in its internal implementation it also relies on the global registry and contains some other code defects. The sentinel-value package is very similar to denial, but I did not see the possibility of autogenerating sentinel ids there. Of course, there are other packages that I haven't reviewed here.

And of course, there are still different ways to implement primitive sentinels in your code in a few lines of code without using third-party packages.

Q1: Is this library the best option for sentinels?

A: Sentinel seems like a very simple task conceptually, we just need more None's. But suddenly, creating a good sentinel option is one of the most difficult issues. There are too many ways to do this and too many trade-offs in which you need to choose a side. The design of sentinel objects is similar to the creation of axioms: it delves deep into parts of our psyche that are not usually subject to critical analysis, and therefore it is very difficult to talk about the problems that arise. So I'm not claiming to be the best solution to this issue, but I've tried to eliminate all the obvious disadvantages that don't involve trading. I'm not sure if it's even possible to find the best solution in this area, so all I can do is make an arbitrary decision and stick to it. If you want, join me.

Q2: Why is the uniqueness of the values not ensured? The None object is a singleton. In Python, it is impossible to access the None name and get a different value. But in denial, it is possible for a user to create two different objects by passing two identical IDs there. In rare cases, this can lead to unintended errors, for example, if the same identifier is accidentally used in two different places in the program. Why is that?

A: To ensure that a certain value is used in the program only once, there are 2 possible ways: 1. create a registry of all such values and check each new value for uniqueness in runtime; 2. check the source code statically, for example using a special linter. I found the second option too difficult for now, so the first one remains. The main problem is the possibility of memory leaks. There is a good general rule for programming: rely as little as possible on global state, because it can create unexpected side effects. For example, if you create unique identifiers in a loop, the registry may overflow. Would you say that no one will create them in a loop? Well, I'm not ready to take any chances. It also creates problems with concurrency. The fact is that checking the value in the registry and entering it into the registry are two independent operations that take some time between them, which means that errors are possible due to the race condition. If you protect this operation with a mutex, it will increase the percentage of sequential execution time in the program, which means it will slow down the entire program due to Amdahl's law. Because I can imagine situations where creating sentinels would be a fairly frequent operation and it would create performance problems (it's time to make fun of Python's performance because of the GIL, but I hope for a better future). Current compromise: always use InnerNoneType without arguments, unless you have a serious reason to do otherwise. In this case, the uniqueness of each object is guaranteed, since "under the hood", each time a new object is created, an internal counter is incremented (thread-safe!), which then checks the uniqueness of the object.

Q3: What could be the reasons to use InnerNoneType with arguments? It always seems like a bad idea. How about removing this feature altogether?

A: This is almost always a bad idea. But in some extremely rare cases, it can be useful. It may be that two sections of code that do not know about each other will want to transfer a compatible sentinel to each other. It is even possible that it will be transmitted over the network and "recreated" on the other side. It is for such cases that the option to use your own identifiers has been left. But it's better to use empty brackets.

Q4: Why not use a separate class with singleton objects for each situation when we need a sentinel? Then it will be possible to make checks through isinstance, and it will also be possible to write more accurate type hints.

A: The ability to use classes as type hints is a compelling argument. It would be possible to create several classes in different parts of the program, assigning different semantics to each of them, and then checking compliance using a type checker such as mypy. However, I did not make this a basic mechanism for denial, as I believe that in most cases the semantics will not actually differ. At the same time, creating a new class each time is more verbose than creating objects. However, I left the option to inherit from InnerNoneType if you still consider it necessary in your code. Objects of inheriting classes (if you do not override the behavior of the class in any way) will behave the same as InnerNoneType objects. But they will not be singletons, which allows you to group several different objects with the same semantics within a single class.

Q5: You're using only one InnerNoneType class, but the internal id that makes objects unique can be either generated automatically or passed by the user. Doesn't this mean that it would be worthwhile to allocate 2 independent classes?

