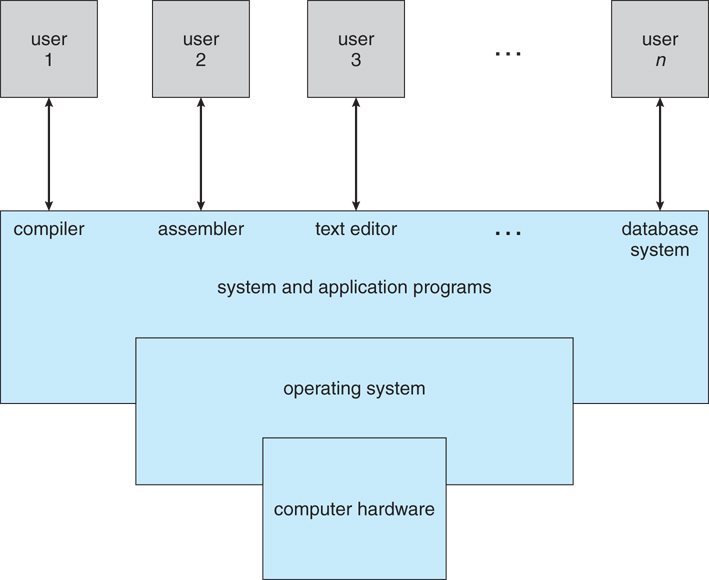

The computer system can be divided into four components:

-

Hardware – provides basic computing resources like CPU, memory, I/O devices.

-

Operating system- Controls and coordinates use of the hardware among various applications and users.

-

Application programs – These are programs that carry out a specific task other than one relating to the operation of the computer itself. For example Word processors, compilers, web browsers, database systems, video games

-

Users - People, machines, other computers.

The operating system serves as an interface between hardware and ( Apps & Users ). It provides services for Apps & Users. It is also responsible for managing the computer system's hardware and software resources.

Figure: A view of all components of a computer system.

The OS provides services that are helpful to the user are

-

User interface (CUI/shell and GUI): Users can issue commands to the computer system using a command-line interface(CLI), a Graphical User Interface(GUI ), or a batch command system.

-

Program execution: The OS should be able to load a program into the main memory(RAM), run and terminate the program, either normally or abnormally.

-

I/O operation: The Operating System is responsible for the transfer of data to and from I/O devices(keyboards, terminals, printers, and storage devices).

-

File system manipulation: - The Operating System also maintains directory and subdirectory structures.

-

Communication: The OS also provides means for Inter-process communications(IPC) between processes.

-

Error detection: Both hardware and software errors must be detected and handled appropriately, with minimal harmful repercussions.

OS services that are helpful to the system-

-

Resource allocation: When multiple users or multiple jobs are running simultaneously, resources need to be allocated to each of them. The operating system manages many different types of resources.

-

Accounting: The OS helps keep track of system activity and resource usage.

-

Protection and Security: The OS help prevents harm to the system and resources. The harm can come through wayward internal processes or malicious outsiders. Authentication, ownership, and restricted access are prominent parts of this sy

The kernel is that part of the operating system responsible for interacting with the hardware directly.

A shell, also referred to as a command interpreter, is that part of the operating system that receives commands from the users.

