-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 3

Decimals 64

Authors include Carl Sassenrath, John Niclasen, Ladislav Mecir

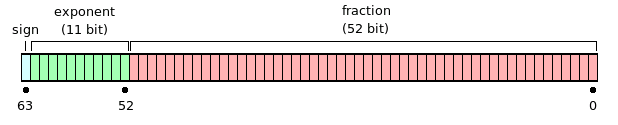

Rebol decimals are standard 64-bit IEEE 754 binary floating point numbers.

The bits in a Rebol decimal are laid out like this:

A number has value v:

v = s × 2e × m

Where

s = +1 when the sign bit is 0 (positive numbers and positive zero)

s = −1 when the sign bit is 1 (negative numbers and negative zero)

e = exponent − 1023 (in other words the exponent is stored as "biased with 1023"), if the exponent is greater than zero

e = −1022, if the exponent is zero (denormalized numbers)

m = 1.fraction in binary (that is, the significand is the binary number 1 followed by the radix point followed by the binary bits of the fraction), if the exponent is greater than zero. In this case 1 ≤ m < 2.

m = 0.fraction in binary (that is, the significand is the binary number 0 followed by the radix point followed by the binary bits of the fraction), if the exponent is zero (denormalized numbers). In this case 0 ≤ m < 1.

The first bit is the sign bit.

Positive zero looks like this: #{0000 0000 0000 0000}

Negative zero looks like this: #{8000 0000 0000 0000}

The next 11 bits are the exponent. That gives 0 ≤ exponent < 211 − 1 = 2047. The exponent value 2047 is reserved for overflow and NaN (Not a Number) and the exponent value 0 is reserved for denormalized numbers. Therefore the above e, obtained by subtracting the bias 1023 from the exponent, can range from −1022 to 1023.

Numbers with exponents other than zero are said to be normalized. They preserve the full precision of the fraction, so they have 53 significant bits (including the 1 before the radix point in the calculation of m above).

Numbers with zero in the exponent are said to be denormalized and have from 1 to 52 significant bits.

Positive normalized numbers with fraction bits set to zero are in the range: #{0010 0000 0000 0000} - #{7FE0 0000 0000 0000}

That is 2046 different exponents for positive normalized numbers.

Positive denormalized numbers have exponent zero and e equal to −1022.

Negative normalized numbers with fraction bits set to zero are in the range: #{8010 0000 0000 0000} - #{FFE0 0000 0000 0000}

That is 2046 different exponents for negative normalized numbers.

Negative denormalized numbers have exponent zero and e equal to −1022.

The remaining 52 bits are the fraction used in the calculation of v (see above). That gives 252 = 4'503'599'627'370'496 different fractions.

(The next 2 numbers are denormalized, because the exponent is zero.)

Positive number with exponent bits set to zero and all fraction bits set: #{000F FFFF FFFF FFFF}

Negative number with exponent bits set to zero and all fraction bits set: #{800F FFFF FFFF FFFF}

If the fraction bits are all zero and the exponent is positive, the number is a power of 2. Because 1023 is subtracted from the exponent, the number 2.0 is: #{4000 0000 0000 0000}

The exponent is #400 = 1024 and 1024 − 1023 = 1. So we can calculate the number v = +1 × 21 × 1.0 = 2.0

Other powers of 2:

#{4010 0000 0000 0000} = 4.0

#{4020 0000 0000 0000} = 8.0

#{4030 0000 0000 0000} = 16.0

etc.

#{3FF0 0000 0000 0000} = 1.0

#{3FE0 0000 0000 0000} = 0.5

#{3FD0 0000 0000 0000} = 0.25

etc.

See the range table.

The set of real numbers is infinite, while the set of 64-bit IEEE 754 numbers is finite (there are at most 2 ** 64 64-bit numbers). Therefore, the relation between real numbers and IEEE 754 numbers cannot be symmetric. In fact, there are infinitely many real numbers that are represented by one IEEE 754 number.

When representing a real number, the IEEE 754 standard defines which IEEE 754 number shall be chosen to represent it. The default method specified by IEEE 754 is as follows:

"Round to nearest, ties to even" – round the real number to the nearest IEEE 754 value; if the real number falls midway it is rounded to the nearest value with an even (zero) least significant bit.

This is the algorithm used by the Rebol LOAD function. This way, infinitely many real numbers will be rounded to the same IEEE 754 value. The rounding accuracy (it is also the accuracy of the Rebol LOAD function) is known to be 15.95 decimal digits meaning that the obtained IEEE 754 number has sometimes 15 (or less) but most of the time 16 decimal digits equal to the digits of the real number it represents.

That does not mean IEEE 754 never represents real numbers exactly. For example, 1.0 is in the set of IEEE 754 numbers, meaning that it can be represented exactly.

As noted above the relation between real numbers and IEEE 754 numbers is not symmetric. Therefore, we also need to determine which "representant" shall be chosen to represent a given IEEE 754 number (a Rebol decimal). This is what essentially happens when Rebol decimals are formed to strings. There actually are infinitely many real numbers that can serve for the purpose, but the MOLD function is expected to choose just one.