A: I did this to reduce cognitive load. I haven't seen any cases where a clear division into two classes provides a practical (rather than aesthetic) benefit, while you don't have to think about which class to import and how its use differs.

Q6: Why is InnerNoneType not inherited from NoneType?

A: The purpose of these classes is really quite similar. However, I felt that inheriting from NoneType could lead to breakdowns in the old code, which might expect that only one instance of NoneType is possible, and therefore uses the isinstance check as an analogue of the is None check. However, I cannot give figures on how often such constructions occur in existing code. Perhaps you should collect such statistics using the GitHub API.

Q7: How is the uniqueness of InnerNoneType objects ensured?

A: If you create InnerNoneType objects without passing any arguments to the constructor, an id that is unique within the process is created inside each object when it is created. It is by this id that the object will check whether it is equal to another InnerNoneType object. It will be equal to another object only if it has the same id inside it, which is usually impossible, and therefore the object remains equal only to itself. If you passed your own id when creating the object, the automatic id is not created, yours is used. In this case, it is your job to track possible unwanted intersections. The library can also distinguish between objects where the id is created automatically and where it is passed from outside, using a special flag inside each value. This guarantees that there are no intersections between automatically generated and non-automatically generated ids.

Q8: Why all these complications and an additional library for sentinels? I just write sentinel = object() in my code and then do checks like x is sentinel. It works, but you've overcomplicated things.

A: Indeed, we already have one source of unique ids for objects: their addresses in memory. Checks like x is sentinel can be identical in meaning to those used in this library. However, this option has two significant drawbacks. First, you lose the compactness of string representation that denial provides. Second, this method does not allow you to create two identical sentinel objects if you want to, which prevents you from, for example, transferring sentinel objects over the network or between processes. Unfortunately, this is impossible with memory addresses. Since this library is positioned as universal, I had to abandon this option.

Q9: Why don't we use Enums as sentinels? It's already in the standard library, no need to invent anything. And it can do all the things we expect from sentinels.

A: Various people have suggested this method to me, and it was also mentioned in PEP-661. The PEP argues that Enum's __repr__ is too long. In denial, I made a short and informative __repr__, which should be sufficient in principle. However, here are some other reasons not to use Enum: 1. Denial can be used in recursive algorithms where the number of nesting levels is unknown in advance. This is possible because the number of variables with sentinels is not limited here. In the case of Enum, you must know the number of nesting levels in advance. 2. Using a single Enum class with all sentinels in the program contradicts the idea of modularity. In essence, this is equivalent to using global variables, which usually indicates code with a “bad smell.” If you create an Enum class for each sentinel, it will look too verbose. 3. Under the hood, Enum uses the global registry approach that I discussed in the FAQ section of the README. 4. Enum usually has slightly different semantics. For example, I can hardly imagine a situation where I would want to iterate through all sentinels. 5. Enum is generally too complex a tool for such a simple purpose. In my opinion, the entire Enum module should have been deprecated long ago. The sheer size of the module's documentation and the existence of several official manuals for it suggest that something is wrong here. 6. Another argument may seem ridiculous given the slowness of CPython, but I'll mention it anyway. Enum forces the user to use values via a dot, such as EnumClass.SENTINEL. This leads to an unnecessary lookup operation and a slight slowdown of the program. However, I haven't done any measurements, so perhaps this has been optimized in some way by the CPython developers.

Q10: Why does the singleton flag prohibit the creation of a second class object if you can simply return the same object?

A: There are different possible implementations of the Singleton pattern. In Python code, you often see implementations that “hide” the uniqueness check of an instance under the hood and simply return the first instance when you try to create a second one. But in my opinion, this implementation of the pattern is flawed because it hides the true nature of objects from the reader, which violates the Zen of Python ("explicit is better than implicit"). The code implicitly propagates attempts to create multiple objects of the same class, when in fact only one object is needed. In my opinion, if we want an object to have only one instance, we should explicitly prohibit the creation of more than one instance. In this case, there will be no more than one instance of the class in the code, which makes the code base more consistent and transparent.