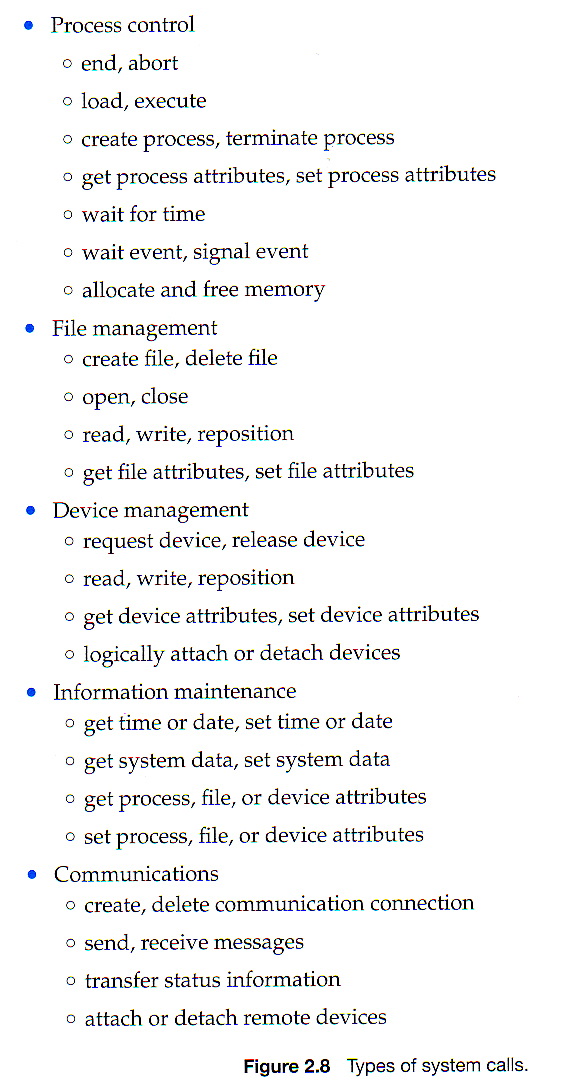

A system call provides means for an application program to request a service from the kernel for which it does not have permission.

Application programs usually do not have permission to perform operations like accessing I/O devices and communicating with other programs. System calls are generally written in C or C++, although some are written in assembly for optimal performance.

System calls are of six major categories as given in the following figure.

SIGHUP ("signal hang up") is a signal sent to a process when its controlling terminal is closed. (It was originally designed to notify the process of a serial line drop.)HUP signals are sometimes generated by the terminal driver in an attempt to “clean up” (i.e., kill) the processes attached to a particular terminal.

The SIGTERM signal is also called a standard kill. Whenever kill is executed without specifying the signal, a kill -15 is assumed.

The SIGKILL is different from most other signals in that it is not being sent to the process, but to the Linux kernel. A kill -9 is also called a sure kill. The kernel will shoot down the process.

A running process can be suspended when it receives a SIGSTOP signal. This is the same as kill -19 on Linux.

A suspended process does not use any cpu cycles, but it stays in memory and can be reanimated with a SIGCONT signal (kill -18 on Linux).

Some processes can be suspended with the Ctrl-Z key combination. This sends a SIGSTOP signal to the Linux kernel, effectively freezing the operation of the process. When doing this in vi(m), then vi(m) goes to the background. The background vi(m) can be seen with the jobs command.

Running the fg command will bring a background job to the foreground. The number of the background job to bring forward is the parameter of fg.

Jobs that are suspended in background can be started in background with bg. The bg will send a SIGCONT signal.

That will suspend execution of the process. It won't immediately free the memory used by it, but as memory is required for other processes the memory used by the stopped process will be gradually swapped out.

SIGNAL INTERNALS

A signal is generated either by the kernel internally (for example, SIGSEGV when an invalid address is accessed, or SIGQUIT when you hit Ctrl+), or by a program using the kill syscall (or several related ones).

The CPU, based on a special register value, has an address in memory where it expects to find an "interrupt descriptor table" which is actually a vector table. There is one vector for every possible exception, like division by zero, or trap, like INT 3 (debug). When the CPU encounters the exception it saves the flags and the current instruction pointer on the stack and then jumps to the address specified by the relevant vector. In Linux this vector always points into the kernel, where there is an exception handler. The CPU is now done, and the Linux kernel takes over.

Note, that you can also trigger an exception from software. For example, the user presses CTRL-C, then this call goes to the kernel which calls its own exception handler. In general, there are different ways to get to the handler, but regardless the same basic thing happens: the context gets saved on the stack and the kernel's exception handler is jumped to.