Based on the informations from the previous section the R2 interpreter tried to solve the issue by molding Rebol decimal! values using 15 decimal digits of precision. The problem was that 15 decimal digits of precision did not suffice (in general) to represent a given 64-bit IEEE 754 binary floating point number. For example:

>> mold 1.7976931348623157e308 == "1.79769313486232E+308"

, while:

>> load mold 1.7976931348623157e308 ** Math Error: Math or number overflow ** Near: load mold 1.79769313486232E+308

demonstrates that 15 digits don't suffice for the purpose of representing the above number. Therefore, the question is which representation is sufficient. The criterium can be even defined as a Rebol function:

precise-enough?: func [

"Does the given STRING represent the given decimal! VALUE precisely enough?"

string [string!]

value [decimal!]

] [

found? attempt [

all [

zero? subtract load string value

same? load string value

]

]

]

, which yields

precise-enough? "1.79769313486232e308" 1.7976931348623157e308 ; == false

This case can be used also to demonstrate that even 16 digits of precision do not suffice for the purpose of representing the given IEEE 754 number:

precise-enough? "1.797693134862316e308" 1.7976931348623157e308 ; == false

On the other hand it is known that 17 decimal digits of precision are sufficient for every 64-bit IEEE 754 binary floating point number.

In R3, the number of digits to be used in forming/molding decimal numbers is specified by:

system/options/decimal-digits

It defaults to 15 digits.

The forming precision can be set higher and for MOLD/ALL the precision used is 17 decimal digits, i.e., the precision known to be always sufficient.

However, for some cases much shorter representations are sufficient as well.

Example: due to the fact that the format is binary, it cannot exactly represent all decimal fractions. For example, there is no "exact 0.1" in the set of IEEE 754 binary floating point numbers. When using the "round to the nearest" approach the nearest IEEE 754 number to 0.1 is 0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625 . Fortunately enough, it is not necessary to remember or handle such a long string of decimal digits since the "0.1" string is already sufficient to represent it as the reader might expect:

precise-enough? "0.1" 0.1 ; == true

This example suggests that it makes sense for MOLD/ALL (or even MOLD, if we decide) to yield the shortest string that represents the given decimal! value precisely enough.

Comparing Rebol decimal numbers is somewhat complicated. The reason for this is that Rebol decimals are based on the IEEE 754 floating point standard which has a limited number of digits. This can lead to very slight errors during computations, and those errors can also accumulate when multiple computations are performed on the results.

There are two primary ways to check for zero:

zero? number number = 0

The second has a few variations, which are described below in the comparison section.

Decimal values support these equality comparison functions:

- same? - Returns TRUE if the values are identical.

- strict-equal? - Returns TRUE if the values are equal and of the same datatype.

- strict-not-equal? - Returns TRUE if the values are not equal and/or not of the same datatype.

- equal? - Returns TRUE if the values are nearly equal.

- not-equal? - Returns TRUE if the values are not nearly equal.

- greater? - Returns TRUE if the first value is greater than the second value.

- lesser? - Returns TRUE if the first value is less than the second value.

- greater-or-equal? - Returns TRUE if the first value is greater than or equal to the second value.

- lesser-or-equal? - Returns TRUE if the first value is less than or equal to the second value.

- minimum - Returns the lesser of the two values.

- maximum - Returns the greater of the two values.

The above functions are also available as infix operators:

- =? - same

- = - equal

- <> - not equal

- == - strict-equal

- > - greater

- >= - greater or equal

- < - lesser (less than)

- <= - lesser or equal

The precision issues related to decimal (floating point) numbers mentioned above can make comparing decimal values problematic in many cases.

The example below shows what you would expect as the result:

>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 == 0.3

However, if you examine it a little closer, you will find:

>> system/options/decimal-digits: 17 >> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 == 0.30000000000000004

Thus, adding 0.1 three times is not strictly equal to 0.3!

To make it a bit easier on users (especially those of us who do not want to be experts in floating point math errors), the equality comparison function has been changed to account for "nearness" in such cases.

For example:

>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 = 0.3 == true

That seems useful, but we know from the above that the values internally are not strictly equal:

>> 0.1 + 0.1 + 0.1 == 0.3 == false

If you need to know more, please see the notes below for more information.

There are three levels of equality strictness. They are:

- sameness - the decimal numbers must be identical, that is the internal binary representations must match perfectly.

- strictly equal - as above, just the "negative zero" is considered strictly equal to "positive zero".

- nearly equal - the decimal numbers must be nearly equal. This is measured by a comparison algorithm that accounts for minor variations at near (but not exactly) the epsilon precision. For more details see the "Comparing using integers" section in the Comparing floating point numbers article.

- sameness: same? (=?)

- strictly equal: strict-equal? (==) and strict-not-equal? (!=)

- nearly equal: equal? (=) and not-equal? (<>)

The ROUND function rounds a given decimal value N to a multiple of a given (or implied) SCALE value. In case the SCALE value is not given, it is deemed to be equal to 1.0, i.e. the rounding to an integral value occurs.

This method of rounding is the most flexible one allowing us to round to a multiple of essentially any SCALE value.

Due to the fact, that some usual values like 0.1 or 0.01 are not exactly representable using the 64-bit IEEE754 binary floating point format, rounding to multiples of such values can be only approximate, no matter what method is used.