The exception handler then decides what thread should receive the signal

To send the signal what the kernel does is first set a value indicating the type of signal, SIGHUP or whatever. This is just an integer. Every process has a "pending signal" memory area where this value is stored. Then the kernel creates a data structure with the signal information. This structure includes a signal "disposition" which may be default, ignore or handle. The kernel then calls its own function do_signal() . The next phase begins.

do_signal()first decides whether itwill handle the signal. For example, if it is a kill , then do_signal()just kills the process, end of story. Otherwise, it looks at the disposition. If the disposition is default, then do_signal()handles the signal according to a default policy that depends on the signal. If the disposition is handle, then it means there is a function in the user program which is designed to handle the signal in question and the pointer to this function will be in the aforementioned data structure. In this case do_signal() calls another kernel function, handle_signal() , which then goes through the process of switching back to user mode and calling this function. The details of this handoff are extremely complex. This code in your program is usually linked automatically into your program when you use the functions in signal.h

An interrupt is a signal triggered by hardware or software when an event or a process needs urgent attention. The interrupt requires interruption of the current working process for a higher priority process.

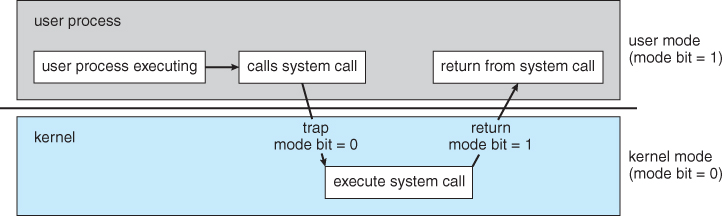

To ensure the proper functioning of the OS, we should be able to distinguish between the execution of operating-system code and user program code. Two separate modes of operation called user mode and kernel mode are used. The system is in user mode when executing harmless code in user applications. The system is in kernel mode (also known as system mode, supervisor mode, privileged mode) when executing potentially dangerous code in the system kernel.

Certain privileged instructions can only be executed in kernel mode. Kernel-mode can be entered by making system calls. A bit, called the mode bit is added to the hardware of the computer to indicate the current mode: kernel (0) or user (1). No user code can flip the mode bit.

Figure: User mode and Kernel-mode transition

Booting is the process of starting the computer and loading the kernel. When a computer is turned on, the power-on-self-test (POST) is performed. Then the bootstrap loader, which resides in the ROM, is executed. The bootstrap loader loads the kernel or a more sophisticated loader.

Batch-processing Operating System: It takes jobs with similar requirements and groups them into batches. It is the responsibility of the operator to sort jobs with similar needs.

Single-processing Operating System: It executes a single process at a given time.

Multi-programming Operating System: It increases CPU utilization as it keeps multiple jobs in the memory so that the CPU always has one job to execute.

Multi-tasking Operating System: It is an extension of multiprogramming where the CPU executes multiple tasks by switching among them.

A process is an instance of a program in execution.

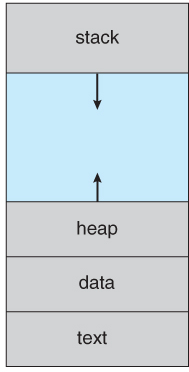

As depicted in the following diagram, process memory is divided into four sections:

Text section: contains the compiled program code, read in from secondary storage as the program is loaded.

Data section: is responsible for storing global and static variables.

Heap Section: is necessary for dynamic memory allocation, and is managed via calls to new, delete, malloc, free, etc.

Stack space: is used for local variables. Memory space on the stack is reserved for local variables as they are declared, and the space gets freed up as the variables go out of scope. The stack space is also used for function return values.

The heap and the stack start at opposite ends of the process's free memory space and start growing towards each other. If they should ever collide, it either gives rise to a stack overflow error, or an invocation of new or malloc() will fail because of insufficient memory.

In case processes are swapped out of memory and swapped back in later, vital information such as the program counter and the value of all program registers must also be stored and restored.

Figure: Process space

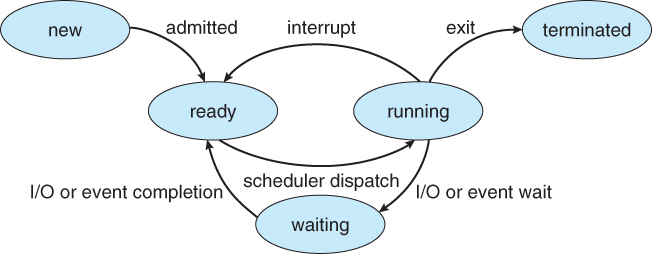

Processes can be in one of 5 states. The states of a process are as follows:

New - The state of a process during its creation.

Ready - The state of a process where all its required resources are available, but the CPU is not currently executing the process.

Running - The state of a process during its execution.

Waiting - The state of a process when it cannot be executed, as it is waiting for some resource or some event.

Terminated - The process execution is complete.

Some systems may have other states besides the ones listed here.

A Process Control Block(PCB) stores the following process-specific information for each process.

Process State: As discussed above, the state may be new, ready, running, etc.

Process ID: and parent process ID.

CPU registers and Program Counter - This information needs to be saved and restored in case swapping occurs.

CPU-Scheduling information - Such as priority information and pointers to scheduling queues.

Memory-Management information - page tables or segment tables.

Accounting information - user and kernel CPU time consumed, account numbers, limits, etc.

I/O Status information - Information such as Devices allocated, open file tables.

There are two primary objectives of the process scheduling system. Firstly, to keep the CPU busy always. Secondly, to deliver fast response times for all programs, especially interactive ones.

The process scheduler implements suitable policies for swapping processes in and out of the CPU to meet these objectives. The two objectives can be conflicting; every time swapping occurs, the CPU takes time to do so, thereby losing time from doing productive work.

The PCBs are maintained in scheduling queues by the Operating System. The OS maintains a separate queue for each of the process states and PCBs of all processes in the same execution state are placed in the same queue. When the process makes a transition to a different state, its Process Control Block is removed from its current queue and moved to its new state queue.

The OS maintains the following scheduling queues.

Ready queue − All processes in the ready state are placed in this queue.

Device queues − The processes waiting due to the unavailability of a device are placed in this queue.

Other scheduling queues may also be created and used if necessary.

There are three types of process schedulers. A process transitions among the various scheduling queues during its lifecycle. The OS selects processes from the queues based on specific criteria. The selection is done by the appropriate scheduler. Other scheduling queues may also be created and used if necessary.

It is responsible for bringing new processes to the ready state. It controls the degree of multiprogramming, i.e., the number of processes present in ready state at any time. It is vital that the long-term scheduler carefully select both IO and CPU-bound processes. IO-bound tasks use much of their time in input and output operations, while CPU-bound processes spend their time on CPU. The job scheduler increases efficiency by maintaining a balance between the two. The long-term scheduler runs less frequently, such as when one process is terminated, it selects one more process to be loaded in its place. Hence, it can afford to take the time to implement intelligent and advanced scheduling algorithms.

It is responsible for selecting one of the processes in the ready state and allocating it to the CPU. The short-term scheduler is invoked very frequently, on the order of 100 milliseconds, and must very quickly swap one process out of the CPU and swap in another one.

It is responsible for swapping out one or more processes from the ready queue for a short time to allow smaller, faster jobs to finish up quickly and clear the systems; when system loads get high.

A scheduling system must select a good process mix of CPU-bound processes and I/O bound processes to be efficient.

In case of an interrupt, the CPU must save the state of the currently executing process, then goes into kernel mode to handle the interrupt, and finally restore the state of the interrupted process.

Likewise, a context switch occurs when the time slice for one process has expired, and a different ready process needs to be loaded. Instigated by a timer interrupt, the context switch will save the current process's state(registers, program counter, PCB) and restore the new process's state.

Context switches need to be extremely fast to save CPU time as they occur ty occur very frequently.

Operations on Processes Process Creation One process creating another process through appropriate system calls, such as fork or spawn, is called process creation. The processes are called parent process and child process, respectively. Each process has a unique integer identifier known as process identifier or PID. A process may obtain resources either from its parent or from the operating system directly. A parent process may continue executing with its children processes or may wait for them to complete. A process may be a duplicate of its parent process (same code and data) or may have a new program loaded into it.

Parent Process In a UNIX system, every process(except the very first one) is created when a process creates a new process.

Those 2 processes establish a relationship where:

parent process: is the process creating the new process

child process: is the newly-created process.

Every process (except the very first one):

has one parent process, and

can have many child processes.

A child is a process created by another(parent) process. A child process inherits most attributes, such as open files, from its parent process. In UNIX, a child process is created as a copy of the parent using the fork system call. The purpose of fork() is to create a new process, which becomes the child process of the caller. Using the exec system call, the child process can later overlay itself with another program as needed.

A running process whose parent process has already been terminated or finished is called orphan process. In a UNIX system, any orphaned process is immediately adopted by the init system process. This operation is called re-parenting, which occurs automatically. Even though technically, the orphan process has the init process as its parent, it is still called an orphan process since the process that created it no longer exists.

A process may be orphaned unintentionally or intentionally.

Unintentional Orphan: They occur when the parent process terminates or crashes. The process group mechanism in most Unix-like operation systems can be used to help protect against accidental orphaning.

Intentional Orphan: They get detached from the user’s session and are left running in the background. The purpose of these orphans is to allow a long-running job to complete without further user attention or to start an indefinitely running service.

A daemon process is an intentionally orphaned process to have run a background process. It is usually created by a process forking a child process and then immediately exiting, thus causing init to adopt the child process. In a Unix environment, the parent process of a daemon is often, but not always, the init process.

It is long-lived. A daemon process is often started at system boot and remains in existence until the system is shut down. It runs in the background, and has no controlling terminal from which it can read input or to which it can write output,examples(syslogd,httpd)

A process that has completed execution but hasn’t been reaped by its parent process. As a result, it holds a process entry and the PID in the process table.

Unlike normal processes, a zombie process is not affected by the kill command.

When a process ends, the memory and resources held by it are deallocated and freed up. However, the corresponding entry in the process table still exists. The parent may read the child’s exit status using the wait system call, on which the zombie gets removed.

After the removal of the zombie, the process identifier (PID) and entry in the process table can be reused.

A zombie process is similar to a memory leak, i.e. a loss of a system resource caused by failure to release a previously reserved portion. A zombie process is usually a sign of invalid software behavior. Zombie process cannot be killed by SIGKILL .This ensures that the parent can always eventually perform a wait().

A child process after completion enters the ZOMBIE state temporarily; it remains in that state until the parent executes a wait() … it then terminates. However, if the parent terminates before issuing a wait(), the ZOMBIE process will become an ORPHAN process. Typically, in Linux the init process is entrusted with the responsibility to handle such orphan processes; it is made the parent of such processes, and init issues the wait() call periodically.

A common way of reaping dead child processes is to establish a handler for the SIGCHLD signal. This signal is delivered to a parent process whenever one of its children terminates, and optionally when a child is stopped by a signal. Alternatively, but somewhat less portably, a process may elect to set the disposition of SIGCHLD to SIG_IGN, in which case the status of terminated children is immediately discarded (and thus can’t later be retrieved by the parent), and the children don’t become zombies

The act of deletion of the PCB of the process refers to as process termination.

A parent process can terminate a child process in the following cases:

If a child process has exceeded its resource usage.

If a child process's result is no longer required.

If the parent process needs to terminate and the operating system does not permit an orphan process.

The kernel is typically the first process that gets created. It is the ancestor of all other processes and is placed at the root of the process tree.

Processes can be classified as follows:

Independent Processes operating concurrently on a system can neither affect other processes nor be affected by other processes.

Cooperating Processes They, on the other hand, may affect or may be affected by other processes.

The usefulness of cooperating processes is as follows:

Information Sharing - There can be many processes that need access to the same file.

Computation speedup - A problem can often be solved faster if broken down into sub-tasks to be solved simultaneously.

Modularity - Breaking a system down into cooperating modules to create an efficient architecture.

Convenience - To enable multi-tasking even in single-users, such as editing, compiling, printing, and running the same code in different windows.

Cooperating processes require some means of inter-process communication, which is most commonly one of two types:

Shared memory This is faster once it is set up, as no system calls are needed, and access takes place at normal memory access speeds. However, the setup is more complicated and does not work well across multiple computer systems. Shared Memory is usually preferred when a large quantity of information needs to be shared fast on the same computer system.

Message Passing This requires system calls for every message transfer and is slower in comparison, but the setup is much simpler, and it works well across multiple computer systems. Message passing is usually preferred when the amount or frequency of data transfers is small, or multiple computers are involved.

A thread is the smallest set of instructions that a scheduler can manage independently. A thread is a unit of CPU utilization, consisting of a program counter, a stack, a set of registers, and a thread ID.

There can be multiple threads within the same process, executing concurrently and sharing resources such as memory. The threads of a process share its instructions and its context.

Difference between process and thread –

Processes are typically independent while threads exist as parts of a process

Processes contain much more state information than threads.

Processes have separate address spaces, whereas threads share their address space

Processes interact only through system-provided inter-process communication mechanisms

Context switching between threads in the same process is typically faster than context switching between processes

Advantages of multi-threaded programming –

Responsiveness

Faster execution

Better resource utilization

Easy communication

Parallelization

Almost every process has alternating cycles of CPU burst times and waiting for I/O. In a simple system, where a single process is running, CPU cycles are lost when the process is waiting for I/O.

CPU scheduling enables one process to utilize the CPU while another process is waiting for I/O, thereby preventing the loss of CPU cycles. The aim is to make the overall system as efficient and fair as possible, subject to varying and often dynamic conditions.

In case the CPU is idle, the CPU Scheduler (short-term scheduler) selects a process from the ready queue to run next.

CPU scheduling decisions need to take place under one of the following conditions:

-

A process goes from the running state to the waiting state, such as for an I/O request or invocation of the wait( ) system call.

-

A process goes from the running state to the ready state, for example, in response to an interrupt.

-

A process switches from the waiting state to the ready state, say at the completion of I/O or a return from wait( ).

-

A process terminates.

CPU scheduling is optional for the second and third conditions but necessary in the other two conditions.

In non-preemptive scheduling or cooperating scheduling, a process keeps hold of the CPU until it terminates or switches to the waiting state. Some machines support only non-preemptive scheduling. For example, Window 3.1x.

In preemptive scheduling, a process can be made to relinquish the CPU and switch to the ready queue. For example., Unix, Linux, Windows 95, and higher.

The dispatcher is responsible for giving control of the CPU to the process selected by the scheduler. This function involves

Context switching.

Going to user mode.

Starting the newly loaded process from the correct instruction.

The dispatcher must be very fast, as it is run on every context switch. The overhead of the dispatcher is referred to as dispatch latency.

There are certain criteria to be taken into consideration while selecting the appropriate scheduling algorithm for a particular scenario:

CPU utilization - Ideally, the CPU should be busy 100% of the time to prevent wastage of CPU cycles. In reality, CPU utilization should be as high as possible(typically ranges from 40% to 90%).

Throughput - The number of processes completed per unit of time.

Turnaround time - The time required for a particular process to complete, from arrival time to completion time.

Waiting time - The time processes are in the ready scheduling queue, waiting for their turn to get CPU.

Response time -The time taken for an interactive program to issue a command till getting a response for that command.

In general, the aim should be to optimize the averages of the mentioned criteria ( to maximize CPU utilization and throughput, and minimize turnaround time, waiting time, and response time.

There are several CPU scheduling algorithms.

First-Come First-Serve Scheduling (FCFS) FCFS is a very straightforward algorithm. It follows a FIFO queue, like customers waiting in a line at the store.

However, FCFS can lead to long average wait times, especially if the first arriving process has a long burst time.

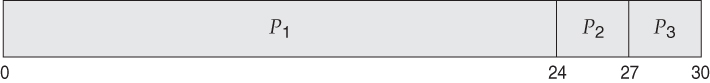

Let’s consider the following example to demonstrate this algorithm

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 24 |

| P2 | 3 |

| P3 | 3 |

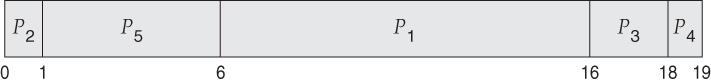

In the above Gantt chart, process P1 is the first one to arrive. Hence the average waiting time is ( 0+ 24+ 27 )/ 3 = 17.0 ms for all three processes.

However, in the second Gantt chart, P1 is the last to arrive. Hence the processes have an average wait time of ( 0 + 3 + 6 ) / 3 = 3.0 ms, as two of the three finish much quicker, and the other process is only delayed by a short amount.

FCFS may also lead to blockage of the system, which is known as the convoy effect. In case a process that is CPU intensive blocks the CPU, other I/O intensive processes get queued after it, leaving the I/O devices idle. After the first process finally lets go of the CPU, the I/O processes go through the CPU quickly, leaving the CPU idle while all the processes queue up for I/O, and then the cycle repeats itself.

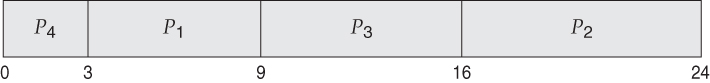

SJF scheduling algorithm suggests scheduling the shortest job(based on CPU burst time) first, then selecting the next shortest job to be scheduled next.

The Gantt chart below demonstrates the SJF algorithm based on the following CPU burst times (assume that all processes arrive simultaneously).

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 6 |

| P2 | 8 |

| P3 | 7 |

| P4 | 3 |

In this case the average wait time is ( 0 + 3 + 9 + 16 ) / 4 = 7.0 ms. If FCFS had been used then the average wait time would have been 10.25 ms for the same processes.

SJF can theoretically be proven as the fastest scheduling algorithm however, the problem is that the CPU burst times for the processes are not known in advance.

A practical approach is to predict the duration of the next CPU burst time based on historical data of recent CPU burst times for the process. One excellent method is the exponential average, which is defined as follows.

estimate[ i + 1 ] = alpha * burst[ i ] + ( 1.0 - alpha ) * estimate[ i ]

Here, the previous estimate contains the history of all last CPU burst times, and alpha is the weight factor for the relative importance of recent data versus past data. If alpha is 1.0, then the historical data is ignored, and we assume the next burst will be the same duration as the last burst. If alpha is 0.0, all measured burst times are ignored, and the burst time becomes constant. It is common practice to set alpha at 0.5.

SJF can be either preemptive or non-preemptive.

Preemption in SJF can occur when a new process enters the ready queue with a predicted burst time shorter than the remaining burst time of the process currently on the CPU. Preemptive SJF is referred to as the shortest remaining time first scheduling algorithm.

The following Gantt chart demonstrates the SRTF algorithm.

| Process | Burst Time | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10 | 3 |

| P2 | 1 | 1 |

| P3 | 2 | 4 |

| P4 | 1 | 5 |

| P5 | 5 | 2 |

The average wait time is ( ( 5 - 3 ) + ( 10 - 1 ) + ( 17 - 2 ) ) / 4 = 26 / 4 = 6.5 ms. Average wait times for the same setup are 7.75 ms for non-preemptive SJF or 8.75 for FCFS respectively.

Priority scheduling is a generic case of SJF, where each process is assigned a priority, and the process with the highest priority gets scheduled first.

On the other hand, SJF uses the inverse of the next expected CPU burst time as its priority.

Priorities are implemented using integers within a fixed range. Lower integers indicate higher priorities, with 0 being the highest possible priority.

The following Gantt chart demonstrates the Priority scheduling algorithm.

| Process | Burst Time | Priority |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | 10 | 3 |

| P2 | 1 | 1 |

| P3 | 2 | 4 |

| P4 | 1 | 5 |

| P5 | 5 | 2 |

The average waiting time for this setup using Priority scheduling is 8.2 ms. Priority scheduling may be preemptive or non-preemptive.

Priority scheduling has a significant drawback called indefinite blocking, or starvation, where a low-priority process waits indefinitely because there are always other processes ready that have higher priority.

The remedy to the starvation problem is aging, where priorities of processes increase the longer they wait. Under this scheme, a low-priority job will eventually raise its priority high enough to get run.

Round-robin scheduling has a similarity to the FCFS scheduling, except that CPU bursts are limited based on a parameter called time quantum.

When a process is allocated to the CPU, a timer is set according to the time quantum. In case the process finishes its CPU burst before the time quantum timer expires, then it is swapped out of the CPU, similar to the standard FCFS algorithm.

If the timer expires first, the process is swapped out of the CPU and transferred back end of the ready scheduling queue. The ready queue acts as a circular queue.

RR scheduling can give the illusion that all processors share the CPU equally. However, the average wait time may be longer than other CPU scheduling algorithms.

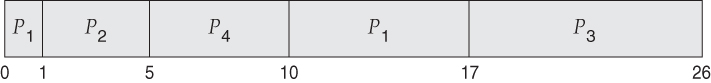

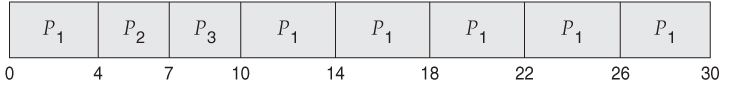

The following example demonstrates the RR algorithm. The time quantum value is set as 4.

| Process | Burst Time |

|---|---|

| P1 | 24 |

| P2 | 3 |

| P3 | 3 |

The average wait time, in this case, is 5.66 ms. The performance of the Round-robin algorithm depends on the value of the time quantum selected. If the quantum is very large, the RR algorithm is the same as the FCFS algorithm.

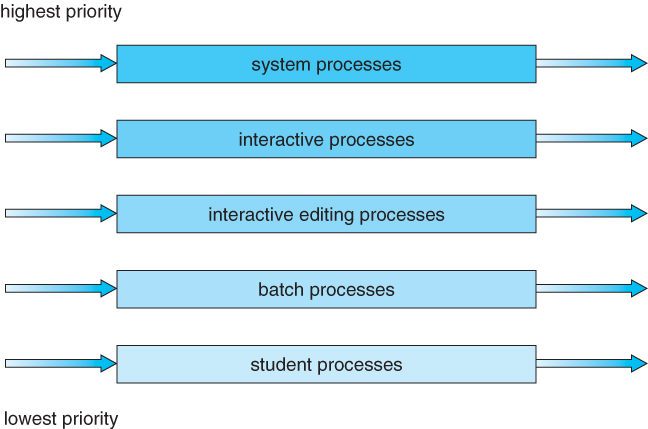

Here, processes are strictly categorized and placed at multiple separate queues, each following an appropriate scheduling algorithm with different parametric adjustments. In this algorithm, processes cannot switch between queues till they finish.

There needs to be scheduling between the queues also. Two popular strategies are strict priority (no process in a lower priority queue runs until all higher priority queues are empty) and round-robin (each queue gets a time slice in turn, possibly of different sizes).

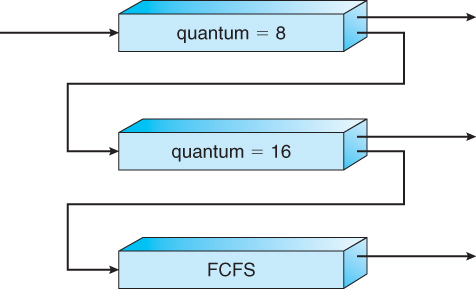

Multilevel feedback queue scheduling is the same as standard multilevel queue scheduling described above, except processes may be switched between queues for certain reasons:

If the characteristics of a process change between CPU-intensive and I/O intensive.

Aging may also be considered so that a process waiting for some time can be moved up into a higher priority queue.

Multilevel feedback queue scheduling is extremely flexible, but it is also the most complicated to implement because of all the adjustable parameters. Some of the parameters which define this type of system include the following.

The total number of queues.

The scheduling algorithm being used in each respective queue.

The strategies deciding whether to promote or demote processes from one queue to another.

The strategy to decide which queue a process enters initially.